The Temples of the Interfaces a Study of the Relation Between Buddhism and Hinduism at the Munnesvaram Temples, Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Musical Knowledge and the Vernacular Past in Post-War Sri Lanka

Musical Knowledge and the Vernacular Past in Post-War Sri Lanka Jim Sykes King’s College London “South Asian kings are clearly interested in vernacular culture zones has rendered certain vernacular Sinhala places, but it is the poet who creates them.” and Tamil culture producers in a subordinate fashion to Sinhala and Tamil ‘heartlands’ deemed to reside Sheldon Pollock (1998: 60) elsewhere, making it difficult to recognise histories of musical relations between Sinhala and Tamil vernac - This article registers two types of musical past in Sri ular traditions. Lanka that constitute vital problems for the ethnog - The Sinhala Buddhist heartland is said to be the raphy and historiography of the island today. The first city and region of Kandy (located in the central ‘up is the persistence of vernacular music histories, which country’); the Tamil Hindu heartland is said to be demarcate Sri Lankan identities according to regional Jaffna (in the far north). In this schemata, the south - cultural differences. 1 The second type of musical past ern ‘low country’ Sinhala musicians are treated as is a nostalgia for a time before the island’s civil war lesser versions of their up country Sinhala cousins, (1983-2009) when several domains of musical prac - while eastern Tamil musicians are viewed as lesser ver - tice were multiethnic. Such communal-musical inter - sions of their northern Tamil cousins. Meanwhile, the actions continue to this day, but in attenuated form southeast is considered a kind of buffer zone between (I have space here only to discuss the vernacular past, Tamil and Sinhala cultures, such that Sinhalas in the but as we will see, both domains overlap). -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

The Uluwahu Paenima (Crossing the Doorframe)

185 Appendix II: The Uluwahu Paenima (Crossing the Doorframe) Translation by Bonnie G. MacDougall Figure 43. Householders at entrance to courtyard, Rangama Sri Lanka. © 2008 Bonnie MacDougall, all rights reserved. A translation into English of the Uluwahu Paenima by Bonnie G. MacDougall. This document is part of the Cornell University eCommons MacDougall South Asian Architecture Collection and is available online at: [eCommons URI]. A scanned version of the original text is also available: http://hdl.handle.net/1813/8360. THE ULUWAHU PAENIMA PART I: SRI VISNU INVOCATION I beseech thee, O Resplendent Visnu, Lord of the Gods, who is also renown as Sankasila Deva Narayana,1 who is an aspirant to Buddhahood,2 who has protected Sri Lanka, the 2,000 islands, the four great continents of the world, the whole of the great Jambudvipa including its eighteen provinces, the great Buddhist church, the salt water circle of ocean that surrounds the land, and the four temples (devale) at the cardinal points. You who are descendant from Asuras and who dwell in the Vaikunta world3 and who ride the giant bird called Garuda. You who have become renown in this Kali age under such names as Lord Ada Visnu,4 Lord Mulu Visnu, Lord Demala Visnu, Lord Maha Visnu, Lord Sri Visnu and who have been manifest in the four Kali Ages in the ten incarnations5 including Rama (ramavatara)6 the Boar (vaerasara avatara), the Fish (mallawa avatara), Krisna (kirti avatara), the Tamil (demala avatara),7 the Gaja (tortoise) (gajavatara),8 the snake (naga avatara), the Buddha (bauddha avatara) and the 1The name of Visnu as reposing on the bed of the serpent between the creation and dissolution of the world. -

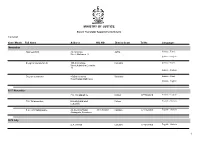

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Sri Pada': TRENDS in POPULAR BUDDHISM in SRI LANKA

GOD OF COMPASSION AND THE DIVINE PROTECTOR OF 'sRi pADA': TRENDS IN POPULAR BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA Introduction Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka has always coexisted with various forms of other religious practices oriented to deities, planets, astrology and demons (yakku), and some of these often figure in the Hindu tradition as well. However, the Buddhist doctrine in its canonical form stands apart from the culturally- specific forms of popular religious practices. Beliefs in gods and other supernatural powers and rituals are, in theory, inappropriate to be considered as part of Buddhism. But many anthropologists and sociologists who have spent extended periods of time in Theravada Buddhist societies have shown that Buddhists do believe in various types of supernatural powers and the magical efficacy of rituals which are outside the Buddhist doctrine. According to Obeyesekere (1962) astrology, gods and demon belief in 'Sinhala Buddhism' are guided by basic Buddhist principles such as karma, rebirth, suffering etc. So in that sense the practice of deity worship cannot be described as totally un- Buddhistic, yet at the same time it does not fall into the category of folk religious practices like bali and tovil adopted by popular Buddhism (see De Silva 2000, 2006). In Sri Lanka. there are four deities regarded as the guardians of the Buddha-sasana in the island: Vishnu, Saman, Kataragama, Natha and Pattini. Although Vishnu and Kataragama (Skanda) are originally Hindu gods, the Buddhists have taken them over as Buddhist deities, referring to them also by the localized designation, Uppalavanna and Kataragama. The role of Kataragama, Vi1inI1UNatha, and Pattini worship in the contemporary Sri Lankan society has been well researched by several scholars (e.g., Obeyesekere 1984; Holt 1991,2005; Gunasekara 2007) but the position of god Saman in the similar context has not been adequately investigated. -

21St October 1966 Uprising Merging the North and East Water and Big Business

December 2006 21st October 1966 Uprising SK Senthivel Merging the North and East E Thambiah Water and Big Business Krishna Iyer; India Resource Centre Poetry: Mahakavi, So Pa, Sivasegaram ¨ From the Editor’s Desk ¨ NDP Diary ¨ Readers’ Views ¨ Sri Lankan Events ¨ International Events ¨ Book Reviews The Moon and the Chariot by Mahaakavi "The village has gathered to draw the chariot, let us go and hold the rope" -one came forward. A son, borne by mother earth in her womb to live a full hundred years. Might in his arms and shoulders light in his eyes, and in his heart desire for upliftment amid sorrow. He came. He was young. Yes, a man. The brother of the one who only the day before with agility of mind as wings on his shoulder climbed the sky, to touch the moon and return -a hard worker. He came to draw the rope with a wish in his heart: "Today we shall all be of one mind". "Halt" said one. "Stop" said another. "A weed" said one. "Of low birth" said another. "Say" said one. "Set alight" said another. The fall of a stone, the slitting of a throat, the flight of a lip and teeth that scattered, the splattering of blood, and an earth that turned red. A fight there was, and people were killed. A chariot for the village to draw stood still like it struck root. On it, the mother goddess, the creator of all worlds, sat still, dumbfounded by the zealotry of her children. Out there, the kin of the man who only the day before had touched the moon is rolling in dirt. -

Second International Conference on Asian Studies 2014 PROCEEDINGS

Second International Conference on Asian Studies 2014 Colombo, Sri Lanka, 14th-15th July 2014 PROCEEDINGS ISBN 978-955-4543-22-5 Second International Conference on Asian Studies 2014 ICAS 2014 Sri Lanka ISBN 978-955-4543-22-5 Published by: International Center for Research and Development 858/6, Kaduwela Road, Thalangama North, Sri Lanka Email : [email protected] Web: www.theicrd.com © ICRD- July 2014 All rights reserved. 1 Second International Conference on Asian Studies 2014 ICAS 2014 Sri Lanka ICAS 2014 JOINT ORGANIZERS International Centre for Research and Development, Sri Lanka International University of Japan CO-CHAIRS Prof. N.S. Cooray, Japan Prabhath Patabendi, Sri Lanka HEAD OF THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Prof. Toshiichi Endo, Hong Kong International Scientific committee Prof. N. S. Cooray, Ph. D. (Japan) Prof. H. D. Karunaratna, Ph. D.( Sri Lanka) Prof. Toshiichi Endo, Ph. D.( Hong Kong) Prabhath Patabendi (ICRD ) Prof. Jai Pal Singhe, Ph. D.(India) Dr. Fiona Roberg (Sweden) Sun Tongquan, Ph.D. (China) Dr. Andrew Onwuemele, (Nigeria) Dr. Md. Jahirul Alam Azad (Bangladesh) Jasmin P. Suministrado (Philippines) R. L. Strrat, Ph.D. ( Netherland) Yuka Kawano, Ph.D. (Japan) Dr. Ting Wai Fong, (Hong Kong) Prof. (SMT.) T. Jaya Manohar (India) 2 Second International Conference on Asian Studies 2014 ICAS 2014 Sri Lanka Suggested citation DISCLAIMER: All views expressed in these proceedings are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the Institute of International Center for Research & Development , Sri Lanka and International University of Japan. The publishers do not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. -

Kartikeya - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

קרטיקייה का셍तिकेय http://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/k%C4%81rtikeya/index.html का셍तिकेय كارتِيكيا کارتيکيا تک ہ का셍तिकेय کا ر یی http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx Kartikeya - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartikeya Kartikeya From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Kartikeya (/ˌkɑrtɪˈkeɪjə/), also known as Skanda , Kumaran ,Subramanya , Murugan and Subramaniyan is Kartikeya the Hindu god of war. He is the commander-in-chief of the Murugan army of the devas (gods) and the son of Shiva and Parvati. Subramaniyan God of war and victory, Murugan is often referred to as "Tamil Kadavul" (meaning "God of Tamils") and is worshiped primarily in areas with Commander of the Gods Tamil influences, especially South India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Reunion Island. His six most important shrines in India are the Arupadaiveedu temples, located in Tamil Nadu. In Sri Lanka, Hindus as well as Buddhists revere the sacred historical Nallur Kandaswamy temple in Jaffna and Katirk āmam Temple situated deep south. [1] Hindus in Malaysia also pray to Lord Murugan at the Batu Caves and various temples where Thaipusam is celebrated with grandeur. In Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, Kartikeya is known as Subrahmanya with a temple at Kukke Subramanya known for Sarpa shanti rites dedicated to Him and another famous temple at Ghati Subramanya also in Karnataka. In Bengal and Odisha, he is popularly known as Kartikeya (meaning 'son of Krittika'). [2] Kartikeya with his wives by Raja Ravi Varma Tamil காத -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10