Battle of Prestonpans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterdean Wood

Butterdean Wood Butterdean Wood Management Plan 2018-2023 Butterdean Wood MANAGEMENT PLAN - CONTENTS PAGE ITEM Page No. Introduction Plan review and updating Woodland Management Approach Summary 1.0 Site details 2.0 Site description 2.1 Summary Description 2.2 Extended Description 3.0 Public access information 3.1 Getting there 3.2 Access / Walks 4.0 Long term policy 5.0 Key Features 5.1 Connecting People with woods & trees 5.2 Long Established Woodland of Plantation Origin 6.0 Work Programme Appendix 1: Compartment descriptions Appendix 2: Harvesting operations (20 years) Glossary MAPS Access Conservation Features Management 2 Butterdean Wood THE WOODLAND TRUST INTRODUCTION PLAN REVIEW AND UPDATING The Trust¶s corporate aims and management The information presented in this Management approach guide the management of all the plan is held in a database which is continuously Trust¶s properties, and are described on Page 4. being amended and updated on our website. These determine basic management policies Consequently this printed version may quickly and methods, which apply to all sites unless become out of date, particularly in relation to the specifically stated otherwise. Such policies planned work programme and on-going include free public access; keeping local people monitoring observations. informed of major proposed work; the retention Please either consult The Woodland Trust of old trees and dead wood; and a desire for website www.woodlandtrust.org.uk or contact the management to be as unobtrusive as possible. Woodland Trust The Trust also has available Policy Statements ([email protected]) to confirm covering a variety of woodland management details of the current management programme. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

RACELAND- Introduction

RACELAND- Introduction Proposal of Application Notice - Site Plan Introduction Land to North of A1 Gladsmuir Junction,Tranent Karting Indoors Ltd are proposing roadside services on land that is B 6 3 6 currently Raceland Karting. It is anticipated that an application for planning 3 permission in principle will be submitted to East Lothian Council later this year. On behalf of Karting Indoors Ltd, Clarendon Planning and Development Ltd submitted a Proposal of Application Notice (PAN ref 17/00002/PAN) Go-Kart Circuit to East Lothian Council for “Proposed Roadside Service Area comprising petrol filling station, ancillary class 1, class 3 and class 7 uses, parking, landscaping and associated infrastructure at Land To The North of A1 Communication Mast Gladsmuir Junction, Gladsmuir, Tranent, East Lothian”. A copy of the PAN site plan is provided in Figure 1. The PAN enables pre-application consultation with the council, the local community, and other interested 1 parties. A GLADSMUIR JUNCTION The purpose of this pre-application consultation event is to inform the 0m 25m 50m 75m Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. local community of the proposal for the site and to gain their views on Licence number 100022432. Plotted Scale - 1:2500 Clarendon Planning & Development Ltd the principle of the roadside services development. This consultation Figure 1 - PAN Site Plan event is designed to encourage meaningful discussion between members of the public and the appointed design team, so that the future design of the site can reflect local views, as far as possible. The Site Raceland Karting is located directly adjacent to the Gladsmuir Junction of the A1 (See Figure 2). -

Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from His

PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME XXIII SUPPLEMENT TO THE LYON IN MOURNING PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART ITINERARY AND MAP April 1897 ITINERARY OF PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART FROM HIS LANDING IN SCOTLAND JULY 1746 TO HIS DEPARTURE IN SEPTEMBER 1746 Compiled from The Lyon in Mourning supplemented and corrected from other contemporary sources by WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE With a Map EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1897 April 1897 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A List of Authorities cited and Abbreviations used ................................................................................. 8 ITINERARY .................................................................................................................................................. 9 ARRIVAL IN SCOTLAND .................................................................................................................. 9 LANDING AT BORRADALE ............................................................................................................ 10 THE MARCH TO CORRYARRACK .................................................................................................. 13 THE HALT AT PERTH ..................................................................................................................... 14 THE MARCH TO EDINBURGH ...................................................................................................... -

The Jacobites

THE JACOBITES Teacher’s Workshop Notes Timeline 1688 James II & VII overthrown; Stuarts go into exile 1701 James II & VII dies in France, his son becomes ‘James III & VIII’ in exile 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland; union of the parliaments 1708 James attempts to invade Scotland but fails to land 1714 George I becomes King of Great Britain 1715 Major Jacobite uprising in Scotland and northern England; James lands in Scotland but the rising is defeated 1720 Charles Edward Stuart “Bonnie Prince Charlie” born in Rome 1734 Charlie attends siege of Gaeta, his only military experience, at just 14 years old 1744 Charles is invited to France to head a French invasion of Britain which is then called off; Charles decides not to return home and plans to raise an army in Scotland alone 1745 23 Jul Charles lands in Scotland with just a few supporters 19 Aug Charles raises the Standard at Glenfinnan; 1200 men join him 17 Sept Charles occupies Edinburgh 21 Sept Battle of Prestonpans, surprise Jacobite victory 1 Nov Jacobite Army invades England 5 Dec Council of War in Derby forces Charles to retreat against his will 1746 17 Jan Confused Jacobite victory at the Battle of Falkirk; retreat continues 16 Apr Jacobites defeat at the Battle of Culloden 20 Sept Charles finally escapes from Scotland 1766 James III & VIII dies in Rome; Charles calls himself ‘King Charles III’ in exile 1788 Charles dies in Rome, in the house in which he was born The Jacobites The name Jacobite comes from the Latin form of James, Jacobus, and is the term given to supporters of three generations of exiled Royal Stuarts: James II of England & VII of Scotland, James III & VIII, and Charles Edward Stuart. -

Clan FARQUHARSON

Clan FARQUHARSON ARMS Quarterly, 1st & 4th, Or, a lion rampant Gules, armed and langued Azure (for Farquhar Shaw, descended from MacDuff, Earl of Fife); 2nd & 3rd, Argent, a fir tree growing out of a mount in base Vert, seeded Proper, on a chief Gules the Banner of Scotland displayed Or, and canton of the First charged with a dexter hand couped at the wrist fesswys holding a dagger point downwards of the Third CREST On a chapeau Gules furred Ermine, a demi-lion Gules holding in his dexter paw a sword Proper MOTTO Fide et fortitude (By fidelity and fortitude) On Compartment I force nae freen, I fear nae foe SUPPORTERS (on a compartment embellished with seedling Scots firs Proper) two wild cats guardant Proper STANDARD The Arms of Farquharson of Invercauld in the hoist and of two tracts Or and Gules, upon which is depicted a sprig of Scots fir Proper in the first and third compartments and the Crest, badgeways, in the second compartment, along with the Slughorn ‘Carn-na’cuimhne’ in letters Vert upon two transverse bands Argent PLANT BADGE Seedling Scots Firs Proper Farquharsons trace their origin back to Farquhar, fourth son of Alexander Cier (Shaw) of Rothiemurcus, who possessed the Braes of Mar near the source of the river Dee in Aberdeenshire. He descendants were called Farquharsons, and his son, Donald, married Isobel Stewart, heiress of Invercauld. Donald’s son, final Mor, was the real progenitor of the clan. The Gaelic patronymic is FacFionlaigh Mor. He was royal standard bearer at the Battle of Pinkie, where he was killed in 1547. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

NOTE of RELBUS MEETING Thursday, 13Th September 2012

NOTE OF RELBUS MEETING Thursday, 13 th September 2012, 7pm, Town House, Haddington Present: Barry Turner Chair Peter Armstrong East Lammermuir Community Councillor Michael Veitch East Lothian Councillor, Spokesperson for Transport Jacquie Bell Dunbar Community Councillor Philip Immirzi Sustaining Dunbar Morag Haddow Sustaining Dunbar Judy Miller Sustaining Dunbar Peter Hamilton Pencaitland Community Councillor Maureen Cuthill Macmerry & Gladsmuir Community Councillor Dougie Neill Macmerry & Gladsmuir Community Councillor Shena Jamieson Humbie,E&W Saltoun &Bolton Community Councillor David Rose Longniddry Community Councillor Item 1 – Apologies Colin Barnes, Barry Hutton, Ralph Averbuch and Councillors Berry and Caldwell Item 2 - Minutes of last meeting (21/6/12) Accepted Item 3 – Matters arising MV outlined his role as ELC Cabinet Spokesperson for Transport re. buses; has met with Perrymans and Prentice, and is soon to meet with Eve. These meetings have been very encouraging. ELC’s share of Lothian Buses will be used to influence the LB service and address the current two tier service in the county (east and west). Improving bus/bus and bus/train connectivity is also a priority. Item 4 – Update on LTS and action following Bus Conference LTS - Work is continuing on East Lothian Council’s Local Transport Strategy, which is included in the Council’s recently published 5 year plan. RELBUS to comment on LTS when this work is completed in the near future. Bus Conference - Nothing to report yet on results of bus conference, but outcomes will be fed into LTS. The follow up themes were:- • Spare capacity in voluntary sector provision; use of ELC green buses currently being reviewed to see if more efficient use could be made of them. -

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes Contents 1 Visiting the Exhibition 2 The Exhibition 3 Answers to the Trail Page 1 – Family Tree Page 2 – 1689 (James VII and II) Page 3 – 1708 (James VIII and III) Page 4 – 1745 (Bonnie Prince Charlie) 4 After your visit 5 Additional Resources National Museums Scotland Scottish Charity, No. SC011130 illustrations © Jenny Proudfoot www.jennyproudfoot.co.uk Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes 1 Introduction Explore the real story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the rise and fall of the Jacobites. Step into the world of the Royal House of Stuart, one dynasty divided into two courts by religion, politics and war, each fighting for the throne of thethree kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. Discover how four Jacobite kings became pawns in a much wider European political game. And follow the Jacobites’ fight to regain their lost kingdoms through five challenges to the throne, the last ending in crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Isle of Skye and onwards to Europe. The schools trail will help your class explore the exhibition and the Jacobite story through three key players: James VII and II, James VIII and III and Bonnie Prince Charlie. 1. Visiting the Exhibition (Please share this information with your adult helpers) Page Character Year Exhibition sections Important information 1 N/A N/A The Stuart Dynasty and the Union of the Crowns • Food and drink is not permitted 2 James VII 1688 Dynasty restored, Dynasty • Photography is not allowed and II divided, A court in exile • When completing the trail, ensure pupils use a pencil 3 James VIII 1708- The challenges of James VIII and III 1715 and III, All roads lead to Rome • You will enter and exit via different doors. -

GRAVEYARD MONUMENTS in EAST LOTHIAN 213 T Setona 4

GRAVEYARD MONUMENT EASN SI T LOTHIAN by ANGUS GRAHAM, M.A., F.S.A., F.S.A.SCOT. INTRODUCTORY THE purpos thif eo s pape amplifo t s ri informatioe yth graveyare th n no d monuments of East Lothian that has been published by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.1 The Commissioners made their survey as long ago as 1913, and at that time their policy was to describe all pre-Reformation tombstones but, of the later material, to include only such monuments as bore heraldic device possesser so d some very notable artisti historicar co l interest thein I . r recent Inventories, however, they have included all graveyard monuments which are earlier in date than 1707, and the same principle has accordingly been followed here wit additioe latey hth an r f eighteenth-centurno y material which called par- ticularly for record, as well as some monuments inside churches when these exempli- fied types whic ordinarile har witt graveyardsyn hme i insignie Th . incorporatef ao d trades othed an , r emblems relate deceasea o dt d person's calling treatee ar , d separ- n appendixa atel n i y ; this material extends inte nineteentth o h centurye Th . description individuaf o s l monuments, whic takee har n paris parisy hb alphan hi - betical order precedee ar , reviea generae y th b df w o l resultsurveye th f so , with observations on some points of interest. To avoid typographical difficulties, all inscriptions are reproduced in capital letters irrespectiv nature scripe th th f whicf n eo i eto h the actualle yar y cut. -

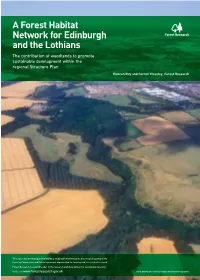

A Forest Habitat Network for Edinburgh and the Lothians the Contribution of Woodlands to Promote Sustainable Development Within the Regional Structure Plan

A Forest Habitat Network for Edinburgh and the Lothians The contribution of woodlands to promote sustainable development within the regional Structure Plan Duncan Ray and Darren Moseley, Forest Research This report has been prepared following a study by Forest Research, the research agency of the Forestry Commission and Britain’s principal organisation for forestry and tree-related research. Forest Research is a world leader in the research and development of sustainable forestry. Visit us at www.forestresearch.gov.uk Cover photograph – Patricia & Angus MacDonald/Aerographica Introduction The region of Edinburgh and the Lothians has about 22,000 hectares of Sustainable development woodland, representing 13% of the total land area. These woodlands Sustainable development is a popular are varied, comprising narrow shelterbelts, estate woodlands, ancient concept, and was famously articulated in woodland remnants in river gorge settings, and more recent conifer the Brundtland Report as “development plantations. Woodlands with high biodiversity are typically the which seeks to meet the needs and remnants of what was once a more extensive cover, but which has aspirations of the present without compromising the ability to meet the become fragmented over centuries due to changes in both type and needs of future generations”. This can pattern of land use. In particular, land has been cleared for only be achieved by development that agricultural use, which has accelerated over recent decades. Land has does not damage those resources also been lost to development, with the spread of settlements and essential for future generations. The transport infrastructure. As a result, there has been a general decline difficulty is that we cannot be certain which resources will become important in biodiversity over the wider countryside. -

Rebellious Scots to Crush to Scots Rebellious

Rebellious Scots cover 8/8/08 9:57 AM Page 1 Rebellious Scots to Crush Selected Johnston Paul Arran by Commentaries with Rebellious Arran Johnston, perhaps somewhat unexpectedly, is a specialist in political virtue in the late Roman Republic and early Principate, having recently completed his MA [Hons] in that field at Edinburgh University. His interest Scots to in the '45 has arisen from his involvement with the Charles Edward Stuart Society in home town Derby where, because of his youthfulness, he was invited to role play The Prince and as historian was determined to come to a greater Crush understanding. He met with the Battle of Prestonpans 1745 Heritage Trust activists in 2006 and has since then been a bold campaigner. He regularly plays The Prince at Prestonpans re-enactments and events. He is a broadcaster and public speaker both on Jacobite and Roman history and readily accepted the challenge of locating and commenting on the anthology presented here. £7.95 €12 $US15 + P&P Rebellious Scots to Crush ‘Prince Charles Edward Stuart’, attributed to Allan Ramsay (1713–84) This little-known portrait is attributed without certainty to the famous Scottish portraitist, whose impressive images of George III and David Hume are perhaps his best known. Even if not by Ramsay, the portrait seems to be a contemporary view of the Prince. His features are youthful and unthreatening, but his costume is of military theme, presenting the contrast of Charles’ young age and comparative inexperience with his dynamic ambitions and determined effort. Reproduced by kind permission of Derby Museum and Art Gallery.