Sauromalus Hispidus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

The Natural World That I Seek out in the Desert Regions of Baja California

The natural world that I seek out in the desert regions of Baja California and southern California provides me with scientific adventure, excitement towards botany, respect for nature, and overall feelings of peace and purpose. Jon P. Rebman, Ph.D. has been the Mary and Dallas Clark Endowed Chair/Curator of Botany at the San Diego Natural History Museum (SDNHM) since 1996. He has a Ph.D. in Botany (plant taxonomy), M.S. in Biology (floristics) and B.S. in Biology. Dr. Rebman is a plant taxonomist and conducts extensive floristic research in Baja California and in San Diego and Imperial Counties. He has over 15 years of experience in the floristics of San Diego and Imperial Counties and 21 years experience studying the plants of the Baja California peninsula. He leads various field classes and botanical expeditions each year and is actively naming new plant species from our region. His primary research interests have centered on the systematics of the Cactus family in Baja California, especially the genera Cylindropuntia (chollas) and Opuntia (prickly-pears). However, Dr. Rebman also does a lot of general floristic research and he co- published the most recent edition of the Checklist of the Vascular Plants of San Diego County. He has over 22 years of field experience with surveying and documenting plants including rare and endangered species. As a field botanist, he is a very active collector of scientific specimens with his personal collections numbering over 22,500. Since 1996, he has been providing plant specimen identification/verification for various biological consulting companies on contracts dealing with plant inventory projects and environmental assessments throughout southern California. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Taxonomy and Distribution of Opuntia and Related Plants

Taxonomy and Distribution of Opuntia and Related Genera Raul Puente Desert Botanical Garden Donald Pinkava Arizona State University Subfamily Opuntioideae Ca. 350 spp. 13-18 genera Very wide distribution (Canada to Patagonia) Morphological consistency Glochids Bony arils Generic Boundaries Britton and Rose, 1919 Anderson, 2001 Hunt, 2006 -- Seven genera -- 15 genera --18 genera Austrocylindropuntia Austrocylindropuntia Grusonia Brasiliopuntia Brasiliopuntia Maihuenia Consolea Consolea Nopalea Cumulopuntia Cumulopuntia Opuntia Cylindropuntia Cylindropuntia Pereskiopsis Grusonia Grusonia Pterocactus Maihueniopsis Corynopuntia Tacinga Miqueliopuntia Micropuntia Opuntia Maihueniopsis Nopalea Miqueliopuntia Pereskiopsis Opuntia Pterocactus Nopalea Quiabentia Pereskiopsis Tacinga Pterocactus Tephrocactus Quiabentia Tunilla Tacinga Tephrocactus Tunilla Classification: Family: Cactaceae Subfamily: Maihuenioideae Pereskioideae Cactoideae Opuntioideae Wallace, 2002 Opuntia Griffith, P. 2002 Nopalea nrITS Consolea Tacinga Brasiliopuntia Tunilla Miqueliopuntia Cylindropuntia Grusonia Opuntioideae Grusonia pulchella Pereskiopsis Austrocylindropuntia Quiabentia 95 Cumulopuntia Tephrocactus Pterocactus Maihueniopsis Cactoideae Maihuenioideae Pereskia aculeata Pereskiodeae Pereskia grandiflora Talinum Portulacaceae Origin and Dispersal Andean Region (Wallace and Dickie, 2002) Cylindropuntia Cylindropuntia tesajo Cylindropuntia thurberi (Engelmann) F. M. Knuth Cylindropuntia cholla (Weber) F. M. Knuth Potential overlapping areas between the Opuntia -

A Test with Sympatric Lizard Species

Heredity (2016) 116, 92–98 & 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/16 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Does population size affect genetic diversity? A test with sympatric lizard species MTJ Hague1,2 and EJ Routman1 Genetic diversity is a fundamental requirement for evolution and adaptation. Nonetheless, the forces that maintain patterns of genetic variation in wild populations are not completely understood. Neutral theory posits that genetic diversity will increase with a larger effective population size and the decreasing effects of drift. However, the lack of compelling evidence for a relationship between genetic diversity and population size in comparative studies has generated some skepticism over the degree that neutral sequence evolution drives overall patterns of diversity. The goal of this study was to measure genetic diversity among sympatric populations of related lizard species that differ in population size and other ecological factors. By sampling related species from a single geographic location, we aimed to reduce nuisance variance in genetic diversity owing to species differences, for example, in mutation rates or historical biogeography. We compared populations of zebra-tailed lizards and western banded geckos, which are abundant and short-lived, to chuckwallas and desert iguanas, which are less common and long-lived. We assessed population genetic diversity at three protein-coding loci for each species. Our results were consistent with the predictions of neutral theory, as the abundant species almost always had higher levels of haplotype diversity than the less common species. Higher population genetic diversity in the abundant species is likely due to a combination of demographic factors, including larger local population sizes (and presumably effective population sizes), faster generation times and high rates of gene flow with other populations. -

Sex-Specific Behavioral Strategies for Thermoregulation in the Comon Chuckwalla (Sauromalus Ater) ______

SEX-SPECIFIC BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES FOR THERMOREGULATION IN THE COMON CHUCKWALLA (SAUROMALUS ATER) ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology ____________________________________ By Emily Rose Sanchez Thesis Committee Approval: Christopher R. Tracy, Department of Biological Science, Chair Sean E. Walker, Department of Biological Science Paul Stapp, Department of Biological Science Spring, 2018 ABSTRACT Intraspecific variability of behavioral thermoregulation in lizards due to habitat, temperature availability, and seasonality is well documented, but variability due to sex is not. Sex-specific thermoregulatory behaviors are important to understand because they can affect relative fitness in ways that result in different responses to environmental changes. The common chuckwalla (Sauromalus ater) is a great model for investigating sex differences in thermoregulation because males behave differently from females while they actively defend distinct territories while females may not. I recorded body temperatures of wild adult chuckwallas continuously from May to July 2016, as well as operative environmental temperatures in crevices and aboveground sites used by chuckwallas for basking. I compared the effect of sex on indices of thermoregulatory accuracy and effectiveness, aboveground activity, and the time chuckwallas selected body temperatures relative -

Geographical Structure and Cryptic Lineages Within Common Green

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 50–62 ORIGINAL Geographical structure and cryptic ARTICLE lineages within common green iguanas, Iguana iguana Catherine L. Stephen1*, Vı´ctor H. Reynoso2, William S. Collett1, Carlos R. Hasbun3 and Jesse W. Breinholt4 1Department of Biology, Utah Valley ABSTRACT University, Orem, UT, USA, 2Coleccio´n Aim Our aim was to investigate genetic structure in Neotropical populations Nacional de Anfibios y Reptiles, of common green iguanas (Iguana iguana) and to compare that structure with Departamento de Zoologı´a, Universidad Nacional Auto´noma de Me´xico, Mexico, DF, past geological events and present barriers. Additionally, we compared levels of Me´xico, 3Fundacio´n Zoolo´gica de El Salvador, divergence between lineages within Iguana with those within closely related San Salvador, El Salvador, 4Department of genera in the subfamily Iguaninae. Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Location Neotropics. UT, USA Methods DNA sequence data were collected at four loci for up to 81 individ- uals from 35 localities in 21 countries. The four loci, one mitochondrial (ND4) and three nuclear (PAC, NT3, c-mos), were chosen for their differences in coa- lescent and mutation rates. Each locus was analysed separately to generate gene trees, and in combination in a species-level analysis. Results The pairwise divergence between Iguana delicatissima and I. iguana was much greater than that between sister species of Conolophus and Cyclura and non-sister species of Sauromalus, at both mitochondrial (mean 10.5% vs. 1.5–4%, respectively) and nuclear loci (mean 1% vs. 0–0.18%, respectively). Furthermore, divergences within I. iguana were equal to or greater than those for interspecific comparisons within the outgroup genera. -

Tail Bifurcation Recorded in Sauromalus Ater

Herpetology Notes, volume 10: 363-364 (2017) (published online on 03 July 2017) Tail bifurcation recorded in Sauromalus ater Daniel Koleska¹,*, Veronika Svobodová¹, Tomáš Husák¹, Martin Kulma¹ and Daniel Jablonski² Sauromalus ater Duméril, 1856 is a desert member and Walker, 2013), Tropiduridae (Passos et al., 2014; of the family Iguanidae distributed in the Sonoran Martins et al., 2013). Supernumerary tails are considered and Mojave deserts in southwestern United States and to be a result of a previous injury rather than congenital northwestern Mexico, where it inhabits rocky flats and malformation (Lynn, 1950). Although e.g., Bateman and hillsides. It reaches a total length of approximately 50 Fleming (2009) mention that caudal autotomy appears cm, while the tail may reach half of this length. Herein, we report a case of tail bifurcation in an imported individual of S. ater held in captivity in Zoopark Zájezd, Zájezd, Czech Republic, recorded in this species for the first time. On 24 October 2015 staff of Zoopark Zájezd received a shipment of two imported individuals of S. ater. One of the individuals (an adult female) had a bifurcated tail (Fig. 1A). According to the importer, the individual was already caught with this anomaly. The bifurcation was located 89 mm posterior to the cloaca. The supernumerary tails were of different length (Fig. 1B). The longer tail measured 18 mm while the shorter tail was 7 mm long. Snout-to-vent length (SVL) of the individual was 123 mm, vent-to-tail length (VTL) was 107 mm. Although the individual was in poor nutritional condition, it had no other visible malformations or injuries. -

Iguanas and Other Lizards

ANIMALS OF THE WORLD Iguanas and Other Lizards Why do iguanas sunbathe? Why does an iguana stick out its tongue? Which lizard is often mistaken for a snake? Read Iguanas and Other Lizards to find out! What did you learn? QUESTIONS 1. A lizard is a ... 4. The only lizard to have its own national a. Reptile park is the ... b. Mammal a. Komodo dragon c. Bird b. Blue iguana d. Fish c. Helmeted lizard d. Chameleon 2. The only lizard to live in the sea is the ... 5. What type of lizard is this? a. Gila monster b. Blue iguana c. Cape dwarf gecko d. Galapagos marine iguana 3. The smallest type of iguana is the ... a. Green iguana 6. What type of lizard is this? b. Chuckwalla c. Anole d. Desert iguana TRUE OR FALSE? _____ 1. An iguana has a three- _____ 4. Lizards head-bob as a method of chambered heart. communication. _____ 2. A green iguana can grow up to _____ 5. The largest living lizard is the 5 feet long. Komodo dragon. _____ 3. Lizards are warm-blooded. _____ 6. The green iguana is often mistaken for a snake. © World Book, Inc. All rights reserved. ANSWERS 1. a. Reptile. According to section “What Is a 4. a. Komodo dragon. According to section Lizard?” on page 6, we know that “A lizard is “Which Lizard Has Its Own National Park?” a reptile.” So, the correct answer is A. on page 38, we know that “The Komodo dragon has its own national park.” So, the 2. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disturbance, Restoration, and Soil Carbon Dynamics in Desert and Tropical Ecosystems a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disturbance, Restoration, and Soil Carbon Dynamics in Desert and Tropical Ecosystems A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Biology by Amanda Cantu Swanson September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Edith B. Allen, Chairperson Dr. G. Darrel Jenerette Dr. James O. Sickman Copyright by Amanda Cantu Swanson 2017 The Dissertation of Amanda Cantu Swanson is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my principal advisor, Dr. Edith B. Allen, for seeing my potential when I was a student volunteer and for encouraging me to be a restoration and plant ecologist. She has been a wonderful mentor, resource, and colleague, and her guidance has enabled me to succeed in graduate school. Working in her lab has been an invaluable experience that will serve me throughout my career. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Michael F. Allen, who informally co-advised me during my Ph.D. He has also been an incredible teacher and supporter, whose wisdom and creativity have further inspired me to ask novel scientific questions and pursue a career in research. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members Dr. G. Darrel Jenerette and Dr. James Sickman for their unwavering support and guidance. Several other faculty and collaborators have generously given their time, resources, and support to help me with my dissertation: Dr. Emma Aronson, Dr. Cameron Barrows, Jon Botthoff, Dr. Diego Dierick, Dr. Mark De Guzman, Mark Fisher, Dr. Rebecca Hernandez, Dr. Liyin Liang, Dr. Allen Muth, Dr. -

0616 Sauromalus Varius.Pdf

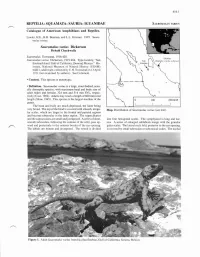

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: IGUANIDAE r'- Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Lawler, H.E., K.R. Beaman, and L.L. Grismer. 1995. Sauro- malus varius. Sauromalus varius Dickerson Piebald Chuckwalla Sauromalus Townsend, 1916:428. Sauromalus varius Dickerson, 1919:464. qpe-locality, "San Esteban Island, Gulf of California, [Sonora] Mexico." Ho- lotype, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 64441, adult male, collected by C.H. Townsend on 13 April 191 1 (not examined by authors). See Comment. Content. This species is monotypic. Definition. Sauromalus varius is a large. stout-bodied, sexu- ally dimorphic species, with maximum head and body size of adult males and females 324 mm and 314 mm SVL, respec- tively (Case, 1982). Adults may reach a length of 600 mm total length (Shaw, 1945). This species is the largest member of the genus. The head and body are much depressed, the latter being very broad. The top of the head is covered with smooth, irregu- - Map. Distribution of Sauromalus varius (see text). lar scales, which are larger in the frontal and parietal regions and become tubercular in the latter region. The superciliaries and the supraoculars are small and juxtaposed. Aseries of short, ~ntofour hexagonal scales. The symphyseal is long and nar- smooth suboculars, following the contour of the orbit, pass up- row. A series of enlarged sublabials merge with the granular ward and posteriorly to the anterior border of the ear opening. gular scales. The lateral neck fold, posterior to the ear opening, The labials are minute and juxtaposed. The rostra1 is divided 1s covered by small tubercular or subconical scales. -

Common Chuckwalla (Sauromalus Ater): Behavior

NATURAL HISTORY NOTE Common Chuckwalla ( Sauromalus ater ): Behavior Howard O. Clark, Jr. H. T. Harvey & Associates, Fresno, California, USA. [email protected] The Common Chuckwalla ( Sauromalus ater ) is a large, diurnal, heliothermic, iguanid lizard occurring in the desert regions of southeastern California, western Arizona, and in portions of Nevada, Utah, and Mexico (Johnson, 1965; Werman, 1982). The species is re- stricted to rocky areas and volcanic outcrops within its range (Smith, 1946; Nagy, 1973). Chuckwallas escape from predators in a unique manner. Their habitat consists of numerous cracks and crevices that they use as refuge. Smith (1946) not- ed that chuckwallas he observed were very wary and slipped easily into concealment while he was several Figure 1. Common Chuckwalla ( Sauromalus ater ) near rock bolders. hundred feet away. Likewise, Johnson (1965) reported Photo by K.W. Hughes, near Ridgecrest, CA. that chuckwallas moved without hesitation headfirst into these cracks when approached. When found in There were other crevices nearby, but apparently this rock crevices, the lizards swell their bodies by inflat - particular crevice had an important characteristic When found in ing their lungs which wedges them tightly between the that I was unable to determine. Perhaps because the rock crevices, rock surfaces, making removal practically impossible. chuckwalla appeared to be an immature, it may not Here I describe the behavior of a chuckwalla using have learned avoidance behavior by using several the lizards swell a rock crevice as a retreat. On 17 June 2006 I was cracks as refuge, especially after a particular crack their bodies by hiking along a trail on an unnamed hill near Ridgecrest, exposed it as vulnerable to potential harm.