ISG News 5(1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums

Reciprocity Please Note: Due to COVID-19, organizations on this list may have put their reciprocity program on hold as advance reservations are now required for many parks. We strongly recommend that you call the zoo or aquarium you are visiting in advance of your visit. Thank you for your patience and understanding during these unprecedented times. Wilds Members: Members of The Wilds receive DISCOUNTED or FREE admission to the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. Wilds members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains its own discount policies, and The Wilds strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. Each zoo reserves the right to limit the amount of discounts, and may not offer discounted tickets for your entire family size. *This list is subject to change at any time. Visiting The Wilds from Other Zoos: The Wilds is proud to offer a 50% discount on the Open-Air Safari tour to members of the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. The reciprocal discount does not include parking. If you do not have a valid membership card, please contact your zoo’s membership office for a replacement. This offer cannot be combined with any other offers or discounts, and is subject to change at any time. Park capacity is limited. Due to COVID-19 advance reservations are now required. You may make a reservation by calling (740) 638-5030. You must present your valid membership card along with your photo ID when you check in for your tour. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

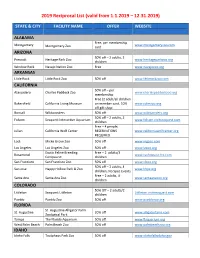

Reciprocal Zoo List 2019 for Website

2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) STATE & CITY FACILITY NAME OFFER WEBSITE ALABAMA Free, per membership Montgomery www.montgomeryzoo.com Montgomery Zoo card ARIZONA 50% off – 2 adults, 3 Prescott Heritage Park Zoo www.heritageparkzoo.org children Window Rock Navajo Nation Zoo Free www.navajozoo.org ARKANSAS Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% off www.littlerockzoo.com CALIFORNIA 50% off – per Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo www.charlespaddockzoo.org membership Free (2 adult/all children Bakersfield California Living Museum on member card, 10% www.calmzoo.org off gift shop Bonsall Wildwonders 50% off www.wildwonders.org 50% off – 2 adults, 2 Folsom Seaquest Interactive Aquarium www.folsom.visitseaquest.com children Free – 4 people; Julian California Wolf Center RESERVATIONS www.californiawolfcenter.org REQUIRED Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% off www.mgzoo.com Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% off www.lazoo.org Exotic Feline Breeding Free – 2 adults/3 Rosamond www.cathopuise.fcc.com Compound children San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% off www.sfzoo.org 50% off – 2 adults, 4 San Jose Happy Hollow Park & Zoo www.hhpz.org children, No Spec Events Free – 2 adults, 4 Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo www.santaanazoo.org children COLORADO 50% Off – 2 adults/2 Littleton Seaquest Littleton Littleton.visitseaquest.com children Pueblo Pueblo Zoo 50% off www.pueblozoo.org FLORIDA St. Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine 20% off www.alligatorfarm.com Zoological Park Tampa The Florida Aquarium 50% off www.flaquarium.org West Palm Beach Palm Beach Zoo 50% off www.palmbeachzoo.org IDAHO Idaho Falls Tautphaus Park Zoo 50% off www.idahofallsidaho.gov 2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) Free – 2 adults, 5 Pocatello Pocatello Zoo www.zoo.pocatello.us children ILLINOIS Free – 2 adults, 3 Springfield Henson Robinson Zoo children. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

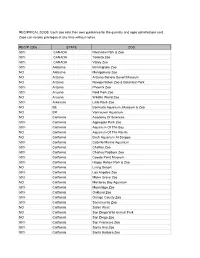

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

RECIPROCAL LIST from YOUR ORGANIZATION and CALL N (309) 681-3500 US at (309) 681-3500 to CONFIRM

RECIPROCAL LOCAL HIGHLIGHTS RULES & POLICIES Enjoy a day or weekend trip Here are some important rules and to these local reciprocal zoos: policies regarding reciprocal visits: • FREE means free general admission and 50% off means 50% off general Less than 2 Hours Away: admission rates. Reciprocity applies to A Peoria Park District Facility the main facility during normal operating Miller Park Zoo, Bloomington, IL: days and hours. May exclude special Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. exhibits or events requiring extra fees. RECIPROCAL Niabi Zoo, Coal Valley, IL: • A membership card & photo ID are Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. always required for each cardholder. LIST Scovill Zoo, Decatur, IL: • If you forgot your membership card Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. at home, please call the Membership Office at (309) 681-3500. Please do this a few days in advance of your visit. More than 2 Hours Away: • The number of visitors admitted as part of a Membership may vary depending St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO: on the policies and level benefits of Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general the zoo or aquarium visited. (Example, admission and 50% off Adventure Passes. some institutions may limit number of children, or do not allow “Plus” guests.) Milwaukee Zoo, Milwaukee, WI: Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. • This list may change at anytime. Please call each individual zoo or aquarium Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL: BEFORE you visit to confirm details and Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general restrictions! admission and 10% off retail and concessions. DUE TO COVID-19, SOME FACILITIES Cosley Zoo, Wheaton, IL: MAY NOT BE PARTICIPATING. -

Birds in Texas Zoos

Birds in Texas Zoos by Josef Lindholm, III {tailor's Note: This wticle was writ/en to Brotogeris, Keeper/Birds Grey-cheeked White-hel open up a whole new world for those of us Fort Worth Zoological Park lied Caique, and White-crowned Parrot wbo love bin/s, love zoos and love to vacation. (Pionus senilis) . To somefolks, '"Texas" conjures up annadil/os, dust and cowboys-or oil barollS and villiam Inside the heautiful Hixon Tropical ofthe old 7Vprogram ·'Dallas." 77Jere may be Bird House can be found the last some truth to these images buttbere is a great the eight crane taxa, which also White-necked Picathartes in the deal more-pwticularly for bird lovers- as include one of the few proven hreed Western Hemisphere (hatched at San thefollOWing article explains. Readandenjoy. See you in San Antonio. SID} ing pairs of Hooded Cranes in captivi Antonio), the first Woodland ty. Kingfishers (Halcyon senegalensis) to Most zoos today display far fewer breed in an American Zoo, Golden s of 1 January 1996, of the 25 pan'ot species than they used to and it headed Quetzals, hreeding Cinnamon largest U.S. zoo bird collec is rare to find more than a dozen or so Warhling Finches (Poospiza ornata), A tions (by species) listed by the taxa on display. San Antonio, howev Long-tailed and Lesser Green American Zoo and Aquarium er, holds more than 40 species. While Broadhills. Golden-headed Manakins, Association (996), five were Texan. it is, of course, exciting to see such rar Chinese Bamhoo Partridges and many Two of these. -

Cyclura Cychlura) in the Exuma Islands, with a Dietary Review of Rock Iguanas (Genus Cyclura)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):121–138. Submitted: 15 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. FOOD HABITS OF NORTHERN BAHAMIAN ROCK IGUANAS (CYCLURA CYCHLURA) IN THE EXUMA ISLANDS, WITH A DIETARY REVIEW OF ROCK IGUANAS (GENUS CYCLURA) KIRSTEN N. HINES 3109 Grand Ave #619, Coconut Grove, Florida 33133, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—This study examined the natural diet of Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) in the Exuma Islands. The diet of Cyclura cychlura in the Exumas, based on fecal samples (scat), encompassed 74 food items, mainly plants but also animal matter, algae, soil, and rocks. This diet can be characterized overall as diverse. However, within this otherwise broad diet, only nine plant species occurred in more than 5% of the samples, indicating that the iguanas concentrate feeding on a relatively narrow core diet. These nine core foods were widely represented in the samples across years, seasons, and islands. A greater variety of plants were consumed in the dry season than in the wet season. There were significant differences in parts of plants eaten in dry season versus wet season for six of the nine core plants. Animal matter occurred in nearly 7% of samples. Supported by observations of active hunting, this result suggests that consumption of animal matter may be more important than previously appreciated. A synthesis of published information on food habits suggests that these results apply generally to all extant Cyclura species, although differing in composition of core and overall diets. Key Words.—Bahamas; Caribbean; carnivory; diet; herbivory; predation; West Indian Rock Iguanas INTRODUCTION versus food eaten in unaffected areas on the same island, finding differences in both diet and behavior (Hines Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) 2011). -

A Survey of the Nutrient Content of Foods Consumed by Free Ranging and Captive Anegada Iguanas (Cyclura Pinguis)

A SURVEY OF THE NUTRIENT CONTENT OF FOODS CONSUMED BY FREE RANGING AND CAPTIVE ANEGADA IGUANAS (CYCLURA PINGUIS) Ann M. Ward, MS,1* Janet L. Dempsey, MS,, and Amy S. Hunt, MS1 1Nutritional Services Department, Fort Worth Zoo, Fort Worth, Texas; 2Animal Nutrition Department, Saint Louis Zoo, Saint Louis, Missouri Abstract Nutrient concentrations were determined in foods consumed by both free ranging and captive Anegada iguanas (Cyclura pinguis). Twenty-two species of plants, known to be consumed by free ranging iguanas during the dry season, were collected and analyzed. The plant parts were separated and categorized for analysis as flowers, fruits, or leaves. Mean nutrient concentrations and standard errors (SEM), on a dry matter basis (DMB), included protein (CP) 9.61% ± 0.84, acid detergent fiber (ADF) 29.17% ± 2.29, neutral detergent fiber (NDF) 37.48% ± 3.06, and crude fat (FAT) 4.87% ± 0.81. Nutrient concentrations were analyzed in diets offered and consumed by captive iguanas held for re-introduction at a headstart facility on Anegada, British Virgin Islands. Captive diets were comprised of mixed greens (cabbage, romaine), natural leaves (buttonwood and parrotwood), fruits (banana, honeydew melon), vegetables (red pepper, carrot, cucumber, mushroom), and a commercial complete feed (Zoo Med Juvenile Iguana Diet). Diets consumed by hatchlings and juveniles were 17.36 – 21.97% CP, 18.24 – 34.95% ADF, 18.57 – 36.08% NDF, and 2.11 – 4.36% FAT. All captive Anegada iguanas consumed higher protein levels than those levels available in plants during the dry season. These captive consumption levels were similar to those consumed by headstarted Jamaican iguanas (Cyclura collei), as well as levels in plants collected during the dry season in Jamaica. -

Nesting Migrations and Reproductive Biology of the Mona Rhinoceros Iguana, Cyclura Stejnegeri

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):197–213. Submitted: 2 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. NESTING MIGRATIONS AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF THE MONA RHINOCEROS IGUANA, CYCLURA STEJNEGERI 1,3 1 2 NÉSTOR PÉREZ-BUITRAGO , ALBERTO M. SABAT , AND W. OWEN MCMILLAN 1Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico – Río Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092 Panamá, República of Panamá 3 Current Address: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Orinoquía, Grupo de Investigación en Ciencias de la Orinoquía (GICO), km 9 vía Tame, Arauca, Colombia 3Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—We studied the nesting migrations and reproductive ecology of the endangered Mona Rhinoceros Iguana Cyclura stejnegeri at three localities from 2003 to 2006. Female movements while seeking a nesting site ranged from 0.3 to 12.8 km, were mostly erratic. Time elapsed between mating and oviposition averaged 30 ± 5 days, while the nesting period lasted four weeks (July to early August). Nest site fidelity by females in consecutive years was 50%, although non-resident females at one study site used the same beach 72% of the time. Clutch size averaged 14 eggs and was positively correlated with female snout-vent length (SVL). Egg length was the only egg size variable correlated negatively with female size. Incubation temperatures averaged 32.8° C (2005) and 30.2° C (2006) and fluctuated up to 9° C. Overall hatching success from 2003–2005 was 75.9%. Some nests failed as a result of flooding of the nest chamber and in one case a nest was destroyed by feral pigs.