Iguana 12.2 B&W Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biogeography of the Caribbean Cyrtognatha Spiders Klemen Čandek1,6,7, Ingi Agnarsson2,4, Greta J

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Biogeography of the Caribbean Cyrtognatha spiders Klemen Čandek1,6,7, Ingi Agnarsson2,4, Greta J. Binford3 & Matjaž Kuntner 1,4,5,6 Island systems provide excellent arenas to test evolutionary hypotheses pertaining to gene fow and Received: 23 July 2018 diversifcation of dispersal-limited organisms. Here we focus on an orbweaver spider genus Cyrtognatha Accepted: 1 November 2018 (Tetragnathidae) from the Caribbean, with the aims to reconstruct its evolutionary history, examine Published: xx xx xxxx its biogeographic history in the archipelago, and to estimate the timing and route of Caribbean colonization. Specifcally, we test if Cyrtognatha biogeographic history is consistent with an ancient vicariant scenario (the GAARlandia landbridge hypothesis) or overwater dispersal. We reconstructed a species level phylogeny based on one mitochondrial (COI) and one nuclear (28S) marker. We then used this topology to constrain a time-calibrated mtDNA phylogeny, for subsequent biogeographical analyses in BioGeoBEARS of over 100 originally sampled Cyrtognatha individuals, using models with and without a founder event parameter. Our results suggest a radiation of Caribbean Cyrtognatha, containing 11 to 14 species that are exclusively single island endemics. Although biogeographic reconstructions cannot refute a vicariant origin of the Caribbean clade, possibly an artifact of sparse outgroup availability, they indicate timing of colonization that is much too recent for GAARlandia to have played a role. Instead, an overwater colonization to the Caribbean in mid-Miocene better explains the data. From Hispaniola, Cyrtognatha subsequently dispersed to, and diversifed on, the other islands of the Greater, and Lesser Antilles. Within the constraints of our island system and data, a model that omits the founder event parameter from biogeographic analysis is less suitable than the equivalent model with a founder event. -

Phylogenetic Diversity, Habitat Loss and Conservation in South

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2014) 20, 1108–1119 BIODIVERSITY Phylogenetic diversity, habitat loss and RESEARCH conservation in South American pitvipers (Crotalinae: Bothrops and Bothrocophias) Jessica Fenker1, Leonardo G. Tedeschi1, Robert Alexander Pyron2 and Cristiano de C. Nogueira1*,† 1Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de ABSTRACT Brasılia, 70910-9004 Brasılia, Distrito Aim To analyze impacts of habitat loss on evolutionary diversity and to test Federal, Brazil, 2Department of Biological widely used biodiversity metrics as surrogates for phylogenetic diversity, we Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G. St. NW, Washington, DC 20052, study spatial and taxonomic patterns of phylogenetic diversity in a wide-rang- USA ing endemic Neotropical snake lineage. Location South America and the Antilles. Methods We updated distribution maps for 41 taxa, using species distribution A Journal of Conservation Biogeography models and a revised presence-records database. We estimated evolutionary dis- tinctiveness (ED) for each taxon using recent molecular and morphological phylogenies and weighted these values with two measures of extinction risk: percentages of habitat loss and IUCN threat status. We mapped phylogenetic diversity and richness levels and compared phylogenetic distances in pitviper subsets selected via endemism, richness, threat, habitat loss, biome type and the presence in biodiversity hotspots to values obtained in randomized assemblages. Results Evolutionary distinctiveness differed according to the phylogeny used, and conservation assessment ranks varied according to the chosen proxy of extinction risk. Two of the three main areas of high phylogenetic diversity were coincident with areas of high species richness. A third area was identified only by one phylogeny and was not a richness hotspot. Faunal assemblages identified by level of endemism, habitat loss, biome type or the presence in biodiversity hotspots captured phylogenetic diversity levels no better than random assem- blages. -

(2007) a Photographic Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians Of

A Photographic Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Dominica, West Indies Kristen Alexander Texas A&M University Dominica Study Abroad 2007 Dr. James Woolley Dr. Robert Wharton Abstract: A photographic reference is provided to the 21 reptiles and 4 amphibians reported from the island of Dominica. Descriptions and distribution data are provided for each species observed during this study. For those species that were not captured, a brief description compiled from various sources is included. Introduction: The island of Dominica is located in the Lesser Antilles and is one of the largest Eastern Caribbean islands at 45 km long and 16 km at its widest point (Malhotra and Thorpe, 1999). It is very mountainous which results in extremely varied distribution of habitats on the island ranging from elfin forest in the highest elevations, to rainforest in the mountains, to dry forest near the coast. The greatest density of reptiles is known to occur in these dry coastal areas (Evans and James, 1997). Dominica is home to 4 amphibian species and 21 (previously 20) reptile species. Five of these are endemic to the Lesser Antilles and 4 are endemic to the island of Dominica itself (Evans and James, 1997). The addition of Anolis cristatellus to species lists of Dominica has made many guides and species lists outdated. Evans and James (1997) provides a brief description of many of the species and their habitats, but this booklet is inadequate for easy, accurate identification. Previous student projects have documented the reptiles and amphibians of Dominica (Quick, 2001), but there is no good source for students to refer to for identification of these species. -

Third-Generation Antivenomics Analysis of the Preclinical Efficacy Of

Toxicon: X 1 (2019) 100004 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon: X journal homepage: www.journals.elsevier.com/toxicon-x Third-generation antivenomics analysis of the preclinical efficacy of ® T Bothrofav antivenom towards Bothrops lanceolatus venom ∗ Davinia Plaa, Yania Rodrígueza, Dabor Resiereb, Hossein Mehdaouib, José María Gutiérrezc, , ∗∗ Juan J. Calvetea, a Laboratorio de Venómica Evolutiva y Traslacional, Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia, CSIC, Jaime Roig 11, 46010 Valencia, Spain b Service des Urgences et de Reanimation Polyvalente, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Fort-de-France, Martinique, France c Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Facultad de Microbiología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT ® Keywords: Bothrops lanceolatus inflicts severe envenomings in the Lesser Caribbean island of Martinique. Bothrofav , a Bothrops lanceolatus monospecific antivenom against B. lanceolatus venom, has proven highly effective at the preclinical and clinical ® Antivenom levels. Here, we report a detailed third-generation antivenomics quantitative analysis of Bothrofav . With the Snake venom ® ® exception of poorly-immunogenic peptides, Bothrofav immunocaptured all the major protein components. Bothrofav These results, along with previous preclinical and clinical observations, underscore the high neutralizing efficacy Third-generation antivenomics of the antivenom against B. lanceolatus venom. Martinique Bothrops lanceolatus is an endemic viperid snake in the French and therapeutic antibody molecules present in an antivenom. Thus, overseas Department of Martinique, in the Lesser Caribbean, where it neutralization assays and antivenomics complement each other in the represents the only venomous snake (Campbell and Lamar, 2004). En- characterization of the preclinical efficacy of antivenoms (Gutiérrez venomings by this species are similar to those inflicted by other Bo- et al., 2017). -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

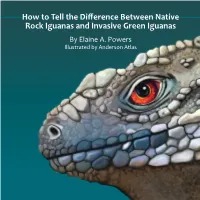

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Different Environmental Gradients Affect Different Measures of Snake Β-Diversity in the Amazon Rainforests

Different environmental gradients affect different measures of snake β-diversity in the Amazon rainforests Rafael de Fraga1,2,3, Miquéias Ferrão1, Adam J. Stow2, William E. Magnusson4 and Albertina P. Lima4 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia 3 Programa de Pós-graduação em Sociedade, Natureza e Desenvolvimento, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, Brazil 4 Coordenação de Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil ABSTRACT Mechanisms generating and maintaining biodiversity at regional scales may be evaluated by quantifying β-diversity along environmental gradients. Differences in assemblages result in biotic complementarities and redundancies among sites, which may be quantified through multi-dimensional approaches incorporating taxonomic β-diversity (TBD), functional β-diversity (FBD) and phylogenetic β-diversity (PBD). Here we test the hypothesis that snake TBD, FBD and PBD are influenced by environmental gradients, independently of geographic distance. The gradients tested are expected to affect snake assemblages indirectly, such as clay content in the soil determining primary production and height above the nearest drainage determining prey availability, or directly, such as percentage of tree cover determining availability of resting and nesting sites, and climate (temperature and precipitation) causing physiological filtering. We sampled snakes in 21 sampling plots, each covering five km2, distributed over 880 km in the central-southern Amazon Basin. We used dissimilarities between sampling sites to quantify TBD, FBD and PBD, Submitted 30 April 2018 which were response variables in multiple-linear-regression and redundancy analysis Accepted 23 August 2018 Published 24 September 2018 models. -

Iguana Iguana

Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil To cite this version: Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil. Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2015, 10 (6), 10.1371/journal.pone.0127575. hal-01901355 HAL Id: hal-01901355 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01901355 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic Evidence of Hybridization between the Endangered Native Species Iguana delicatissima and the Invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

First Report of Cannibalism in The

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & IRCFAMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL 15,& NAMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 •189 21(4):136–137 • DEC 2014 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES First. Chasing Bullsnakes Report (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin:of Cannibalism in the On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: Saba AnoleA Hypothetical Excursion ( ............................................................................................................................Anolis sabanus), withRobert W. Hendersona Review 198 ofRESEARCH Cannibalism ARTICLES in West Indian Anoles . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida 1 2 .............................................Brian J. RobertCamposano, Powell Kenneth L. andKrysko, Adam Kevin M. Watkins Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1Department of Biology, Avila University, Kansas City, Missouri 64145, USA ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT 2Chizzilala Video Productions, Saba ([email protected]) . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica.