Section 4. Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Quill Villa Roma

Seni r BuzzSUMMER 2019 The Official Publication of the TWU Local 100 Retirees Association • 195 Montague 3rd Floor • Brooklyn NY 11201 NOSTALGIC PHOTOS from back in the day Page 3 Retirees Remember September Outing to the Great VILLA MIKE ROMA QUILL Planned- Page 18 Fondly Pages 4-5 www.twulocal100.org/retirees-association Director’s Letter by Mike Tutrone, Director, TWU Local 100 Retirees Association I am happy to announce that at our last executive board meeting a couple of changes were introduced and passed in our quest to improve the lot of TWU Retiree Association members. Change number one was that Effective June 1, 2019, all the benefits in our Hospital Stay Program will be doubled, the weekly hospital income will rise from $150.00 to $300.00 per week, and all other benefits will rise accordingly. Change number two is that the Retiree Association will now cover the cost of your Defensive Driving course, see the listing of classes here at the Union Hall. For those of you who are unable to take advantage of the classes at the union hall, merely send us a copy of the course completion certificate and a copy of your payment receipt and we will reimburse you. This benefit is capped at $25.00 per member, spouse is included if you have a family membership. Mike Quill Film Prescriptions Thanks to all, who have contributed to the By now everyone should have received their new MIKE QUILL documentary film that Is prescription cards from CVS Caremark, if you have being produced and directed by not received them call the MTA BSC at 646-376-0123 Macdara Vallely (See the page and request a new card. -

MTA New York City Subway� S N

WESTCHESTER THE BRONX R 2 k I a V r Wakefield t E PELHAM R Wakefield Wakefield–241 St m D Woodlawn Norwood–205 St Pelham Bay Park A BAY Van Cortlandt Pk–242A St 241 St Subway 2 L E Subway 4 PARK Subway D 2 Subway 6 Subway 19 A EASTCHESTER V B 5 NYC Transit Bus R P O NYC Transit Bus Y O NYC Transit Bus Nereid Av CIT NYC Transit Bus NYC Transit Bus A T Eastchester Bx41OP Webster Av/White Plains Rd R D fi - T Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av (238 St) 3 S CO W Bx10 Riverdale 23 Dyre Av Bx5 Bruckner Blvd/Story Av W Bx9 Broadway/West Farms Sq A A Y Bx34 Bainbridge Av 2•5 Bee-Line N W 254 ST Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av Bx12 Pelham Pkwy/Bay Plaza S Riverdale 5 H 40 Westchester County Med Ctr I Bee-Line Bx28 E Gun Hill Rd Woodlawn 233 St Bx12 Orchard Beach N Bee-Line G T 1 Yonkers/Hastings • Baychester 41 WestchesterV County Med Ctr 4 Yonkers Bx30 Boston Rd/E Gun Hill Rd 2 5 A Bx14 Country Club–Parkchester O N Av W 1C Westchester Cty Comm Coll 42 New Rochelle 20 White Plains Bx34 Bainbridge Av 225 ST CO-OP O Bx29 Bay Plaza–City Island B 5 T L R V 1T Tarrytown M 225 St 222 ST CITY A 21 White Plains Metro-North D 1 O h B t Queens Surface L S r • 1W White Plains A 2 5 D H o C R N QBx1 Co-op City–Flushing O 2 Yonkers 9 - O ORCHARD L 4 N o d N r U O t I BEACH T 219 St A Van Cortlandt Park e BAYCHESTER 3 White Plains Bee-Line MTA New York City Subway S n M A 242 St 2•5 O THE VAN Woodlawn V 45 Eastchester B V u Y A 1•9 CORTLANDT 4 Y P Marble Hill–225 St I A E N PARK K K Gun Hill Rd W W o RIVERDALE D Gun Hill Rd R V W P SO Williams U K E D BRONX A K B Subway 19 A R -

New York City Department of Transportation

NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Passenger Transport Division Battery Maritime Bldg, Third Floor New York, NY 10004 (212) 487-8300 Web Site: http://www.ci.nyc.ny.us/html/dot/home.html State Legislative Districts: Senate: 7, 9 - 23, 25 - 34 Assembly: 16, 17, 20 - 58, 62 - 83 The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) sponsors seven private transit operators within New York City including: Command Bus, Green Bus Lines, Jamaica Buses, Queens Surface, Triboro Coach, Liberty Lines Express, and New York Bus Tours. NYCDOT also contracts with Atlantic Express to provide two express routes for commuters from the South Shore of Staten Island. The NYCDOT bus system is comprised of 1,300 buses, the 9th largest fleet and the largest privately operated fleet in the nation and more than 1/4 the size of the MTA NYC Transit bus fleet. that involved three companies: Queens Surface, Five of seven original operators provide local and Jamaica Buses and Triboro Coach. The first strike express service, while two provide exclusively express lasted only two days, February 28 and 29. However, service. Together, there are 35 express and 47 local the second strike was more prolonged, lasting five and routes. Liberty Lines and New York Bus Tours provide a half weeks, from June 29 to August 6. Each day of express services from the Bronx to Manhattan. Green the strike led to the loss of approximately 193,000 Bus Lines, Jamaica Buses, Queens Surface and Triboro riders. In the aftermath of the strike there was a Coach provide local service in Queens and express residual impact period before ridership returned to service from Queens to Manhattan. -

How Can We Maximize Private Sector Participation in Transportation?—Part Ii

HOW CAN WE MAXIMIZE PRIVATE SECTOR PARTICIPATION IN TRANSPORTATION?—PART II HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENERGY POLICY, NATURAL RESOURCES AND REGULATORY AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 30, 2004 Serial No. 108–277 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 98–605 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:01 Mar 10, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\98605.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM TOM DAVIS, Virginia, Chairman DAN BURTON, Indiana HENRY A. WAXMAN, California CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut TOM LANTOS, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida MAJOR R. OWENS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DOUG OSE, California DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio RON LEWIS, Kentucky DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri ADAM H. PUTNAM, Florida DIANE E. WATSON, California EDWARD L. SCHROCK, Virginia STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland NATHAN DEAL, Georgia LINDA T. -

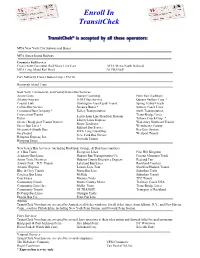

List of Transitchek Operators

Enroll In TransitChek MTA New York City Subway and Buses MTA Staten Island Railway Commuter Rail Services Connecticut Commuter Rail/Shore Line East MTA Metro-North Railroad MTA Long Island Rail Road NJ TRANSIT Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corp. (PATH) Roosevelt Island Tram New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania Bus Services Arrow Lines Harran Coachway Peter Pan Trailways Atlantic Express HART Bus Service Queens Surface Corp. * Coastal Link Huntington Area Rapid Transit Spring Valley Coach Collins Bus Service Jamaica Buses * Sunrise Coach Lines Command Bus Company * Kelley Transportation Swift Transportation Connecticut Transit Leprechaun Line/Hendrick Hudson Trans-Bridge Lines Datco Triboro Coach Corp. * Liberty Lines Express Greater Bridgeport Transit District Martz Trailways Waterbury Northeast Transit Green Bus Lines * Westchester County— Milford Bus Service Greenwich Shuttle Bus MTA Long Island Bus Bee-Line System Greyhound New York Bus Service Westport Transit Hampton Express, Inc. Norwalk Transit Hampton Jitney New Jersey Bus Services (including Rockland, Orange, & Dutchess counties) A-1 Bus Tours Evergreen Lines Pine Hill-Kingston Academy Bus Lines Hudson Bus Transportation Co. Pocono Mountain Trails Anton Travel Services Hudson County Executive Express Red and Tan Asbury Park—N.Y. Transit Lakeland Bus Lines Rockland Coaches Atlantic Express Leisure Line Tour Shortline/Hudson Transit Blue & Grey Transit Martz Bus Line Suburban Trails Carefree Bus Lines McRide Suburban Transit Coachways Monsey Trails TPC Transit Community Coach Morris County Metro Trailway Coach USA Community Lines Inc. Muller Tours Trans-Bridge Lines Community Transit NJ TRANSIT Transport of Rockland DeCamp Bus Lines Olympia Trails Drogin Bus Co. Peter Pan Line Amtrak TransitChek Vouchers are accepted by Amtrak at all ticket windows, for all ticket types, from Albany, N.Y., and New Haven, Conn., south to Philadelphia, including New York Penn Station, and Newark Penn Station. -

Green Bus Lines

Analysis of Routes and Ridership of a Franchise Bus Service: Green Bus Lines for New York City Department of Transportation Claire E. McKnight Jose Holguin-Veras Herb Levinson Robert E. Paaswell University Transportation Research Center Region II at City College of New York October 2000 Revised December 2000 Acknowledgments This project could not have been done without the help of a great many people. First of all were the people at New York City Department of Transportation, particularly LuAnn Dunbar, Richard Cohen, and Bill Hough. At Green Bus, we want to thank Doris Drantch, Dave Popiel, Larry Hughes, and Felice Farber. Martin Krieger, Senior Director of Operations Planning, was very generous in sharing with us the ridership numbers for NYCT Queens bus routes. Thurston Clark, Queens Surface, provided information on the electronic fareboxes. Additionally the research team at the University Transportation Research Center consisted of the four authors plus the following associates and students: Andrew Sakawizc Angel Medina Camille Kamga Ellen Thorson Sunanda Patharanage Chang Guan 1: Introduction Ridership on buses throughout New York City has been increasing in the last several years due to the combination of the economic boom and the use of Metrocard which allows passengers to make free transfers between subways and buses. The response to the free transfer was perhaps greater in Queens, where many neighborhoods were far from subways and previously using a bus to access the subway required paying two fares. This “two fare zone,” among other characteristics of Queens, led to the prevalence of the dollar vans, which diverted a significant share of the bus passengers. -

Nikki Haley Resigns As UN Amb; Israel Loses Staunch Advocate for Truth

The Jewish Voice: More Jewish News than the NYT, NY Post & the WSJ Combined October 12, 2018 | 3 Cheshvan 5779 Vol. 15, Iss. 41 www.TJVNews.com $1 Nikki Haley Resigns as UN Amb; Israel Loses Staunch Advocate for Truth In a shocking revelation on Tuesday, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley announced her resignation from her post at the world agency, and thusly, has fueled speculation concerning her future career endeavors. «It has been an honor of a lifetime,» Haley said, addressing both President Trump and journalists in the Oval Office. Photo Credit: UNinfo.com By: Fern Sidman of resignation on Wednesday, Oct. 3. will help reduce violence and hopefully me. She’s done an incredible job. She’s the United Nations. I mean, votes that Haley is not leaving her position at the bring peace to that troubled country. a fantastic person,” Trump said. “She’s we would normally get ‘No’ votes, we’re n a shocking revelation on Tues- UN until the end of the year. We stood up for our ally Israel and done a fantastic job, and we’ve done a getting very strong votes now. So, I just day, U.S. ambassador to the United “As a strong supporter of term lim- began to roll back the UN’s relentless fantastic job together. We’ve solved a lot want to thank Nikki.” Nations, Nikki Haley announced its, I have long believed that rotation bias against her. We reformed UN op- of problems, and we’re in the process of “We will miss you,” Trump said to her resignation from her post at in offic benefits the public,” Haley’s erations and saved over $1.3 billion. -

Transit Program Funding\Chapter2

2001 Annual Report on Public Transportation Assistance Programs in New York State April, 2002 Passenger Transportation Division New York State Department of Transportation Albany, New York 12232-0414 This report was developed, in part, by utilizing Federal Transit Administration Technical Study Grants TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I INTRODUCTION I-1 II TRANSIT FINANCE AND CAPITAL ASSISTANCE II-1 Statewide Mass Transportation Operating Assistance Program II-1 Background II-1 General Fund II-1 Mass Transportation Operating Assistance Fund II-1 Dedicated Mass Transportation Trust Fund II-4 Locally Generated Subsidies II-4 Payments to Transit Systems II-5 FFY 2001 Federal Transit Allocations and Apportionments II-8 Urbanized Area Formula Program II-8 Non-Urbanized and Elderly and Persons with Disabilities Program II-10 Fixed Guideway Modernization II-10 New Start Funding II-11 Discretionary Bus II-11 Jobs Access and Reverse Commute II-11 Over-the-Road Bus Accessibility Program II-12 FFY 2002 Transportation Appropriations Act Related Provisions II-12 2001 Capital Annual Report II-14 State Capital Assistance Programs for Non-MTA Transit Systems II-14 State Omnibus and Transit Purpose Program II-14 State Transit Dedicated Funds (SDF) II-14 Flexible Transfers to Transit II-15 Obligations and Expenditures II-15 Non-MTA Capital Program Area Emphasis II-15 Bus Replacement II-16 Bus Maintenance and Storage Facilities II-16 Intermodal Transportation Facilities II-17 Other Continuing Transit Capital Needs II-17 III STATUS AND PERFORMANCE OF MAJOR TRANSIT -

A Directory of Regularly Scheduled, Fixed Route, Local Public

A DIRECTORY OF REGULARLY SCHEDULED, FIXED ROUTE, LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION SERVICE IN URBANIZED AREAS OVER 50,000 POPULATION AUGUST 1981 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Urban Mass Transportation Administration Office of Planning, Management and Demonstrations Washington, D.C. 20590 . FOR RELEASE MONDAY UMTA Technical Notice 2-81 August 10, 1981 The U. S. DeDartment of Transportation's Urban Mass Transportation Administration released today an updated directory of 686 local fixed route transit operations in 279 urbanized areas (UZAs) of over 50,000 population. As shown in the summaries on page 19, the vehicle requirements for weekday schedules in these UZAs are 3,566 commuter rail cars, 7,450 rapid transit cars, 551 light rail cars, 42,925 motor coaches, 503 trolley coaches and 28 cable cars. These figures are peak requirements, not fleet size. For purposes of this compilation, a transit operation is a fixed route, regularly scheduled service, available to the general public, offering rides wholly within, or commuter rides from outside a particular UZA. Maps showing UZA borders appear in U.S. Census Bureau publication PC (1)-A, by states. UZA listings are in the order of population rank. To find a particular UZA, refer to page 1, where UZAs are listed alphabetically, or to page 21, where they are listed by states. Users of this directory desiring to identify systems of a certain size, or operating different modes, will find useful information in column 5. This directory replaces Technical Notice 2-80 dated August 1, 1 980. Another listing in this series is TN 1-81 dated March 9, 1981, reporting services available in communities of less than 50 ,000 population. -

Travel Survey Manual Appendices

Travel Survey Manual Appendices Travel Model Improvement Program Travel Survey Manual - A~~endices June 1996 Prepared by Cambridge Systematic, Inc. Prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Transit Administration Federal Highway Administration Office of the Secretary U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Appendix A The Costs of Travel Surveys The Costs of Travel Surveys Travel surveyors are almost always constrained by limited available resources. More often than not, the survey design and sampling tasks are bounded by funding limits, so the survey team needs to be able to esti- mate the cost of various types of surveys early in their effort. Estimating Costs Based on Previous Survey Efforts The most common source of rough cost estimates is the reported costs of previous efforts. The costs of travel survey efforts are often reported in technical papers and reports. In addition, rules-of-thumb about survey costs are commonly cited. For instance, many surveyors use a figure of $100 per completed survey for telephone-mail-telephone household travel surveys. Unfortunately, there are several problems with relying on past survey experience in estimating costs: ● The analyses rarely account for inflation; ● The analyses do not account for deteriorating cooperation rates over time; ● The analyses do not account for geographic differences; ● It is often difficult to determine which survey cost elements are included in the past cost estimates; and ● It is highly unlikely that the past efforts will include the same survey design=le-ments and sampling considerations as the survey team’s pro- posed effort. To analyze the cost of a past survey effort, the survey team needs to account for inflation. -

Northeast Queens BUS STUDY

Northeast Queens BUS STUDY METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY SEPTEMBER 2015 , , Metropolitan Transportation Authority CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 65 SUMMARY OF CHANGES 1. INTRODUCTION 3 SHORT‐TERM RECOMMENDATIONS Methodology Service Change Characteristics of Northeast Queens Schedule Changes LONG‐TERM RECOMMENDATIONS 2. BUS SERVICE AND SCHEDULE 9 Service Changes Current Service Downtown Flushing Bus Terminal Service Coverage 2010 Service Changes 7. NEXT STEPS 72 Other Recent & Upcoming Service Changes Schedule Changes APPENDICES __ Appendix A ‐ Public Input Questions and Answers 3. BUS RIDERSHIP 23 Appendix B – Route Profiles 3‐Year Ridership Trend Appendix C – Additional Data 1‐Year Ridership Trend Senior/Student Ridership Bus Stop Usage Origins and Destinations Transfers Classifying Northeast Queens Bus Transfers 4. QUALITY OF SERVICE 42 PERFORMANCE Wait Assessment On‐Time Performance Running Time Road Reliability Bus Speeds Vision Zero COMFORT+ENVIRONMENT Passenger Environment Loading Guidelines Schedule Guidelines Bus Stop Furniture CUSTOMER COMMUNICATION 5. PUBLIC INPUT 55 Service Issues Schedules Issues Amenities and Facilities Issues Other Issues I , Metropolitan Transportation Authority LIST OF TABLES Table 37 – Passenger Environment Survey – Local & Table 1 – Travel Time to Work on Public Limited Transportation in NE Queens Table 38 – Passenger Environment Survey ‐ Express Table 2 – Bus Service Guidelines Table 39 – Current Loading Levels Compared to Table 3 – Bus Service Frequency Changes Loading Guidelines -

Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation Subsector

September 2008 sUbsector Profile Employment in New York City’s Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation Subsector About this Profile n Urban transit is almost entirely pub- This is one of four profiles1 developed by the lic sector with virtually no role for the pri- New York City Labor Market Information vate in the United States, with exception of Service (NYCLMIS) about the transportation paratransit (special van and bus services for sector’s top employment subsectors. The people with disabilities, the elderly and the others are about air transportation, truck infirm), which is often contracted out. transportation, and support activities for n Ground passenger transportation is transportation. dominated by the private sector: charter This profile is intended to help workforce buses, private shuttle services, school buses, development account executives with and privately owned taxis and limousines. business development and job placement, career advisors with job counseling, and Because the subsector is organized into education and training professionals with two distinct sets of industry groups, there their activities in the transit and ground are three kinds of information in this profile. passenger transportation subsector. Job- Information about: seekers can also use this information to 1) The public sector industry group within help with career decision-making. Icons the subsector — Urban Transit (4851); appear throughout this profile to mark find- 2) The private sector industry groups in ings and recommendations of special inter- the subsector — Ground Passenger Trans- est to these respective audiences. See page portation (4852-4859); and 2 for a guide on How to Use this Profile, 3) The whole subsector, both public and and an accompanying key to the icons.