Women and Work in Mad Men Maria Korhon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad Men Is MEN MAD MEN Unquestionably One of the Most Stylish, Sexy, and Irresistible Shows on Television

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN EDITED BY Is DON DRAPER a good man? ROD CARVETH AND JAMES B. SOUTH What do PEGGY, BETTY, and JOAN teach us about gender equality? What are the ethics of advertising—or is that a contradiction in terms? M Is ROGER STERLING an existential hero? AD We’re better people than we were in the sixties, right? With its swirling cigarette smoke, martini lunches, skinny ties, and tight pencil skirts, Mad Men is MEN MAD MEN unquestionably one of the most stylish, sexy, and irresistible shows on television. But the series and PHILOSOPHY becomes even more absorbing once you dig deeper into its portrayal of the changing social and political mores of 1960s America and explore the philosophical complexities of its key Nothing Is as It Seems characters and themes. From Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to John Kenneth Galbraith, Milton and Friedman, and Ayn Rand, Mad Men and Philosophy brings the thinking of some of history’s most powerful minds to bear on the world of Don Draper and the Sterling Cooper ad agency. You’ll PHILOSOPHY gain insights into a host of compelling Mad Men questions and issues, including happiness, freedom, authenticity, feminism, Don Draper’s identity, and more—and have lots to talk about the next time you fi nd yourself around the water cooler. ROD CARVETH is an assistant professor in the Department of Communications Media at Fitchburg State College. Nothing Is as It Seems Nothing Is as JAMES B. SOUTH is chair of the Philosophy Department at Marquette University. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Mad Men: Dream Come True TV, edited by Gary R. Edgerton Author(s) Power, Aidan Editor(s) Murphy, Ian Publication date 2013 Original citation Power, A. (2013) Mad Men: Dream Come True TV, edited by Gary R. Edgerton. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 5. doi: 10.33178/alpha.5.11 Type of publication Review Link to publisher's http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue5/HTML/ReviewPower.html version http://dx.doi.org/10.33178/alpha.5.11 Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, The Author(s) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/5784 from Downloaded on 2021-10-05T21:21:09Z 1 Mad Men: Dream Come True TV. Ed. Gary R. Edgerton. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011 (258 pages). ISBN: 978-1848853799 (pb). A Review by Aidan Power, Universität Bremen In Changing Places, the first instalment of David Lodge’s timeless campus trilogy, Morris Zapp, Professor of English at Euphoria College and doyen of Jane Austen studies, announces his intention to write the definitive examination of the author’s work, a towering analysis, exhaustive in scope, that would: examine the novels from every conceivable angle, historical, biographical, rhetorical, mythical, Freudian, Jungian, existentialist, Marxist, structuralist, Christian-allegorical, ethical, exponential, linguistic, phenomenological, archetypal, you name it; so that when each commentary was written there would be simply nothing further to say about the novel in question. -

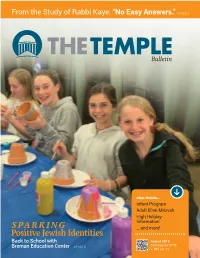

From the Study of Rabbi Kaye: “No Easy Answers.”»PAGE 3

From the Study of Rabbi Kaye: “No Easy Answers.” » PAGE 3 also inside… Infant Program Adult B’nei Mitzvah High Holiday Information SPARKING … and more! Positive Jewish Identities Back to School with August 2019 Tammuz-Av 5779 Breman Education Center » PAGE 6 v. 80 | no. 11 1589 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta, GA 30309 404.873.1731 | Fax: 404.873.5529 the-temple.org | [email protected] Follow us! SCHEDULE: AUGUST 2019 thetempleatlanta @the_templeatl FRIDAY, AUGUST 2 7:30 PM Reform Movement Shabbat Kehillat Chaim, 1145 Green St., Roswell, GA 30075 NO SERVICES AT TEMPLE * LEADERSHIP&STAFF SATURDAY, AUGUST 3 9:00 AM Torah Study Clergy 10:30 AM Chapel Worship Service Rabbi Peter S. Berg, Lynne & Howard Halpern Senior Rabbinic Chair FRIDAY, AUGUST 9 Rabbi Loren Filson Lapidus 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service Rabbi Samuel C. Kaye 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 Cantor Deborah L. Hartman Rabbi Steven H. Rau, RJE, Director of Lifelong Learning SATURDAY, AUGUST 10 Rabbi Lydia Medwin, Director of Congregational 9:00 AM Torah Study Engagement & Outreach 9:30 AM Mini Shabbat Rabbi Alvin M. Sugarman, Ph.D., Emeritus 10:30 AM Bat Mitzvah of Arden Aczel Officers of the Board FRIDAY AUGUST 16 Janet Lavine, President 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service Kent Alexander, Executive Vice President 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 Stacy Hyken, Vice President Louis Lettes, Vice President SATURDAY, AUGUST 17 Eric Vayle, Secretary 9:00 AM Torah Study Jeff Belkin, Treasurer 10:30 AM Chapel Shabbat Worship Service Janet Dortch, Executive Committee Appointee FRIDAY, AUGUST 23 Martin Maslia, Executive Committee Appointee Billy Bauman, Lynne and Howard Halpern Endowment 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service with House Band Fund Board Chair 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 8:00 PM The Well Leadership Mark R. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

The John C. Hench Division of Animation & Digital Arts Students; and Emmy Award Nomination

cinema.usc.edu STATISTICS AT A GLANCE Programs and Degrees Granted Undergraduate Student Body: 912 The mission of the Male: 54 percent Female: 46 percent The Bryan Singer Division of Critical Studies Ethnicity: Bachelor of Arts, Master of Arts, Ph.D. USC School of Cinematic Arts Asian/Pacific Islander: 19 percent Black/African American: 4 percent Film & Television Production Hispanic: 12 percent Bachelor of Fine Arts, Bachelor of Arts, is to develop and articulate Native American/Alaskan: 1 percent Master of Fine Arts Non-Resident Alien: 1 percent John C. Hench Division of Animation & Digital Arts White/Caucasian: 58 percent the creative, scholarly and Bachelor of Arts, Master of Fine Arts Unknown/Other: 4 percent Interactive Media & Games Division Graduate Student Body: 693 entrepreneurial principles and Bachelor of Arts, Master of Fine Arts Male: 54 percent Female: 46 percent Media Arts + Practice Bachelor of Arts, Ph.D. practices of film, television Ethnicity: Asian/Pacific Islander: 10 percent Peter Stark Producing Program Black/African American: 9 percent Master of Fine Arts and interactive media, and in Hispanic: 10 percent Native American/Alaskan: 1 percent Writing for Screen & Television Non-Resident Alien: 23 percent Bachelor of Fine Arts, Master of Fine Arts doing so, inspire and prepare White/Caucasian: 43 percent Unknown/Other: 6 percent Undergraduate Minors the women and men who will Faculty: Animation & Digital Arts Full-time: 96 Cinematic Arts Part-time: 219 Cinema-Television for Health Professionals becomes leaders in the field. Staff: Digital Studies Full-time employees: 144 Game Studies Student workers: 499 Game Animation Living Alumni: over 12,000 Game Audio (Number rounded to the nearest 100) Game Design cinema.usc.edu Game Entrepreneurism Game User Research Science Visualization Screenwriting SCA PHILOSOPHY SCA LOCATION SCA LOcatION SCA FacULTY The School of Cinematic Arts is in the heart of Los Angeles, Each SCA faculty member has worked, or is currently SCA PHILOSOPHY considered the entertainment capital of the world. -

Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism Deborah Tudor [email protected], [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Neoliberalism and Media Global Media Research Center Spring 2012 Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism Deborah Tudor [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gmrc_nm A much earlier version of this project was published in Society, May 2012. This version expands upon the issues of individualism under neoliberalism through an examination of ways that the protagonist portrays a neoliberal subjectivity. Recommended Citation Tudor, Deborah, "Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism" (2012). Neoliberalism and Media. Paper 4. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gmrc_nm/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Global Media Research Center at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Neoliberalism and Media by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men , Postmodernism and Neoliberalism Deborah Tudor Fredric Jameson identified postmodernism as the “cultural logic of late capitalism” in his 1984 essay of the same name. Late capitalism, or neoliberalism, produces a society characterized by return to free market principles of the 19 th century and cultivates a strong return to rugged individualism. (Kapur) Postmodern cultural logic emphasizes visual representations of culture as a dominant cultural determinant. It is this framework that opens a discussion of Mad Men, a series that uses a mid century advertising firm as a filter for a history that is reduced to recirculated images. In Norman Denzin’s discussion of film and postmodernism, he examines how our media culture’s embodies neoliberal, postmodern notions of life and self. -

The Betty Draper Effect

ADVERTISEMENT Babble LIFESTYLE PARENTING FOOD BODY & MIND ENTERTAINMENT BLOGGERS The Betty Draper Effect. BY MELISSA RAYWORTH | POSTED 5 YEARS AGO Share 0 Tweet 0 Share 0 It was just before midnight on a Sunday last fall. I stood rinsing dishes, surrounded by cabinets hung when Lady Bird Johnson lived in the White House. Inside them, melamine dishes in a distinctly mid-century shade of powder blue sat stacked in perfect rows. Behind me, tucked in a thicket of cookbooks, were recipes clipped for dinner parties where the main topic of conversation was the Beatles appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show. I caught my reflection in the kitchen window, my face clearly outlined against the blackness of a suburban night. It wasn’t 1964. But here in this house, for a moment, it was hard to tell. I had spent the past hour watching Mad Men, the AMC show praised for bringing the early ADVERTISEMENT Sixties, in all their sleek but stifled glory, palpably to life. But most viewers, when they clicked off their televisions, returned seamlessly to their twenty-first-century lives. Not me. Featured Articles I’m living in a suburban split-level that has hardly changed since my in-laws built it in 1964. Now unable to manage alone, they moved to a retirement home and left most everything behind. My husband and I have become stewards of a home that is, in many ways, frozen in the Mad Men era. I fell in love with the show immediately, drawn to the way it explores the lives of women on the precipice of ’60s feminism. -

Mr. Spock, Don Draper and the Undoing Project – Lessons for Investment Managers and Asset Allocators

August 2017 Mr. Spock, Don Draper and The Undoing Project – Lessons for Investment Managers and Asset Allocators TINA BYLES WILLIAMS CIO & CEO but are susceptible to certain biases. They then spent 30 plus years researching these biases through both thoughtfulness and experimentation which ultimately led to the development of a new field called Behavioral Economics. Lewis chronicles their journey brilliantly by detailing the duo’s work, relationship and thinking. One interesting aspect of the story is that economists did not wel- Michael Lewis’s latest book, The Undoing Project, tells the story come the new school of thought with open arms. Rather, they of Daniel Khanneman and Amos Tversky, two Israeli psycholo- defended their rationality assumptions so that the foundation of gists who studied how people make decisions and in the pro- their models would not be undone. However, Khanneman and cess changed the way many economists think. As good deci- Tversky were persistent in their quest, designing experiments sion making is at the core of good investment management, we to test their theories. Their experiments were built around un- thought it useful to spend some time on the topic, and hopefully derstanding why people made specific decisions. They gave in the process, shed some light on how good investment man- people problems to solve or choices to make and found that agers make decisions. people more often did not make the optimal or rational choice. What Khaneman and Tversky’s work showed was that humans’ First some background. Prior to Khanneman and Tversky the decision making process was fallible. -

The Cross-Country/Cross-Class Drives of Don Draper/Dick Whitman: Examining Mad Men’S Hobo Narrative

Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 2 Issue 1, 2017 Forsberg The Cross-Country/Cross-Class Drives of Don Draper/Dick Whitman: Examining Mad Men’s Hobo Narrative Jennifer Hagen Forsberg, Clemson University Abstract This article examines how the critically acclaimed television show Mad Men (2007- 2015) sells romanticized working-class representations to middle-class audiences, including contemporary cable subscribers. The television drama’s lead protagonist, Don Draper, exhibits class performatively in his assumed identity as a Madison Avenue ad executive, which is in constant conflict with his hobo-driven born identity of Dick Whitman. To fully examine Draper/Whitman’s cross-class tensions, I draw on the American literary form of the hobo narrative, which issues agency to the hobo figure but overlooks the material conditions of homelessness. I argue that the hobo narrative becomes a predominant but overlooked aspect of Mad Men’s period presentation, specifically one that is used as a technique for self-making and self- marketing white masculinity in twenty-first century U.S. cultural productions. Keywords Cross-class tensions; television; working-class representations The critically acclaimed television drama Mad Men (2007-2015) ended its seventh and final season in May 2015. The series covered the cultural and historical period of March 1960 to November 1970, and followed advertising executive Don Draper and his colleagues on Madison Avenue in New York City. As a text that shows the political dynamism of the mid-century to a twenty-first century audience, Mad Men has wide-ranging interpretations across critical camps. For example, in ‘Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism,’ Deborah Tudor suggests that the show offers commitments to individualism through a ‘neoliberal discourse of style’ which stages provocative constructions of reality (2012, p. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick,