Iguana 11.3 B&W Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

Lord Howe Island, a Riddle of the Pacific, Part III

Lord Howe Island, A Riddle of the Pacific, Part III S. J. PARAMONOV1 IN THIS FINAL PART (for parts I and II see During two visits to the island, in 1954 and Pacif.Sci.12 (1) :82- 91, 14 (1 ): 75-85 ) the 1955, the author failed to find the insect. An author is dealing mainly with a review of the official enquiry was made recently to the Ad insects and with general conclusions. mini stration staff of the island, and the author received a letter from the Superintendent of INSECTA the Island, Mr. H. Ward, on Nov. 3, 1961, in which he states : "A number of the old inhabi Our knowledge of the insects of Lord Howe tants have been questioned and all have advised Island is only preliminary and incomplete. Some that it is at least 30 years and possibly 40 groups, for example butterflies and beetles, are years since this insect has .been seen on the more or less sufficiently studied, other groups Island. A member of the staff, aged 33 years, very poorly. has never seen or heard of the insect, nor has Descriptions of new endemic species and any pupil of the local School." records of the insects of the island are dis The only possibility is that the insect may persed in many articles, and a summary of our still exist in one of the biggest banyan trees knowledge in this regard is lacking. However, on the slope of Mr, Gower, on the lagoon side. a high endemism of the fauna is evident. Al The area is well isolated from the settlement though the degree of endemi sm is only at the where the rat concentration was probably the specific, or at most the generic level, the con greatest, and may have survived in crevices of nection with other faunas is very significant. -

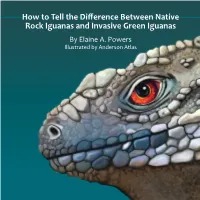

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum

Zootaxa 4138 (2): 381–391 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4138.2.10 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:683BD945-FE55-4616-B18A-33F05B2FDD30 Rediscovery of the 220-year-old holotype of the Banded Iguana, Brachylophus fasciatus (Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum IVAN INEICH1 & ROBERT N. FISHER2 1Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, UMR 7205 (CNRS, EPHE, MNHN, UPMC; ISyEB: Institut de Systéma- tique, Évolution et Biodiversité), CP 30 (Reptiles), 25 rue Cuvier, F-75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Diego Field Station, 4165 Spruance Road, Suite 200, San Diego, CA 92101-0812, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Paris Natural History Museum herpetological collection (MNHN-RA) has seven historical specimens of Brachylo- phus spp. collected late in the 18th and early in the 19th centuries. Brachylophus fasciatus was described in 1800 by Brongniart but its type was subsequently considered as lost and never present in MNHN-RA collections. We found that 220 year old holotype among existing collections, registered without any data, and we show that it was donated to MNHN- RA from Brongniart’s private collection after his death in 1847. It was registered in the catalogue of 1851 but without any data or reference to its type status. According to the coloration (uncommon midbody saddle-like dorsal banding pattern) and morphometric data given in its original description and in the subsequent examination of the type in 1802 by Daudin and in 1805 by Brongniart we found that lost holotype in the collections. -

ISG News 9(1).Indd

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 9 • Number 1 • Summer 2006 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and onservation Centers for Species Survival Formed j Cyclura spp. were awareness programs that help Cselected as a taxa of mutual concern under a new agreement between a select ensure the survival of wild group of American zoos and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The zoos - under iguanas and their habitats. the banner of Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2) - and USFWS have pledged to work cooperatively to advance conservation of the selected spe- cies by identifying specific research projects, actions, and opportunities that will significantly and clearly support conservation efforts. Cyclura are the only lizards selected under the joint program. The zoos participating in the program include the San Diego Wild Animal Park, Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, The Wilds, White Oak Conservation Center and the National Zoo’s Conservation and Research Center. USFWS participation will be coordinated by Bruce Weissgold in the Division of Management Authority (bruce_weissgold @fws.gov). IN THIS ISSUE News & Comments ............... 1 RCC Facility at Fort Worth j The Fort Worth Zoo recently opened their Animal Outreach and Conservation Center (ARCC) in an off-exhibit Iguanas in the News ............... 3 A area of the zoo. The $1 million facility actually consists of three separate units. Taxon Reports ...................... 7 The primary facility houses the zoo’s outreach collection, while a state-of-the-art B. vitiensis ...................... 7 reptile conservation greenhouse will highlight the zoo’s work with endangered C. pinguis ..................... 9 iguanas and chelonians. -

Sauromalus Hispidus

ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS Cerdá-Ardura & Langarica-Andonegui 2018 - Sauromalus hispidus in Rasa Island- p 17-28 ON THE PRESENCE OF THE SPINY CHUCKWALLA SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) IN RASA ISLAND, MEXICO PRESENCIA DEL CHACHORÓN ESPINOSO SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) EN LA ISLA DE RASA, MÉXICO Adrián Cerdá-Ardura1* and Esther Langarica-Andonegui2 1Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Uiversidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CDMX, México. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Abstract.— In 2006 and 2013 two different individuals of the Spiny Chuckwalla (Sauromalus hispidus) were found on the small, flat, volcanic and isolated Rasa Island, located in the Midriff Region of the Gulf of California, Mexico. This species had never been recorded from Rasa Island prior to 2006. A new field study in 2014 revealed the presence of a single female chuckwalla inhabiting the Tapete Verde Valley, in the south-central part of the island, occupying a territory no bigger than 10000 m2. A scat analysis shows that the only food consumed by the animal is the Alkali Weed (Cressa truxilliensis) that forms patches of carpets in its habitat. The individual is in precarious condition, as it seems to starve on a seasonal basis, especially during El Niño cycles; also, it is missing fingers and toes, which appear to be intentional markings by amputation. We conclude that the two individuals were introduced to the island intentionally by humans. Keywords.— Chuckwalla, Gulf of California, Rasa Island. Resumen.— En 2006 y 2013 se encontraron dos individuos diferentes del cachorón de roca o chuckwalla espinoso (Sauromalus hispidus) en la pequeña, plana, volcánica y aislada isla Rasa, localizada en la Región de las Grandes Islas, en el Golfo de California, México. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Boidae, Boinae): a Rare Snake from the Vale Do Ribeira, State of São Paulo, Brazil

SALAMANDRA 47(2) 112–115 20 May 2011 ISSNCorrespondence 0036–3375 Correspondence New record of Corallus cropanii (Boidae, Boinae): a rare snake from the Vale do Ribeira, State of São Paulo, Brazil Paulo R. Machado-Filho 1, Marcelo R. Duarte 1, Leandro F. do Carmo 2 & Francisco L. Franco 1 1) Laboratório de Herpetologia, Instituto Butantan, Av. Vital Brazil, 1500, São Paulo, SP, CEP: 05503-900, Brazil 2) Departamento de Agroindústria, Alimentos e Nutrição. Escola Superior de Agronomia “Luiz de Queiroz” – ESALQ/USP, Av. Pádua Dias, 11 C.P.: 9, Piracicaba, SP, CEP: 13418-900, Brazil Correspondig author: Francisco L. Franco, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 9 December 2010 The boid genusCorallus Daudin, 1803 is comprised of nine Until recently, only four specimens (including the above Neotropical species (Henderson et al. 2009): Corallus an mentioned holotype) of C. cropanii were deposited in her- nulatus (Cope, 1876), Corallus batesii (Gray, 1860), Co petological collections: three in the Coleção Herpetológica rallus blombergi (Rendahl & Vestergren, 1941), Coral “Alphonse Richard Hoge”, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, lus caninus (Linnaeus, 1758), Corallus cookii Gray, 1842, Corallus cropanii (Hoge, 1954), Corallus grenadensis (Bar- bour, 1914), Corallus hortulanus (Linnaeus, 1758), and Corallus ruschenbergerii (Cope, 1876). The most conspic- uous morphological attributes of representatives of these species are the laterally compressed body, robust head, slim neck, and the presence of deep pits in some of the la- bial scales (Henderson 1993a, 1997). Species of Corallus are distributed from northern Central American to south- ern Brazil, including Trinidad and Tobago and islands of the south Caribbean. Four species occur in Brazil: Corallus batesii, C. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica.