The Linden Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

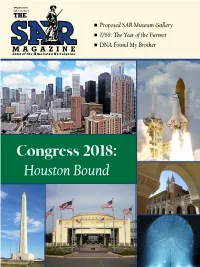

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Gist Family of South Carolina and Its Mary Land .Antecedents

The Gist Family of South Carolina and its Mary land .Antecedents BY WILSON GEE PRIVATELY PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY JARMAN'S, INCORPORATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 1 9 3 4 To THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHER PREFACE Among the earliest impressions of the author of this gen ealogical study are those of the reverence with which he was taught to look upon the austere to kindly faces in the oil portrai~ of his Gist ancestors as they seemed from their vantage points on the walls of the room to follow his every movement about the parlor of his boyhood home. From his mother, her relatives, his father, and others of the older people of Union County and the state of South Carolina,_ he learned much of the useful and valorous services rendered by this family, some members of which in almost each gen eration have with varying degrees of prominence left their mark upon the pages of history in times of both peace and war. Naturally he cherished these youthful impressions concerning an American family which dates far back into the colonial days of this republic. As he has grown older, he has collected every fragment of authentic material which he could gather about them with the hope that they might be some day permanently preserved in such a volume as this. But it is correct to state that very likely this ambition would never have been realized had not his cousin, Miss Margaret Adams Gist of York, South Carolina, who for thirty-five years or more has been gathering materials on the Gist family, generously decided to turn over to him temporarily for hi~ use her rich collections of all those years. -

Brooklyn, New York

HOLY NAME OF JESUS CHURCH WINDSOR TERRACE BROOKLYN, NEW YORK Fr. Lawrence D. Ryan, Pastor Mrs. Ann Dolan, Parish Trustee Deacon Abel Torres Mr. Philip Lehpamer, Parish Trustee Deacon Michael Saez Mrs. Kathryn Sisto, Religious Education Coordinator Rev. Austin Emeh, In Residence Ms. Ivonne Rojas, Director of Music Rev. Patrick Burns, In Residence St. Joseph the Worker Catholic Academy REV. Msgr. Michael J. Curran, Weekend Assistant Ms. Kathleen Schneck, Principal Mrs. Louise O’Connor, Office Manager Ms. Jennifer Gallina, Assistant Principal Mrs. Louise Witthohn, Academy Secretary Website: www.holynamebrooklyn.com We are also on Facebook and Twitter SUNDAY EUCHARIST - MISA DOMINICALES THE SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION - PENITENCIA Saturday: 5:30pm. Saturday: 4:00 to 5:00 pm. Sunday: 7:30, 9:00 (Spanish), 10:30am &12:00 Noon DEVOTIONS - DEVOCIONES WEEKDAY EUCHARIST - MISAS DE LA SEMANA Miraculous Medal Novena: Mondays after the 9:00am mass. Monday thru Friday: 9:00am. Sacred Heart: Fridays after the 9:00am mass. Saturday: 9:00am. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament:Thursdays 9:30am to Holidays: as announced in this bulletin. 11:45 am followed by Benediction. BAPTISM OF INFANTS LOS BAUTISMOS DE INFANTES. Is celebrated on the first Sunday of the month at 1:30 pm. Span- Seran celebrados en Espanol el Segundo Domingo del mes a la ish baptisms are celebrated on the second Sunday of the month 1:30 pm y en ingles, el primer Domingo del mes a la 1:30 pm. at 1:30 pm. Please call the Rectory to make an appointment to Por favor de, llamar a la rectoría para hacer una cita con un meet with one of the clergy and bring the child’s birth certificate miembro del clero y, de traer el certificado de nacimiento del to the appointment. -

Battle of White Plains Roster.Xlsx

Partial List of American Officers and Soldiers at the Battle of White Plains, October 28 - November 1, 1776 Name State DOB-DOD Rank Regiment 28-Oct Source Notes Abbot, Abraham MA ?-9/8/1840 Capt. Blake Dept. of Interior Abbott, Seth CT 12/23/1739-? 2nd Lieut. Silliman's Levies (1st Btn) Chatterton Hill Desc. Of George Abbott Capt. Hubble's Co. Abeel, James NY 5/12/1733-4/20/1825 Maj. 1st Independent Btn. (Lasher's) Center Letter from James Abeel to Robert Harper Acker, Sybert NY Capt. 6th Dutchess Co. Militia (Graham's) Chatterton Hill Acton 06 MA Pvt. Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of LostConcord art, sent with wounded Acton 07 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 08 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 09 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 10 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 11 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 12 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 13 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Acton 14 MA Eleazer Brooks's Regiment Chatterton Hill Shattuck's 1835 History of Concord Adams, Abner CT 11/5/1735-8/5/1825 Find a Grave Ranger for Col. Putnam Adams, Abraham CT 12/2/1745-? Silliman's Levies (1st Btn) Chatterton Hill Rev War Rcd of Fairfield CTCapt Read's Co. -

The Haversack the Newsletter of the Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

Vol. 3 Issue 4 September, 2016 The Haversack The Newsletter of the Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution st President’s Report meeting. Both 1 Vice President Pat Barron and 2nd Vice President Eugene Moyer are working dil- Greetings Compatriots: igently to produce a wonderful program that will, I’m very pleased to announce that our Chapter’s without a doubt, be interesting and enjoyable for partnership building and planning efforts for our all. very first social meeting with Maryland’s Lieuten- Donald A. Deering ant Governor Boyd K. Rutherford resulted in a President huge success. Approximately 100 attendees from Foundation Chair various businesses, local government, private non- Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter profits and other organizations attended to meet the Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Lt. Governor and learn of Maryland’s proposals Revolution for growth and economic development. As an add- National Society of the Sons of the American ed highlight, the Lieutenant Governor was intro- Revolution duced by Maryland State Secretary of Veteran’s Affairs, George W. Ownings III, who, along with his son and two grandsons, was recently inducted 2016 SEMI-ANNUAL MEETING as an SAR member. We were also pleased to wel- come Frederick’s very first County Executive “Jan Gardner” who offered a brief presentation prior to The semi-annual meeting of the Sergeant Law- the Secretary’s introduction. rence Everhart chapter will be held at Dutch’s Daughter restaurant on Thursday, October 20, Our partners in this endeavor, who we hope to 2016, beginning with a social hour at 6:00 PM. -

Fort Greene Park Prospect Park

Page 2 New York City Department of Parks & Recreation's Page 2 Fort Greene Park Prospect Park Fort Greene Historic Walking Tours &/or History Programs All programs meet outside the Audubon Center. Every Saturday at 1 p.m. * 06/14 tour starts at noon Sat, 6/15, 11 a.m. – Father’s Day Fishing – Bring Dad out to the park for an afternoon of fishing with Sun, 6/08, 12 p.m. – Nuts about Squirrels- Enjoy a fun the kids. Poles and bait will be provided. afternoon learning about those nutty creatures. Sat, 6/21, 11 a.m.- Canoe the Lullwater- Join the Sat, 6/14, 12 p.m. - Fort Green Neighborhood Walking Rangers for canoeing . Arrive early; first come first Tour- Explore the rich history and architecture of this served. Canoe times to sign up for: 11 a.m., 12:30 p.m. historic district. Wear comfortable walking shoes. or 2 p.m. Sign-up starts at 10:30 a.m. Sun, 6/15, 1 p.m. – Fort Greene Trivia- Join us as we answer some great questions about the Park. What’s the Sun, 6/22, 12 p.m.- Explore the Ravine Hike- Join the tallest tree? How tall is the Monument? Urban Park Rangers for a guided walk through the Ravine. Sun, 6/22, 1 p.m. – History of Fort Greene-What’s so special about Fort Greene? How did it get it’s name? Sat, 6/28, 1 p.m.- Tree-mendous Walk- Join the Urban Come find out its history. Park Rangers for a guided tour of beautiful Prospect Park. -

The Builder Magazine December 1920 - Volume VI - Number 12

The Builder Magazine December 1920 - Volume VI - Number 12 MEMORIALS TO GREAT MEN WHO WERE MASONS GENERAL MORDECAI GIST BY BRO. GEO. W. BAIRD, P.G.M., DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MORDECAI GIST was born in Baltimore on the twenty-second of February, 1742, the anniversary of the birthday of Washington. His ancestors were wealthy and distinguished people whose names are often found in the annals of the French and Indian wars. Mordecai Gist was educated for an Episcopal clergyman, but on the outbreak of the War of the Revolution he joined the first company recruited in Maryland, and became its Captain. In 1776 he was promoted to Major of a Maryland Battalion which was prominent in the battle of Long Island. He saw considerable service in the North, and was promoted to Brigadier General and commanded the Second Brigade of Maryland soldiers. In 1779 he was transferred to the South, and at the Battle of Camden, S.C., where De Kalb lost his life in 1780, he was conspicuous for valor and for splendid generalship. He was then assigned to recruiting and securing supplies and clothing for the Army, and was eminently successful in that trying time. This duty completed, he returned to the field and took part in the expulsion of the enemy from the Southern States, and was present at the siege and capture of Yorktown. He was, at that time, at the head of a Light Corps and rendered eminently effective service at that critical period of the war. He was accorded the credit of saving the day by a gallant charge in the Battle of Combahee. -

Maryland in the American Revolution

382-MD BKLT COVER fin:382-MD BKLT COVER 2/13/09 2:55 PM Page c-4 Maryland in the Ame rican Re volution An Exhibition by The Society of the Cincinnati Maryland in the Ame rican Re volution An Exhibition by The Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House Wash ingt on, D .C. February 27 – September 5, 2009 his catalogue has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition Maryland in the American Revolution on display fTrom February 27 to September 5, 2009, at Anderson House, the headquarters, library, and museum of The Society of the Cincinnati in Washington, D.C. The exhibition is the eleventh in a series focusing on the contributions to the e do most Solemnly pledge American Revolution made by the original thirteen states ourselves to Each Other and France. W & to our Country, and Engage Generous support for this exhibition and catalogue was provided by the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland. ourselves by Every Thing held Sacred among Mankind to Also available: Massachusetts in the American Revolution: perform the Same at the Risque “Let It Begin Here” (1997) of our Lives and fortunes. New York in the American Revolution (1998) New Jersey in the American Revolution (1999) — Bush River Declaration Rhode Island in the American Revolution (2000) by the Committee of Observation, Connecticut in the American Revolution (2001) Delaware in the American Revolution (2002) Harford County, Maryland Georgia in the American Revolution (2003) March 22, 1775 South Carolina in the American Revolution (2004) Pennsylvania in the American Revolution (2005) North Carolina in the American Revolution (2006) Text by Emily L. -

Brigades and Regiments -- Morristown Encampment of 1779-80

Brigades and Regiments -- Morristown Encampment of 1779-80 First Maryland Brigade Commander: Brigadier General William Smallwood 1st Maryland Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Peter Adams 3rd Maryland Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Nathaniel Ramsay 5th Maryland Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Thomas Woolford 7th Maryland Regiment Colonel John Gunby Second Maryland Brigade Commander: Brigadier General Mordecai Gist 2nd Maryland Regiment Colonel Thomas Price 4th Maryland Regiment Colonel Josias Carvil Hall 6th Maryland Regiment Colonel Otho Williams Hall’s Delaware Regiment Colonel David Hall First Connecticut Brigade Commander: Brigadier General Samuel Parsons rd 3 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Samuel Wyllys th 4 Connecticut Regiment Colonel John Durkee th 6 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Return Jonathan Meigs th 8 Connecticut Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Issac Sherman Second Connecticut Regiment Commander: Brigadier General Jedediah Huntington st 1 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Josiah Starr th 2 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Zebulon Butler th 5 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Philip B. Bradley th 7 Connecticut Regiment Colonel Heman Swift New York Brigade Commander: Brigadier General James Clinton nd 2 New York Regiment Colonel Philip VanCortland rd 3 New York Regiment Colonel Peter Gansevoort th 4 New York Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Fredrick Weissenfels th 5 New York Regiment Colonel Jacobus S. Bruyn Hand’s Brigade Commander: Brigadier General Edward Hand st 1 Canadian Regiment Colonel Moses Hazen nd 2 Canadian Regiment Colonel James Livingston th 4 Pennsylvanian Regiment Colonel William Butler th 11 Pennsylvanian Regiment Lt. Colonel Comd. Adam Hubley First Pennsylvania Brigade Commander: Brigadier General William Irvine st 1 Pennsylvania Regiment Colonel James Chambers nd 2 Pennsylvania Regiment Colonel Walter Stewart th 7 Pennsylvania Regiment Colonel Morgan Conner / Lt. -

Gen. Nathanael Greene's Moves to Force the British Into The

` The Journal of the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution ` Vol. 12, No. 1.1 January 23, 2015 Gen. Nathanael Greene’s Moves to Force the British into the Charlestown Area, to Capture Dorchester, Johns Island and to Protect the Jacksonborough Assembly November 1781 - February 1782 Charles B. Baxley © 2015 Fall 1781 – South Carolina The British Southern strategy was unraveling. Lt. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781. The British army of occupation in North and South Carolina and Georgia could hold selected posts and travel en masse at will, but could not control the countryside where rebel militias and state troops patrolled. Their southern strongholds were within 35 miles of their supply ports: Charlestown, Savannah and Wilmington, NC. In South Carolina the British withdrew from their advanced bases at Camden, Ninety Six, Augusta, and Georgetown, and only held posts arcing around Charlestown in the aftermath of the bloody battle at Eutaw Springs in September. Defending Charlestown, the British had major forward posts at Fair Lawn Barony (in modern Moncks Corner) at the head of navigation of the west branch of the Cooper River; at the colonial town of Dorchester at the head of navigation on the Ashley River; at the Wappataw Meeting House on the headwaters of the Wando River; and at Stono Ferry to control mainland access across the Stono River to Johns Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, 1783 Island. The parishes north of Charlestown were contested portrait by Charles Willson Peale, ground. British cavalry rode at will to the south side of the Independence National Historical Santee River and as far upstream as Pres. -

Battle of Long Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Long Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Long_Island Coordinates: 40°39′58″N 73°57′58″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Battle of Long Island is also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights. It was Battle of Long Island fought on August 27, 1776 and was the first major battle of Part of the American Revolutionary War the American Revolutionary War to take place after the United States declared its independence on July 4, 1776. It was a victory for the British Army and the beginning of a successful campaign that gave them control of the strategically important city of New York. In terms of troop deployment and fighting, it was the largest battle of the entire war. After defeating the British in the Siege of Boston on March 17, 1776, commander-in-chief General George Washington brought the Continental Army to defend the port city of New York, then limited to the southern end of Manhattan The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island Island. Washington understood that the city's harbor would Date August 27, 1776 provide an excellent base for the British Navy during the campaign, so he established defenses there and waited for Location Kings County, Long Island, New York the British to attack. In July, the British under the command 40°39′58″N 73°57′58″W of General William Howe landed a few miles across the Result British victory[1] harbor from Manhattan on the sparsely-populated Staten Island, where they were slowly reinforced by ships in Belligerents Lower New York Bay during the next month and a half, United States bringing their total force to 32,000 troops.