Spatial Ecology of the Endangered Iguana, Cyclura Lewisi, in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

Conocarpus Erectus

Conocarpus erectus (Button Mangrove, Green Buttonwood) Button mangrove is a broadleaf evergreen trees which can withstand drought, salt, heat and high winds.The fruit looks like a dried raspberry or a pine cone. Its flaky brown bark is very attractive. Throughout the year, greenish-white and purple flowers are produced, but they are not noticeable. Due to the high tolerance of heat and drought it is used a lot in hot and arid climate as hedge, street tree or windbreak. Landscape Information French Name: Chêne Guadeloupe ﺩﻣﺲ ﻗﺎﺋﻢ :Arabic Name Pronounciation: kawn-oh-KAR-pus ee-RECK- tus Plant Type: Tree Origin: Florida and the West Indies Heat Zones: 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 Hardiness Zones: 10, 11, 12, 13 Uses: Screen, Hedge, Bonsai, Specimen, Container, Shade, Windbreak, Pollution Tolerant / Urban, Reclamation Size/Shape Growth Rate: Moderate Plant Image Tree Shape: Spreading, Vase Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Medium Canopy Texture: Fine Height at Maturity: 8 to 15 m Spread at Maturity: 8 to 10 meters Conocarpus erectus (Button Mangrove, Green Buttonwood) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Lanceolate Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Glossy, Fine Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Image Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Color: Green, White Seasons: Year Round Trunk Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Generally resists breakage Number of -

Conocarpus Erectus" Plant As Biomonitoring of Soil and Air Pollution in Ahwaz Region

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (10): 1319-1324, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.13.10.1182 Evaluation of "Conocarpus erectus" Plant as Biomonitoring of Soil and Air Pollution in Ahwaz Region 12Ali Gholami, Amir Hossein Davami, 3Ebrahim Panahpour and 4Hossein Amini 1,3Department of Soil Science, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khouzestan, Iran 2Department of Environmental Management, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khouzestan, Iran 4Department of Soil Science, Islamic Azad University, Khorasgan Branch, Isfahan, Iran Abstract: Effects of soil and atmosphere pollution on some heavy metals (Fe, Zn, Pb, Cu, Mn and Cd) concentration in Button-tree (Conocarpus erectus) leaves were studied in the city of Ahwaz (Khouzestan, Iran). Samples were collected from four sampling sites representing area of high traffic density, area future away from traffic and Industrial area. Samples were collected in two stages (May and October) in 2011 for chemical analysis. Samples from village near the city also analyzed for comparison. Based on the results, the stages of leaf sampling did not showed any significant effect on the concentration of the measured heavy metals in leaf samples. Chemical analysis of soil samples at depth of 0-10cm showed that concentration of most of these elements was lower than the maximum recommended levels. Concentrations of measured heavy metals in washed leaves were lower than those of unwashed leaves of Conocarpus and different was significant. In spite of that, there was no significant correlation between the concentrations of heavy metals in washed leaves and soil samples. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

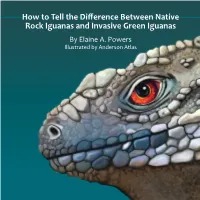

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

ISG News 9(1).Indd

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 9 • Number 1 • Summer 2006 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and onservation Centers for Species Survival Formed j Cyclura spp. were awareness programs that help Cselected as a taxa of mutual concern under a new agreement between a select ensure the survival of wild group of American zoos and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The zoos - under iguanas and their habitats. the banner of Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2) - and USFWS have pledged to work cooperatively to advance conservation of the selected spe- cies by identifying specific research projects, actions, and opportunities that will significantly and clearly support conservation efforts. Cyclura are the only lizards selected under the joint program. The zoos participating in the program include the San Diego Wild Animal Park, Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, The Wilds, White Oak Conservation Center and the National Zoo’s Conservation and Research Center. USFWS participation will be coordinated by Bruce Weissgold in the Division of Management Authority (bruce_weissgold @fws.gov). IN THIS ISSUE News & Comments ............... 1 RCC Facility at Fort Worth j The Fort Worth Zoo recently opened their Animal Outreach and Conservation Center (ARCC) in an off-exhibit Iguanas in the News ............... 3 A area of the zoo. The $1 million facility actually consists of three separate units. Taxon Reports ...................... 7 The primary facility houses the zoo’s outreach collection, while a state-of-the-art B. vitiensis ...................... 7 reptile conservation greenhouse will highlight the zoo’s work with endangered C. pinguis ..................... 9 iguanas and chelonians. -

TAXON:Conocarpus Erectus L. SCORE:5.0 RATING:Evaluate

TAXON: Conocarpus erectus L. SCORE: 5.0 RATING: Evaluate Taxon: Conocarpus erectus L. Family: Combretaceae Common Name(s): button mangrove Synonym(s): Conocarpus acutifolius Willd. ex Schult. buttonwood Conocarpus procumbens L. Sea mulberry Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 30 Jul 2018 WRA Score: 5.0 Designation: EVALUATE Rating: Evaluate Keywords: Tropical Tree, Naturalized, Coastal, Pure Stands, Water-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 n outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans y=1, n=0 n 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 n 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 n Creation Date: 30 Jul 2018 (Conocarpus erectus L.) Page 1 of 17 TAXON: Conocarpus erectus L. -

A Caenorhabditis Elegans Model for Discovery of Novel Anti-Infectives

fmicb-07-01956 November 30, 2016 Time: 12:40 # 1 REVIEW published: 02 December 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01956 Beyond Traditional Antimicrobials: A Caenorhabditis elegans Model for Discovery of Novel Anti-infectives Cin Kong†, Su-Anne Eng, Mei-Perng Lim and Sheila Nathan* School of Biosciences and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia The spread of antibiotic resistance amongst bacterial pathogens has led to an urgent need for new antimicrobial compounds with novel modes of action that minimize the potential for drug resistance. To date, the development of new antimicrobial drugs is still lagging far behind the rising demand, partly owing to the absence of an effective screening platform. Over the last decade, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans Edited by: Luis Cláudio Nascimento Da Silva, has been incorporated as a whole animal screening platform for antimicrobials. This CEUMA University, Brazil development is taking advantage of the vast knowledge on worm physiology and how it Reviewed by: interacts with bacterial and fungal pathogens. In addition to allowing for in vivo selection Osmar Nascimento Silva, of compounds with promising anti-microbial properties, the whole animal C. elegans Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Brazil screening system has also permitted the discovery of novel compounds targeting Francesco Imperi, infection processes that only manifest during the course of pathogen infection of the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy host. Another advantage of using C. elegans in the search for new antimicrobials is that *Correspondence: Sheila Nathan the worm itself is a source of potential antimicrobial effectors which constitute part of its [email protected] immune defense response to thwart infections. -

Roatán Spiny-Tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura Oedirhina) Conservation Action Plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A

Roatán spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura oedirhina) Conservation action plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A. Pasachnik, Ashley B.C. Goode and Tandora D. Grant INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,400 government and NGO members and almost 15,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by around 950 staff in more than 50 countries and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org IUCN Species Programme The IUCN Species Programme supports the activities of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and individual Specialist Groups, as well as implementing global species conservation initiatives. It is an integral part of the IUCN Secretariat and is managed from IUCN’s international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. The Species Programme includes a number of technical units covering Wildlife Trade, the Red List, Freshwater Biodiversity Assessments (all located in Cambridge, UK), and the Global Biodiversity Assessment Initiative (located in Washington DC, USA). IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of more than 9,000 experts. -

Population Structure of the Lower Keys Marsh Rabbit As Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

Management and Conservation Note Population Structure of the Lower Keys Marsh Rabbit as Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Analysis AMANDA L. CROUSE, College of Veterinary Medicine, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4461, USA RODNEY L. HONEYCUTT, Natural Science Division, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA 90263-4321, USA ROBERT A. MCCLEERY,1 Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258, USA CRAIG A. FAULHABER, Department of Wildland Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5230, USA NEIL D. PERRY, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City, UT 84270-0606, USA ROEL R. LOPEZ, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258, USA ABSTRACT We used nucleotide sequence data from a mitochondrial DNA fragment to characterize variation within the endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris hefneri). We observed 5 unique mitochondrial haplotypes across different sampling sites in the Lower Florida Keys, USA. Based on the frequency of these haplotypes at different geographic locations and relationships among haplotypes, we observed 2 distinct clades or groups of sampling sites (western and eastern clades). These 2 groups showed low levels of gene flow. Regardless of their origin, marsh rabbits from the Lower Florida Keys can be separated into 2 genetically distinct management units, which should be considered prior to implementation of translocations as a means of offsetting recent population declines. (JOURNAL OF WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT 73(3):362–367; 2009) DOI: 10.2193/2007-207 KEY WORDS Florida Keys, genetic, marsh rabbit, mitochondrial DNA, population structure, Sylvilagus palustris hefneri. The Lower Keys marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris hefneri)is (Forys and Humphrey 1999b). -

Iguanas in Florida N Green and Spinytail Iguanas Are Native to Central and South America, but Are Commonly Found in the Exotic Pet Trade

Iguana fast facts n Iguanas are large lizards that can grow over 4 feet in length. Iguanas in Florida n Green and spinytail iguanas are native to Central and South America, but are commonly found in the exotic pet trade. n Iguanas bask in open areas and are often seen on sidewalks, docks, patios, decks, in trees or open mowed areas. n They can run or climb swiftly when frightened and dive into water or retreat into burrows or thick foliage. n Green iguanas can range from green to Black spinytail iguana, Adam G. Stern grayish black in color and have a row of spikes down the center of the head and back. n During the breeding season, adult male green iguanas can sometimes take on an orange hue. n Spinytail iguanas can range from gray to dark tan in color with black bands and have whorls of spiny scales on the tail. n Green iguanas are mainly herbivores and feed primarily on leaves, flowers and fruits of Mexican spinytail iguana, Kenneth L. Krysko various broad-leaved herbs, shrubs and trees, but will feed on other items opportunistically. If you have further questions or need more n Spinytail iguanas are omnivorous, eating help, call your regional Florida Fish and primarily vegetation, but have been Wildlife Conservation Commission office: documented eating small animals and eggs. Three members of the iguana family are now established in South Florida and occasionally observed in other parts of Florida: the green Main Headquarters iguana, the Mexican spinytail iguana, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission black spinytail iguana.