Empowering Women Using Community Based Advocacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detestable Offenses: an Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century”

“Detestable Offenses: An Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century” Taylor Runquist Western Illinois University 1 The act of sodomy has a long history of illegality, beginning in England during the reign of Henry VIII in 1533. The view of sodomy as a crime was brought to British America by colonists and was recorded in newspapers and law books alike. Sodomy laws would continue to adapt and change after their initial creation in the colonial era, from a common law offense to a clearly defined criminal act. Sodomy laws were not meant to persecute homosexuals specifically; they were meant to prevent the moral corruption and degradation of society. The definition of homosexuality also continued to adapt and change as the laws changed. Although sodomites had been treated differently in America and England, being a sodomite had the same social effects for the persecuted individual in both countries. The study of homosexuals throughout history is a fairly young field, but those who attempt to study this topic are often faced with the same issues. There are not many historical accounts from homosexuals themselves. This lack of sources can be attributed to their writings being censored, destroyed, or simply not withstanding the test of time. Another problem faced by historians of homosexuality is that a clear identity for homosexuals did not exist until the early 1900s. There are two approaches to trying to handle this lack of identity: the first is to only treat sodomy as an act and not an identity and the other is to attempt to create a homosexual identity for those convicted of sodomy. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. ________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ____________ TIM MOOSE, Petitioner, v. WILLIAM SCOTT MACDONALD, Respondent. ____________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ____________ PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ____________ KENNETH T. CUCCINELLI, II PATRICIA L. WEST Attorney General of Virginia Chief Deputy Attorney General E. DUNCAN GETCHELL, JR. WESLEY G. RUSSELL, JR. Solicitor General of Virginia Deputy Attorney General [email protected] [email protected] Counsel of Record OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MICHAEL H. BRADY 900 East Main Street Assistant Solicitor General Richmond, Virginia 23219 [email protected] Telephone: (804) 786-7240 Facsimile: (804) 371-0200 Counsel for the Petitioner June 25, 2013 i QUESTION PRESENTED In 2003, this Court took up the question “[w]hether Petitioners’ criminal convictions for adult consensual sexual intimacy in the home violate their vital interests in liberty and privacy protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” in the context of a challenge to a Texas statute that prohibited “‘deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex.’” Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 563-64 (2003) (quoting Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 21.06(a) (2003)). This Court answered that question in the affirmative, but stressed what it was not deciding. Id. at 578. “The present case does not involve minors. It does not involve persons who might be injured or coerced or who are situated in relationships where consent might not easily be refused. It does not involve public conduct or prostitution. -

Opinion Filed: September 2, 2020 ) V

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF IDAHO Docket No. 46724 STATE OF IDAHO, ) Boise, May 2020 Term ) Plaintiff-Respondent, ) Opinion Filed: September 2, 2020 ) v. ) Melanie Gagnepain, Clerk ) KLAUS NICO GOMEZ-ALAS ) ) Defendant-Appellant. ) ) Appeal from the District Court of the Fifth Judicial District of the State of Idaho, Blaine County. Ned C. Williamson, District Judge. The decision of the district court is affirmed. Eric D. Fredericksen, State Appellate Public Defender, Boise, for Appellant. Andrea Reynolds argued. Lawrence G. Wasden, Idaho Attorney General, Boise, for Respondent. Kenneth Jorgensen argued. BEVAN, Justice I. NATURE OF THE CASE In December 2017, Klaus Nico Gomez-Alas was charged with two felony counts: rape and infamous crime against nature. At trial, he was acquitted on the first count of rape, but convicted of simple battery as an included offense. On the second count, the jury found Gomez-Alas guilty of an infamous crime against nature. After the verdict, Gomez-Alas moved the district court for a new trial pursuant to Idaho Criminal Rule (I.C.R.) 34, arguing the district court misled the jury by giving an improper “dynamite” instruction. Gomez-Alas also moved the district court for judgment of acquittal on the second count pursuant to I.C.R. 29, arguing there was insufficient evidence to support a conviction for the infamous crime against nature charge. The district court denied both post-trial motions. Gomez-Alas appeals, arguing: (1) the act of cunnilingus does not constitute an infamous crime against nature under Idaho Code sections 18-6605 and 18-6606; (2) there was 1 insufficient evidence to support a conviction for the infamous crime against nature charge; and (3) the district court misled the jury by providing an improper dynamite instruction. -

Depriest V. Commonwealth of Virginia

In the Court of Appeals _f Virginia Appeals from the Circuit Court of the City of Roanoke RECORDNOS. 1587-99-3, 1595-99-3 THROUGH1601-99-3, 1619-99-3, AND1920-99-3 ELVIS GENE DePRIEST, et al., Appellants, Vl COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Appellee. BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE THE LIBERTY PROJECT IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS Julie M. Carpenter VSB No. 30421 Jared O. Freedman Elena N. Broder-Feldman JENNER & BLOCK 601 Thirteenth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 639-6000 Counsel for The Liberty Project BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE THE LIBERTY PROJECT IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICUS ....................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................... 2 QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................................... 4 SUMMARY OF FACTS ........................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................. 4 ARGUMENT ................................................................. 6 I. Section 18.2-361A of the Virginia Code Violates the Fundamental Right to Privacy Implicitly Guaranteed by the Virginia Constitution ................ 6 II. Conviction under Section 18.2-29 of the Virginia Code in This Case Violates the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause of the Eighth Amendment of the United States Constitution and of Article I, Section 9 of the Virginia Constitution ....................................... 11 A. The Gravity of the Offense Does Not Justify the Authorized Penalty and the -

The Constitutionality of Sodomy Statutes

Fordham Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Article 4 1976 The Constitutionality of Sodomy Statutes James J. Rizzo Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation James J. Rizzo, The Constitutionality of Sodomy Statutes, 45 Fordham L. Rev. 553 (1976). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol45/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF SODOMY STATUTES I. INTRODUCTION At the present time private consensual sodomy is a criminal offense in the large majority of our states,' punishable by sentences of up to ten, or even twenty years.2 Such laws raise a number of constitutional issues, the resolu- tion of which will determine whether or not consensual sodomy statutes exceed the limits of the state's police power by violating the constitutionally protected rights of its citizens. These issues include the vagueness and overbreadth of statutory language, the violation of the eighth amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments and of the first amend- ment's establishment clause, and the infringement of the rights of privacy and equal protection. Recently the Supreme Court had the opportunity to address itself to the question of the validity of anti-sodomy legislation. In Doe v. Commonwealth's Attoazeyfor City of Richmond, 3 without opinion and without benefit of full briefing or oral argument, the Court affirmed a decision of a three-judge federal district court,4 in which the Virginia statutes had been held constitu- 1. -

Spears V. State, 337 So. 2D 977 (Fla. 1976)

Florida State University Law Review Volume 6 Issue 2 Article 10 Spring 1978 Spears v. State, 337 So. 2d 977 (Fla. 1976) John Mueller Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation John Mueller, Spears v. State, 337 So. 2d 977 (Fla. 1976), 6 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 531 (1978) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol6/iss2/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASE COMMENT Constitutional Law-SPEECH-FLORIDA'S INDECENT AND OBSCENE LANGUAGE STATUTE DECLARED UNCONSTITUTIONAL ON ITS FACE FOR OVERBREADTH-Spears v. State, 337 So. 2d 977 (Fla. 1976). A Wakulla County Sheriffs deputy answered a disturbance call at Evan's Pool Hall on October 26, 1975. Upon pulling into the area of the pool hall, he heard Blannie Mae Spears cursing "in a loud and angry manner."' He arrested her and charged her with publicly using "indecent or obscene language, to wit: SON OF A BITCH, BASTARD M.F. ETC, [sic] contrary to section 847.05, FLORIDA STATUTES." ' 2 The statute provided: "Any person who shall pub- licly use or utter any indecent or obscene language shall be guilty of a misdemeanor .... ''3 In Wakulla County Court Ms. Spears sought dismissal of the charge on the ground that the statute was an unconstitutional abridgment of the freedom of speech guaranteed by the first and fourteenth amendments to the United States Constitution. -

The Law of Crime Against Nature James R

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 32 | Number 3 Article 2 4-1-1954 The Law of Crime against Nature James R. Spence Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation James R. Spence, The Law of Crime against Nature, 32 N.C. L. Rev. 312 (1954). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol32/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LAW OF CRIME AGAINST NATUREt JAmES R. SPENCE-* I. INTRODUCTION Ever since Dr. Kinsey made public in 1948 his first study of the sexual drives there has been an increased realization among both lay- men and lawyers of the wide gulf between the concepts of law and psychiatry in that realm of criminal behavior represented by what we may broadly term sexual offenses. Within this broad category there is, perhaps, no one specific area which is least understood or more con- fused than that of the so-called "crimes against nature." This article undertakes to look briefly into the legislative and judicial history of that crime in North Carolina and the other states in an effort to ascer- tain the nature of the crime as it exists at present and to discover what could and should be done to bring this limited but important segment of criminal law more in line with the recognized concepts of psychiatry and medical science. -

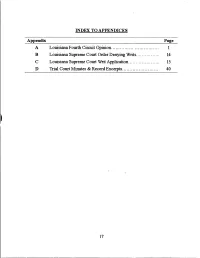

Appendix Page a Louisiana Fourth Circuit Opinion

INDEX TO APPENDICES Appendix Page A Louisiana Fourth Circuit Opinion................... 1 B Louisiana Supreme Court Order Denying Writs 14 C Louisiana Supreme Court Writ Application...... 15 D Trial Court Minutes & Record Excerpts........... 40 17 Office Of The Clerk Court of Appeal, Fourth Circuit Mailing Address: State of Louisiana 410 Royal Street Justin I. Woods New Orleans, Louisiana Clerk of Court 400 Royal Street 70130-2199 Third Floor (504) 412-6001 JoAnn Veal FAX (504) 412-6019 Chief Deputy Clerk of Court NOTICE OF -IUDGMENT AND CERTIFICATE OF MAILING I parties not represented by counsel, as listed below. jiw/rmi JUSTIN I. WOODS CLERK OF COURT 9018-KA-0777 C/W: 2018-K-1024 Michael Danon Nathaniel Lambert #90883 Donna Andrieu Sherry Watters MPEY/SPRUCE - 3 LOUISIANA APPELLATE PROJECT Leon Cannizzaro Louisiana State Prison District Attorney P. O. Box 58769 - Angola, LA 70712- New Orleans. LA 70158- ORLEANS PARISH 619 S. White Street New Orleans. LA 70119- ScottG. Vincent Assistant District Attorney 619 South White Street New Orleans, LA 70119- / STATE OF LOUISIANA NO. 2018-KA-0777 VERSUS COURT OF APPEAL NATHANIEL LAMBERT FOURTH CIRCUIT STATE OF LOUISIANA * * * * * * * CONSOLIDATED WITH: CONSOLIDATED WITH: STATE OF LOUISIANA NO. 2018-K-1024 VERSUS NATHANIEL LAMBERT APPEAL FROM CRIMINAL DISTRICT COURT ORLEANS PARISH NO. 387-752, SECTION “D” Honorable Paul A Bonin, Judge * * * * * * Judge Tiffany G. Chase * # * (Court composed of Judge Daniel L. Dysart, Judge Joy Cossich Lobrano, Judge Tiffany G. Chase) LOBRANO, J. CONCURS IN THE RESULT. Leon Cannizzaro, District Attorney Scott G. Vincent, Assistant District Attorney DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE, ORLEANS PARISH 619 S. -

Impact Statement

Impact Analysis on Proposed Legislation Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission House Bill No. 1054 (Patron –Albo) Date Submitted: 01/12/2004 LD #: 04-0894134 Topic: Non-forcible sodomy & fornication Proposed Change: The proposal repeals § 18.2-344 (fornication), and adds to the Code of Virginia § 18.2-361.1 (carnal knowledge in a public place) and § 18.2-387.1 (carnal knowledge in correctional facilities). Also amended are §§ 15.2-1724, 18.2-345, 18.2-346, 18.2-348, 18.2-356, 18.2-370, 18.2-370.1 and 18.2-371 related to territorial limits for police officers, lewd behavior, prostitution, indecent liberties with children and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. The proposed legislation is, in part, a response to United States Supreme Court’s decision in the Lawrence et al. v. Texas case. The existing statute for crimes against nature, §18.2-361, is not modified by this proposal. Instead a section is added that defines carnal knowledge by anus or mouth in a public place as a Class 6 felony (1-5 years). The proposal adds carnal knowledge (as defined by § 18.2-63) in the definitions for the indecent liberties with children (§§ 18.2-370 and 18.2-370.1) and contributing to the delinquency of a minor (§ 18.2-371.) statutes. A new Class 1 misdemeanor (0-12 months) is added for carnal knowledge in a correctional facility. Prostitution offenses (§§ 18.2-346 & 18.2-348) are amended by the proposal to include the act of carnal knowledge by mouth or anus. -

California Law Review, Inc

Equality with Exceptions? Recovering Lawrence’s Central Holding Anna K. Christensen* In the eleven years since the Supreme Court handed down its Lawrence v. Texas1 ruling, state courts have not consistently adhered to the decision’s implicit rejection of laws that regulate based on animus alone. Relying on the Court’s explicit limitation of its decision to cases that do not involve minors, “persons who might be injured or coerced or who are situated in relationships where consent might not easily be refused,” public conduct, prostitution, government recognition of same-sex relationships, and practices not “common to a homosexual lifestyle”2—the so-called Lawrence exceptions—a number of states have continued to use archaic antisodomy laws to police conduct they see as morally reprehensible. This Comment examines the interpretation and application of the Lawrence exceptions by state courts, arguing that by maintaining discriminatory prosecution and punishment schemes for conduct deemed to fall within the exceptions, states run afoul of the core antidiscriminatory logic of Lawrence and of the Court’s earlier ruling in Romer v. Evans.3 My analysis addresses not only whether laws that fall within the Lawrence exceptions discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation, but also whether they enable or invite discrimination along gender- and race-based lines. Copyright © 2014 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. * J.D., University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, 2014; B.A., Brown University, 2007. Special thanks to Professor Russell Robinson for his generous and insightful feedback throughout the writing process, and to my colleagues at the California Law Review for their thoughtful and thorough edits. -

Criminal Law. Sodomy. Buggery. Infamous Crime. the Infamous Crime Against Nature May Be Committed by Insertion in Any Opening of the Body Except Sexual Parts

264 OPINIONS OF ATTORNEY GENERAL. be made at the expense of the company so that no delay or damage may result in the construction of the highway. In the above I am assuming that the railroad has b'een constructed over public lands prior to the laying out or construction of the highway. If the public highway is already established before the construction of the line of railway or canal crossing it, the rule is different. In that event th'e company would have to, at its own expense, put the road in as good condition as it was before and so maintain it. Se'e Am. Digest, Cent. Ed., Vol. 41, Secs. 284 to 290, and cases there cited. Yours very truly, ALBERT J. GALEN, Attorney General. Criminal Law. Sodomy. Buggery. Infamous Crime. The infamous crime against nature may be committed by insertion in any opening of the body except sexual parts. Helena, Montana, April 29, 1908. Hon. James E. Murray. County Attorney, Butte Montana. Dear 8Ir:- I am in receipt of your l:etter of the 25th inst., submitting a propo sition substanti'ally as follows: "A. carnally abuses a boy by taking his private parts In his mouth; is A. guilty of 'the infamous crime against nature?'" This i's a question that has not been discussed at any great length for the reason, as stated by the supreme court of Wisconsin, courts refuse "to soil the pages of our reports with lengthened discussion of the loathsome subject." Section 496 of th'e Montana Penal Code provides: "Every person who is guilty of the infamous crime against nature, committed with mankind or with any animal, is punish· able," etc. -

7-15Cv00379.Pdf

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA ROANOKE DIVISION GEORGE H. SPIKER, JR., ) ) Petitioner, ) Case No. 7:15CV00379 ) v. ) OPINION ) HAROLD W. CLARKE, ) By: James P. Jones ) United States District Judge Respondent. ) George H. Spiker, Jr., Pro Se Petitioner; John W. Blanton, Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General, Richmond, Virginia, for Respondent. George H. Spiker, Jr., a Virginia inmate, has filed a pro se petition for habeas corpus under 28 U.S.C. § 2254, contending that his 2010 state convictions for computer solicitation of a minor for sexual acts are void. Spiker relies on MacDonald v. Moose, 710 F.3d 154, 156 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 200 (2013). In MacDonald, the Fourth Circuit granted habeas relief to a Virginia inmate who had been convicted of soliciting a minor to commit a felony. The predicate felony charged was MacDonald’s solicitation of a minor to perform oral sex on him, in violation of Virginia’s “Crime Against Nature” statute, Va. Code § 18.2-361(A), which criminalized carnal knowledge “by the anus or by or with the mouth,” commonly known as sodomy. Relying upon Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), which struck down Texas’ anti-sodomy statute as unconstitutional, the Fourth Circuit held that section 18.2-361(A) was facially unconstitutional because by its terms it criminalized sodomy between consenting adults, and thus could not support MacDonald’s solicitation conviction, even though his actual conduct involved a minor. Upon review of the record, I conclude that the respondent’s Motion to Dismiss must be granted, because the habeas petition is untimely, procedurally defaulted, and without merit.