An Assessment of Seabee Compensation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Changes to Recruit Training by Dayton Ward

The U.S. Army is updating its basic training curriculum with an eye toward instilling improved discipline, better physical fitness, and an enhanced appreciation for Army values and the ethics of the professional Soldier. (Graphic by NCO Journal) Back to Basics Big Changes to Recruit Training By Dayton Ward asic Combat Training or the "Ten-Week Journey ia, the Army takes an assessment of its basic training from Civilian to Soldier"1 is the foundation upon curriculum every three years per U.S. Army Training and which the Army builds professional, principled Doctrine Command policies. Bwarriors. More than 100,000 men and women undertake "With these normal assessments and discussions this training each year.2 with key leaders, we are getting after the 'Soldierization' As our nation faces evolving and more complex process," Mitchell said.3 challenges, it is vital to turn a critical eye toward the pro- Beginning in 2015, the Army surveyed more than cesses affecting this most fundamental aspect of military 27,000 Soldiers across the officer and noncommissioned training. Recognizing this need, the Army is in the midst officer ranks, asking them to identify the most common of evaluating and improving how it creates Soldiers and deficiencies in recent BCT and Advanced Individual ensuring recruits who graduate basic training are ready Training graduates. Topping the list was a lack of disci- to tackle the responsibilities the Army will soon place pline among new Soldiers, such as arriving late for duty upon them. assignments or failing to wear uniforms correctly. Also highlighted was a failure to show respect to senior-rank- Assessing the Situation ing Soldiers and failure to follow orders.4 According to Command Sgt. -

Audit of the Impact of Coronavirus Disease–2019 on Basic Training

Report No. DODIG-2021-069 CUI U.S. Department of Defense InspectorMARCH 31, 2021 General Audit of the Impact of Coronavirus Disease–2019 on Basic Training Controlled by: DoD OIG Controlled by: Readiness and Global Operations CUI Category: Operational Security Information Distribution/Dissemination Control: FED ONLY POC: INTEGRITY INDEPENDENCE EXCELLENCE CUI CUI CUI WORKING DRAFT CUI Audit of the Impact of Coronavirus Disease–2019 Resultson Basic Training in Brief March 31, 2021 Background (cont’d) Objective training center and all of the basic training centers for the Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force. The six basic training The objective of this audit was to determine centers selected for review were: whether the DoD established and the Military • U.S. Army Training Center and Fort Jackson, Services implemented procedures to prevent South Carolina; and reduce the spread of coronavirus disease–2019 (COVID-19) at their basic • Marine Corps Recruit Depots, Parris Island, Backgroundtraining centers. South Carolina, and San Diego, California; • Navy Recruit Training Command, Great Lakes, Illinois; and COVID-19 is an infectious disease that • Air Force Basic Training Center Joint Base can cause a wide spectrum of symptoms. San Antonio–Lackland, Texas and Keesler On March 11, 2020, the World Health Air Force Base, Mississippi. Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak Finding a pandemic, and on March 13, 2020, the President declared the COVID-19 pandemic a Despite the challenges with the global pandemic, the DoD national emergency. COVID-19 can transmit and Military Services established procedures to prevent and from person to person within 6 feet when reduce the spread of COVID-19. -

United States Naval Sea Cadet Corps Recruit Training Command New England

UNITED STATES NAVAL SEA CADET CORPS R ECRUIT TRAINING COMMAND NEW ENGLAND 01 July 2019 – 13 July 2019 · Fort Devens, Massachusetts www.newenglandseacadets.org/training/rtc LCDR Christopher Donahue, NSCC · Commanding Officer of the Training Contingent PARENT INFORMATION GUIDE VERSION 1.0 (UPDATED 10MAR19) This guide contains essential information about getting your cadet signed up and prepared for training – please read the whole guide. You and your cadet will have a much better training experience if you both know what to expect!! Sec. Topic Page §1. When is Recruit Training? ............................................................................................ 2 §2. Where is Recruit Training? How do I get on the base? ............................................... 2 §3. What are the qualifications for Recruit Training? ........................................................ 2 §4. What do I have to do to get my Recruit a billet at Recruit Training? .......................... 3 §5. What happens on Check-In Day? ................................................................................. 3 §6. Check-In: Physical Fitness Test ................................................................................... 4 §7. Why is the PFT part of Check-In? ................................................................................ 4 §8. What if my Recruit gets injured before Recruit Training starts? .................................. 4 §9. What if my Recruit has a disability? ............................................................................ -

An Analysis of Marine Corps Female Recruit Training Attrition

An Analysis of Marine Corps Female Recruit Training Attrition (b) (6) December 2014 (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (b) (6) (6) Distribution limited to sponsor only. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution Distribution limited to sponsor only. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Photography Credit: Recruits from (b) (6) negotiate the “Run-Jump-Swing” on the Marine Corps Confidence Course. Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, SC, Oct. 3, 2012. (U. S. Marine Corps photo by L(b) (6) Released) Approved by: December 2014 (b) (6) Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division Copyright © 2014 CNA Abstract Over the past several years, the Department of Defense has asked the services to pursue expanded opportunities for women in the military. To support this effort, the Marine Corps started a deliberate and measured effort to examine the possible integration of women into ground combat units and military occupational specialties (MOSs) with the development of the Marine Corps Force Integration Plan (MCFIP). In turn, the Marine Corps asked CNA to examine female recruit training attrition. We examined the relationship between female recruit training attrition and four general groups of factors: (1) recruit characteristics, (2) recruiter and recruiter/recruit interaction characteristics, (3) recruiting substation leadership and management metrics, and (4) shipping timing factors. Although recruit characteristics and shipping timing factors continue to be the best predictors of female recruit training success, we found some interesting relationships between attrition and (1) recruiter and recruiter/recruit interaction characteristics and (2) recruiting substation leadership/management metrics. -

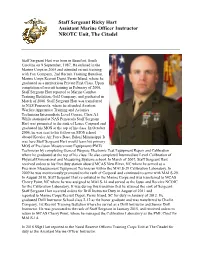

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, the Citadel

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, The Citadel Staff Sergeant Hart was born in Beaufort, South Carolina on 9 September, 1987. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2005 and attended recruit training with Fox Company, 2nd Recruit Training Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, where he graduated as a meritorious Private First Class. Upon completion of recruit training in February of 2006, Staff Sergeant Hart reported to Marine Combat Training Battalion, Golf Company, and graduated in March of 2006. Staff Sergeant Hart was transferred to NAS Pensacola, where he attended Aviation Warfare Apprentice Training and Avionics Technician Intermediate Level Course, Class A1. While stationed at NAS Pensacola Staff Sergeant Hart was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal and graduated his MOS at the top of his class. In October 2006, he was sent to his follow on MOS school aboard Keesler Air Force Base, Biloxi Mississippi. It was here Staff Sergeant Hart would learn his primary MOS of Precision Measurement Equipment (PME) Technician by completing General Purpose Electronic Test Equipment Repair and Calibration where he graduated at the top of his class. He also completed Intermediate Level Calibration of Physical/Dimensional and Measuring Systems school. In March of 2007, Staff Sergeant Hart received orders to his first duty station aboard MCAS New River, NC where he served as a Precision Measurement Equipment Technician within the MALS-29 Calibration Laboratory. In 2009 he was meritoriously promoted to the rank of Corporal and continued to serve with MALS-29. In August 2010, Staff Sergeant Hart re-enlisted in the Marine Corps and was transferred to MCAS Cherry Point, NC where he was assigned to MALS-14 and served as the Issue and Receive NCOIC for the Calibration Laboratory. -

Training Officers Manual

TRAINING OFFICERS MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 TRAINING Page 1-1 General Page 1-1 Purpose Page 1-1 Mission Page 1-1 Objectives Page 1-1 Categories of Young Marines Training Page 1-1 National Training Programs Page 1-1 Adventures Page 1-1 Challenges Page 1-1 Encampments Page 1-2 Schools Page 1-2 Special Programs Page 1-2 Application Process Page 1-2 Unit Training Page 1-2 Unit Training Meetings Page 1-2 Monthly Training Schedule Page 1-2 Planning Process Page 1-3 Recruit Training Page 1-3 Physical Training Page 1-5 Ages 8 Page 1-5 Ages 9-11 Page 1-5 Ages 12-18 Page 1-5 Trips and Outings Page 1-6 General Training Safety Page 1-6 CHAPTER 2 PROMOTION REQUIREMENTS Page 2-1 Purpose Page 2-1 Restrictive and Non-restrictive Promotions Page 2-1 Mandatory Requirements Page 2-1 Oral Promotion Board Page 2-1 Physical Fitness Page 2-2 Recommendations for Promotions Page 2-2 Meritorious Promotions Page 2-3 Grandfather Clause Page 2-3 Table of Promotions Page 2-4 Leadership School Requirements Page 2-6 Advanced Young Marine Initiatives Page 2-6 National Promotion Exams Page 2-6 CHAPTER 3 YOUNG MARINE RECRUIT TRAINING SOP Page 3-1 Situation Page 3-1 Mission Page 3-1 Execution Page 3-1 National Executive Director’s Training Philosophy Page 3-1 National Executive Director’s Intent Page 3-1 Concept of Operations Page 3-1 Tasks Page 3-2 Coordinating Instructions Page 3-2 Training Execution Page 3-3 Training Day Page 3-3 Basic Daily Routine Page 3-3 Sleep Page 3-3 Young Marine Recruit Rights Page 3-3 Administration and Logistics Page 3-4 Personnel Qualifications -

Neptune's Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy

Neptune’s Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy A Coast Guard LCVP landing craft crew prepares to take soldiers to Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944 Photo 26-G-2349. U.S. Coast Guard Photo, Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command By Michael Kern Program Assistant, National History Day 1 “The point was that we on the scene knew for sure that we could substitute machines for lives and that if we could plague and smother the enemy with an unbearable weight of machinery in the months to follow, hundreds of thousands of our young men whose expectancy of survival would otherwise have been small could someday walk again through their own front doors.” - Ernie Pyle, Brave Men 2 What is National History Day? National History Day is a non-profit organization which promotes history education for secondary and elementary education students. The program has grown into a national program since its humble beginnings in Cleveland, Ohio in 1974. Today over half a million students participate in National History Day each year, encouraged by thousands of dedicated teachers. Students select a historical topic related to a theme chosen each year. They conduct primary and secondary research on their chosen topic through libraries, archives, museums, historic sites, and interviews. Students analyze and interpret their sources before presenting their work in original papers, exhibits, documentaries, websites, or performances. Students enter their projects in contests held each spring at the local, state, and national level where they are evaluated by professional historians and educators. The program culminates in the Kenneth E. Behring National Contest, held on the campus of the University of Maryland at College Park each June. -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

MAGAZINE of the U.S. NAVY I Staff Sgt

MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY I Staff Sgt. Laroy Streets, of Glen Burnie, Md., coaches AT3 Josh Roberts, of Austin, Texas, at the Puuloa Marine Corps pistol range, Hawaii. Photo by PH2 Kerry E. Baker, Fleet Imaging Command Pacific, NAS Barbers Point., Hawaii. Contents Magazine of the U.S. NavySeptember 1995, Number 941 :4 27 0 0 0 Best of the best fly toLearning 0 : Meet the Navy's Sailors of the Year Afterfive weeks of exercise, NAS 0 for 1995. Pensacola,Ha., turns out aircrewmen : 0 who are ready to fly. 0 0 0 0 31 0 0 The great rescue USS Kearsarge(LHD 3) Sailorsand Challenge Athena 0 0 embarkedMarines bring Air Force Hightech on the highseas brings 0 today's Sailors a little closer to home. Capt.Scott OGrady home. 0 0 PAGE 4 0 0 34 0 : 14 0 It'snot remote any more 0 0 PCU Gonzalez (DDG66) 0 ArleighBurke-class destroyer DigitalSatellite System TV is closer 0 named for Vietnam War Medal of thanyou think. Get the lowdown and : Honorwinner. see if it's coming to your living room. 0 0 0 36 0 16 0 0 : Growing Navy leaders home Welcome 0 FamilyService Centers now have 0 The Naval Sea Cadet Corps is more WelcomeAboard Videos available than just something to do after : 0 throughtheir Relocation Assistance school. PAGE 6 0 program. 0 0 : 18 0 0 0 38 Getting out alive 0 Starbase AtlantisStarbase 0 : Watersurvival training teaches The Fleet Training Center, Atlantic, 0 pilots, flight officers and aircrew Norfolk, provides a forum for students membershow to survive. -

Tobacco Use and the United States Military: a Longstanding Problem

Tobacco Control 1998;7:219–221 219 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.7.3.219 on 1 September 1998. Downloaded from Tobacco use and the United States military: a longstanding problem Ties between the United States military and the tobacco negative relationships between smoking and various meas- industry trace back to the early parts of the 20th century. ures of “performance readiness”. Smokers exercise less During the second world war, for example, cigarette adver- and perform more poorly on physical fitness tests,15–17 and tisements praising service members were widespread on they are less successful in combat training.18 19 Smokers popular radio programmes and in periodicals.1 Some ads also have higher rates of various types of illnesses and even featured cigarette-using doctors vouching for the absenteeism from the job.20 21 The eVects of regular great taste and mildness of particular brands. Cigarettes tobacco use clearly are incompatible with maintaining the were also included as part of the K-rations and C-rations physical abilities necessary to perform at peak levels in the provided to soldiers and sailors during the second world very physically demanding jobs that are commonplace in war, and these cigarettes frequently became more valuable the military. for trading or selling than the food items in the rations. Data presented by Haddock et al 22 in this issue of During times of war and peace, many young people Tobacco Control provide further evidence that smoking is (predominantly men, as they have traditionally comprised still a matter for concern even among air force personnel, the bulk of military personnel) started smoking after they who have lower smoking rates than all of the other services. -

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of An

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with JOE DREES Leading Petty Officer, Navy, Operation Iraqi Freedom 2016 OH 2065 OH 2065 Drees, Joe (b. 1956) Oral History Interview, 2016 Approximate length: 2 hours 21 minutes Contact WVM Research Center for access to original recording. Abstract: In this oral history interview, Joe Drees, a resident of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, talks about his career in the Navy and the Navy Reserves from 1980 until 2006, includ ing a deployment to Iraq in 2006 as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Drees discusses his early life growing up near Sheboygan, Wisconsin and his education at a Catholic school. He talks about training in the Merchant Navy before leaving after two years due to an injury that occurred while onboard a ship. He then worked various jobs before joining the Navy in 1980 where he specialized in nuclear power, undertaking his classroom training at the Orlando Naval Training Center in Florida. From there, Drees did further training on a prototype reactor near Ballston Spa, New York before being stationed onboard USS Enterprise, USS Nimitz, and USS Carl Vinson. Drees talks at length about day-to-day life onboard ship and the practical aspects of his job. He describes shore duty at Bremerton, Washington and San Diego, California. After 14 years' service, he left the Navy in 1995 and moved back to Wisconsin with his wife. Drees was employed by Kohler Company and continues to work there today. In 1997, he joined the Navy Reserves and describes the work and training as a Seabee, a member of the Naval Construction Forces. -

An Island Worth Defending the Midway Atoll

An Island Worth Defending The Midway Atoll Presented by Steve Spiller Redlands Fortnightly Meeting #1748 May 10, 2007 An Island Worth Defending The Midway Atoll Introduction Families of World War II uniformed men and women, as a rule, had little understanding of their loved one’s experiences. Renewal of lives interrupted prevailed following the war. Memories emerged gradually as veterans reconnected to those with whom they fought side by side, as time lengthened and lost letters were found. Today, these memories provide an essential element to our appreciation of “The Greatest Generation.” One young Marine inspired me to research the Battle of Midway and the history preceding the events of June 4, 1942. For eighteen months, the tiny atoll west of Pearl Harbor was my father’s home. The island littered with guano that welcomed wealthy transpacific air passengers would defend itself in the battle that historians say rivals Trafalgar, Saratoga, and the Greek battle of Salamis. Marion Timothy Spiller stepped onto the extinct volcano in September 1941. The abandoned cauldron encircled by coral “with the most beautiful dawns and sunsets in the world” was his home through February 1943.1 The son of a Methodist minister, Marion’s enlistment in October 1939 provided the opportunity to leave the Midwest for the welcoming warmth of San Diego. Midway Description Twelve hundred and sixty nautical miles north-west of Pearl Harbor sits Midway Island, or more correctly, the Midway Atoll. Three fragments of land, surrounded by a reef five miles in diameter, are all that remain above the water’s surface of the age-old volcano.