Lord Krishna’ in Swarajbir’S Krishan (2001): a Retelling of ‘Khandavadaha’ Incident

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4 Kisari Mohan Ganguli The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4, by Kisari Mohan Ganguli This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4 Author: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: April 16, 2004 [EBook #12058] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATAM, BK. 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare, Juliet Sutherland, David King, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 4 VIRATA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. THE MAHABHARATA VIRATA PARVA SECTION I (_Pandava-Pravesa Parva_) OM! Having bowed down to Narayana, and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and also to the goddess Saraswati, must the word _Jaya_ be uttered. Janamejaya said, "How did my great-grandfathers, afflicted with the fear of Duryodhana, pass their days undiscovered in the city of Virata? And, O Brahman, how did the highly blessed Draupadi, stricken with woe, devoted to her lords, and ever adoring the Deity[1], spend her days unrecognised?" [1] _Brahma Vadini_--Nilakantha explains this as _Krishna-kirtanasila._ Vaisampayana said, "Listen, O lord of men, how thy great grandfathers passed the period of unrecognition in the city of Virata. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11162-2 — an Environmental History of India Michael H

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11162-2 — An Environmental History of India Michael H. Fisher Index More Information Index Abbasi, Shahid, 239 Ali, Salim, 147, 181 Abbasid Caliphate, 81, 82, 87. See also Allahabad, 110 Islam; Muslims aloe trees, 58 Abu al-Fazl Allami, 97, 100 al-Qaeda, 234, 237 Acheulean culture, 22 Ambedkar, B.R., 155, 157 Addiscombe, East India Company military amber, 36 seminary, 133 America, 70, 130, 207. See also Columbian Adivasi,30–31. See also forest-dwellers Exchange; United States advaita (non-dualism), 45, 55 trade with, 78, 91–92, 102, 103, 114, 116 afforestation, 207, 210, 213, 229 Amritsar, 157, 159, 205. See also Punjab Afghanistan, 11, 16, 60, 64, 136, 213, 214. Andaman Islands, 24 See also South Asia, defined Anglicization, 129, 136, 137, 154, 156, 166 immigration from, 83, 85, 88, 94, 96 Anglo-Indians, 136, 142 Mughal period, 94, 109, 110, 113 animals. See by species Pakistan, relations, 163, 165, 168, antelope, 38, 51, 86, 103, 119 172–73, 234 Anthropocene, 19, 116 Africa, 13–14, 19 anupa (marshes), 52 European colonialism, 70, 78, 91, 154 apples, 126 immigration from, 22–23, 78–80, 91 aquifers, 1, 19, 118, 150, 151, 189, 191, Indians in, 154 240, 242–43. See also arsenic trade with, 65, 80, 81, 89, 91, 113 Arabia, 23, 78–82. See also Islam; Muslims Agarwal, Anil, 203 trade with, 39, 40, 81, 86, 89 agate, 36, 39 Arabian Sea, 45, 235 Agenda 21, 210, 224, 232. See also Rio Arabic, 20, 88, 95, 97, 100, 101, 125, Conference 213 Agha Khan Foundation, 231 Arakan, 109. -

D. D. Kosambi History and Society

D. D. KOSAMBI ON HISTORY AND SOCIETY PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETATION DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF BOMBAY, BOMBAY PREFACE Man is not an island entire unto himself nor can any discipline of the sciences or social sciences be said to be so - definitely not the discipline of history. Historical studies and works of historians have contributed greatly to the enrichment of scientific knowledge and temper, and the world of history has also grown with and profited from the writings in other branches of the social sciences and developments in scientific research. Though not a professional historian in the traditional sense, D. D. Kosambi cre- ated ripples in the so-called tranquil world of scholarship and left an everlasting impact on the craft of historians, both at the level of ideologi- cal position and that of the methodology of historical reconstruction. This aspect of D. D. Kosambi s contribution to the problems of historical interpretation has been the basis for the selection of these articles and for giving them the present grouping. There have been significant developments in the methodology and approaches to history, resulting in new perspectives and giving new meaning to history in the last four decades in India. Political history continued to dominate historical writings, though few significant works appeared on social history in the forties, such as Social and Rural Economy of North- ern India by A. N. Bose (1942-45); Studies in Indian Social Polity by B. N. Dutt (1944), and India from Primitive Communism to Slavery by S. A. Dange (1949). It was however with Kosambi’s An Introduction to the study of Indian History (1956), that historians focussed their attention more keenly on modes of production at a given level of development to understand the relations of production - economic, social and political. -

Agriculturists and the People of the Jungle: Reading Early Indian Texts

Vidyasagar University Journal of History, Volume III, 2014-2015 Pages 9-26 ISSN 2321-0834 Agriculturists and the People of the Jungle: Reading Early Indian Texts Prabhat Kumar Basant Abstract: Historians of early India have understood the transition from hunting-gathering to agriculture as a dramatic transformation that brought in its wake urbanism and state. Jungles are believed to have been destroyed by chiefs and kings in epic encounters. Does anthropology support such an understanding of the processes involved in the transition from hunting –gathering to agriculture? Is it possible that historians have misread early Indian texts because they have mistaken poetic conventions for a statement of reality? A resistant reading of the early Indian texts together with information from anthropology shows that communities of agriculturists, pastoral nomads and forest people were in active contact. Agriculturists located on the cultural or spatial margins of state societies colonised new areas for cultivation. Transition to agriculture was facilitated by the brahman-shramana tradition. Keywords: The Neolithic Revolution, Slash and burn cultivation, Burning of the Khandava forest, The Arthashastra, The Mahabharata, Jatakas, Kadambari. The history of India in the last five thousand years is a history of the expansion of agriculture. Anyone who has mapped archaeological sites over the last five thousand years will testify that though there are cases where the wild has made a comeback, the general trend has been that of conquest of the jungle by agriculturists. I wish to study the processes involved in the transition to agriculture in early India, though such studies are handicapped by lack of information in contemporary texts. -

Part 1: the Beginning of Mahabharat

Mahabharat Story Credits: Internet sources, Amar Chitra Katha Part 1: The Beginning of Mahabharat The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, a nymph of Indra's court, from sage Vishwamitra, who secretly fell in love with her. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. He ruled for many years and was the founder of the Kuru dynasty. Unfortunately, things did not go well after the death of Bharata and his large empire was reduced to a kingdom of medium size with its capital Hastinapur. Mahabharata means the story of the descendents of Bharata. The regular saga of the epic of the Mahabharata, however, starts with king Shantanu. Shantanu lived in Hastinapur and was known for his valor and wisdom. One day he went out hunting to a nearby forest. Reaching the bank of the river Ganges (Ganga), he was startled to see an indescribably charming damsel appearing out of the water and then walking on its surface. Her grace and divine beauty struck Shantanu at the very first sight and he was completely spellbound. When the king inquired who she was, the maiden curtly asked, "Why are you asking me that?" King Shantanu admitted "Having been captivated by your loveliness, I, Shantanu, king of Hastinapur, have decided to marry you." "I can accept your proposal provided that you are ready to abide by my two conditions" argued the maiden. "What are they?" anxiously asked the king. -

Dual Edition

YEARS # 1 Indian American Weekly : Since 2006 VOL 15 ISSUE 13 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAR 26 - MAR 25 - APR 01, 2021 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● [email protected] www.theindianpanorama.news THE INDIAN PANORAMA ADVT. FRIDAY MARCH 26, 2021 YEARS 02 We Wish Readers a Happy Holi YEARS # 1 Indian American Weekly : Since 2006 VOL 15 ISSUE 13 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAR 26 - MAR 25 - APR 01, 2021 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● [email protected] www.theindianpanorama.news VAISAKHI SPECIAL EDITIONS Will Organize Summit of will bring out a special edition tomarkVAISAKHIon April 9. Democracies, says Biden Advertisementsmay please be booked by April 2, andarticles for publication may please besubmitted by March 30 to [email protected] "We've got to prove democracy works," he said. I.S. SALUJA First historic Mars WASHINGTON (TIP): President Joe Biden shared with media persons his helicopter flight on April 8: thoughts on a wide range of issues, and NASA also candidly answered their questions, March 25, at his first press conference The flight since assuming office on January model of NASA's 20.2021. Ingenuity During the press conference, Mr. Mars Biden remarked on and responded to Helicopter - questions regarding migrants at the Image: NASA / JPL U.S.-Mexico border, the COVID-19 contd on page 48 WASHINGTON (TIP): NASA will U.S. President Joe Biden holds his first formal attempt to fly Ingenuity mini << news conference as president in the East helicopter, currently attached to the Room of the White House in Washington, U.S., belly of Perseverance rover, on Mars March 25, 2021. -

18. the Escape of Takshaka

Chapter 18. The Escape of Takshaka hen Vyasa yielded to his importunity, Parikshith who was all attention, replied in a voice that stuttered with Wemotion. “Master, I don’t see clearly why my grandfather destroyed the Khandava Forest with a fire. Tell me how Lord Krishna helped him in the exploit. Make me happy by telling me the story.” Parikshith fell at the sage’s feet and prayed that this may be described to him. Krishna and Arjuna meet hungry Fire God Vyasa complimented him and said, “Right, you have made a request that does you credit. I’ll comply.” “Once, when Krishna and Arjuna were resting happily on the sands of the Yamuna, oblivious of the world and its tangles, an aged brahmin approached them and said, ‘Son, I am very hungry. Give me a little food to ap- pease me. I can’t keep alive unless you do.’ “At these words, they were suddenly made aware of a strange presence. Though outwardly he appeared natu- ral, there was a divine effulgence around him, which marked him out as someone apart. “Krishna came forward and accosted him. ‘Great brahmin, you don’t appear merely human. I assume that you won’t be satisfied with ordinary food. Ask me what food you want, I’ll certainly give it you.’ “Arjuna stood at a distance watching this conversation with amazement. For, he heard Krishna, who allayed the hunger of all beings in all the worlds, asking this lean hungry brahmin, what food would satisfy him! Krishna was asking so quietly and with so much consideration that Arjuna was filled with curiosity and surprise. -

Srimad Bhagavatam, Volume 3 ALL GLORY to SRI GURU and GOURANGA Yasya Rastre Prajah Sarvas Trasyante Saddhi Asadhubhih Tasya Mattasya Nasyanti Kirtir Ayur Bhaga Gatih

Srimad Bhagavatam, Volume 3 ALL GLORY TO SRI GURU AND GOURANGA Yasya rastre prajah sarvas trasyante saddhi asadhubhih Tasya mattasya nasyanti kirtir ayur bhaga gatih. Esha rajnam paro dharmo hi artanam artinigrahah Ata enam vadhisyami bhutadroha asattamam (pp. 1023) SRIMAD BHAGWATAM of KRISHNA DWAIPAYANA VYAS ENGLISH VERSION (Third Volume) By A. C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI Vedanta & Srimad Bhagwatam Review by The Indian Philosophy & Culture, Vrindaban Quaterly Journal of the INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL PHILOSOPHY Vrindaban U.P. (INDIA) SEPTEMBER 1964 LIST OF OTHER BOOKS (In English) 1. GEETOPANISHAD. 2. CHAITANYA CHARITAMRITA ESSAYS AND TEXT. 3. SCIENCE OF DEVOTION. 4. EASY JOURNEY TO OTHER PLANETS. 5. PRACTICAL THEISM. 6. MESSAGE OF GODHEAD. 7. ISOPANISHAD. 8. PRAYERS OF KING KULASHEKHAR. Editor of THE FORTNIGHLY MAGAZINE BACK - TO - GODHEAD AND FOUNDER SECRETARY. THE LEAGUE OF DEVOTEES (Regd.) Residence:—Sri Radha Damodar Temple Sebakunja, Vrindaban U. P. Office:—Sri Radha Krishna Temple Post Box No. 1846 2439, Chhipiwada Kalan DELHI-6. Srimad Bhagavatam has been declared by Sri Caitanya as the only authentic commentary on the Brahma Sutram. It is well known that Bhagavan Vedavyasa compiled the different Vedas and the Upanisads, as also laid down the true import of the same by means of his aphorisms, known as Brahma Sutram. The Sutram being difficult. he further condescended to write the Bhagavatam in the form of Puranam with the object of making the teachings of theVedas, as laid down in the Brahma Sutram, an easy access. This shows the great importance of the Bhagavatam a work from the pen of the great compiler of the Vedas himself as the right key to the secret lore of the Vedas and the Upanisads, though it is not written in the style of an usual commentary on the Brahma Sutram. -

4. Protection of Forest in Ancient India

X3 4. PROTECTION OF FOREST IN ANCIENT INDIA 4.1. The Beginning of Deforestation With the introduction of agriculture in the Neolithic period, man began to exercise considerable influence on the plant life in India as elsewhere. With the growing population and increasing demand on the forests for a clearance of land for cultivation, for smelting copper and later on iron, for baking bricks and pottery, a tremendous destructive influnce in addition to climatic and edaphic changes, reduced the indigenous forests to a great extent The flourishing vegetation in Rajasthan and Sind was replaced by a desert about a couple of thousand years ago i. Excepting Rajasthan, no portion of india seems to have suffered from aridity or barrenness. Being situated within monsoon belt, almost all portions of this subcontinent could get sufficient rainfall which provided condition for the vigourous growth of forests. The history of forests in India like any other country in the world is one of deforestation. There are many natural causes for the destruction of large tracts of forests. Mention may be made to volcanic 2 action of great intensity, flood, fire and also to the meteoric showers • But man's responsibility for the destruction of forests is the greatest. From the starting mark of human civilization, man had to depend on the supplies of nature. For pastoral and agricultural land he had to clear off the jungles and trees. He had to cut down the trees for constructing houses and for gathering fuels. With the passage of time he came to learn how to use plants, herbs and the roots of some trees as drugs for curing various diseases. -

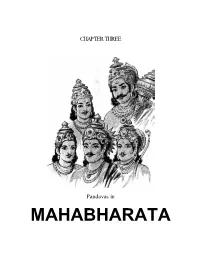

Year III-Chap.3-MAHABHARATA

CHAPTER THREE Pandavas in MAHABHARATA Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA CHANDRA VAMSA The first king of the race of the Moon was PURURAVAS His great grandson l KING YAYATI His sons l l l KING PURU KING YADU One of his descendants His descendants were called Yadavas l l KING DUSHYANT LORD KRISHNA His son l KING BHARATA – one of his descendants l KING KURU One of his descendants l KING SHANTANU His sons l l l l CHITRANGAD VICHITRAVIRYA BHEESHMA His sons l l l DHRITARASHTRA PANDU His 100 sons called after King Kuru as His five sons called after him as l l KAURAVAS PANDAVAS l Arjuna’s grandson KING PARIKSHIT 44 Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA MAHABHARATA Mahabharata is the longest epic poem in the world, originally written in Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. It was composed by Sage Veda Vyasa several thousand years ago. Vyasa dictated the entire epic at a stretch while Lord Ganesha wrote it down for him. The epic has been divided into the following: o ADI PARVA o SABHA PARVA o VANA PARVA o VIRATA PARVA o UDYOGA PARVA o BHEESHMA PARVA o DRONA PARVA o KARNA PARVA o SALYA PARVA / AFTER THE WAR ADI PARVA The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, an apsara (nymph) of Indra's court, and sage Vishwamitra. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. It was after his name India came to be known as Bharatavarsha. -

Krishna : a Sourcebook / Edited by Edwin F

Krishna This page intentionally left blank Krishna A Sourcebook Edited by edwin f. bryant 1 2007 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright Ó 2007 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Krishna : a sourcebook / edited by Edwin F. Bryant. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6; 978-0-19-514892-3 (pbk.) 1. Krishna (Hindu deity)—Literary collections. 2. Devotional literature, Indic. I. Bryant, Edwin. BL1220.K733 2007 294.5'2113—dc22 2006019101 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Contents Contributors, ix Introduction, 3 PART I Classical Source Material 1. Krishna in the Mahabharata: The Death of Karna, 23 Alf Hiltebeitel 2. Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita,77 Robert N. Minor 3. The Harivamsa: The Dynasty of Krishna, 95 Ekkehard Lorenz 4.