Extralegal Whitewashes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notebooks Esteve Foundation 42

NOTEBOOKS Esteve Foundation 42 Television fiction viewed from the perspective Medicine in Television Series of medical professionals House and Medical Diagnosis. Lisa Sanders Editor: Toni de la Torre The Knick and Surgical Techniques. Leire Losa The Sopranos and Psychoanalysis. Oriol Estrada Rangil The Big Bang Theory and Asperger’s Syndrome. Ramon Cererols Breaking Bad and Methamphetamine Addiction. Patricia Robledo Mad Men and Tobacco Addiction. Joan R. Villalbí The Walking Dead and Epidemics in the Collective Imagination. Josep M. Comelles and Enrique Perdiguero Gil Angels in America, The Normal Heart and Positius: HIV and AIDS in Television Series. Aina Clotet and Marc Clotet, under the supervision of Bonaventura Clotet Nip/Tuck, Grey’s Anatomy and Plastic Surgery. María del Mar Vaquero Pérez Masters of Sex and Sexology. Helena Boadas CSI and Forensic Medicine. Adriana Farré, Marta Torrens, Josep-Eladi Baños and Magí Farré Homeland and the Emotional Sphere. Liana Vehil and Luis Lalucat Series Medicine in Television Olive Kitteridge and Depression. Oriol Estrada Rangil True Detective and the Attraction of Evil. Luis Lalucat and Liana Vehil Polseres vermelles and Cancer. Pere Gascón i Vilaplana ISBN: 978-84-945061-9-2 9 788494 506192 42 NOTEBOOKS OF THE ESTEVE Foundation Nº 42 Mad Men and Tobacco Addiction Joan R. Villalbí Don Draper is, in all likelihood, one of the most representative icons of the golden age that TV series are currently enjoying. Set in a New York ad agency in the 1960s, the show is a true and elegant reflection of a period characterized by social discrimination, and has reaped the most prestigious accolades since it premiered on the cable channel AMC in 2008. -

Women and Work in Mad Men Maria Korhon

“You can’t be a man. Be a woman, it’s a powerful business when done correctly:” Women and Work in Mad Men Maria Korhonen Master’s Thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Spring 2016 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. History of Working Women .................................................................................................................... 5 2. Appearance .................................................................................................................................................. 10 2.1. Appearance bias ................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1 Weight ................................................................................................................................................ 12 2.1.2. Beauty ideals ..................................................................................................................................... 15 2.1.3. 1960s Work Attire ............................................................................................................................. 18 2.1.4. Clothing and external image in the workplace .................................................................................. 20 2.1.5. Gender and clothing ......................................................................................................................... -

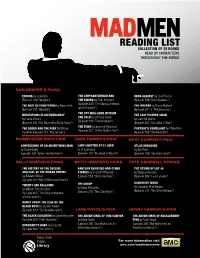

Reading List Collection of 25 Books Read by Characters Throughout the Series

READING LIST COLLECTION OF 25 BOOKS READ BY CHARACTERS THROUGHOUT THE SERIES DON DRAPER’S PICKS EXODUS by Leon Uris THE CHRYSANTHEMUM AND ODDS AGAINST by Dick Francis (Episode 106 “Babylon”) THE SWORD by Ruth Benedict (Episode 509 “Dark Shadows”) (Episode 405 “The Chrysanthemum THE BEST OF EVERYTHING by Rona Jaffe THE INFERNO by Dante Alighieri and the Sword”) (Episode 106 “Babylon”) (Episode 601-2 “The Doorway”) THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM MEDITATIONS IN AN EMERGENCY THE LAST PICTURE SHOW by John Le Carre by Frank O’Hara THE COLD by Larry McMurtry (Episode 413 “Tomorrowland”) (Episode 201 “For Those Who Think Young”) (Episode 607 “Man With a Plan”) THE FIXER by Bernard Malamud THE SOUND AND THE FURY by William PORTNOY’S COMPLAINT by Philip Roth (Episode 507 “At the Codfish Ball”) Faulkner (Episode 211 “The Jet Set”) (Episode 704 “The Monolith”) ROGER STERLING’S PICK JOAN HARRIS’S PICK BERT COOPER’S PICK CONFESSIONS OF AN ADVERTISING MAN LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER ATLAS SHRUGGED by David Ogilvy D. H. Lawrence by Ayn Rand (Episode 307 “Seven Twenty Three”) (Episode 103 "Marriage of Figaro") (Episode 108 “The Hobo Code”) SALLY DRAPER’S PICKS BETTY DRAPER’S PICKS PETE CAMPBELL’S PICKS THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE BABYLON REVISITED AND OTHER THE CRYING OF LOT 49 AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE STORIES by F. Scott Fitzgerald by Thomas Pynchon by Edward Gibbon (Episode 204 “Three Sundays”) (Episode 508 “Lady Lazarus”) (Episode 303 “My Old Kentucky Home”) GOODNIGHT MOON TWENTY ONE BALLOONS THE GROUP by Mary McCarthy by Margaret Wise Brown by William Pene -

ENG 1131: Writing About American Prestige TV (Sec 4841)

ENG 1131: Writing About American Prestige TV (sec 4841) Milt Moise MWF/R: Period 4: 10:40-11:30; E1-E3: 7:20-10:10 Classroom: WEIL 408E Office Hours: W, R Per. 7-8, or by appointment, TUR 4342 Course Website: CANVAS Instructor Email: [email protected] Twitter account: @milt_moise Course Description, Objectives, and Outcomes: This course examines the emergence of what is now called “prestige TV,” and the discourse surrounding it. Former FCC chairman Newton N. Minow, in a 1961 speech, once called TV “a vast wasteland” of violence, formulaic entertainment, and commercials. Television has come a long way since then, and critics such as Andy Greenwald now call our current moment of television production “the golden age of TV.” While television shows containing the elements Minow decried decades ago still exist, alongside them we now find television characterized by complex plots, moral ambiguity, excellent production value, and outstanding writing and acting performances. In this class, our discussions will center around, but not be limited to the aesthetics of prestige TV, and how AMC’s Mad Men and TBS’s Search Party conform to or subvert this framework. Students will learn to visually analyze a television show, and develop their critical reading and writing skills. By the end of the semester, students will be able to make substantiated arguments about the television show they have seen, and place it into greater social and historical context. They will also learn how to conduct formal research through the use of secondary sources and other relevant material to support their theses, analyses and arguments. -

THE CIRCUITRY of MEMORY: TIME and SPACE in MAD MEN by Molly Elizabeth Lewis B.A., Honours, the University of British Columbia, 2

THE CIRCUITRY OF MEMORY: TIME AND SPACE IN MAD MEN by Molly Elizabeth Lewis B.A., Honours, The University of British Columbia, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 © Molly Elizabeth Lewis, 2015 Abstract Memory is central to Mad Men (Matthew Weiner 2007-15) as a period piece set in the 1960s that activates the memories of its viewers while also depicting the subjective memory processes of its protagonist Donald Draper (Jon Hamm). Narratively, as much as Don may try to move forward and forget his past, he ultimately cannot because the memories will always remain. Utilizing the philosophy of Henri Bergson, I reveal that the series effectively renders Bergson’s notion of the coexistence of past and present in sequences that journey into the past without ever leaving the present. Mad Men ushers in a new era of philosophical television that is not just perceived, but also remembered. As a long-form serial narrative that intricately layers past upon present, Mad Men is itself an evolving memory that can be revisited by the viewer who gains new insight upon each viewing. Mad Men is the ideal intersection of Bergson’s philosophy of the mind and memory and Gilles Deleuze’s cinematic philosophy of time. The first chapter simply titled “Time,” examines the series’ first flashback sequence from the episode “Babylon,” in it finding the Deleuzian time- image. The last chapter “Space,” seeks to identify the spatial structure of the series as a whole and how it relates to its slow-burning pace. -

{PDF EPUB} Suburban Secrets a Neighborhood of Nightmares by John Ledger Jimgoforthhorrorauthor

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Suburban Secrets A Neighborhood of Nightmares by John Ledger jimgoforthhorrorauthor. TALES FROM THE LAKE VOL. 2, UNDEAD FLESHCRAVE AND OTHER UPDATES. TALES FROM THE LAKE VOL. 2, UNDEAD FLESHCRAVE AND OTHER UPDATES. This poor old WordPress site gets sadly neglected a lot of the time, but on top of running my author page on Facebook, along with pages for WetWorks, Rejected For Content and Plebs, as well as maintaining a Twitter, Google+, Goodreads and miscellaneous other accounts, it’s probably lucky it gets the attention it does. At least it isn’t anything like my BookLikes and AuthorsDen pages. Fuck all happens there with those. In any event, I figured a little update or two on where I’m at, what projects are in the works, what next to expect from me and all that sort of thing was probably in order. Firstly, the next thing folks can expect from me is an appearance in Volume 2 of Tales From the Lake from one of my very favourite publishing houses around, Crystal Lake Publishing. This is slated for release in late August, and though I’m not sure whether that is set in stone or if it’s had to be pushed back at all, it should still be appearing in the very near future. I’m supremely excited about this one for a multitude of reasons. Most folks are probably well aware that I’m a massive Richard Laymon aficionado-the great man is my biggest influence and inspiration-and while he would be top of my list of authors I’d love to have shared a TOC with, there are a host of other names that are right up there too, notably Edward Lee and Jack Ketchum. -

Remembering Through Retro TV and Cinema: Mad Men As Televisual Memorial to 60S America

COPAS—Current Objectives of Postgraduate American Studies 15.1 (2014) Remembering through Retro TV and Cinema: Mad Men as Televisual Memorial to 60s America Debarchana Baruah ABSTRACT: This article examines ways in which some contemporary American television and cin- ema set in the 1950s and 1960s such as Pleasantville and Mad Men share a critical engagement with the period they represent. The engagement is throuGh the twin processes of identification and dissonance. The article describes this way of reviewinG the past as retro representation. The article further explores the idea of retros as televisual memorials for the present, as they con- tribute to preserving memories of the represented period. Mad Men is examined as such a tele- visual memorial of the 60s. KEYWORDS: Retro TV & Cinema, Cultural Memory, Mad Men, Televisual Memorial, Post-War America In America, the past two decades saw an unprecedented rise in television and cinema pro- ductions that are set in the past. Many of these cluster around the post-war period, particu- larly around the 1950s and 1960s. In this article, I explore reasons for revisitinG the period in television and cinema, and the contribution of these contemporary televisual representa- tions to rememberinG the period. In doing so, I use the concept of the retro1 to describe a particular way in which some contemporary American TV and cinema enGage with the post- war period, stokinG Generational anxiety surrounding this period in the present. I define ret- ro as a process of re-viewinG a past from the present, motivated less by nostalGia2 or senti- 1 EtymoloGically, “retro” has been used in EnGlish for more than five hundred years, and can be traced to the Latin preposition retro, which indicates “backwards” or “behind.” Perhaps “retrospect” is the most common word in this reGard and was first used ca. -

Formation of an African American Lucumi Religious Subjectivity

"I Worship Black Gods": Formation of an African American Lucumi Religious Subjectivity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Norman, Lisanne. 2015. "I Worship Black Gods": Formation of an African American Lucumi Religious Subjectivity. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467218 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “I Worship Black Gods”: Formation of an African American Lucumi Religious Subjectivity A dissertation presented by Lisanne C. Norman to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2015 © 2015 Lisanne C. Norman All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jacob Olupona Lisanne C. Norman “I Worship Black Gods”: Formation of an African American Lucumi Religious Subjectivity Abstract In 1959, Christopher Oliana and Walter “Serge” King took a historic journey to pre-revolutionary Cuba that would change the religious trajectory of numerous African Americans, particularly in New York City. They became the first African American -

2012 Year in Review

2012 Year In Review A supplement to help you complete the “What Life was Like…” and “Profile of…” Time Capsule books We suggest you use this Year In Review as a guide to help complete the book. You should copy the information into your book using your own handwriting so that the book looks uniform and complete. TOP 10 Songs TOP 10 TV SHOWS 1. Usher, “Climax” 1. Louie, “Daddy’s Girlfriend, Parts 1 and 2? 2. PSY, "Gangnam Style" 2. Community, "Digital Estate Planning" 3. Carly Rae Jepsen, "Call Me Maybe" 3. Game of Thrones, "Blackwater" 4. Taylor Swift, "We Are Never Ever Getting Back 4. Homeland, "Q&A" Together" 5. Girls, "The Return" 5. Parquet Courts, "Master of My Craft" 6. Parks and Recreation, "The Comeback Kid" 6. Skrillex, "Bangarang" 7. Mad Men, "At the Codfish Ball" 7. Nicki Minaj, "Roman in Moscow" 8. The Good Wife, "Another Ham Sandwich" 8. Pussy Riot, "Putin Lights Up the Fires" 9. Awake, Pilot 9. The Belle Brigade, "No Time to Think" 10. Breaking Bad, "Fifty-One" 10. Can, "Graublau" Source: time .com Source: time.com TOP 10 BOX OFFICE MOVIES TOP 10 MOVIE PERFORMERS 1. Amour 1. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva 2. Beasts of the Southern Wild as Georges and Anne in Amour 3. Life of Pi 2. Quvenzhané Wallis as Hushpuppy in Beasts of 4. Anna Karenina the Southern Wild 5. The Dark Knight Rises 3. Clarke Peters as Da Good Bishop Enoch Rouse 6. Zero Dark Thirty in Red Hook Summer 7. Dark Horse 4. Rachel Weisz as Hester Collyer in The Deep 8. -

Jack Kerouac - Big Sur

Jack Kerouac - Big Sur Big Sur, Unmistakably Autobiographical, Big Sur, Jack Kerouac's Ninth Novel, Was Written As The "king Of The Beats" Was Ap-, Proaching Middle-age And Re flects His Struggle To Come To Terms With His Own Myth. The Magnificent And Moving Story. Of jack duluoz, a man blessed by great talent and cursed with an urge towards self- destruction, big sur is at once ker Unmistakably autobiographical, Big Sur, Jack Kerouac's ninth novel, was written as the "King of the beats" was approaching middle-age and reflects his struggle to come to terms with his own myth. The magnificent and moving story. Of jack duluoz, a man blessed by great talent and cursed with an urge towards self-destruction, big sur is at once kerouac's toughest and his most humane work. JACK KEROUAC was born in 1922 in Lowell, Massachusetts, the youngest of three children in a French-Canadian family. In high school he was a star player on the local football team, and went on to win football scholarships to Horace Mann (a New York prep school) and Columbia College. He left Columbia and football in his sophomore year, joined the Merchant Marines and began the restless wanderings that were to continue for the greater part of his life. His first novel, The Town and the City, was published in 1950. On the Road, although written in 1951 (in a few hectic days on a scroll of newsprint), was not published until 1957 -- it made him one of the most controversial and bestknown writers of his time. -

Representations of Traumatic Parent-Child Relationships in Mad Men

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 4-12-2021 Mad Men, Troubled Mothers, and Scarred Children: Representations of Traumatic Parent-Child Relationships in Mad Men Katarina Dulude Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dulude, Katarina, "Mad Men, Troubled Mothers, and Scarred Children: Representations of Traumatic Parent-Child Relationships in Mad Men" (2021). Honors Projects Overview. 187. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/187 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAD MEN, TROUBLED MOTHERS, AND SCARRED CHILDREN: REPRESENTATIONS OF TRAUMATIC PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIPS IN MAD MEN By Katarina Dulude An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors In The Department of English Dulude 2 Introduction In the fourth episode of the last season of the critically acclaimed series Mad Men, one of the protagonists, Roger, is forced to track down his daughter Margaret after she abandons her husband and her young child. He finds her in a commune, and he puts on a good show to appear more accepting than her mother, but the following day he insists she return home. She refuses. He tells her, “I know everyone your age is running away and screwing around, but you can’t, you’re a mother,” and when she still refuses, he picks her up and tries to carry her towards a truck as she struggles in his arms and demands he let her go. -

Pontifícia Universidade Católica Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad Men: Uma história cultural da Publicidade Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- graduação em Comunicação Social do Departamento de Comunicação da PUC-Rio. Orientador: Prof. Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha Rio de Janeiro, Setembro de 2016 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad Men: Uma história cultural da Publicidade Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação Social do Departamento de Comunicação Social do Centro de Ciências Sociais da PUC-Rio. Aprovada pela Comissão Examinadora abaixo assinada. Prof. Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha Orientador Departamento de Comunicação Social - PUC-Rio Profa. Lígia Campos de Cerqueira Lana Departamento de Comunicação Social - PUC-Rio Prof. Guilherme Nery Atem Departamento de Ciências Sociais - PUC-Rio Prof.ª Mônica Herz Vice-Decana de Pós-Graduação do CCS Rio de Janeiro, 23 de setembro de 2016 Todos os direitos reservados. É proibida a reprodução total ou parcial do trabalho sem autorização da universidade, da autora e do orientador. Mariana Ayres Tavares Graduou-se em Comunicação Social, com habilitação em Publicidade, na Universidade Federal Fluminense em 2012. Cursou especialização em Pesquisa de Mercado e Opinião Pública na Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, em 2014. Ficha Catalográfica Tavares, Mariana Ayres Mad Men : uma história cultural da publicida- de / Mariana Ayres Tavares Vasconcelos ; orien- tadora: Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha. – 2016. 118 f. : il. color. ; 30 cm Dissertação (mestrado)–Pontifícia Universi- dade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Comunicação Social, 2016.