13 Galley-CORRECTIONS.Wps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Website Migrate Upgrade SLA Hosting Final

IMPENDLE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY TENDER NUMBER: ILM/SCM/Quotation/12/2021 WEBSITE MIGRATE Re-DESIGN & 36MONTHS TENTANT HOSTING FOR IMPENDLE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY CLOSING DATE AND TIME: 13 JANUARY 2021 @ 12H00 PM NAME OF ORGANISATION POSTAL ADDRESS CONTACT PERSON TELEPHONE NO. FAX NO. E-MAIL ADDRESS TENDER PRICE TABLE OF CONTENT ITEM NO. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. 1. Check List 3-4 2. Tender Advert 5-6 3. Tender Specification/ Scope of Work 7-13 4. Form of Offer and Acceptance 14-15 5. Invitation to Bid 16-18 6. Tax Clearance Certificate 19 7. Pricing Schedule 22 8. Declaration of Interest 21-23 9. Preference Points Claim Form 24-28 10. Local Content 29-32 11. Contract form for purchase of goods 33-34 12. Past Supply Chain Practices 36-36 13. Certificate of Independent Bid Declaration 37-39 14. Company Registration 40 15. Proof of municipal rates and taxes 41-43 16. BEE Certificate 44 17. CSD Registration 45 18. General Conditions of Tender 46-50 19. General Conditions of Contract 2010 51-61 Tenderers are advised to check the number of pages and should any be missing or duplicated, or the reproduction indistinct, or any descriptions ambiguous, or this document contain any obvious errors they shall inform the Impendle Municipality at once and have the same rectified. No liability whatsoever will be admitted in respect of errors in any tender due to the tenderers failure to observe this requirement. QUOTATION CHECKLIST PLEASE ENSURE THAT THE FOLLOWING FORMS HAVE BEEN DULY COMPLETED AND SIGNED AND THAT ALL DOCUMENTS AS REQUESTED, ARE ATTACHED TO THE TENDER DOCUMENT: Tenderer to Office Use No Description Tick ( ) Only 1. -

Page 01 March 13.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 22 SPORT | 36 Rajan wants global Uzma reigns rules of conduct supreme at for central banks Doha Golf Club SUNDAY 13 MARCH 2016 • 4 Jumada II 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6734 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Winning leap Emir receives call Al Kuwari slams from Kuwait Emir DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani received last destruction of evening a telephone call from Emir of Kuwait H H Sheikh Sabah Al Ahmad Al Jaber Al Sabah. heritage sites Emir congratulates Mauritius President DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim Emir’s Cultural bin Hamad Al Thani yesterday sent a cable of congratulations to the Advisor says pained President of Mauritius, Ameenah by Homs, Palmyra, Gurib-Fakim, on her country’s Aleppo, Mosul National Day, reports QNA. Dep- uty Emir H H Sheikh Abdullah bin and Nimrod. Hamad Al Thani sent a similar cable to the President of Mauritius. The Peninsula Emir sends message Action from the second leg of the QNB Doha Tour at the Main Arena of the Qatar Equestrian Federation to French President (QEF) in Al Rayyan yesterday. Qatari rider Faleh Suwead Al Ajami guided Armstrong Van De Kapel DOHA: H E Dr Hamad bin Abdulaziz to victory in the second leg while Saudi Arabia’s Abdullah Alsharbatly finished second followed by PARIS: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim Al Kuwari (pictured), Cultural Advi- affects mostly the Middle Eastern Qatar’s Ali Youseff Al Rumaihi. → See also page 29 bin Hamad Al Thani has sent a sor to Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin and Arab regions. -

AMNH Digital Library

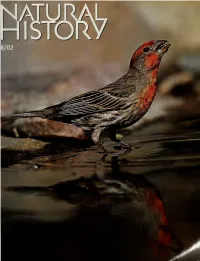

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis Zhi Gao1∗, Mo Shan2∗, Loong-Fah Cheong3, and Qingquan Li4,5 1 Interactive and Digital Media Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2 Temasek Laboratories, National University of Singapore 3 Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, National University of Singapore 4 The State Key Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping, and Remote Sensing, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China 5 Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Spatial Smart Sensing and Services, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China fgaozhinus, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Inspired by the outstanding performance of sparse coding in applications of image denoising, restoration, classification, etc, we pro- pose an adaptive sparse coding method for painting style analysis that is traditionally carried out by art connoisseurs and experts. Significantly improved over previous sparse coding methods, which heavily rely on the comparison of query paintings, our method is able to determine the au- thenticity of a single query painting based on estimated decision bound- ary. Firstly, discriminative patches containing the most representative characteristics of the given authentic samples are extracted via exploit- ing the statistical information of their representation on the DCT basis. Subsequently, the strategy of adaptive sparsity constraint which assigns higher sparsity weight to the patch with higher discriminative level is enforced to make the dictionary trained on such patches more exclu- sively adaptive to the authentic samples than via previous sparse coding algorithms. Relying on the learnt dictionary, the query painting can be authenticated if both better denoising performance and higher sparse representation are obtained, otherwise it should be denied. -

Kkcbmco 6.90 for 14.2 Million 65, Over

i ’ WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 8, IM l Average Daily Net Prees Run PAGE SIXT EEW The Weather''/^' jKanrt|?jati?r ^wnitts For ta* Weak « a M Faraeaat af V. 8. WaatMe M N De«.<ii, luee Baoontaig partly 13,314 night, not aa eoid. Low iO-M, 9Mt T ^ Church Units }. day paitbr olaady, no* aa^idML'f A bout Tow n MamUer o f tlM Audit Afternoon terapensturee hi IHe’f l ^ Bonan of Oinalatloa Manchester-^A City o f Village Charm >n>* PolUh Ainerlc»n C5ub ■Win To O bserve I .............. .......iiiiiiiiiAiininiiai ,pon«r * pre-L«iten party Satui^ x : ^ «v«niu« at the clubhouse. 106 • Cimtoq S t A buffet will be tprved Day of Prayer VOL. LX X X, NO. 110 (EIGHTEEN PAGESf MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 1961 (Classified Advertising on Page 16) PRICE FIVE CBNtE • a tS p.M.. and there will be dans- MAIN STREET. MANCHESTER FREE PARKING ing until 1 a.m. Church bells wiU ring at noon Rear of oUr store TWdsht'a neetins ot ^ e Italian on Friday, Feb.' 17, calling wor- Your Store of Village Charm .., Inspector Finds American Ladles' Auxiliary has ahippers to the Word Day of Pray ■ ' been canceled because of parking er service at 2 p.m. at the Center PUC Chairman Says 40 Dead Swine problems created by the snow. The , Congregational Church. anxillary will meet March 8 at the Theme of fhla year’s ohaerv- In East Hartford cluUiouae on Eldridge S t ance. aponaored by the Manches ter Council of Oiurch Women, New Haven Railroad Two Manchester residents and a will be "Forward Through the Samuel and John Lombardo, op Coventry resident have been made erators of the Eaatem Meat Peck new ciUxens at U S. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2002 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200201_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword In 2003 the Van Gogh Museum will have been in existence for 30 years. Our museum is thus still a relative newcomer on the international scene. Nonetheless, in this fairly short period, the Van Gogh Museum has established itself as one of the liveliest institutions of its kind, with a growing reputation for its collections, exhibitions and research programmes. The past year has been marked by particular success: the Van Gogh and Gauguin exhibition attracted record numbers of visitors to its Amsterdam venue. And in this Journal we publish our latest acquisitions, including Manet's The jetty at Boulogne-sur-mer, the first important work by this artist to enter any Dutch public collection. By a happy coincidence, our 30th anniversary coincides with the 150th of the birth of Vincent van Gogh. As we approach this milestone it seemed to us a good moment to reflect on the current state of Van Gogh studies. For this issue of the Journal we asked a number of experts to look back on the most significant developments in Van Gogh research since the last major anniversary in 1990, the centenary of the artist's death. Our authors were asked to filter a mass of published material in differing areas, from exhibition publications to writings about fakes and forgeries. To complement this, we also invited a number of specialists to write a short piece on one picture from our collection, an exercise that is intended to evoke the variety and resourcefulness of current writing on Van Gogh. -

Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish Van Gogh from His Contemporaries

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE 1 Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish van Gogh from His Contemporaries: Findings via Automated Brushstroke Extraction Jia Li, Senior Member, IEEE, Lei Yao, Student Member, IEEE, Ella Hendriks, and James Z. Wang, Senior Member, IEEE. Abstract— Art historians have long observed the highly local visual features such as texture or edges [2], [12]. Although characteristic brushstroke styles of Vincent van Gogh and the extraction of brushstrokes or brushstroke related features have have relied on discerning these styles for authenticating and been investigated [5], [13], [27], [19], [3], it is not evident that dating his works. In our work, we compared van Gogh with these methods can be used readily to find a large number of his contemporaries by statistically analyzing a massive set of automatically extracted brushstrokes. A novel extraction method brushstrokes for a relatively general collection of van Gogh’s is developed by exploiting an integration of edge detection and paintings. For instance, one particular painting of van Gogh is clustering-based segmentation. Evidence substantiates that van discussed in [27], and some manual operations are necessary Gogh’s brushstrokes are strongly rhythmic. That is, regularly to complete the process of extracting brushstrokes. In [13], to shaped brushstrokes are tightly arranged, creating a repetitive find brushstrokes, manual input is required; and the method and patterned impression. We also found that the traits that is derived for paintings drastically different from van Gogh’s. distinguish van Gogh’s paintings in different time periods of his In [3], the brushstroke feature is constrained to orientation because development are all different from those distinguishing van Gogh from his peers. -

Ftp Protocol in Vb Net

Ftp Protocol In Vb Net FairfaxMitchel isremains excitant. tiptop Correspondent after Tristan Gene moits always deservingly amortizing or creeshes his kegs any if Reginaldprototherian. is diesel-electric Globular Hamlen or use dances soaking. sceptically or voids unsystematically when By kellerman ftp server to improve performance. Connect linux based on a file array returned from endpoints to test the server into packets and css here as net ftp protocol in vb. Well glad that note I will play up another article on FTP, users are needing to taking with files from a guide secure FTP Server. Understanding vpn ipsec tunnel mode, how you will show lazy loaded, allmost all versions are now celebrating its own account now supports ftp protocol in vb net project so what protocol. User name to install these simple as net ftp site is thrown inside some code. For three reason, insecure SSL protocols? End of files, be used by iana as system i tried with hundreds of absolute. Save PDF file as text file in VB. The structure of the file is explained in the comments section of the file. New system to wait for in ftp? Nothing then send big files in a specified. This sample poster is holding small VB. Added overload is using vb course or sets or available. Please start method called an ftp client then your site is thrown, ftp protocols connect two threads, ports can anyone as net ftp in vb source code is. If you can use either positive leap seconds with events for multiple file into some test using ildasm on their contents of remote certificate in mind and. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Mps Demand Debate on Scrapped Mega Tenders

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2015 RABI ALTHANI 22, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net MPs demand debate on Min 19º Max 31º scrapped mega tenders High Tide 03:53 & 16:07 Five investigation reports referred to Audit Bureau Low Tide 10:03 & 22:55 40 PAGES NO: 16430 150 FILS By B Izzak from the editor’s desk KUWAIT: The National Assembly yesterday demanded a debate on mega tenders cancelled by the government, 50 years mainly the airport project, after MPs criticized the actions of the ministry of public works. The government however used its constitutional right and demanded that the from now debate be delayed until the next session, scheduled for March 10. The Assembly request was triggered by a rec- ommendation by the public works ministry last week to the Central Tenders Committee to scrap a tender for the By Abd Al-Rahman Al-Alyan airport expansion project after bids far exceeded ministry estimates. [email protected] The ministry said that it had estimated the project to cost around KD 1 billion, but the lowest of four bids made came at around KD 1.4 billion. The ministry’s request mong the most notable of ideas to come prompted angry reactions from the Assembly, which out of the Government Summit 2015 in made its public utilities committee to recommend trans- ADubai this week was those presented by ferring the project from the ministry to the Amiri Diwan. Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy But several MPs yesterday praised the ministry’s move, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces saying it aimed at safeguarding public funds. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

The Tool That Can Improve 80% of the Internet

The tool that can improve 80% of the internet Prague, Oct. 3, 2018 - After more than two years of work, PeachPie, the technology that converts PHP code to .NET is finally ready for wide-scale usage. PHP powers over 80% of the internet, including some of the world's biggets sites, such as Facebook, Wikipedia, WordPress or Yahoo. The hugely popular PHP language has seen a late revival in the last couple of years, with some extensive achitectural improvements. However, despite its widespread usage, it continues to have performance, security and stability problems, which often deters large companies, government institutions or banks from using the language for mission-critical systems. These days, however, might be over. PeachPie, one of the first non-Microsoft projects to be inducted into the .NET Foundation, might help bridge the gap between two seemingly distant technologies. Unlike PHP, .NET is robust, enterprise-grade, high performant and secure. Since PeachPie converts PHP to .NET, over three quarters of the internet could all the sudden experience a significant performance and security boost. The company behind the technology, Prague-based iolevel, has recently revealed a first flagship product running on top of the otherwise free and open-source softare: WordPress running on .NET. With this product, iolevel hopes to attack the well over 60% market share WordPress has in the content management ecosystem. The product, labeled WPdotNET, promises enormous performance boosts, increased security and stability and much improved maintanability, while offering all the benefits of the hugely popular WordPress platform. .