Who Is Really Protecting Barbie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mattel V Walking Mountain Productions.Malted Barbie

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT MATTEL INC., a Delaware Corporation, No. 01-56695 Plaintiff-Appellant, C.D. Cal. No. v. CV-99-08543- RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, a California Business Entity; TOM N.D. Cal. No. FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a CV-01-0091 Walking Mountain Productions, Misc. WHA Defendants-Appellees. MATTEL INC., a Delaware No. 01-57193 Corporation, Plaintiff-Appellee, C.D. Cal. No. CV-99-08543- v. RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, N.D. Cal. No. a California Business Entity; TOM CV-01-0091 FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a Misc. WHA Walking Mountain Productions, Defendants-Appellants. OPINION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Ronald S.W. Lew, District Judge, Presiding and United States District Court for the Northern District of California William H. Alsup, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 6, 2003—Pasadena, California 18165 18166 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS Filed December 29, 2003 Before: Harry Pregerson and Sidney R. Thomas, Circuit Judges, and Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior District Judge.* Opinion by Judge Pregerson *The Honorable Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior Judge, United States Dis- trict Court for the District of Columbia, sitting by designation. 18170 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS COUNSEL Adrian M. Pruetz (argued), Michael T. Zeller, Edith Ramirez and Enoch Liang, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart Oliver & Hedges, LLP, Los Angeles, California, for the plaintiff-appellant- cross-appellee. Annette L. Hurst (argued), Douglas A. Winthrop and Simon J. Frankel, Howard, Rice, Nemerovski, Canady, Falk & Rab- kin, APC, San Francisco, California, and Peter J. -

An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer

Cybaris® Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Schreyer, Amanda (2015) "An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests," Cybaris®: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Schreyer: An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balanci Published by Mitchell Hamline Open Access, 2015 1 Cybaris®, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2015], Art. 3 AN OVERVIEW OF LEGAL PROTECTION FOR FICTIONAL CHARACTERS: BALANCING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE INTERESTS † AMANDA SCHREYER I. Fictional Characters and the Law .............................................. 52! II. Legal Basis for Protecting Characters ...................................... 53! III. Copyright Protection of Characters ........................................ 57! A. Literary Characters Versus Visual Characters ............... 60! B. Component Parts of Characters Can Be Separately Copyrightable ................................................................ -

Beebe - Trademark Law: an Open-Source Casebook

Beebe - Trademark Law: An Open-Source Casebook III. Defenses to Trademark Infringement and Related Limitations on Trademark Rights ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 A. Descriptive Fair Use ............................................................................................................... 3 1. Descriptive Fair Use and Consumer Confusion ................................................ 3 KP Permanent Make-Up, Inc. v. Lasting Impression I, Inc. .................... 4 2. The Three-Step Test for Descriptive Fair Use ................................................ 10 Dessert Beauty, Inc. v. Fox ................................................................................. 10 Sorensen v. WD-40 Company ........................................................................... 21 3. Further Examples of Descriptive Fair Use Analyses .................................... 27 International Stamp Art v. U.S. Postal Service ......................................... 27 Bell v. Harley Davidson Motor Co. .................................................................. 29 Fortune Dynamic, Inc. v. Victoria’s Secret.................................................. 30 B. Nominative Fair Use ........................................................................................................... 32 1. The Three-Step Test for Nominative Fair Use ................................................ 32 Toyota Motor Sales, -

Interns Volunteer at TMC Health Fair

Vol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014 Page 4 Cleveland University quick quiz Wanna win big? inVol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014touch It’s fun and easy to play. And you really A newsletter for the students, faculty & staff of Cleveland University-Kansas City don’t need a big brain to win. Just do a little research, either on the Interns volunteer at TMC health fair leveland Chiropractic College Linda Gerdes, community outreach Internet or otherwise, Pe ter Conce again answered the call manager, worked with Moore and Dr. to serve others as a large contingent Debra Robertson-Moore to prepare for and you’ll be well of Clevelanders participated in the 4th the health fair. Although the commit- on your way! Annual Touchdown Family Fest, July 19 ment of time and energy were substan- at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. tial, the results were worth the effort. Sponsored by Truman Medical Center “There is a lot of time and work in- To enter the “Quick Quiz” (TMC), the day-long event offered free, volved in organizing such a large event,” basic health care services to those in need, Gerdes said. “But when you see all the trivia contest, submit your That’s so totally random. including dental and vision screenings for people you are helping, it makes all the answer either via email to children and adults, as well as adult phys- hard work worth it, and hopefully teaches [email protected] A little more than nine years ago, we launched the first in a series of “totally random” trivia questions icals and youth sports physicals. -

Confusion Isn't Everything William Mcgeveran University of Minnesota Law School

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 89 | Issue 1 Article 6 11-2013 Confusion Isn't Everything William McGeveran University of Minnesota Law School Mark P. McKenna University of Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation 89 Notre Dame L. Rev. 253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\89-1\NDL106.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-NOV-13 9:31 CONFUSION ISN’T EVERYTHING† William McGeveran* and Mark P. McKenna** The typical shorthand justification for trademark rights centers on avoiding consumer con- fusion. But in truth, this encapsulation mistakes a method for a purpose: confusion merely serves as an indicator of the underlying problems that trademark law seeks to prevent. Other areas of law accept confusion or mistake of all kinds, intervening only when those errors lead to more serious harms. Likewise, every theory of trademark rights considers confusion troubling solely because it threatens more fundamental values such as fair competition or informative com- munication. In other words, when it comes to the deep purposes of trademark law, confusion isn’t everything. Yet trademark law’s structure now encourages courts to act otherwise, as if confusion itself were the ultimate evil with which trademark law is concerned and as if its optimal level were zero. -

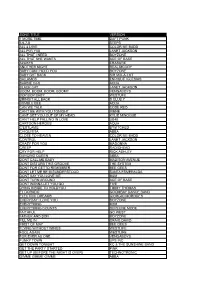

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Mattel, Inc. V. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 36 Number 3 Symposium: ICANN Governance Article 7 3-1-2003 Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons Tamar Buchakjian Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tamar Buchakjian, Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons, 36 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 1321 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol36/iss3/7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MA TTEL, INC. V. MCA RECORDS, INC.: LET'S PARTY IN BARBIE'S WORLD-EXPANDING THE FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT TO MUSICAL PARODY OF CULTURAL ICONS I. INTRODUCTION On July 24, 2002, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc. -a case that may have a substantial impact on reaching a balance between the interests of trademark owners of cultural icons and the First Amendment rights of musical parodists of those cultural icons. By ruling in favor of the defendants, the Ninth Circuit held that the use of the "Barbie" trademark in a musical parody (1) was not an infringement of the toy manufacturer's trademark associated with the Barbie doll because the song was not likely to confuse the consumer as to its source or sponsorship, and (2) was not actionable under the Federal Trademark 2 Dilution Act (FTDA) as diluting the Barbie trademark3 because the song fell within the noncommercial use exception. -

1 I'm a BARBIE GIRL By: Jim Astrachan

attorneys at law . a professional corporation I'M A BARBIE GIRL By: Jim Astrachan __________________________________ Judge Alex Kozinski's Mattel v. Universal Music International opinion ribs Mattel's attempt to prevent parodic use of its Barbie trademark holding, "If this were a sci-fi melodrama, it might be called Speech-zilla meets Trademark Kong." This case is a well reasoned opinion in which Judge Kozinski analyses a trademark owner's right to prevent use of its mark in an infringing manner and a third person's right to use the mark to lampoon the product associated with the mark. A trademark is a word, phrase or symbol used to identify a manufacturer or sponsor of goods or a provider of service. Barbie is a registered mark used by Mattel to designate a doll that it manufactures and to identify Mattel as the source of the product. If any other doll manufacturer was to apply the Barbie mark to its doll product it is not hard to imagine that an appreciable number of consumers would believe Mattel was the source. The principal purpose of trademark rights is to avoid this sort of confusion in the marketplace. When another's trademark is used in a way that is likely to cause confusion, 99001.003/51027 1 infringement results. Once infringement is shown irreparable harm is presumed and injunctive relief is appropriate. But as Judge Kozinski points out, trademarks are used for more than product identification purposes. Some become part of our vocabulary and run the risk of becoming generic. He asks, "How else do you say something's the 'Rolls Royce' of its class?" We add trademarks to our vocabulary and we often use those marks to sound contemporary. -

Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: the Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2017 Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law Jane C. Ginsburg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Jane C. Ginsburg, Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law, JOURNAL OF THE COPYRIGHT SOCIETY OF THE USA, VOL. 65, P. 245, 2018; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 14-567 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2072 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [forthcoming, Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA] Intellectual Property as Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law Jane C. Ginsburg* Abstract Some years ago, caselaw on trademark parodies and similar unauthorized “speech” uses of trademarks could have led one to conclude that the law had no sense of humor. Over time, however, courts in the US and elsewhere began to leaven likelihood of confusion analyses with healthy skepticism regarding consumers’ alleged inability to perceive a joke. These decisions did not always expressly cite the copyright fair use defense, but the considerations underlying the copyright doctrine seemed to inform trademark analysis as well. -

Annals of the University of Craiova, Series

Annals of the University of Craiova ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII DIN CRAIOVA ANNALES DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE CRAIOVA ANNALS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CRAIOVA SERIES: PHILOLOGY -ENGLISH- * YEAR XVIII, NO. 1-2, 2017 1 Annals of the University of Craiova ANNALS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CRAIOVA 13, Al. I. Cuza ROMANIA We make exchanges with similar institutions in Romania and abroad ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII DIN CRAIOVA Str. Al. I. Cuza, nr. 13 ROMÂNIA Efectuăm schimburi cu instituţii similare din ţară şi din străinătate ANNALES DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE CRAIOVA 13, Rue Al. I. Cuza ROUMANIE On fait des échanges des publications avec les institutions similaires du pays et de l’étranger EDITORS General editor: Aloisia Sorop, University of Craiova, Romania Assistant editor: Ana-Maria Trantescu, University of Craiova, Romania Editorial secretary: Diana Otat, University of Craiova, Romania Reviewers: Professor Sylvie Crinquand, University of Bourgogne, Dijon, France Associate Professor Patrick Murphy, Nord University, Norway Professor Mariana Neagu, “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Romania Associate Professor Rick St. Peter, Northwestern State University, USA Associate Professor Melanie Shoffner, James Madison University, USA Dieter Wessels, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany Associate Professor Anne-Lise Wie, Nord University, Norway The authors are fully responsible for the originality of their papers and for the accuracy of their notes. 2 Issue coordinators: Associate Professor Florentina Anghel, PhD Associate Professor Madalina Cerban, PhD Senior Lecturer Claudia Pisoschi, PhD Senior Lecturer Mihai Cosoveanu, PhD CONTENTS FLORENTINA ANGHEL Past and Present in T.S.Eliot’s Avant-Garde Poetry ………………… 7 ARDA ARIKAN Characters as Animals in Dreiser’s Sister Carrie ....................... 16 SORIN CAZACU Culture Clash in Toni Morrison's Tar Baby ............................. -

Organizations in Greater Seattle

Seatt'p Public Library UTERATUWE FEB 1 55 1978 Special New Year Edition Section A & Tm^MS(DIEHFlf, A Welcome Visitor to Greater Seattle Jewish Homes for SI Years Volume LI No. 15 Seattle, Washington September 3, 1975 yv -n> urn nr po (vwm rr£j>o mi inn D n KmucDi Page 2A The Jewish Transcript September 3,1975 Around the town . SAMUEL COHEN, Mercer Island realtor, boasts he's one of the original readers of the Transcript since its founding back in 1924, and follows it closely for news of the community . SAMUEL AND ALTHEA STROUM received a warm letter of appreciation from UW Pres. John R Hogness and Dean George M. Beckmann of the College of Arts and Sciences for their fund grant which made possible the upcoming Samuel and Althea Stroum Visiting Lec tureship in Jewish Studies there, starting in the fall. Pres. Hogness stressed the program will provide "a happy blend of scholarly and artistic achievement." MRS ESTHER SOLOMON of Capetown, South Africa, was a recent visitor in Seattle where for the first time, she met members of her family, including her cousins, Mrs. Frank Jones, Mrs. Ceorge Mosler and David Clazer and their families. During her stay, she was entertained and toured the Greater Seattle area . Seattle Sephardic Youth Federation, those between the ages of 18 and 25, visited Israel last month on a three-week tour, and included members Shelly Adatto, Terry and Tommy Damm, Stanley and Jean Ann Lorber and Sherry Rind, the latter former REUNITED AT LAST-former Prisoners of Zion Lassal Kaminsky and Lev Yagman (with dark glasses), office manager for The Jewish Transcript, who returns to both sentenced to five years hard labour in the second Leningrad trial of 1971 arrived in Israel, where they UW this month to continue her studies for her Master's and had a tearful reunion with their wives and children who had been allowed to immigrate earlier. -

A Parody of a Distinction: the Ninth Circuit's Conflicted Differentiation Between Parody and Satire, 20 Santa Clara High Tech

Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Volume 20 | Issue 3 Article 5 January 2004 A Parody of a Distinction: The inN th Circuit's Conflicted Differentiation between Parody and Satire Christopher J. Brown Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Christopher J. Brown, A Parody of a Distinction: The Ninth Circuit's Conflicted Differentiation between Parody and Satire, 20 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 721 (2003). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol20/iss3/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT A PARODY OF A DISTINCTION: THE NINTH CIRCUIT'S CONFLICTED DIFFERENTIATION BETWEEN PARODY AND SATIRE ChristopherJ. Brown f "Thou shalt not say that to rob the public is to steal."' I. INTRODUCTION In Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc. (Mattel),2 the Ninth Circuit recently held that a song based on the Barbie doll was a parody and therefore qualified for a fair use defense against a claim of trademark infringement.3 A few years ago, however, this same circuit in Dr. Seuss Enterprises,L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc. (Seuss)4 held that a book using the writing style of Dr. Seuss, as well as a character fashioned after the Cat in The Cat in the Hat, was a satire and therefore did not qualify for a fair use defense against claims of trademark and copyright infringement.