1 All Rights Reserved Do Not Reproduce in Any Form Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Time to Weave, a Time to Remember

LZK-5 SOUTH ASIA Leena Z. Khan is an Institute Fellow studying the intersection of culture, cus- ICWA toms, law and women’s lives in Pakistan. LETTERS A Time to Weave, A Time to Remember Since 1925 the Institute of By Leena Z. Khan Current World Affairs (the Crane- NOVEMBER, 2001 Rogers Foundation) has provided LANDHI, Pakistan–The first time I met Kausar she had just completed weaving long-term fellowships to enable 20 yards of khaddar, or hand-spun cotton fabric. With proud satisfaction, she showed outstanding young professionals me the bright blue-and-orange woven cloth. “It took me only one day to weave to live outside the United States this,” she said, beaming. Kausar is among a handful of khaddar weavers still using and write about international the traditional khaddi, or areas and issues. An exempt handloom.1 operating foundation endowed by the late Charles R. Crane, the Kausar was born in Institute is also supported by Landhi, a dusty and bumpy contributions from like-minded 30-minute drive east of individuals and foundations. Karachi. Landhi, an indus- trial township founded shortly after Partition,2 is in- habited primarily by low-in- TRUSTEES come families. The township Joseph Battat faces a number of festering Mary Lynne Bird problems, from substandard Steven Butler housing and sanitation, to William F. Foote poor health facilities, to con- Kitty Hempstone stant power failures. Kausar Pramila Jayapal has lived in Landhi her en- Peter Bird Martin tire life. I had the pleasure of Ann Mische meeting with her on several Dasa Obereigner occasions. -

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Download Article

Pakistan’s ‘Mainstreaming’ Jihadis Vinay Kaura, Aparna Pande The emergence of the religious right-wing as a formidable political force in Pakistan seems to be an outcome of direct and indirect patron- age of the dominant military over the years. Ever since the creation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1947, the military establishment has formed a quasi alliance with the conservative religious elements who define a strongly Islamic identity for the country. The alliance has provided Islamism with regional perspectives and encouraged it to exploit the concept of jihad. This trend found its most obvious man- ifestation through the Afghan War. Due to the centrality of Islam in Pakistan’s national identity, secular leaders and groups find it extreme- ly difficult to create a national consensus against groups that describe themselves as soldiers of Islam. Using two case studies, the article ar- gues that political survival of both the military and the radical Islamist parties is based on their tacit understanding. It contends that without de-radicalisation of jihadis, the efforts to ‘mainstream’ them through the electoral process have huge implications for Pakistan’s political sys- tem as well as for prospects of regional peace. Keywords: Islamist, Jihadist, Red Mosque, Taliban, blasphemy, ISI, TLP, Musharraf, Afghanistan Introduction In the last two decades, the relationship between the Islamic faith and political power has emerged as an interesting field of political anal- ysis. Particularly after the revival of the Taliban and the rise of ISIS, Author. Article. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 14, no. 4: 51–73. -

Cyclone Contigency Plan for Karachi City 2008

Cyclone Contingency Plan for Karachi City 2008 National Disaster Management Authority Government of Pakistan July 2008 ii Contents Acronyms………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..iii Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………....iv General…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Aim………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Scope…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Tropical Cyclone………………………………………………………………………………………..……………….2 Case Studies Major Cyclones………………………..……………………………………… ……………………….3 Historical Perspective – Cyclone Occurrences in Pakistan…...……………………………………….................6 General Information - Karachi ….………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Existing Disaster Response Structure – Karachi………………………. ……………………….…………….……8 Scenarios for Tropical Cyclone Impact in Karachi City ……………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 1 ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 2. ……………………………………………………………………………………………….….13 Response Scenario -1…………………… ……………………………………………………………………….…..14 Planning Assumptions……………………………………………………………………………………....14 Outline Plan……………………………………………………………………………………………….….15 Pre-response Phase…………………………………………………………………………………….… 16 Mid Term Measures……………………………………………………………………..………..16 Long Term Measures…………………...…………………….…………………………..……...20 Response Phase………… ………………………..………………………………………………..………21 Provision of Early Warning……………………. ......……………………………………..……21 Execution……………………….………………………………..………………..……………....22 Health Response……………….. ……………………………………………..………………..24 Coordination Aspects…………………………………………….………………………...………………25 -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

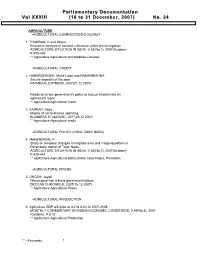

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

Profile: Health and Demographic Surveillance System in Peri-Urban

Gates Open Research Gates Open Research 2018, 2:2 Last updated: 14 JUL 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Profile: Health and Demographic Surveillance System in peri- urban areas of Karachi, Pakistan [version 1; peer review: 1 approved with reservations, 2 not approved] Muhammad Ilyas 1, Komal Naeem1, Urooj Fatima1, Muhammad Imran Nisar 1, Abdul Momin Kazi1, Fyezah Jehan 1, Yasir Shafiq1, Usma Mehmood1, Rashid Ali1, Murtaza Ali1, Imran Ahmed1, Anita K.M. Zaidi1,2 1Department of Paediatrics & Child Health, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan 2Enteric and Diarrheal Diseases Programme, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, 98109, USA v1 First published: 04 Jan 2018, 2:2 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.12788.1 Latest published: 04 Jan 2018, 2:2 https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.12788.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract The Aga Khan University’s Health and Demographic Surveillance 1 2 3 System (HDSS) in peri urban areas of Karachi was set up in the year 2003 in four low socioeconomic communities and covers an area of version 1 17.6 square kilometres. Its main purpose has been to provide a 04 Jan 2018 report report report platform for research projects with the focus on maternal and child health improvement, as well as educational opportunities for trainees. 1. Daniel D. Reidpath , Monash University The total population currently under surveillance is 249,128, for which a record of births, deaths, pregnancies and migration events is Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia maintained by two monthly household visits. Verbal autopsies for Hyi-Yenn Thoo, Monash University Malaysia, stillbirths, deaths of children under the age of five years and adult Selangor, Malaysia female deaths are conducted. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Construction and Rehabilitation of National Highway N-5 in Karachi City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan Karachi Metropolitan Corporation PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY N-5 IN KARACHI CITY IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN JANUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INGÉROSEC CORPORATION EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. EI JR 17-0 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the consortium of INGÉROSEC Corporation and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan and the explanation of survey result in Pakistan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. January, 2017 Akira Nakamura Director General, Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY (1) Outline of the Country The Islamic Republic of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as Pakistan) is a large country in the South Asia having land of 796 thousand km2 that is almost double of Japan and 177 million populations that is 6th in the world. In 2050, the population in Pakistan is expected to exceed Brazil and Indonesia and to be 335 million which is 4th in the world. -

Extremism and Terrorism

Pakistan: Extremism and Terrorism On April 21, 2021, a car bomb exploded in the parking lot of the Serena Hotel in Quetta, killing at least five and wounding 11. Chinese ambassador to Pakistan Nong Rong was staying in the hotel but was not present during the attack. Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed responsibility. “It was a suicide attack in which our suicide bomber used his explosives-filled car in the hotel,” the TTP said in a text message to Reuters. (Sources: Reuters, Associated Press) On April 12, 2021, police in Lahore arrested Saad Rizvi, leader of the outlawed Islamist political party Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP). The arrest was reportedly to deter TLP supporters from further demanding the expulsion of France’s ambassador over the publication in France of cartoons featuring Islam’s Prophet Muhammad. Rizvi had claimed the government had reached an agreement with his party to expel the ambassador by April 20, while government officials claimed they agreed only to discuss the issue in parliament. In response to Rizvi’s arrest, TLP supporters blocked highways and clash with police across the country over the course of two days, killing at least four people and wounding dozens of others, including at least 60 police officers. On April 18, TLP supporters attacked a police station in Lahore while rallying in the city against Rizvi’s arrest. The protesters took hostage 11 officers. The protesters released the hostages the following day after negotiations with the government. Photos released of the hostages during the negotiations showed they had been tortured. (Sources: Voice of America, Associated Press) Overview Since its independence from British colonial rule in 1947, Pakistan has been divided along ethnic, religious, and sectarian lines, a condition which has been exploited by internal and external organizations to foster extremism and terrorism. -

New Sops for Wedding Halls, Restaurants

Soon From LAHORE & KARACHI A sister publication of CENTRELINE & DNA News Agency www.islamabadpost.com.pk ISLAMABAD EDITION IslamabadTuesday, October 06, 2020 Pakistan’s First AndP Only DiplomaticO Daily STPrice Rs. 20 Aziz Boolani: A UAE interested in EU envoy lauds symbol of positivity Pak development master Ayub’s and optimism projects: Envoy teaching services Briefs New SOPs for Army, people eliminated wedding halls, terrorism ISLAMABAD: Chairman restaurants CPEC Au- thority Asim Saleem Baj- SOPs related to marriage halls would wa Monday be issued on Wednesday, number of called on Chief Minis- citizens and working hours would be ter Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Mahmood Khan in Pesha- fixed in marriage halls war and discussed progress of projects under China Pa- kistan Economic Corridor nihal miRaj 165 restaurants, (CPEC) in the province. During the meeting, they ISLAMABAD: The government has de- 9 halls sealed also discussed future projects cided to issue new SOPs related to wed - ding halls and restaurants in the wake of KARACHI: Local administration of Karachi that would be presented in has sealed nine wedding halls and 165 res- the upcoming meeting of Coronavirus. Talking to media, Federal Minister Asad Umar said that in the first taurants for violating Coronavirus SOPs in Pak-China Joint Coordination Karachi. According to the details, cases of Committee (JCC) of CPEC phase, SOPs related to marriage halls would be issued on Wednesday, number coronavirus have been increasing in Kara- for approval for inclusion in chi in the last few days, after which smart ISLAMABAD: Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Zafar Mahmood Abbasi the mega project. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

Shareholders Without CNIC.PDF

Gharibwal Cement Limited DETAIL OF WITHOUT CNIC SHAREHOLDERS S.No. Folio Name Address Current Net Dividend shareholding (Net of Zakat and Balance tax) 1 1 HAJI AMIR UMAR C/O.HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR COTTON MERCHANT,3RD FLOOR COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG, MCLEOD ROAD, P.O.BOX.NO.4124 586 KARACHI 578 2 3 MR.MAHBOOB AHMAD MOTI MANSION, MCLEOD ROAD, LAHORE. 11 11 3 11 MRS.FAUZIA MUGHIS 25-TIPU SULTAN ROAD MULTAN CANTT 1,287 1,271 4 19 MALIK MOHAMMAD TARIQ C/O.MALIK KHUDA BUX SECRETARY AGRICULTURE (WEST PAKISTAN), LAHORE. 110 108 5 20 MR. NABI AHMED CHAUDHRI, C/O, MODERN MOTORS LTD, VOLKSWAGEN HOUSE, P.O.BOX NO.8505, BEAUMONT ROAD, KARACHI.4. 2,193 2,166 6 24 BEGUM INAYAT NASIR AHMED 134 C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 67 66 7 26 MRS. AMTUR RAUF AHMED, 14/11 STREET 20, KHAYABAN-E-TAUHEED, PHASE V,DEFENCE, KARACHI. 474 468 8 27 MRS.AMTUL QAYYUM AHMED 134-C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 26 25 9 31 MR.ANEES AHMED C/O.DR.GHULAM RASUL CHEEMA BHAWANA BAZAR, FAISALABAD 649 642 10 36 MST.RAFIA KHANUM C/O.MIAN MAQSOOD A.SHEIKH M/S.MAQBOOL CO.LTD ILAMA IQBAL ROAD, LAHORE. 1,789 1,767 11 37 MST.ABIDA BEGUM C/O HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR 3RD FLOOR. COTTON EXCHANGE BUILDING, 1.1.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD, KARACHI. 2,572 2,540 12 39 MST.SAKINA BEGUM F-105 BLOCK-F ALLAMA RASHID TURABI ROAD NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2,657 2,625 13 42 MST.RAZIA BEGUM C/O M/S SADIQ SIDDIQUE CO., 32-COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG., I.I.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI.