A Baseline Study of Alpine Snowbed and Rill Communities on Mount Washington, Nh Author(S): Robert S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dicranum Scoparium Broom Fork-Moss Key 129, 135, 139

Dicranales Dicranum scoparium Broom Fork-moss Key 129, 135, 139 5 mm 5 mm 1 cm Identification A medium- to large-sized plant (up to 10 cm), growing in yellow-green to dark green cushions or large patches. The leaves are 4–7.5 mm long, narrowly spearhead-shaped and taper to a long fine tip composed largely of the strong nerve. They are often somewhat curved, but can also be straight and are hardly altered when dry. The leaf margins are usually strongly toothed near the tip. The back of the nerve has raised lines of cells which are just visible with a hand lens. These are also toothed, making the tip of the leaf appear toothed all round. D. scoparium occasionally produces deciduous shoots with smaller leaves at the tip of the stems. The curved, cylindrical capsule is common in the north and west of Britain, and is borne on a long seta that is yellow above and reddish below. Similar species D. scoparium is quite variable and confusion is most likely with D. majus (p. 379) and D. fuscescens (p. 382). D. majus is a larger plant with longer, regular, strongly curved leaves showing little variation; if in doubt, your plant is almost certainly D. scoparium. D. fuscescens is similar in size to D. scoparium, but has a finer leaf tip with smaller teeth on the margins and lacks raised lines of cells on the back of the leaves. The leaves in D. fuscescens are crisped when dry, and in this state mixed stands of D. scoparium and D. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

The Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Biochemical Compounds of Dicranum Scoparium and Porella Platyphylla

Aydın S. 2020. Anatolian Bryol……………………………………………………………..……………19 Anatolian Bryology http://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/anatolianbryology Anadolu Briyoloji Dergisi Research Article DOI: 10.26672/anatolianbryology.701466 e-ISSN:2458-8474 Online The free radical scavenging activities of biochemical compounds of Dicranum scoparium and Porella platyphylla Sevinç AYDIN1* 1Çemişgezek Vocational School, Munzur University, Tunceli, TURKEY Received: 10.03.2020 Revised: 28.03.2020 Accepted: 17.04.2020 Abstract The bryophytes studies carried out in our country are mainly for bryofloristic purposes and the studies on biochemical contents are very limited. Dicranum scoparium and Porella platyphylla taxa of bryophytes were used in the present study carried out to determine the free radical scavenging activities, fatty acid, and vitamin contents. In this study, it was aimed to underline the importance of bryophytes for scientific literature and to provide a basis for further studies on this subject. The data obtained in this study indicate that the DPPH radical scavenging effect of D. scoparium taxon is significantly higher than that of P. platyphylla taxon. It is known that there is a strong relationship between the phenolic compound content of methanol extracts of the plants and the DPPH radical scavenging efficiency. When the fatty acid contents were examined, it was observed that levels of all unsaturated fatty acids were higher in the P. platyphylla taxon than the D. scoparium taxon, except for α-Linolenic acid. When the vitamin contents of species were compared, it was determined that D-3, α -tocopherol, stigmasterol, betasterol amount was higher in Dicranum taxon. Keywords: DPPH, Fatty Acid, Vitamin, Dicranaceae, Porellaceae Dicranum scoparium ve Porella platyphylla taxonlarının biyokimyasal bileşiklerinin serbest radikal temizleme faaliyetleri Öz Ülkemizde briyofitler ile ilgili olan çalışmalar genellikle briyofloristik amaçlı olup serbest radikal temizleme aktiviteleri ve yağ asidi içerikleri gibi diğer amaçlı çalışmalar yok denecek kadar azdır. -

Clonal Structure in the Moss, Climacium Americanum Brid

Heredity 64 (1990) 233—238 The Genetical Society of Great Britain Received 25August1989 Clonal structure in the moss, Climacium americanum Brid. Thomas R. Meagher* and * Departmentof Biological Sciences, Rutgers University, P.O. Box 1059, Jonathan Shawt Piscataway, NJ 08855-1059. 1 Department of Biology, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY 14850. The present study focussed on the moss species, Climacium americanum Brid., which typically grows in the form of mats or clumps of compactly spaced gametophores. In order to determine the clonal structure of these clumps, the distribution of genetic variation was analysed by an electrophoretic survey. Ten individual gametophores from each of ten clumps were sampled in two locations in the Piedmont of North Carolina. These samples were assayed for allelic variation at six electrophoretically distinguishable loci. For each clump, an explicit probability of a monomorphic versus a polymorphic sample was estimated based on allele frequencies in our overall sample. Although allelic variation was detected within clumps at both localities, our statistical results showed that the level of polymorphism within clumps was less than would be expected if genetic variation were distributed at random within the overall population. INTRODUCTION approximately 50 per cent of moss species that are hermaphroditic, self-fertilization of bisexual Ithas been recognized that in many taxa asexual gametophytes results in completely homozygous propagation as the predominant means of repro- sporophytes. Dispersal of such genetically -

Apn80: Northern Spruce

ACID PEATLAND SYSTEM APn80 Northern Floristic Region Northern Spruce Bog Black spruce–dominated peatlands on deep peat. Canopy is often sparse, with stunted trees. Understory is dominated by ericaceous shrubs and fine- leaved graminoids on high Sphagnum hummocks. Vegetation Structure & Composition Description is based on summary of vascular plant data from 84 plots (relevés) and bryophyte data from 17 plots. l Moss layer consists of a carpet of Sphag- num with moderately high hummocks, usually surrounding tree bases, and weakly developed hollows. S. magellanicum dominates hum- mocks, with S. angustifolium present in hollows. High hummocks of S. fuscum may be present, although they are less frequent than in open bogs and poor fens. Pleurozium schre- beri is often very abundant and forms large mats covering drier mounds in shaded sites. Dicranum species are commonly interspersed within the Pleurozium mats. l Forb cover is minimal, and may include three-leaved false Solomon’s seal (Smilacina trifolia) and round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia). l Graminoid cover is 5-25%. Fine-leaved graminoids are most important and include three-fruited bog sedge (Carex trisperma) and tussock cottongrass (Eriophorum vagi- natum). l Low-shrub layer is prominent and dominated by ericaceous shrubs, particularly Lab- rador tea (Ledum groenlandicum), which often has >25% cover. Other ericads include bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia), small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos), and leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata). Understory trees are limited to scattered black spruce. l Canopy is dominated by black spruce. Trees are usually stunted (<30ft [10m] tall) with 25-75% cover . Some sites have scattered tamaracks in addition to black spruce. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with Emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium QI-YING, CAI1, 2, BI-CAI, GUAN2, GANG, GE2, YAN-MING, FANG 1 1 College of Biology and the Environment, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China. 2 College of Life Science, Nanchang University, 330031 Nanchang, China. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We present molecular phylogenetic investigation of Thuidiaceae, especially on Thudium and Pelekium. Three chloroplast sequences (trnL-F, rps4, and atpB-rbcL) and one nuclear sequence (ITS) were analyzed. Data partitions were analyzed separately and in combination by employing MP (maximum parsimony) and Bayesian methods. The influence of data conflict in combined analyses was further explored by two methods: the incongruence length difference (ILD) test and the partition addition bootstrap alteration approach (PABA). Based on the results, ITS 1& 2 had crucial effect in phylogenetic reconstruction in this study, and more chloroplast sequences should be combinated into the analyses since their stability for reconstructing within genus of pleurocarpous mosses. We supported that Helodiaceae including Actinothuidium, Bryochenea, and Helodium still attributed to Thuidiaceae, and the monophyletic Thuidiaceae s. lat. should also include several genera (or species) from Leskeaceae such as Haplocladium and Leskea. In the Thuidiaceae, Thuidium and Pelekium were resolved as two monophyletic groups separately. The results from molecular phylogeny were supported by the crucial morphological characters in Thuidiaceae s. lat., Thuidium and Pelekium. Key words: Thuidiaceae, Thuidium, Pelekium, molecular phylogeny, cpDNA, ITS, PABA approach Introduction Pleurocarpous mosses consist of around 5000 species that are defined by the presence of lateral perichaetia along the gametophyte stems. Monophyletic pleurocarpous mosses were resolved as three orders: Ptychomniales, Hypnales, and Hookeriales (Shaw et al. -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

Pre-European Colonization 1771 1809 1819 1826 1840 July 23, 1851

MOVED BY MOUNTAINS In this woodblock by In the first big wave of trail building, The Abenaki Presence Endures Marshall Field, Ethan Hiker-Built Trails Deepen Pride of Place Allen Crawford is depicted hotel owners financed the construction carrying a bear, one of the of bridle paths to fill hotel beds and cater For millennia, Abenaki people traveled on foot and by canoe many legends that gave the By the late 19th century, trails throughout the region for hunting, trading, diplomacy and White Mountains an allure to a growing leisure class infatuated by were being built by walkers for that attracted luminaries, “the sublime” in paintings and writings. war. The main routes followed river corridors, as shown such as Daniel Webster, walkers in the most spectacular in this 1958 map by historian and archaeologist Chester Henry David Thoreau and This inset is from a larger 1859 map and Nathaniel Hawthorne. settings. Hiking clubs developed Price. By the late 1700s, colonialism, disease, warfare and drawing by Franklin Leavitt. distinct identities, local loyalties European settlement had decimated native communities. GLADYS BROOKS MEMORIAL LIBRARY, MOUNT WASHINGTON OBSERVATORY and enduring legacies. Their main foot trails were taken over and later supplanted by stagecoach roads, railroads and eventually state highways. DARTMOUTH DIGITAL LIBRARY COLLECTIONS “As I was standing on an Grand Hotels Build Trails for Profit old log chopping, with my WONALANCET OUT DOOR CLUB Native footpaths axe raised, the log broke, The actual experience of riding horseback on a For example, the Wonalancet Out Door Club developed its identity were often faint and I came down with bridle path was quite a bit rougher than suggested around its trademark blue sign posts, its land conservation advocacy to modern eyes by this 1868 painting by Winslow Homer. -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

University of Cape Town

The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University of Cape Town Addendum (1) Soon after submitting this thesis a more recent comprehensive classification by Crandall-Stotler et al. (2009)1 was published. This recent publication does not undermine the information presented in this thesis. The purpose of including the comprehensive classification of Crandall-Stotler and Stotler (2000) was specifically to introduce some of the issues regarding the troublesome classification of this group of plants. Crandall-Stotler and Stotler (2000), Grolle and Long (2000) for Europe and Macaronesia and Schuster (2002) for Austral Hepaticae represent three previously widely used yet differing opinions regarding Lophoziaceae classification. They thus reflect a useful account of some of the motivation for initiating this project in the first place. (2) Concurrently or soon after chapter 2 was published by de Roo et al. (2007)2 more recent relevant papers were published. These include Heinrichs et al. (2007) already referred to in chapter 4, and notably Vilnet et al. (2008)3 examining the phylogeny and systematics of the genus Lophozia s. str. The plethora of new information regarding taxa included in this thesis is encouraging and with each new publication we gain insight and a clearer understanding these fascinating little plants. University of Cape Town 1 Crandall-Stotler, B., Stotler, R.E., Long, D.G. 2009. Phylogeny and classification of the Marchantiophyta. -

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY and POPULATION STRUCTURE of GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS of NATURAL HISTORY and CONSERVATION EFFORTS a Thesis B

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2017 Department of Biology ! THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY December 2017 APPROVED BY: Matt C. Estep Chairperson, Thesis Committee Zack E. Murrell Member, Thesis Committee Ray Williams Member, Thesis Committee Zack E Murrell Chairperson, Department of Biology Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies ! Copyright by Nikolai M. Hay 2017 All Rights Reserved ! Abstract THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS Nikolai M. Hay B.S., Appalachian State University M.S., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Matt C. Estep Geum radiatum is a federally endangered high-elevation rock outcrop endemic herb that is widely recognized as a hexaploid and a relic species. Little is currently known about G. radiatum genetic diversity, population interactions, or the effect of augmentations. This study sampled every known population of G. radiatum and used microsatellite markers to observe the alleles present at 8 loci. F-statistics, STRUCTURE, GENODIVE, and the R package polysat were used to measure diversity and genetic structure. The analysis demonstrates that there is interconnectedness and structure of populations and was able to locate augmented and punitive hybrids individuals within an augmented population. Geum radiautm has diversity among and between populations and suggests current gene flow in the northern populations. -

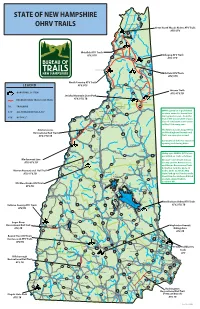

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide.