1 I'm a BARBIE GIRL By: Jim Astrachan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mattel V Walking Mountain Productions.Malted Barbie

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT MATTEL INC., a Delaware Corporation, No. 01-56695 Plaintiff-Appellant, C.D. Cal. No. v. CV-99-08543- RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, a California Business Entity; TOM N.D. Cal. No. FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a CV-01-0091 Walking Mountain Productions, Misc. WHA Defendants-Appellees. MATTEL INC., a Delaware No. 01-57193 Corporation, Plaintiff-Appellee, C.D. Cal. No. CV-99-08543- v. RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, N.D. Cal. No. a California Business Entity; TOM CV-01-0091 FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a Misc. WHA Walking Mountain Productions, Defendants-Appellants. OPINION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Ronald S.W. Lew, District Judge, Presiding and United States District Court for the Northern District of California William H. Alsup, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 6, 2003—Pasadena, California 18165 18166 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS Filed December 29, 2003 Before: Harry Pregerson and Sidney R. Thomas, Circuit Judges, and Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior District Judge.* Opinion by Judge Pregerson *The Honorable Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior Judge, United States Dis- trict Court for the District of Columbia, sitting by designation. 18170 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS COUNSEL Adrian M. Pruetz (argued), Michael T. Zeller, Edith Ramirez and Enoch Liang, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart Oliver & Hedges, LLP, Los Angeles, California, for the plaintiff-appellant- cross-appellee. Annette L. Hurst (argued), Douglas A. Winthrop and Simon J. Frankel, Howard, Rice, Nemerovski, Canady, Falk & Rab- kin, APC, San Francisco, California, and Peter J. -

Who Is Really Protecting Barbie

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 7-1-2008 Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attemps to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark Liz Somerstein Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Liz Somerstein, Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attemps to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark, 39 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 559 (2008) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol39/iss3/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attempts to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark Liz Somerstein* INTRODUCTION .............................................. 559 I. LEGAL REALISM: AN OVERVIEW ....................... 562 II. MATTEL'S AMERICAN BATTLE: MATTEL, INC. V. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS ................... 563 A. The Walking Mountain case: Background ........ 565 B. The Walking Mountain Court's Analysis ......... 567 i. Purpose and character of use ................ 568 ii. Nature of the copyrighted work .............. 570 iii. Amount and substantiality of the portion u sed ......................................... 570 iv. Effect upon the potential market ............ 571 III. AT LOOK AT WALKING MOUNTAIN UNDER THE LEGAL REALIST LENS ....................................... -

An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer

Cybaris® Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Schreyer, Amanda (2015) "An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests," Cybaris®: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Schreyer: An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balanci Published by Mitchell Hamline Open Access, 2015 1 Cybaris®, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2015], Art. 3 AN OVERVIEW OF LEGAL PROTECTION FOR FICTIONAL CHARACTERS: BALANCING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE INTERESTS † AMANDA SCHREYER I. Fictional Characters and the Law .............................................. 52! II. Legal Basis for Protecting Characters ...................................... 53! III. Copyright Protection of Characters ........................................ 57! A. Literary Characters Versus Visual Characters ............... 60! B. Component Parts of Characters Can Be Separately Copyrightable ................................................................ -

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Mourns Passing of Judge Pamela Ann Rymer

N E W S R E L E A S E September 22, 2011 Contact: David Madden (415) 355-8800 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Mourns Passing of Judge Pamela Ann Rymer SAN FRANCISCO – The Hon. Pamela Ann Rymer, a distinguished judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, died Wednesday, September 21, 2011, after a long illness. She was 69. Judge Rymer was diagnosed with cancer in 2009 and had been in failing health in recent months. She passed with friends at her bedside. “Judge Rymer maintained her calendar throughout her illness,” observed Ninth Circuit Chief Judge Alex Kozinski. “Her passion for the law and dedication to the work of the court was inspiring. She will be sorely missed by all of her colleagues.” Judge Rymer served on the federal bench at both the appellate and trial levels for more than 28 years. Nominated by President Reagan, she was appointed a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California on February 24, 1983. She was elevated to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals by President George H.W. Bush, receiving her commission on May 22, 1989. During her 22 years on the appellate court, Judge Rymer sat on more than 800 merits panels and authored 335 panel opinions. She last heard oral arguments in July and her most recent opinion was filed in August. Her productivity was remarkable and every case received her full attention, colleagues said. "Each case was intrinsically important to her. Finding the right answer for the parties and doing the law correctly were foremost in her mind in every matter. -

Sanai V. Kozinski

Case 3:19-cv-08162 Document 1 Filed 12/16/19 Page 1 of 53 1 Cyrus M. Sanai, SB#150387 SANAIS 2 433 North Camden Drive Suite 600 3 Beverly Hills, California, 90210 Telephone: (310) 717-9840 4 [email protected] 5 Pro Se 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 9 10 CYRUS SANAI, an individual, ) Case No.: ) 11 Plaintiff, ) vs. ) COMPLAINT FOR: 12 ) ALEX KOZINSKI, in his personal ) 13 capacity; CATHY CATTERSON, in her ) (1) INJUNCTIVE RELIEF FOR personal capacity; THE JUDICIAL ) VIOLATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL 14 COUNCIL OF THE NINTH CIRCUIT, ) RIGHTS ; an administrative agency of the United ) (2) MANDAMUS; 15 States; MOLLY DWYER, in her ) (3) DECLARATORY JUDGMENT; official capacity; SIDNEY THOMAS, ) (4) ABUSE OF PROCESS (FEDERAL 16 in his official and personal capacities; ) LAW); PROCTOR HUG JR., in his personal ) (5) MALICIOUS PROSECUTION 17 capacity; M. MARGARET ) (FEDERAL LAW); MCKEOWN, in her personal capacity; ) (6) WRONGFUL USE OF 18 RONALD M. GOULD, in his personal ) ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDINGS capacity; JOHNNIE B. RAWLINSON, ) (CALIFORNIA LAW); in her personal capacity; AUDREY B. ) (7) BIVENS CLAIM FOR DAMAGES 19 COLLINS, in her personal capacity; ) (8) RELIEF UNDER CALIFORNIA IRMA E. GONZALEZ, in her personal ) PUBLIC RECORDS ACT; 20 capacity; ROGER L. HUNT, in his ) (9) INJUNCTIVE RELIEF TO personal capacity; TERRY J. HATTER ) REMEDY FUTURE VIOLATION OF 21 JR., in his personal capacity; ROBERT ) CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS. H. WHALEY, in his personal capacity; ) 22 THE JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF ) CALIFORNIA, an administrative ) 23 agency of the State of California; and ) JURY DEMAND DOES 1-10, individuals and entities ) 24 whose identities and capacities are ) unknown; ) 25 ) Defendants. -

Interns Volunteer at TMC Health Fair

Vol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014 Page 4 Cleveland University quick quiz Wanna win big? inVol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014touch It’s fun and easy to play. And you really A newsletter for the students, faculty & staff of Cleveland University-Kansas City don’t need a big brain to win. Just do a little research, either on the Interns volunteer at TMC health fair leveland Chiropractic College Linda Gerdes, community outreach Internet or otherwise, Pe ter Conce again answered the call manager, worked with Moore and Dr. to serve others as a large contingent Debra Robertson-Moore to prepare for and you’ll be well of Clevelanders participated in the 4th the health fair. Although the commit- on your way! Annual Touchdown Family Fest, July 19 ment of time and energy were substan- at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. tial, the results were worth the effort. Sponsored by Truman Medical Center “There is a lot of time and work in- To enter the “Quick Quiz” (TMC), the day-long event offered free, volved in organizing such a large event,” basic health care services to those in need, Gerdes said. “But when you see all the trivia contest, submit your That’s so totally random. including dental and vision screenings for people you are helping, it makes all the answer either via email to children and adults, as well as adult phys- hard work worth it, and hopefully teaches [email protected] A little more than nine years ago, we launched the first in a series of “totally random” trivia questions icals and youth sports physicals. -

2006 Annual Report

NINTH CIRCUIT United States Courts 2006 Annual Report 2006 Annual Report Cover.indd 3 08/20/2007 8:55:02 AM Above: Text mural of Article III of the United States Constitution located at the Wayne Lyman Morse Courthouse in Eugene, Oregon. Cover Image: San Francisco courtroom mosaic depicting Justice with Science, Literature and the Arts The Offi ce of the Circuit Executive would like to acknowledge the following for their contributions to the 2006 Annual Report: Chief Judge Mary M. Schroeder Clerk of Court Cathy Catterson Chief Pretrial Services Offi cer George Walker Bankruptcy Appellate Panel Clerk Harold Marenus 2006 Annual Report Cover.indd 4 08/20/2007 8:55:04 AM Table of Contents Ninth Circuit Overview 2 Judicial Council Mission Statement 3 Foreword by Chief Judge Mary M. Schroeder 5 Ninth Circuit Overview 6 Judicial Council and Administration 8 Organization of Judicial Council Committees Judicial Transitions 10 New Judges 13 New Senior Judges 14 In Memoriam Ninth Circuit Highlights 16 Judicial Council Committees 19 2006 Ninth Circuit Judicial Conference 21 Conference Award Presentations 23 Devitt Award Presentation 25 Documentary Film Inspires Law Day Program 26 Ideas Set Forth for Managing Immigration Caseload 28 2006 National Gang Symposium Space and Facilities 30 Eugene Courthouse Dedicated 30 Space and Security Committee 33 Courthouses in Design Phase The Work of the Courts 36 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals 39 District Courts 43 Bankruptcy Courts 45 Bankruptcy Appellate Panel 47 Magistrate Judge Matters 49 Federal Public Defenders 51 Probation Offi ces 53 Pretrial Services Offi ces 55 District by District Caseloads (All statistics provided by the Administrative Offi ce of the United States Courts) 2006 Annual Report Final.indd Sec1:1 08/20/2007 8:49:04 AM The Judicial Council of the Ninth Circuit Annual Report 2006 Seated, from left: Chief District Judge Donald W. -

C:\Users\Johne\Downloads\ALA Court Memorial Program.Wpd

OPENING OF COURT UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS Cathy A. Catterson FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT Circuit and Court of Appeals Executive Special Court Session in Memory of PRESIDING and OPENING REMARKS The Honorable Sidney R. Thomas Chief Judge THE HONORABLE United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ARTHUR L. ALARCÓN REMARKS The Honorable Dorothy W. Nelson Senior Circuit Judge United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit The Honorable Deanell R. Tacha Dean, Pepperdine University School of Law Chief Judge Emeritus, United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (Retired) Richard G. Hirsch, Esq. Partner, Nasatir, Hirsch, Podberesky & Khero Thursday, June 4, 2015, 4:00 P.M. The Honorable Mary E. Kelly Courtroom Three Administrative Law Judge, California Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board Law Clerk to Judge Alarcón, 1980 - 1982, 1993 - 1994 RICHARD H. CHAMBERS UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS BUILDING The Honorable Gregory W. Alarcon Superior Court, County of Los Angeles 125 South Grand Avenue Pasadena, California ADJOURNMENT Reception Immediately Following 1925 Born August 14th in Los Angeles, California 1943 - 1946 Staff Sergeant, Army Infantry. Awarded multiple honors for battlefield bravery and leadership 1949 B.A., University of Southern California (USC) 1951 LL.B., USC School of Law Editorial Board Member, USC Law Review 1952 - 1961 Deputy District Attorney, County of Los Angeles 1961 - 1964 Legal Advisor, Clemency/Extradition Secretary and Executive Assistant to Gov. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown 1964 - 1978 Judge, Superior Court, County of Los Angeles 1978 - 1979 Associate Justice, California Court of Appeal 1979 - 2015 First Hispanic judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. -

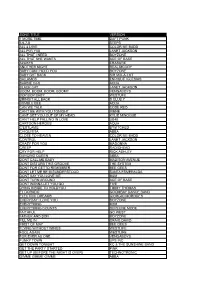

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Kozinski and Banner

TAB 7 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 76 MAY 1990 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES WHO'S AFRAID OF COMMERCIAL SPEECH? Alex Kozinski and Stuart Banner* N 1942, the Supreme Court plucked the commercial speech doc- trine out of thin air. The case was Valentine v. Chrestensen:1 Mr. Chrestensen was a man with a nose for business and a submarine, which he moored in New York's East River and opened to the public for an admission charge. Anticipating substantial wartime interest in viewing the inside of a submarine, he began distributing handbills, but the law caught up with him; a police officer alerted Chrestensen to the fact he was violating section 318 of the Sanitary Code, which prohib- ited the distribution of commercial handbills in public places. Chrestensen was not easily deterred. Mustering the full measure of ingenuity of an entrepreneur who had navigated his submarine all the way from Florida to make a quick buck, he printed two-sided hand- bills. On one side was an advertisement for his submarine; on the other, a protest against the City Dock Department's refusal to permit him to moor the submarine at the pier he preferred. This way, Chrestensen reasoned, the handbill was no longer purely commercial and was thus no longer proscribed by the Sanitary Code. Police Com- missioner Valentine was not amused and prevented Chrestensen from * Alex Kozinski is a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Stuart Banner served as law clerk to Judge Kozinski in 1988-89, the idyllic year when the idea for this Article was hatched. -

Mattel, Inc. V. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 36 Number 3 Symposium: ICANN Governance Article 7 3-1-2003 Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons Tamar Buchakjian Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tamar Buchakjian, Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc.: Let's Party in Barbie's World - Expanding the First Amendment Right to Musical Parody of Cultural Icons, 36 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 1321 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol36/iss3/7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MA TTEL, INC. V. MCA RECORDS, INC.: LET'S PARTY IN BARBIE'S WORLD-EXPANDING THE FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT TO MUSICAL PARODY OF CULTURAL ICONS I. INTRODUCTION On July 24, 2002, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc. -a case that may have a substantial impact on reaching a balance between the interests of trademark owners of cultural icons and the First Amendment rights of musical parodists of those cultural icons. By ruling in favor of the defendants, the Ninth Circuit held that the use of the "Barbie" trademark in a musical parody (1) was not an infringement of the toy manufacturer's trademark associated with the Barbie doll because the song was not likely to confuse the consumer as to its source or sponsorship, and (2) was not actionable under the Federal Trademark 2 Dilution Act (FTDA) as diluting the Barbie trademark3 because the song fell within the noncommercial use exception. -

Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: the Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2017 Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law Jane C. Ginsburg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Jane C. Ginsburg, Intellectual Property As Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law, JOURNAL OF THE COPYRIGHT SOCIETY OF THE USA, VOL. 65, P. 245, 2018; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 14-567 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2072 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [forthcoming, Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA] Intellectual Property as Seen by Barbie and Mickey: The Reciprocal Relationship of Copyright and Trademark Law Jane C. Ginsburg* Abstract Some years ago, caselaw on trademark parodies and similar unauthorized “speech” uses of trademarks could have led one to conclude that the law had no sense of humor. Over time, however, courts in the US and elsewhere began to leaven likelihood of confusion analyses with healthy skepticism regarding consumers’ alleged inability to perceive a joke. These decisions did not always expressly cite the copyright fair use defense, but the considerations underlying the copyright doctrine seemed to inform trademark analysis as well.