A Survey of the Nutrient Content of Foods Consumed by Free Ranging and Captive Anegada Iguanas (Cyclura Pinguis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

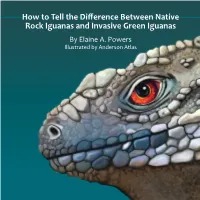

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

ISG News 5(1)

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 7 • Number 1 • Spring 2004 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and E awareness programs that help nternational Iguana Foundation Announces 2004 Grants The Board ensure the survival of wild Iof Directors of the International Iguana Foundation (IIF) held their annual iguanas and their habitats. meeting at the Miami Metrozoo in Florida on 3 April 2004. The Board evalu- ated a total of seven proposals and awarded grants totaling $48,550 for the following five projects: 1) Establishing a second subpopulation of released Grand Cayman blue iguanas, Cyclura lewisi. Fred Burton, Blue Iguana Recovery Program. $11,000. 2) Conservation of the critically endangered Jamaican iguana, Cyclura collei. Peter IN THIS ISSUE Vogel and Byron Wilson, Jamaican Iguana Research and Conservation Group. News & Comments ............... 1 $11,300. Taxon Reports ...................... 4 3) Maintaining and optimizing the headstart release program for the Anegada Iguana iguana ................... 4 Island iguana, Cyclura pinguis. Glenn Gerber (San Diego Zoo) and Kelly Bra- Cyclura nubila nubila ......... 7 dley (Dallas Zoo and University of Texas). $11,250. Cyclura pinguis ............... 12 4) Translocation, population surveys, and habitat restoration for the Bahamian Recent Literature ................ 14 iguanas, Cyclura r. rileyi and Cyclura r. cristata. William Hayes, Loma Linda ISG contact information ....... 14 University. $7,500. 5) Conservation biology and management of the Saint Lucian iguana, Iguana iguana. Matt Morton (Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust) and Karen Gra- ham (Sedgwick County Zoo). $7,500. Rick Hudson, IIF Program Officer Fort Worth Zoo [email protected] bituary E The herpetology and veterinary ayman Brac Land Preservation E The 2 Ostaff of the Gladys Porter Zoo sadly report the CInternational Reptile Conservation Foundation passing of the longest living member of the genus Cy- (IRCF), a 501 c(3) non-profit corporation directed by clura on record. -

Cyclura Cychlura) in the Exuma Islands, with a Dietary Review of Rock Iguanas (Genus Cyclura)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):121–138. Submitted: 15 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. FOOD HABITS OF NORTHERN BAHAMIAN ROCK IGUANAS (CYCLURA CYCHLURA) IN THE EXUMA ISLANDS, WITH A DIETARY REVIEW OF ROCK IGUANAS (GENUS CYCLURA) KIRSTEN N. HINES 3109 Grand Ave #619, Coconut Grove, Florida 33133, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—This study examined the natural diet of Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) in the Exuma Islands. The diet of Cyclura cychlura in the Exumas, based on fecal samples (scat), encompassed 74 food items, mainly plants but also animal matter, algae, soil, and rocks. This diet can be characterized overall as diverse. However, within this otherwise broad diet, only nine plant species occurred in more than 5% of the samples, indicating that the iguanas concentrate feeding on a relatively narrow core diet. These nine core foods were widely represented in the samples across years, seasons, and islands. A greater variety of plants were consumed in the dry season than in the wet season. There were significant differences in parts of plants eaten in dry season versus wet season for six of the nine core plants. Animal matter occurred in nearly 7% of samples. Supported by observations of active hunting, this result suggests that consumption of animal matter may be more important than previously appreciated. A synthesis of published information on food habits suggests that these results apply generally to all extant Cyclura species, although differing in composition of core and overall diets. Key Words.—Bahamas; Caribbean; carnivory; diet; herbivory; predation; West Indian Rock Iguanas INTRODUCTION versus food eaten in unaffected areas on the same island, finding differences in both diet and behavior (Hines Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) 2011). -

Nesting Migrations and Reproductive Biology of the Mona Rhinoceros Iguana, Cyclura Stejnegeri

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):197–213. Submitted: 2 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. NESTING MIGRATIONS AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF THE MONA RHINOCEROS IGUANA, CYCLURA STEJNEGERI 1,3 1 2 NÉSTOR PÉREZ-BUITRAGO , ALBERTO M. SABAT , AND W. OWEN MCMILLAN 1Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico – Río Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092 Panamá, República of Panamá 3 Current Address: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Orinoquía, Grupo de Investigación en Ciencias de la Orinoquía (GICO), km 9 vía Tame, Arauca, Colombia 3Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—We studied the nesting migrations and reproductive ecology of the endangered Mona Rhinoceros Iguana Cyclura stejnegeri at three localities from 2003 to 2006. Female movements while seeking a nesting site ranged from 0.3 to 12.8 km, were mostly erratic. Time elapsed between mating and oviposition averaged 30 ± 5 days, while the nesting period lasted four weeks (July to early August). Nest site fidelity by females in consecutive years was 50%, although non-resident females at one study site used the same beach 72% of the time. Clutch size averaged 14 eggs and was positively correlated with female snout-vent length (SVL). Egg length was the only egg size variable correlated negatively with female size. Incubation temperatures averaged 32.8° C (2005) and 30.2° C (2006) and fluctuated up to 9° C. Overall hatching success from 2003–2005 was 75.9%. Some nests failed as a result of flooding of the nest chamber and in one case a nest was destroyed by feral pigs. -

Behavior and Ecology of the Rock Iguana Cyclura Carinata

BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF THE ROCK IGUANA CYCLURA CARINATA By JOHN BURTON IVERSON I I 1 A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1977 Dedicat ion To the peoples of the Turks and Caicos Islands, for thefr assistances in making this study possible, with the hope that they might better see the uniqueness of their iguana and deem it worthy of protection. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS express my sincere gratitude to V/alter Auffenberg, I vjish to chairman of my doctoral committee, for his constant aid and encourage- ment during this study. Thanks also are due to the other members of my committee: John Kaufmann, Frank Nordlie, Carter Gilbert, and Wi 1 lard Payne. 1 am particularly grateful to the New York Zoological Society for providing funds for the field work. Without its support the study v;ould have been infeasible. Acknowledgment is also given to the University of Florida and the Florida State Museum for support and space for the duration of my studies. Of the many people in the Caicos Islands who made this study possible, special recognition is due C. W. (Liam) Maguire and Bill and Ginny Cowles of the Meridian Club, Pine Cay, for their generosity in providing housing, innumerable meals, access to invaluable maps, and many other courtesies during the study period. Special thanks are also due Francoise de Rouvray for breaking my monotonous bean, raisin, peanut butter, and cracker diet with incompar- able French cuisine, and to Gaston Decker for extending every kindness to me v;hile cj Pine Cay. -

Cyclura Rileyi Rileyi) in the Bahamas

LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Graduate School _________________ Behavioral Ecology of the Endangered San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi rileyi) in the Bahamas by Samuel Cyril, Jr. _________________ A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology _________________ June 2001 i Note: This thesis has been formatted for Adobe Acrobat publication and may not match the original thesis © 2001 Samuel Cyril, Jr. All Rights Reserved ii Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in his opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree Master of Science. ___________________________________________,Chairman William K. Hayes, Associate Professor of Biology ___________________________________________________ Ronald L. Carter, Chair and Professor of Biology ___________________________________________________ David Cowles, Associate Professor of Biology iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful for all the many individuals who assisted me in many ways for the success of this project. My mother, Lucienne Cyril, was there pushing for me to do my best and to keep focused. The presence of my son, Lucas Amano-Cyril, encouraged me to push forward. While in the field collecting data, a long time friend, Eric Chung, helped me immensely in setting up and planning my research. Eric’s input, hard work, and support proved to be crucial in helping me to collect the data needed for my research. Denise Heller and Johnathan Rivera dedicated a portion of their time to helping me collect data, which would have proved difficult without their help. My colleague, Roland Sosa, pushed me and encouraged me to succeed. Dr. William Hayes challenged my thoughts, views, and ideas into constructing the best experience I’ve ever had. -

The Nesting Ecology of the Allen Cays Rock Iguana, Cyclura Cychlura Inornata in the Bahamas

Herpetological Monographs, 18, 2004, 1–36 Ó 2004 by The Herpetologists’ League, Inc. THE NESTING ECOLOGY OF THE ALLEN CAYS ROCK IGUANA, CYCLURA CYCHLURA INORNATA IN THE BAHAMAS 1,4 2 3 JOHN B. IVERSON ,KIRSTEN N. HINES , AND JENNIFER M. VALIULIS 1Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, IN 47374, USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, University Park, Miami, FL 33199, USA 3Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Ft. Collins, CO 80523, USA ABSTRACT: The nesting ecology of the Allen Cays rock iguana was studied on Leaf Cay and Southwest Allen’s Cay (5 U Cay) in the northern Exuma Islands, Bahamas, during 2001 and 2002. Mating occured in mid-May, and females migrated 30–173 m to potential nest sites in mid to late June. Females often abandoned initial attempts at digging nest burrows, and average time from initiation of the final burrow to completion of a covered nest was six days. At least some females completely buried themselves within the burrow during the final stages of burrow construction and oviposition. Females defended the burrow site during the entire time of construction, and most continued that defense for at least three to four weeks after nest completion. Nests were completed between mid-June and mid-July, but for unknown reasons timing was seven days earlier on U Cay than on Leaf Cay. Nest burrows averaged 149 cm in length and terminal nest chambers usually angled off the main burrow. Depth to the bottom of the egg chamber averaged 28 cm, and was inversely correlated with shadiness of the site, suggesting that females may select depths with preferred temperatures (mean, 31.4 C in this study). -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL & AMPHIBIANS15, NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 28(2):189 213–217 • AUG 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FromFEATURE ARTICLES Pets to Threats: Invasive Iguanas . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: and OtherOn the Road to Understanding Species the Ecology and Conservation Cause of the Midwest’s SignificantGiant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer Harm 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................to Native Iguanas Robert W. Henderson 198 RESEARCH ARTICLES Gad. The TexasPerry Horned1, Charles Lizard inR. Central Knapp and2,3 Western, Tandora Texas ....................... D. Grant Emily3,4, Stesha Henry, Jason A. PasachnikBrewer, Krista 3,5Mougey,, and and Ioana Gad Perry Coman 204 6 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida 1 Department of Natural ............................................. Resource Management,Brian J. Texas Camposano, Tech KennethUniversity, L. Krysko, Lubbock, Kevin M.Texas Enge, 79409, Ellen M. USA Donlan, ([email protected] and Michael Granatosky [corresponding 212 author]). 2Daniel P. Haerther Center for Conservation and Research, John G. Shedd Aquarium, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT3IUCN SSC Iguana Specialist -

Iguana 12.2 B&W Text

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2005 ONSERVATION AUANATURAL ISTORY AND USBANDRY OF EPTILES IC G, N H , H R International Reptile Conservation Foundation www.IRCF.org GLENN MITCHELL Anegada or Stout Iguana (Cyclura pinguis) (see article on p. 78). JOHN BINNS RICHARD SAJDAK A subadult Stout Iguana (Cyclura pinguis) awaiting release at the head- Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) reach the northernmost extent starting facility on Anegada (see article on p. 78). of their range on the bluff prairies in Wisconsin (see article on p. 90). This cross-stitch was created by Anne Fraser of Calgary, Alberta from a photograph of Carley, a Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi) at the Captive Breeding Facility on Grand Cayman. The piece, which measures 6.8 x 4.2 inches, uses 6,100 stitches in 52 colors and took 180 hours to complete. It will be auctioned by the IRCF at the Daytona International Reptile Breeder’s Expo on 20 August 2005. Profits from the auction will benefit conser- vation projects for West Indian Rock Iguanas in the genus Cyclura. ROBERT POWELL ROBERT POWELL Red-bellied or Black Racers (Alsophis rufiventris) remain abundant on Spiny-tailed Iguanas (Ctenosaura similis) are abundant in archaeologi- mongoose-free Saba and St. Eustatius, but have been extirpated on St. cal zones on the Yucatán Peninsula. This individual is on the wall Christopher and Nevis (see article on p. 62). around the Mayan city of Tulúm (see article on p. 112). TABLE OF CONTENTS IGUANA • VOLUME 12, NUMBER 2 • JUNE 2005 61 IRCFInternational Reptile Conservation Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH ARTICLES Conservation Status of Lesser Antillean Reptiles . -

Spatial Ecology of the Endangered Iguana, Cyclura Lewisi, in A

402 L. KUHNZ ET AL. MILLER,C.M.1944.Ecologicalrelationshipsand STEBBINS, R. C. 1954. Amphibians and Reptiles of adaptations of the limbless lizards of the genus Western North America. McGraw-Hill Inc., New Anniella. Ecological Monographs 14:271–289. York. POWELL, J. A. 1978. Endangered habitats for insects: SZARO, R. C., S. C. BELFIT,K.J.AITKIN, AND R. D. BABB. California coastal sand dunes. Atala 6:41–50. 1988. The use of timed fixed-area plots and a mark- REIN, F. A. 1999. Vegetation Buffer Strips in a Mediter- recapture technique in assessing riparian garter ranean Climate: Potential for Protecting Soil and snake populations. In Proceedings of the Sympo- Water Resources. Unpubl. Ph.D. diss., Univ. of sium on Management of Amphibians, Reptiles, and California, Santa Cruz. Small Mammals in North America, pp. 239–246. SLATTERY, P. N., K. L. USCHYK, AND R. B. BURTON. 2003. U.S. Department of Agriculture General Technical Controlling weeds with weeds: disturbance, suc- Report RM-166, Washington, DC. cession, yellow lupines and their role in the R. L. TASSAN,K.S.HAGEN, AND D. V. CASSIDY. 1982. successful restoration of a native dune communi- Imported natural enemies established against ice- ty. In C. Piosko (ed.), Proceedings of the California plant scales in California. California Agriculture Invasive Plant Council Symposium. Vol. 7, p. 115. September–October. 36:16–17. California Invasive Plant Council, Berkeley. ZAR, J. H. 1984. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice Hall, SLOBODCHIKOFF, C. N., AND J. T. DOYEN. 1977. Effects of Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Ammophila arenaria on sand dune arthropod com- munities. Ecology 58:1171–1175. -

Cyclura Pinguis) Is a Critically Endangered Species Endemic to the Puerto Rico Bank and Currently Restrictedprofile to the British Virgin Islands (BVI)

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS IRCF REPTILES • VOL15, & N AMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 189• 20(3):112–118 • SEP 2013 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Vertical. Chasing Bullsnakes structure (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: use by the Stout Iguana On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: (CycluraA Hypothetical Excursion pinguis ............................................................................................................................) on Guana Island,Robert W. Henderson BVI198 RESEARCH ARTICLES Christopher. TheA. TexasCheek Horned1, Shay Lizard Hlavatyin Central and1, KristaWestern TexasMougey .......................1, Rebecca Emily Henry, N. Perkins Jason Brewer,1, MarkKrista Mougey, A. Peyton and Gad 1Perry, Caitlin 204 N. Ryan2, . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestrisJennifer) in Florida C. Zavaleta 1, Clint W. Boal3, and Gad Perry1 .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1Department of Natural Resources Management, Box 42125, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409 2The Institute of EnvironmentalCONSERVATION and Human ALERT Health, Department of Environmental Toxicology, Box 41163, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409 3U.S.