Art C.Rit1c1sm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literaturelk the DECADENTS

Literaturelk Around the World THE DECADENTS France. At the end of the 19th century a group of French poets, including Rimbaud, Verlaine and Mallarmé, formed a movement and called themselveb 'Les Décadents'. They aspired to set literature and art free from the materialistic preoccupations of industrialised society.They saw art as the highest expression of the human spirit, stating that art and life are strictly linked. These poets rejected the traditional values of society choosing instead an immoral and irregular lifestyle, free of any conventions or rules. England. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), the decadent, anti-conformist and dandy, who introduced himself to America with the famous phrase 'I have nothing to declare except my genius', is often linked to his French predecessors, however, he did not isolate V Gabriele D'Annunzio himself from the world, but instead craved popularity and fame. The epitome of the reading in his dandy is the protagonist of his novel The Picture of Dorían Gray (even if he is represented `Vittoriale degli italiani', the negatively). monumental citadel created by Italy. 'Decadentismo' is an Italian artistic movement influenced by the French and the Italian writer between 1921 and British Decadent Movement.Although differing in their approaches, like the other two 1938 in Gardone movements, it championed the irrational and the idiosyncratic against the advancing Riviera, on the tide of scientific rationalism and mass culture at the turn of the 20th century. Brescian Riverside of Lake Garda. Gabriele D'Annunzio (1863-1938) is generally considered the main representative of the Italian Decadentismo. He played a prominent role in Italian literature from 1889 to 1910 and after that in political life from 1914 to 1924. -

AMNH Digital Library

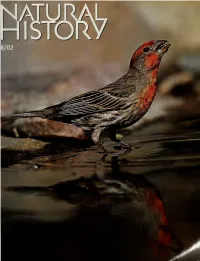

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Download Between the Lines 2017

the LINES Vanderbilt University, 2016–17 RESEARCH and from the LEARNING UNIVERSITY LIBRARIAN Places and Spaces International exhibit unites students, faculty and staff in celebrating mapping technology Dear colleagues and friends, ast spring, the Vanderbilt Heard Libraries hosted Places & Spaces: Mapping Science, It is my pleasure to share with you Between the Lines, a publication of an international exhibition the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries. In words, numbers and images, celebrating the use of data we offer a glimpse into the many ways our libraries support and enhance Lvisualizations to make sense of large MAPPING SCIENCE teaching, learning and research at Vanderbilt. Between the Lines will data streams in groundbreaking ways. introduce you to the remarkable things happening in the libraries and The campuswide exhibit proved to be perhaps even challenge your perception of the roles of libraries and intellectually enriching and socially unifying, according to campus leaders. librarians. We are grateful to the many donors and friends who made “The Places & Spaces: Mapping Science much of this work possible. exhibit brought together students, faculty and staff to celebrate technological The past academic year has been one of change for Vanderbilt’s Heard advances in data visualization that Libraries with new faces, new library services, new spaces and new facilitate our understanding of the world I programs. It has also been a year of continuity as we build collections, around us,” says Cynthia J. Cyrus, vice make resources accessible and provide contemplative and collaborative provost for learning and residential affairs. “From the disciplines of science and Ptolemy’s Cosmo- spaces for research and study. -

WRAP THESIS Robbins 1996.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36344 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Decadence and Sexual Politics in Three Fin-de-Siècle Writers: Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons and Vernon Lee Catherine Ruth Robbins Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick Department of English and Comparative Literature November, 1996 Contents Summary Introduction 1 Chapter One: Traditions of Nineteenth-Century Criticism 17 Chapter Two: Towards a Definition of Decadence 36 Chapter Three: 'Style, not sincerity': Wilde's Early Poems 69 Chapter Four: The Sphinx and The Ballad: Learning the Poetics of Restraint 105 Chapter Five: Arthur Symons — The Decadent Critic as Artist 137 Chapter Six: A Poetics of Decadence: Arthur Symons's bays and Nights and Silhouettes 165 Chapter Seven: 'Telling the Dancer from the Dance': Arthur Symon's London Nights 185 Chapter Eight: Vemon Lee: Decadent Woman? 211 Afterword: 'And upon this body we may press our lips' 240 Bibliography of Works Quoted and Consulted 244 List of Illustrations, bound between pages 136 and 137 Figure 1: 'The Sterner Sex', Punch, 26 November, 1891 Figure 2: 'Our Decadents', Punch, 7 July, 1894 Figure 3: 'Our Decadents', Punch, 27 October, 1894 Figure 4: Edward Bume-Jones, Pygmalion and the Image (1878), nos 1-3 Figure 5: Edward Bume-Jones, Pygmalion and the Image (1878), no. -

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis Zhi Gao1∗, Mo Shan2∗, Loong-Fah Cheong3, and Qingquan Li4,5 1 Interactive and Digital Media Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2 Temasek Laboratories, National University of Singapore 3 Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, National University of Singapore 4 The State Key Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping, and Remote Sensing, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China 5 Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Spatial Smart Sensing and Services, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China fgaozhinus, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Inspired by the outstanding performance of sparse coding in applications of image denoising, restoration, classification, etc, we pro- pose an adaptive sparse coding method for painting style analysis that is traditionally carried out by art connoisseurs and experts. Significantly improved over previous sparse coding methods, which heavily rely on the comparison of query paintings, our method is able to determine the au- thenticity of a single query painting based on estimated decision bound- ary. Firstly, discriminative patches containing the most representative characteristics of the given authentic samples are extracted via exploit- ing the statistical information of their representation on the DCT basis. Subsequently, the strategy of adaptive sparsity constraint which assigns higher sparsity weight to the patch with higher discriminative level is enforced to make the dictionary trained on such patches more exclu- sively adaptive to the authentic samples than via previous sparse coding algorithms. Relying on the learnt dictionary, the query painting can be authenticated if both better denoising performance and higher sparse representation are obtained, otherwise it should be denied. -

1 Introduction the Empire at the End of Decadence the Social, Scientific

1 Introduction The Empire at the End of Decadence The social, scientific and industrial revolutions of the later nineteenth century brought with them a ferment of new artistic visions. An emphasis on scientific determinism and the depiction of reality led to the aesthetic movement known as Naturalism, which allowed the human condition to be presented in detached, objective terms, often with a minimum of moral judgment. This in turn was counterbalanced by more metaphorical modes of expression such as Symbolism, Decadence, and Aestheticism, which flourished in both literature and the visual arts, and tended to exalt subjective individual experience at the expense of straightforward depictions of nature and reality. Dismay at the fast pace of social and technological innovation led many adherents of these less realistic movements to reject faith in the new beginnings proclaimed by the voices of progress, and instead focus in an almost perverse way on the imagery of degeneration, artificiality, and ruin. By the 1890s, the provocative, anti-traditionalist attitudes of those writers and artists who had come to be called Decadents, combined with their often bizarre personal habits, had inspired the name for an age that was fascinated by the contemplation of both sumptuousness and demise: the fin de siècle. These artistic and social visions of degeneration and death derived from a variety of inspirations. The pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), who had envisioned human existence as a miserable round of unsatisfied needs and desires that might only be alleviated by the contemplation of works of art or the annihilation of the self, contributed much to fin-de-siècle consciousness.1 Another significant influence may be found in the numerous writers and artists whose works served to link the themes and imagery of Romanticism 2 with those of Symbolism and the fin-de-siècle evocations of Decadence, such as William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Eugène Delacroix, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert. -

How Can Emotions Be Incorporated Meaningfully Into Design Practice?

The following are general comments about the structure and content of an academic essay written for university – they are not prescriptive and intended as an educational guide only. How can emotions be incorporated meaningfully into design practice? Introduction My research question is "How can emotions be incorporated meaningfully into design practice?" Comment [u1]: Your design question needs to be in your introduction. This was refined from my original question at the presentation stage of "How does emotion play a role in Comment [u2]: Some background to the reason you chose this question. It may shaping aesthetics?" I chose to specify the relationship between emotions and design practice as this gave a be necessary to define your key terms at this stage. greater focus to the practical opportunities for meaningful agency in the emotional domain of design. As Comment [u3]: Any particular elements in your question that are important my initial question indicated, the scope of my research is largely centred in the concerns of aesthetics visual communication. Comment [u4]: The student is indicating the scope of the question. For advice on writing an introduction, go to: Emotions are a relatively unacknowledged aspect of design practice; both formal education and design http://www.uts.edu.au/currentstudents/su pport/helps/self-helpresources/academic- writing/essay-writing literature tend to align with modernist ideals of rationalism and scientific objectivity. Additionally, the Comment [u5]: This paragraph is domain of aesthetics tends to be considered mere "decoration" or "prettying up". This research intends largely about why your question is important - its relevance and significance. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Decadent

DECADENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Shayla Black | 341 pages | 22 Jul 2011 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780425217214 | English | New York, United States Decadent PDF Book Finally, the third period, which can be seen as a postlude to Decadentism, is marked by the voices of Italo Svevo , Luigi Pirandello and the Crepusculars. Dictionary Entries near decadent decade-long decadence decadency decadent decadentism decades-long decadic See More Nearby Entries. Manchester University Press ND. Schools of poetry. Ortega y Gasset: an outline of his philosophy. Decadence, on the other hand, sees no path to higher truth in words and images. In Italian art and literature critic Mario Praz completed a broad study of morbid and erotic literature, translated and published in English as The Romantic Agony Translated by Bradford Cook. Did you know He has been lauded to his dedication to this cause throughout his career, but it has been suggested that, while he lived as a decadent and heralded their work, his own work was more frustrated, hopeless, and empty of the pleasure that had attracted him to the movement in the first place. Do You Know This Word? From the Decadent movement he learned the basic idea of a dandy , and his work is almost entirely focused on developing a philosophy in which the Dandy is the consummate human, surrounded by riches and elegance, theoretically above society, just as doomed to death and despair as they. Similar to Lenin's use of it, left communists, coming from the Communist International themselves started in fact with a theory of decadence in the first place, yet the communist left sees the theory of decadence at the heart of Marx's method as well, expressed in famous works such as The Communist Manifesto , Grundrisse , Das Kapital but most significantly in Preface to the Critique of Political Economy. -

How Can Emotions Be Incorporated Meaningfully Into Design Practice?

The following are general comments about the structure and content of an academic essay written for university – they are not prescriptive and intended as an educational guide only. How can emotions be incorporated meaningfully into design practice? Introduction My research question is "How can emotions be incorporated meaningfully into design practice?" Commented [u1]: Your design question needs to be in your introduction. This was refined from my original question at the presentation stage of "How does emotion play a role in Commented [u2]: Some background to the reason you chose this question. It may be necessary to define your key terms at this shaping aesthetics?" I chose to specify the relationship between emotions and design practice as this gave a stage. Commented [u3]: Any particular elements in your question that greater focus to the practical opportunities for meaningful agency in the emotional domain of design. As are important my initial question indicated, the scope of my research is largely centred in the concerns of aesthetics visual communication. Commented [u4]: The student is indicating the scope of the question. For advice on writing an introduction, go to: http://www.uts.edu.au/currentstudents/support/helps/self- Emotions are a relatively unacknowledged aspect of design practice; both formal education and design helpresources/academic-writing/essay-writing literature tend to align with modernist ideals of rationalism and scientific objectivity. Additionally, the Commented [u5]: This paragraph is largely about why your question is important - its relevance and significance. Here, the domain of aesthetics tends to be considered mere "decoration" or "prettying up". This research intends student is identifying it as a gap in the literature. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2002 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200201_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword In 2003 the Van Gogh Museum will have been in existence for 30 years. Our museum is thus still a relative newcomer on the international scene. Nonetheless, in this fairly short period, the Van Gogh Museum has established itself as one of the liveliest institutions of its kind, with a growing reputation for its collections, exhibitions and research programmes. The past year has been marked by particular success: the Van Gogh and Gauguin exhibition attracted record numbers of visitors to its Amsterdam venue. And in this Journal we publish our latest acquisitions, including Manet's The jetty at Boulogne-sur-mer, the first important work by this artist to enter any Dutch public collection. By a happy coincidence, our 30th anniversary coincides with the 150th of the birth of Vincent van Gogh. As we approach this milestone it seemed to us a good moment to reflect on the current state of Van Gogh studies. For this issue of the Journal we asked a number of experts to look back on the most significant developments in Van Gogh research since the last major anniversary in 1990, the centenary of the artist's death. Our authors were asked to filter a mass of published material in differing areas, from exhibition publications to writings about fakes and forgeries. To complement this, we also invited a number of specialists to write a short piece on one picture from our collection, an exercise that is intended to evoke the variety and resourcefulness of current writing on Van Gogh. -

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL of DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks ISSN: 2515-0073 Date of Acceptance: 1 June 2018 Date of Publication: 21 June 2018 Citation: Rita Dirks, ‘Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 1 (2018), 35-55. volupte.gold.ac.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks Ambrose University Canada has never produced a major man of letters whose work gave a violent shock to the sensibilities of Puritans. There was some worry about Carman, who had certain qualities of the fin de siècle poet, but how mildly he expressed his queer longings! (E. K. Brown) Decadence came to Canada softly, almost imperceptibly, in the 1880s, when the Confederation poet Bliss Carman published his first poems and met the English chronicler and leading poet of Decadence, Arthur Symons. The event of Decadence has gone largely unnoticed in Canada; there is no equivalent to David Weir’s Decadent Culture in the United States: Art and Literature Against the American Grain (2008), as perhaps has been the fate of Decadence elsewhere. As a literary movement it has been, until a recent slew of publications on British Decadence, relegated to a transitional or threshold period. As Jason David Hall and Alex Murray write: ‘It is common practice to read [...] decadence as an interstitial moment in literary history, the initial “falling away” from high Victorian literary values and forms before the bona fide novelty of modernism asserted itself’.1 This article is, in part, an attempt to bring Canadian Decadence into focus out of its liminal state/space, and to establish Bliss Carman as the representative Canadian Decadent. -

Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish Van Gogh from His Contemporaries

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE 1 Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish van Gogh from His Contemporaries: Findings via Automated Brushstroke Extraction Jia Li, Senior Member, IEEE, Lei Yao, Student Member, IEEE, Ella Hendriks, and James Z. Wang, Senior Member, IEEE. Abstract— Art historians have long observed the highly local visual features such as texture or edges [2], [12]. Although characteristic brushstroke styles of Vincent van Gogh and the extraction of brushstrokes or brushstroke related features have have relied on discerning these styles for authenticating and been investigated [5], [13], [27], [19], [3], it is not evident that dating his works. In our work, we compared van Gogh with these methods can be used readily to find a large number of his contemporaries by statistically analyzing a massive set of automatically extracted brushstrokes. A novel extraction method brushstrokes for a relatively general collection of van Gogh’s is developed by exploiting an integration of edge detection and paintings. For instance, one particular painting of van Gogh is clustering-based segmentation. Evidence substantiates that van discussed in [27], and some manual operations are necessary Gogh’s brushstrokes are strongly rhythmic. That is, regularly to complete the process of extracting brushstrokes. In [13], to shaped brushstrokes are tightly arranged, creating a repetitive find brushstrokes, manual input is required; and the method and patterned impression. We also found that the traits that is derived for paintings drastically different from van Gogh’s. distinguish van Gogh’s paintings in different time periods of his In [3], the brushstroke feature is constrained to orientation because development are all different from those distinguishing van Gogh from his peers.