Francesco Zavatti: Appealing Locally for Transnational Humanitarian Aid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

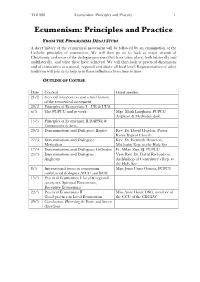

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 1994 The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Thomas P. “The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory,” Mid-Stream 33 (1994): 275-288. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas P. Rausch The Promise of the ew Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch, S. J., is Professor of Theological Studies and Rector of the Jesuit Community at Loyola Marym01.1nt University, Los Angeles, California, and chair of the department. A specialist in the areas of ecclesiology, ecumenism, and the theology of the priesthood, he is the author of five books and numerous articles. he new Roman Catholic Ecumenical Directory (ED), officially titled the Directory for the Application ofPrinciples and Norms on Ecumenism, was released on June 8, 1993 by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. 1 In announcing it, Pope John Paul II said that its preparation was motivated by "the desire to hasten the journey towards unity, an indispensable condition for a truly re newed evangelization. "2 The pope's linking of Christian unity with a renewal of the Church's work of evangelization is important, for the very witness of the Church as a community of humankind reconciled in Christ is weakened by the obvious lack of unity among Christians. -

Settore Assistenza Sociale Registro Regionale Del Volontariato 1 / 87

Settore Assistenza Sociale Registro Regionale del Volontariato aggiornato al 6 MAGGIO 2016 1 - IPOTENUSA 12 - A.V.O. Via Raffaele Mauri c/o UMA Via Sannitica SALERNO (SA) PIEDIMONTE MATESE (CE) Decreto n. 16010 del 06 dicembre 1993 Decreto n. 17323 del 29 dicembre 1993 2 - LOTTA TUMORI AL SENO 13 - CONFRATERNITA DI MISERICORDIA Corso Umberto I, 35 Via Municipio, 15 NAPOLI (NA) CASTELVETERE IN VAL FORTORE (BN) Decreto n. 16011 del 06 dicembre 1993 Decreto n. 17324 del 29 dicembre 1993 3 - CONFRATERNITA FRATERNITA' DI 14 - CONFRATERNITA DI MISERICORDIA MISERICORDIA Via Capogiardino Via Pianodardine - Scuola Media Statale R. Masi CASTELFRANCI (AV) ATRIPALDA (AV) Decreto n. 17325 del 29 dicembre 1993 Decreto n. 16012 del 06 dicembre 1993 15 - A.V.D.A. " LO SCIVOLO " 4 - CONFRATERNITA DI MISERICORDIA DI SAN Viale delle Rose, n.1 BARTOLOMEO IN GALDO CICCIANO (NA) P.zza MUNICIPIO, 7 Decreto n. 17326 del 29 dicembre 1993 SAN BARTOLOMEO IN GALDO (BN) 16 - BANCARELLA Decreto n. 16013 del 06 dicembre 1993 Contrada Grottareale 5 - LA SOLIDARIETA' ACERRA (NA) Piazza Umberto I Decreto n. 17327 del 29 dicembre 1993 FISCIANO (SA) 17 - KOINE' -INSIEME CON L'AMMALATO- Decreto n. 16824 del 20 dicembre 1993 Via Maria Longo, 50 6 - MO.V.I. FEDERAZIONE PROVINCIALE DI NAPOLI (NA) NAPOLI Decreto n. 17328 del 29 dicembre 1993 Via Bussola, n.5 18 - CENTRO ANIMAZIONE MISSIONARIA NAPOLI (NA) (C.A.M,) Decreto n. 16995 del 22 dicembre 1993 via G. Marconi, 203 7 - CRISTO E' LA RISPOSTA II PARETE (CE) Via Provinciale, 1 Quaglietta Decreto n. 3331 del 30 marzo 1994 CALABRITTO (AV) 19 - FRATERNITA DI MISERICORDIA " S. -

Pdf (Accessed January 21, 2011)

Notes Introduction 1. Moon, a Presbyterian from North Korea, founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity in Korea on May 1, 1954. 2. Benedict XVI, post- synodal apostolic exhortation Saramen- tum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), http://www.vatican.va/holy _father/benedict_xvi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi _exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis_en.html (accessed January 26, 2011). 3. Patrician Friesen, Rose Hudson, and Elsie McGrath were subjects of a formal decree of excommunication by Archbishop Burke, now a Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signa- tura (the Roman Catholic Church’s Supreme Court). Burke left St. Louis nearly immediately following his actions. See St. Louis Review, “Declaration of Excommunication of Patricia Friesen, Rose Hud- son, and Elsie McGrath,” March 12, 2008, http://stlouisreview .com/article/2008-03-12/declaration-0 (accessed February 8, 2011). Part I 1. S. L. Hansen, “Vatican Affirms Excommunication of Call to Action Members in Lincoln,” Catholic News Service (December 8, 2006), http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0606995.htm (accessed November 2, 2010). 2. Weakland had previously served in Rome as fifth Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation (1967– 1977) and is now retired. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2009). 3. Facts are from Bruskewitz’s curriculum vitae at http://www .dioceseoflincoln.org/Archives/about_curriculum-vitae.aspx (accessed February 10, 2011). 138 Notes to pages 4– 6 4. The office is now called Vicar General. 5. His principal consecrator was the late Daniel E. Sheehan, then Arch- bishop of Omaha; his co- consecrators were the late Leo J. -

The 'Enemy Within' the Post-Vatican II Roman Catholic Church

Page 1 of 8 Original Research The ‘enemy within’ the post-Vatican II Roman Catholic Church Author: The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) is regarded as one of the most significant processes Graham A. Duncan1 in the ecumenical church history of the 20th century. At that time, a younger generation of Roman Catholic theologians began to make their mark in the church and within the ecumenical Affiliation: 1Department of Church theological scene. Their work provided an ecumenical bridge between the Reforming and the History and Church Polity, Roman Catholic ecclesiastical traditions, notwithstanding the subsequent negative response University of Pretoria, of the Roman church hierarchy. Despite important advances, recent pontificates significantly South Africa altered the theological landscape and undermined much of the enthusiasm and commitment Correspondence to: to unity. Roman Catholic theological dissent provided common ground for theological Graham Duncan reflection. Those regarded as the ‘enemy within’ have become respected colleagues in the search for truth in global ecclesiastical perspective. This article will use the distinction between Email: the history and the narratives of Vatican II. [email protected] Postal address: Faculty of Theology, Introduction University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa The second Vatican Council (1962–1965) was a theological watershed for the Roman Catholic Church. Despite valiant attempts by the Curial administration to maintain rigid continuity with Dates: the past, a new generation of theologians emerged which represented the aggiornamento that Received: 06 Jan. 2013 Accepted: 30 Mar. 2013 Pope John XXIII so earnestly desired. This group was at the forefront of providing grounds for a Published: 31 May 2013 rapprochement with Reforming theology. -

Vassula Ryden Press Release

Vassula Ryden Press Release http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/CDFRYDN2.HTM NOTIFICATION ON VASSULA RYDEN (Dec 1996) Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (This clarification of its original Notification on Vassula Ryden was released to the Press in December 1996) I. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has received various questions about the value and authority of its Notification of 6 October 1995, published in L'Osservatore Romano on Monday/Tuesday, 23/24 October 1995, p. 2 (L'Osservatore Romano English edition, 25 October 1995, p. 12), regarding the writings and messages of Mrs. Vassula Ryden attributed to alleged revelations and disseminated in Catholic circles throughout the world. In this regard, the Congregation wishes to state: 1) The Notification addressed to the Pastors and faithful of the Catholic Church retains all its force. It was approved by the competent authorities and will be published in Acta Apostolicae Sedis, the official organ of the Holy See, with the signatures of the Prefect and the Secretary of the Congregation. [*] 2) Regarding the reports circulated by some news media concerning a restrictive interpretation of this Notification, given by His Eminence the Cardinal Prefect in a private conversation with a group of people to whom he granted an audience in Guadalajara, Mexico, on 10 May 1996, the same Cardinal Prefect wishes to state: a) as he said, the faithful are not to regard the messages of Vassula Ryden as divine revelations, but only as her personal meditations; b) these meditations, as the Notification explained, include, along with positive aspects, elements that are negative in the light of Catholic doctrine; c) therefore, Pastors and the faithful are asked to exercise serious spiritual discernment in this matter and to preserve the purity of the faith, morals and spiritual life, not by relying on alleged revelations but by following the revealed Word of God and the directives of the Church's Magisterium. -

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sources .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Worship Services .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Norms of Reciprocity and Collaboration .................................................................................................................... 5 Sharing in Non‐Sacramental Liturgical Worship ...................................................................................................... 6 Ecumenical Services ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Interfaith Services .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Sharing in God’s Word in Sacred Scripture ................................................................................................................ 7 Sacramental Celebrations ............................................................................................................................................. -

History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity

History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. by Philip Schaff About History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. by Philip Schaff Title: History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc7.html Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian CLassics Ethereal Library First Published: 1882 Print Basis: Second edition, revised Source: Electronic Bible Society Date Created: 2002-11-27 Contributor(s): whp (Transcriber) Wendy Huang (Markup) CCEL Subjects: All; History; LC Call no: BR145.S3 LC Subjects: Christianity History History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Philip Schaff Christianity. The German Reformation. Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii History of the Christian Church. p. 1 Preface. p. 2 Orientation. p. 3 The Turning Point of Modern History. p. 3 Protestantism and Romanism. p. 4 Necessity of a Reformation. p. 7 The Preparations for the Reformation. p. 9 The Genius and Aim of the Reformation. p. 10 The Authority of the Scriptures. p. 12 Justification by Faith. p. 14 The Priesthood of the Laity. p. 16 The Reformation and Rationalism. p. 17 Protestantism and Denominationalism.. p. 26 Protestantism and Religious Liberty. p. 31 Religious Intolerance and Liberty in England and America. p. 42 Chronological Limits. p. 50 General Literature on the Reformation. p. 51 LUTHER©S TRAINING FOR THE REFORMATION, A.D. L483-1517. p. 55 Literature of the German Reformation. p. 55 Germany and the Reformation. p. 57 The Luther Literature. p. -

'Il Y a Des Larmes Dans Leurs Chiffres': French Famine Relief for Ireland, 1847-84

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XIX-2 | 2014 La grande famine en irlande, 1845-1851 ‘Il y a des larmes dans leurs chiffres’: French Famine Relief for Ireland, 1847-84 « Il y a des larmes dans leurs chiffres » : L’assistance alimentaire française à l’Irlande, 1847-1884 Grace Neville Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic version URL: http://rfcb.revues.org/261 Printed version DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.261 Date of publication: 1 septembre 2014 ISSN: 2429-4373 Number of pages: 67-89 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Grace Neville, « ‘Il y a des larmes dans leurs chiffres’: French Famine Relief for Ireland, 1847-84 », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XIX-2 | 2014, Online since 01 May 2015, connection on 01 October 2016. URL : http://rfcb.revues.org/261 ; DOI : 10.4000/rfcb.261 The text is a facsimile of the print edition. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. ‘Il y a des larmes dans leurs chiffres’: French Famine Relief for Ireland, 1847-84 Grace NEVILLE University College Cork, National University of Ireland In July 1934, near the little County Cork village of Araglin, an elderly farmer, Michael Donegan, in conversation with a collector from the Irish Folklore Commission, illustrated the cruelty of a local landlord, Collins, with the following anecdote: In the famine times 1847 there was fourteen barrels of biscuits thrown out in the dung at his place and the people starving with hunger around the place. -

Centro Documentale Dell'isola Di Capri - Catalogo Per Autore

CENTRO DOCUMENTALE DELL'ISOLA DI CAPRI - CATALOGO PER AUTORE 08-nov-19 COLLOCAZIONE TESTO AUTORE TITOLO DIGITALE AB ALLHEMS TRYCKERIER AXEL MUNTHE SAN MICHELE 1576 ABBATE GIANNI, CARILLO SAVERIO E D'APRILE MARINA LUCI E OMBRE DELLA COSTA DI AMALFI 1269 ACOCELLA GIUSEPPE IL CATECHISMO REPUBBLICANO DI MICHELE NATALE VESCOVO DI VICO EQUENSE 434 ACTON HAROLD I BORBONI DI NAPOLI (1734-1825) 2418 ADELSON GALLERIES, INC. SARGENT'S WOMEN 1289 ADELWARD VIVEKA PEROT JACQUES JACQUES D'ADELSWARD FERSEN - L'INSOUMIS DE CAPRI 2540 ADLER KARLSSON GUNNAR RIFLESSIONI SULLA SAGGEZZA OCCIDENTALE 662 ADLER KARLSSON GUNNAR WESTWRN WISDOM 1460 ADLER KATHLEEN A CURA DI RENOIR 1825 AGNES BARBER CAPRI UND DER GOLF VON NEAPEL 1559 AGNES BARBER CAPRI UND DER GOLF VON NEAPEL 1559 AGNESE GINO BOCCIONI DA VICINO 1952 AKADEMISCHE STUDIENREISEN LOGBUCH EINER INTERESSANTEN REISE 1571 Al Idrisi Il Libro di Ruggero 0 ALBANESE GIOVANNI LA CHIESA E IL MONASTERO DEL SANTISSIMO SALVATORE A CAPRI 2304 ALBERINO ALISIA JEAN-JACQUES BOUCHARD A NAPOLI E A CAPRI NEL 1632 2459 ALBERINO FRANCESCO ANACAPRI CIVILIZZATO 1214 ALBERINO FRANCESCO LA PRESA DI CAPRI 146 ALBERTINI ALBERTO TRA EPOCHE OPPOSTE DIARIO CAPRESE 1943 - 1944 1736 ALDRICH ROBERT THE SEDUCTION OF THE MEDITERRANEAN 1902 ALEKSEJ LOZINA-LOZINSKIJ SOLITUDINE CAPRI E NAPOLI 2038 ALERAMO SIBILLA DIARIO DI UNA DONNA - TAGEBUCH EINER FRAU 1945 - 1960 1466 ALERAMO SIBILLA POESIE 1133 ALGRANATI GINA CANTI POPOLARI DELL' ISOLA D' ISCHIA 1577 ALINGS WIM JR CAPRI 2467 ALINOVI ABDON ROSSO POMPEIANO 2404 ALISIO GIANCARLO NAPOLI NEL SEICENTO - LE VEDUTE DI FRANCESCO CASSIANO DE SILVA D 195 1 COLLOCAZIONE TESTO AUTORE TITOLO DIGITALE ALISIO GIANCARLO A CURA DI CAPRI NELL'OTTOCENTO 163 ALISIO GIANCARLO A CURA DI CAPRI NELL'OTTOCENTO 65 ALISIO GIANCARLO a cura di KARL WILHELM DIEFENBACH 1951-1913 DIPINTI DA COLLEZIONI....