Cfreptiles & Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

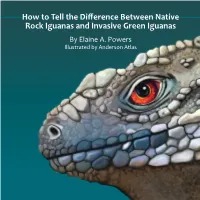

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Iguana Iguana

Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil To cite this version: Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil. Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2015, 10 (6), 10.1371/journal.pone.0127575. hal-01901355 HAL Id: hal-01901355 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01901355 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic Evidence of Hybridization between the Endangered Native Species Iguana delicatissima and the Invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

ISG News 9(1).Indd

Iguana Specialist Group Newsletter Volume 9 • Number 1 • Summer 2006 The Iguana Specialist Group News & Comments prioritizes and facilitates conservation, science, and onservation Centers for Species Survival Formed j Cyclura spp. were awareness programs that help Cselected as a taxa of mutual concern under a new agreement between a select ensure the survival of wild group of American zoos and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The zoos - under iguanas and their habitats. the banner of Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2) - and USFWS have pledged to work cooperatively to advance conservation of the selected spe- cies by identifying specific research projects, actions, and opportunities that will significantly and clearly support conservation efforts. Cyclura are the only lizards selected under the joint program. The zoos participating in the program include the San Diego Wild Animal Park, Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, The Wilds, White Oak Conservation Center and the National Zoo’s Conservation and Research Center. USFWS participation will be coordinated by Bruce Weissgold in the Division of Management Authority (bruce_weissgold @fws.gov). IN THIS ISSUE News & Comments ............... 1 RCC Facility at Fort Worth j The Fort Worth Zoo recently opened their Animal Outreach and Conservation Center (ARCC) in an off-exhibit Iguanas in the News ............... 3 A area of the zoo. The $1 million facility actually consists of three separate units. Taxon Reports ...................... 7 The primary facility houses the zoo’s outreach collection, while a state-of-the-art B. vitiensis ...................... 7 reptile conservation greenhouse will highlight the zoo’s work with endangered C. pinguis ..................... 9 iguanas and chelonians. -

Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes Auropunctatus) in North America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2018 Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America Are R. Berentsen USDA National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] William C. Pitt Smithsonian Institute Robert T. Sugihara USDA/APHIS/WS/National Wildlife Research Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Berentsen, Are R.; Pitt, William C.; and Sugihara, Robert T., "Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2034. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2034 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Government Publication Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services Ecology of the Small 12 Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America Are R. Berentsen, William C. Pitt, and Robert T. Sugihara CONTENTS General Ecology and Distribution......................................................................... -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Roatán Spiny-Tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura Oedirhina) Conservation Action Plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A

Roatán spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura oedirhina) Conservation action plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A. Pasachnik, Ashley B.C. Goode and Tandora D. Grant INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,400 government and NGO members and almost 15,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by around 950 staff in more than 50 countries and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org IUCN Species Programme The IUCN Species Programme supports the activities of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and individual Specialist Groups, as well as implementing global species conservation initiatives. It is an integral part of the IUCN Secretariat and is managed from IUCN’s international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. The Species Programme includes a number of technical units covering Wildlife Trade, the Red List, Freshwater Biodiversity Assessments (all located in Cambridge, UK), and the Global Biodiversity Assessment Initiative (located in Washington DC, USA). IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of more than 9,000 experts. -

Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER

Volume 27 (April 2017), 201–216 Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER Published by the British Predation of Jamaican rock iguana Cyclura( collei) nests Herpetological Society by the invasive small Asian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) and the conservation value of predator control Rick van Veen & Byron S. Wilson Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, Mona 7, Kingston, Jamaica The introduced small Asian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) has been widely implicated in extirpations and extinctions of island taxa. Recent studies and anecdotal observations suggest that the nests of terrestrial island species are particularly vulnerable to mongoose predation, yet quantitative data have remained scarce, even for species long assumed to be at risk from the mongoose. We monitored nests of the Critically Endangered Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei) to determine nest fate, and augmented these observations with motion-activated camera trap images to document the predatory behaviour of the mongoose. Our data provide direct, quantitative evidence of high nest predation pressure attributable to the mongoose, and together with reported high rates of predation on hatchling and juvenile iguanas (also by the mongoose), support the original conclusion that the mongoose was responsible for the apparent lack of recruitment and the aging structure of the small population that was ‘re-discovered’ in 1990. Encouragingly however, our data also demonstrate a significant reduction in nest predation pressure within an experimental mongoose-removal area. Thus, our results indicate that otherwise catastrophic levels of nest loss (at or near 100%) can be ameliorated or even eliminated by removal trapping of the mongoose. We suggest that such targeted control efforts could also prove useful in safeguarding other threatened insular species with reproductive strategies that are notably vulnerable to mongoose predation (e.g., the incubation of eggs on or underground). -

Iguanas in Florida N Green and Spinytail Iguanas Are Native to Central and South America, but Are Commonly Found in the Exotic Pet Trade

Iguana fast facts n Iguanas are large lizards that can grow over 4 feet in length. Iguanas in Florida n Green and spinytail iguanas are native to Central and South America, but are commonly found in the exotic pet trade. n Iguanas bask in open areas and are often seen on sidewalks, docks, patios, decks, in trees or open mowed areas. n They can run or climb swiftly when frightened and dive into water or retreat into burrows or thick foliage. n Green iguanas can range from green to Black spinytail iguana, Adam G. Stern grayish black in color and have a row of spikes down the center of the head and back. n During the breeding season, adult male green iguanas can sometimes take on an orange hue. n Spinytail iguanas can range from gray to dark tan in color with black bands and have whorls of spiny scales on the tail. n Green iguanas are mainly herbivores and feed primarily on leaves, flowers and fruits of Mexican spinytail iguana, Kenneth L. Krysko various broad-leaved herbs, shrubs and trees, but will feed on other items opportunistically. If you have further questions or need more n Spinytail iguanas are omnivorous, eating help, call your regional Florida Fish and primarily vegetation, but have been Wildlife Conservation Commission office: documented eating small animals and eggs. Three members of the iguana family are now established in South Florida and occasionally observed in other parts of Florida: the green Main Headquarters iguana, the Mexican spinytail iguana, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission black spinytail iguana.