Quakers on the Spectrum of Nonviolence: in Conversation with K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

H-Peace Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement' Review published on Monday, March 1, 2004 Thomas F. Curran. Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003. xv + 228 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8232-2210-0. Reviewed by Peter Brock (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- Peace (March, 2004) Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Thomas Curran's monograph originated in a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Notre Dame but it has been much revised since. The book's clearly written and well-constructed narrative revolves around the person of an obscure package woolen commission merchant from Philadelphia named Alfred Henry Love (1830-1913), a radical pacifist activist who was also a Quaker in all but formal membership. Love is the key figure in the book, binding Curran's chapters together into a cohesive whole. And Love's papers, and particularly his unpublished "Journal," which are located at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, form the author's most important primary source: in fact, he uses no other manuscript collections, although, as the endnotes and bibliography show, he is well read in the published primary and secondary materials, including work on the general background of both the Civil War era and nineteenth-century pacifism. Curran has indeed rescued Love himself from near oblivion; there is little else on him apart from an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Robert W. Doherty (University of Pennsylvania, 1962). -

Tolstoy and the Christian Lawyer

Catholic University Law Review Volume 52 Issue 2 Winter 2003 Article 5 2003 Tolstoy and the Christian Lawyer Raymond B. Marcin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Raymond B. Marcin, Tolstoy and the Christian Lawyer, 52 Cath. U. L. Rev. 327 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOLSTOY AND THE CHRISTIAN LAWYER Raymond B. Marcin' It may be that there is no literate person alive in the Western world who has not heard of Count Lyof Nikolaevich Tolsto' (Tolstoy), author of what some have called the quintessential novel among all recorded literature: War and Peace. It may also be that most literate persons are aware that Tolstoy was a moralist of some renown-of great renown in his day-whose pacifist thought presaged and influenced Mohandas K. Gandhi, the great and saintly Mahatma of India. One doubts, however, whether many are aware that Tolstoy penned what is perhaps the most devastating attack in all religious literature on the thesis that a Christian can be a lawyer and remain a true Christian. I. THE PROBLEM We often espouse great ideals in the context of law and lawyering, but whenever we turn our attention to the world of contemporary reality, we are forced to admit that there is something wrong with law and lawyering. -

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

CHURCH, MARJORIE ROSS, Ph.D. Teaching Peace: an Exploration of Identity Development of Peace Educators

CHURCH, MARJORIE ROSS, Ph.D. Teaching Peace: An Exploration of Identity Development of Peace Educators. (2015) Directed by Dr. H. Svi Shapiro. 198 pp. The purpose of this research was to explore the identity of those who can be called “Peace Educators,” and to contextualize the concept of that identity within the field of Peace Education by presenting an historical background of the field and by exploring various models of Peace Education programming. Five professionals whose work encompasses the theories and practices associated with Peace Education were interviewed for this study. Their stories were examined in light of the various convergences and intersections regarding a conceptual framework that included religion and spirituality, sociology, cultural studies, feminism, critical pedagogy, global concerns, economic concerns, environmentalism, and a central concern for social justice. The research indicated that although there are various areas of similarity between the participants as well as others whose work has been seminal in creating the field of Peace Education, there is not an essential set of characteristics or behaviors that can be deemed uniquely associated with an identity called “Peace Educator.” In fact, the research indicates that it is the practice of Peace Education itself that determines such an identity, and it remains fluid and multifaceted despite its clear connections with the various concerns that were examined. TEACHING PEACE: AN EXPLORATION OF IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT OF PEACE EDUCATORS by Marjorie Ross Church A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2015 Approved by Committee Chair © 2015 Marjorie Ross Church To all of my family, friends, extended family, and colleagues—thank you for your support and your encouragement along the way. -

Northwest Friend, July 1963

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Northwest Friend (Quakers) 7-1963 Northwest Friend, July 1963 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Northwest Friend, July 1963" (1963). Northwest Friend. 228. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend/228 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JULY ORTUIUCCT 1 9 6 3 "Quaker Journal of the Pacific Northwest" Vol. XLIII No. 5 OREGON TING of FRIENDS CHURCH in session at Newberg, Oregon AUGUST 13-18, 1963 I.Yearly Meetlllg Speaker Make Arrangements -Editorial SUPERINTENDENT'S For Yearly Meeting Now! CORNER Yearly Meeting time is almost here. Re ports and messages are being prepared. The Entertainment Committee of Newberg Quar terly Meeting is making plans for your com Let Nothing Move You By Dean Gregory fort and convenience and want you to feel wel come. Your cooperation in making arrange EARLY MEETING, 1963. Will it be the m e n t s f o r y o u r s t a y i n N e w b e r g w i l l h e l p i n this. Please note the following items: INDING up one of the most marvelous explanations of the resurrection greatest yet or will we take it as just ever given, the apostle Paul swings his attention momentarily to those another page in our year's calendar? • Necessary charges are listed with the y w of us who are not exactly candidates for heaven yet and says, "And so The program sounds interesting as 1 hear Yearly Meeting program. -

The Quaker Peace Testimony and Masculinity

The early Quaker peace testimony and masculinity in England, 1660-1720 Shortly after his Restoration in 1660, Charles II received ‘A Declaration from the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers’ announcing their principles of seeking peace and the denial of ‘[a]ll bloody principles and practices’, as well as ‘outward wars and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretense whatsoever’.1 The early Quaker peace testimony, represented by the 1660 ‘Declaration’, was closely related to refashioned Quaker masculinity after the Restoration. As Fox wrote in the ‘Declaration’, contrasting the dishonourable, unmanly nature of worldly men with the manly bravery of Quakers, ‘It is not an honour, to manhood or nobility, to run upon harmless people, who lift not up a hand against them, with arms and weapons.’2 Such bold assertions were commented upon almost immediately; as the prophet and visionary defender of the Church of England Arise Evans responded, ‘The Quakers give out forsooth, that they will not rebel nor fight, when indeed the last year, and all along the War, the Army was full of them.’3 Although this was not entirely the case, the public declaration of Friends’ rejection of war was a cornerstone of refashioned Quaker masculinity from the Restoration. Karen Harvey and Alexandra Shepard assert that most research into the history of masculinity has concentrated on dominant groups of men, whilst more work is needed on the range of different codes available to others, and as Shepard goes on to suggest, -

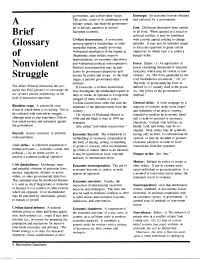

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

The Cult of Liberation: the Berkeley Free Church and the Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 Volume 1

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship 1977 The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1 Harlan Stelmach Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Stelmach, Harlan, "The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1" (1977). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 52. https://scholar.dominican.edu/all-faculty/52 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977 HARLAN DOUGLAS ANTHONY STELMACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED : TlIE CULT OF LIIiER.'i.TION THE SEPKELEY FREE CHURCH and THE RADICAL CHURCH MOVEMENT 1967-1972 A dissertiatlon by Harlan Douglas Anthony _S_tein)ach presented to Tae Faculty of the Graduate Theological Union in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Berkeley, California May 15, 1977 Committee Signatures: Co-Coordjnator ^ y^oV^K- t\M^ Co-Coordinator f 'il -7^ ^- With special thanks to all those who have been part of the process which helped to shape me and this dissertation: MADELYN Joy Aiiy Anne Megan Linda P. ***** Tony Fred G. John M. Edie Bill Jon Joe H. Nancy Gordon Suzanne J. Bob D. Marilena Hugh Sergio Bob C. -

Peace in Print

Peace in print Originally written on the Operating System CP/M 2.2 and the Word Processing Program Word Star 2.2 Converted into and continued in Word Perfect 5.1 and 7.0. Converted into html 2001. Dk=5: 01.6157. 01.6323. 01.63551. 15.7. 32.3. 35.51 Copyright 1991-2001 © Holger Terp. This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. All rights are reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1956, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, chemical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Holger Terp. Strandbyparken 4. 1 tv. 2650 Hvidovre. Denmark. 009 45 (3) 1 78 40 28. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the late Hans-Henrik Pusch of Copenhagen whose kind generosity inspired and made this work much more complete than it otherwise would have been; Librarian Betty Nielsen, Librarian Katherine Laundry at Canadian Institute for International Peace and Security - Ottawa. The staffs at The Royal Library - Copenhagen, Odense University Library, The Labor Movement Library and Archive - Denmark - Copenhagen, The Labor Movement Archive and Library - Norway - Oslo, The Library of the Nobel Institute - Oslo, The International Institute of Social History - Amsterdam (who keep the files of WRI), International Archives of the Women's Movement - Amsterdam, McCabe Library - Swartmore (where the Swartmore College Peace Collection is located), The Periodical Center - Copenhagen, The Library at Guldbergsgade - Copenhagen, The Royal School of Librarianship at Copenhagen. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abhidharma, 143 atonement theory/soteriology (how Jesus’ Abraham, 13, 85 death saved humanity), 54 Abu Talib, 10 Augustine, 57–8, 69, 81 Acts of the Apostles, 47 aum (om) shanti (silence, tranquility of Afghanistan, 21, 35, 219 mind, listening to inner voice, etc.), 180 ‘afw (forgiveness), 41 Ayoub, Mahmoud M., 11, 18–19 ahimsa (nonviolence), 180–2 Aztecs, 110 Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, 17 Alvarado, Pedro, 59 ba (hegemony), 126 American Indian veterans of the US war Babylonian Talmud, 83–4, 89, 93–4 against Vietnam, 212 baoli (violence), 123 American Israel Public Affairs Committee, 100 Bar Kosiba, Simon, 93, 105 American Jewish Committee, 101 Beatitudes, 51, 69 Anabaptists, 61 Bell, Daniel, 124 Analects, 112–14, 124 Bhagavad Gita (Gita), 14, 178, 181–2, 203 Anandavan, 190–91 bhakti (personal devotion), 180 anthropocentrism, 215–17 Bhave, Vinoba, 174, 194 Anti-Defamation League, 99 Bible, 2, 14–15, 84, 87, 90–1, 143, 149, 188, anti-semitism, 63 194, 217 Arab nationalism, 45 Bodhisattva, 143, 147–50, 153 Arab Spring, 21 Bonney, Richard, 15, 23 Arab-Israeli Wars, 96–7 Brahman (ultimate reality), 4, 154, 179, 198 Ariaratne, A. T., 158, 174 Brahmins, 173, 179, 184 Arjuna, 179, 181–3, 200 Buber, Martin, 89 Art of Living Foundation, 191 Buddha, 78, 80, 135–6, 143, 145, 147–8, Ashrams: communities practicing yoga 154–5, 157, 173–4, 185, 188, and serviceCOPYRIGHTED to others, 190 Buddhism MATERIAL forms: Asita, 135 Theravada, 142–4, 148, 152, 156 Athavale, Pandurang Shastri, 194 Mahayana, 76, 142, 136, 143–4, 147–8, atman (soul), 179, 198, 203–4 150, 152, 157, 160–3, 168 Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions, First Edition. -

Meeting in Exile

Meeting In Exile Gerald W. Schlabach Gerald W. Schlabach is associate professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, and director of the university's Justice and Peace Studies Program. He is lead author and editor of Just Policing, Not War: An Alternative Response to World Violence (Liturgical Press, 2007) and co-editor of At Peace and Unafraid: Public Order, Security and the Wisdom of the Cross (Herald Press, 2007). From 2001 through 2007 he was executive director of Bridgefolk, a movement for grassroots dialogue and unity between Mennonites and Roman Catholics. For the three “historic peace church” colleges of Indiana to join together in the Plowshares Peace Studies Collaborative and its new Journal of Religion, Conflict, and Peace is altogether welcome and obviously fitting. The term “historic peace church” that links the Mennonite Church, the Religious Society of Friends, and the Church of the Brethren is, however, somewhat less obvious. Or rather, it has come to seem obvious mainly by historical accident, and then by force of habit. If the term had emerged in a context other than the United States in the years leading up to World War II, after all, other historic Christian communities might have been included, so, too, if the term ever undergoes revision in the twenty-first century. Just what constitutes a “peace church” in the first place? The question is deceptively simple. So let me begin by complicating it! A brief story may illuminate the complexity. In 1998 the first formal international ecumenical dialogue began between Mennonites and Roman Catholics.