Clarifications Required by the Book Being Religious Interreligiously: Asian Perspectives on Interfaith Dialogue by Reverend Peter C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

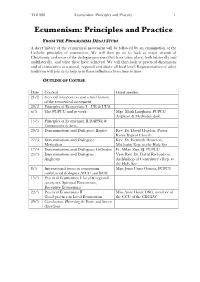

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 1994 The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Thomas P. “The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory,” Mid-Stream 33 (1994): 275-288. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas P. Rausch The Promise of the ew Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch, S. J., is Professor of Theological Studies and Rector of the Jesuit Community at Loyola Marym01.1nt University, Los Angeles, California, and chair of the department. A specialist in the areas of ecclesiology, ecumenism, and the theology of the priesthood, he is the author of five books and numerous articles. he new Roman Catholic Ecumenical Directory (ED), officially titled the Directory for the Application ofPrinciples and Norms on Ecumenism, was released on June 8, 1993 by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. 1 In announcing it, Pope John Paul II said that its preparation was motivated by "the desire to hasten the journey towards unity, an indispensable condition for a truly re newed evangelization. "2 The pope's linking of Christian unity with a renewal of the Church's work of evangelization is important, for the very witness of the Church as a community of humankind reconciled in Christ is weakened by the obvious lack of unity among Christians. -

Pdf (Accessed January 21, 2011)

Notes Introduction 1. Moon, a Presbyterian from North Korea, founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity in Korea on May 1, 1954. 2. Benedict XVI, post- synodal apostolic exhortation Saramen- tum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), http://www.vatican.va/holy _father/benedict_xvi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi _exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis_en.html (accessed January 26, 2011). 3. Patrician Friesen, Rose Hudson, and Elsie McGrath were subjects of a formal decree of excommunication by Archbishop Burke, now a Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signa- tura (the Roman Catholic Church’s Supreme Court). Burke left St. Louis nearly immediately following his actions. See St. Louis Review, “Declaration of Excommunication of Patricia Friesen, Rose Hud- son, and Elsie McGrath,” March 12, 2008, http://stlouisreview .com/article/2008-03-12/declaration-0 (accessed February 8, 2011). Part I 1. S. L. Hansen, “Vatican Affirms Excommunication of Call to Action Members in Lincoln,” Catholic News Service (December 8, 2006), http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0606995.htm (accessed November 2, 2010). 2. Weakland had previously served in Rome as fifth Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation (1967– 1977) and is now retired. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2009). 3. Facts are from Bruskewitz’s curriculum vitae at http://www .dioceseoflincoln.org/Archives/about_curriculum-vitae.aspx (accessed February 10, 2011). 138 Notes to pages 4– 6 4. The office is now called Vicar General. 5. His principal consecrator was the late Daniel E. Sheehan, then Arch- bishop of Omaha; his co- consecrators were the late Leo J. -

The 'Enemy Within' the Post-Vatican II Roman Catholic Church

Page 1 of 8 Original Research The ‘enemy within’ the post-Vatican II Roman Catholic Church Author: The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) is regarded as one of the most significant processes Graham A. Duncan1 in the ecumenical church history of the 20th century. At that time, a younger generation of Roman Catholic theologians began to make their mark in the church and within the ecumenical Affiliation: 1Department of Church theological scene. Their work provided an ecumenical bridge between the Reforming and the History and Church Polity, Roman Catholic ecclesiastical traditions, notwithstanding the subsequent negative response University of Pretoria, of the Roman church hierarchy. Despite important advances, recent pontificates significantly South Africa altered the theological landscape and undermined much of the enthusiasm and commitment Correspondence to: to unity. Roman Catholic theological dissent provided common ground for theological Graham Duncan reflection. Those regarded as the ‘enemy within’ have become respected colleagues in the search for truth in global ecclesiastical perspective. This article will use the distinction between Email: the history and the narratives of Vatican II. [email protected] Postal address: Faculty of Theology, Introduction University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa The second Vatican Council (1962–1965) was a theological watershed for the Roman Catholic Church. Despite valiant attempts by the Curial administration to maintain rigid continuity with Dates: the past, a new generation of theologians emerged which represented the aggiornamento that Received: 06 Jan. 2013 Accepted: 30 Mar. 2013 Pope John XXIII so earnestly desired. This group was at the forefront of providing grounds for a Published: 31 May 2013 rapprochement with Reforming theology. -

Vassula Ryden Press Release

Vassula Ryden Press Release http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/CDFRYDN2.HTM NOTIFICATION ON VASSULA RYDEN (Dec 1996) Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (This clarification of its original Notification on Vassula Ryden was released to the Press in December 1996) I. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has received various questions about the value and authority of its Notification of 6 October 1995, published in L'Osservatore Romano on Monday/Tuesday, 23/24 October 1995, p. 2 (L'Osservatore Romano English edition, 25 October 1995, p. 12), regarding the writings and messages of Mrs. Vassula Ryden attributed to alleged revelations and disseminated in Catholic circles throughout the world. In this regard, the Congregation wishes to state: 1) The Notification addressed to the Pastors and faithful of the Catholic Church retains all its force. It was approved by the competent authorities and will be published in Acta Apostolicae Sedis, the official organ of the Holy See, with the signatures of the Prefect and the Secretary of the Congregation. [*] 2) Regarding the reports circulated by some news media concerning a restrictive interpretation of this Notification, given by His Eminence the Cardinal Prefect in a private conversation with a group of people to whom he granted an audience in Guadalajara, Mexico, on 10 May 1996, the same Cardinal Prefect wishes to state: a) as he said, the faithful are not to regard the messages of Vassula Ryden as divine revelations, but only as her personal meditations; b) these meditations, as the Notification explained, include, along with positive aspects, elements that are negative in the light of Catholic doctrine; c) therefore, Pastors and the faithful are asked to exercise serious spiritual discernment in this matter and to preserve the purity of the faith, morals and spiritual life, not by relying on alleged revelations but by following the revealed Word of God and the directives of the Church's Magisterium. -

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sources .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Worship Services .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Norms of Reciprocity and Collaboration .................................................................................................................... 5 Sharing in Non‐Sacramental Liturgical Worship ...................................................................................................... 6 Ecumenical Services ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Interfaith Services .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Sharing in God’s Word in Sacred Scripture ................................................................................................................ 7 Sacramental Celebrations ............................................................................................................................................. -

The Holy See

The Holy See CALENDAR 2013 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL MAY JUNE JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER MARCH 2013 HABEMUS PAPAM 13 Wednesday Photo Gallery 14 Thursday Basilica of Saint Mary Major Prayer of Pope Francis to the Salus Populi Photo Gallery Romani Video Photo Gallery Holy Mass with the Cardinal electors Sistine Chapel, at 17:00 Homily of the Holy Father [Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish] Video 15 Friday Photo Gallery Clementine Hall, at 11:00 Audience with the Cardinals Address of the Holy Father [English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish] 16 Saturday Video Paul VI Audience Hall, at 11:00 Address of the Holy Father Audience to the media representatives [English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish] 2 Video 17 - 5th Sunday of Lent Photo Gallery Parish of St. Anna in the Vatican, at 10:00 Photo Gallery 2 Holy Mass Homily of the Holy Father [English, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish] Video Saint Peter's Square, at 12:00 Words of the Holy Father Angelus [Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish] 18 Monday Domus Sanctae Marthae, at 12:50 Meeting with the President of the Republic of Argentina Notification Booklet for the Celebration 19 Tuesday Video Solemnity of St. Joseph, Spouse of the Photo Gallery Blessed Virgin Mary Photo Gallery 2 Saint Peter's Square, at 9:30 PAPAL MASS Imposition of the Pallium Imposition of the Pallium, bestowal of the [English, Italian] Fisherman's Ring and Holy Mass for the Bestowal of the Fisherman's -

The Holy See

The Holy See LATEST EVENTS ARCHIVE 2013 Wednesday, 6 August 2014 Paul VI Hall, at 10:30 General Audience Sunday, 3 August 2014 Video Saint Peter's Square, at 12:00 Address of the Holy Father Angelus [Italian] Sunday, 27 July 2014 Video Saint Peter's Square, at 12:00 Address of the Holy Father Angelus [Arabic, English, French, Italian, Portuguese] CALENDAR 2014 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL MAY JUNE JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER JANUARY 2014 1st Wednesday Booklet for the Celebration Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God Message of His Holiness Francis for the 47th World Day for Peace celebration of the XLVII World Day of Peace Vatican Basilica, at 10:00 2014: Fraternity, the Foundation and PAPAL MASS Pathway to Peace 2 [Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish] Holy Mass Video Photo Gallery Homily of the Holy Father [Arabic, Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish] Video Saint Peter's Square, at 12:00 Address of the Holy Father Angelus [Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish] 3 Friday Video Church of the Gesù (Rome), at 9:00 Homily of the Holy Father Holy Mass presided over by Pope Francis [English, French, German, Italian, Spanish] 5 Sunday Video Saint Peter's Square, at 12:00 Address of the Holy Father Angelus [Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish] Booklet for the Celebration 6 Monday Video Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord Photo Gallery Vatican Basilica, at 10:00 Homily of the Holy Father PAPAL MASS -

Getting the Poor Down from the Cross: a Christology of Liberation

GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation International Theological Commission of the ECUMENICAL ASSOCIATION OF THIRD WORLD THEOLOGIANS EATWOT GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation José María VIGIL (organizer) International Teological Commission of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians EATWOT / ASETT Second Digital Edition (Version 2.0) First English Digital Edition (version 1.0): May 15, 2007 Second Spanish Digital Edition (version 2.0): May 1, 2007 Frist Spanish Digital Edition (version 1.0): April 15, 2007 ISBN - 978-9962-00-232-1 José María VIGIL (organizer), International Theological Commission of the EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians, (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo). Prologue: Leonardo BOFF Epilogue: Jon SOBRINO Cover & poster: Maximino CEREZO BARREDO © This digital book is the property of the International Theological Commission of the Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT/ ASETT) who place it at the disposition of the public without charge and give permission, even recommend, its sharing, printing and distribution without profit. This book can be printed, by «digital printing», as a professionally formatted and bound book. Software can be downloaded from: http://www.eatwot.org/TheologicalCommission or http://www.servicioskoinonia.org/LibrosDigitales A 45 x 65 cm poster, with the design of the cover of the book can also be downloaded there. Also in Spanish, Portuguese, German and Italian. A service of The International Theological Commission EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo) CONTENTS Prologue, Getting the Poor Down From the Cross, Leonardo BOFF . -

Chapter 14 Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite A

CHAPTER 14 EXTRAORDINARY FORM OF THE ROMAN RITE A. INTRODUCTION 14.1.1 The Roman Missal promulgated in 1970 by Pope Paul VI is the ordinary expression of the lex orandi of the Catholic Church of the Latin rite. Nonetheless, it is permissible to celebrate the sacrifice of the Mass following the typical edition of the Roman Missal promulgated by Blessed Pope John XXIII in 1962 as an extraordinary form of the liturgy of the Church.1507 14.1.2 It is permissible as well, in the circumstances described below, to use the liturgical books promulgated or in use in 1962 for the celebration of some of the other sacraments and rites.1508 14.1.3 In addition to the Roman Missal, the liturgical books promulgated or in use in 1962 were the following: a. the Roman Breviary, in the typical edition of 1962; b. the Roman Martyrology; c. the Roman Ritual, in the typical edition of 1952, and local rituals derived from it;1509 1507 SP 1. It is not clear what “never abrogated,” used in the full text of this article in reference to the MR1962, means; for if the Missal was “never abrogated,” the law requiring its use certainly was. “Paul VI’s 1969 apostolic constitution Missale Romanum, was properly promulgated as law in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, in keeping with canon 9 of the 1917 code. The constitution required the use of the newly revised Roman Missal and abrogated previous law that had required use of the Tridentine rite Mass. The Pope decreed that his constitution had the force of law ‘now and in the future,’ and he expressly revoked contrary law, including ‘the apostolic constitutions and ordinances issued by our predecessors and other prescriptions, even those deserving of special mention and amendment.’ Moreover, the March 26, 1970, decree of the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship promulgating the editio typica of the revised Roman Missal contained the phrase, ‘Anything to the contrary notwithstanding.’” For a priest lawfully to use MR1962, even in private, an indult or permission of the ordinary was required.