Franz Marc As an Ethologist by Jean Carey a Thesis Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMNH Digital Library

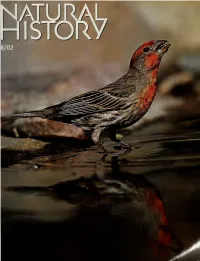

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Final Report Provenance Research

Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation Final Report Project management Dr. Thorsten Sadowsky, Director Annick Haldemann, Registrar [email protected] Project handling and report Julia Sophie Syperreck MA, Research Assistant [email protected] 31 August 2018 Kirchner Museum Davos Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 2 Contents 3 I. Work report 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project 5 b. Work performed by the project staff and project schedule 6 c. Methodical approach and manner of publication of the findings 7 d. Object statistics 9 e. List of the historical agents (individuals and institutions) relevant to the project 10 f. Documentation of the findings for third parties 11 II. Summary 12 a. Evaluation of the findings 12 b. Unresolved issues and need for further research 13 III. Appendix: List of works Kirchner Museum Davos I. Work report Provenance Research on the Baumgart-Möller Donation 4 a. The situation and state of research at the beginning of the project At the beginning of the project an assessment was made which groups of works within the collection are more likely to be linked to the “liquidation” of private and public collections during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany in the years from 1933 to 1945. It was found that there is only very patchy provenance information for the forty-two artworks donated in 2000 to the Kirchner Museum Davos by “Rosemarie and Konrad Baumgart-Möller in memory of Ferdinand Möller, Berlin.” Since “Möller” is one of the red-flag names in provenance research, the investigation of this part of the collection was given priority. -

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis

Adaptive Sparse Coding for Painting Style Analysis Zhi Gao1∗, Mo Shan2∗, Loong-Fah Cheong3, and Qingquan Li4,5 1 Interactive and Digital Media Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2 Temasek Laboratories, National University of Singapore 3 Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, National University of Singapore 4 The State Key Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping, and Remote Sensing, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China 5 Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Spatial Smart Sensing and Services, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China fgaozhinus, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Inspired by the outstanding performance of sparse coding in applications of image denoising, restoration, classification, etc, we pro- pose an adaptive sparse coding method for painting style analysis that is traditionally carried out by art connoisseurs and experts. Significantly improved over previous sparse coding methods, which heavily rely on the comparison of query paintings, our method is able to determine the au- thenticity of a single query painting based on estimated decision bound- ary. Firstly, discriminative patches containing the most representative characteristics of the given authentic samples are extracted via exploit- ing the statistical information of their representation on the DCT basis. Subsequently, the strategy of adaptive sparsity constraint which assigns higher sparsity weight to the patch with higher discriminative level is enforced to make the dictionary trained on such patches more exclu- sively adaptive to the authentic samples than via previous sparse coding algorithms. Relying on the learnt dictionary, the query painting can be authenticated if both better denoising performance and higher sparse representation are obtained, otherwise it should be denied. -

Franz Marc Animals Fine Art Pages

Playing Weasels Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1909 Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Franz Marc was a German painter and printmaker that lived from 1880 to 1916. He studied in Munich and in France. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Siberian Sheepdogs Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1910 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Post-Impressionism Interesting Fact: While serving in the German military in World War I, Marc painted tarp covers in various artistic styles, ranging “from Manet to Kandinsky” in hopes of hiding artillery. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Blue Horse I Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Deer in the Snow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Donkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Most of Marc’s work portrays animals in a very stark way, using bold colors. His style caught the attention of the art world. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Monkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Interesting Fact: A “frieze” is a wide horizontal painting or other decoration, often displayed on a wall near the ceiling. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Resting Cows Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com The Yellow Cow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: The style of Expressionism was a modern form of art that began in the early 1900s. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2002 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200201_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword In 2003 the Van Gogh Museum will have been in existence for 30 years. Our museum is thus still a relative newcomer on the international scene. Nonetheless, in this fairly short period, the Van Gogh Museum has established itself as one of the liveliest institutions of its kind, with a growing reputation for its collections, exhibitions and research programmes. The past year has been marked by particular success: the Van Gogh and Gauguin exhibition attracted record numbers of visitors to its Amsterdam venue. And in this Journal we publish our latest acquisitions, including Manet's The jetty at Boulogne-sur-mer, the first important work by this artist to enter any Dutch public collection. By a happy coincidence, our 30th anniversary coincides with the 150th of the birth of Vincent van Gogh. As we approach this milestone it seemed to us a good moment to reflect on the current state of Van Gogh studies. For this issue of the Journal we asked a number of experts to look back on the most significant developments in Van Gogh research since the last major anniversary in 1990, the centenary of the artist's death. Our authors were asked to filter a mass of published material in differing areas, from exhibition publications to writings about fakes and forgeries. To complement this, we also invited a number of specialists to write a short piece on one picture from our collection, an exercise that is intended to evoke the variety and resourcefulness of current writing on Van Gogh. -

Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish Van Gogh from His Contemporaries

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE 1 Rhythmic Brushstrokes Distinguish van Gogh from His Contemporaries: Findings via Automated Brushstroke Extraction Jia Li, Senior Member, IEEE, Lei Yao, Student Member, IEEE, Ella Hendriks, and James Z. Wang, Senior Member, IEEE. Abstract— Art historians have long observed the highly local visual features such as texture or edges [2], [12]. Although characteristic brushstroke styles of Vincent van Gogh and the extraction of brushstrokes or brushstroke related features have have relied on discerning these styles for authenticating and been investigated [5], [13], [27], [19], [3], it is not evident that dating his works. In our work, we compared van Gogh with these methods can be used readily to find a large number of his contemporaries by statistically analyzing a massive set of automatically extracted brushstrokes. A novel extraction method brushstrokes for a relatively general collection of van Gogh’s is developed by exploiting an integration of edge detection and paintings. For instance, one particular painting of van Gogh is clustering-based segmentation. Evidence substantiates that van discussed in [27], and some manual operations are necessary Gogh’s brushstrokes are strongly rhythmic. That is, regularly to complete the process of extracting brushstrokes. In [13], to shaped brushstrokes are tightly arranged, creating a repetitive find brushstrokes, manual input is required; and the method and patterned impression. We also found that the traits that is derived for paintings drastically different from van Gogh’s. distinguish van Gogh’s paintings in different time periods of his In [3], the brushstroke feature is constrained to orientation because development are all different from those distinguishing van Gogh from his peers. -

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt. -

The Blue Rider

THE BLUE RIDER 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 1 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 2 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 2 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 HELMUT FRIEDEL ANNEGRET HOBERG THE BLUE RIDER IN THE LENBACHHAUS, MUNICH PRESTEL Munich London New York 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 3 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 4 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 CONTENTS Preface 7 Helmut Friedel 10 How the Blue Rider Came to the Lenbachhaus Annegret Hoberg 21 The Blue Rider – History and Ideas Plates 75 with commentaries by Annegret Hoberg WASSILY KANDINSKY (1–39) 76 FRANZ MARC (40 – 58) 156 GABRIELE MÜNTER (59–74) 196 AUGUST MACKE (75 – 88) 230 ROBERT DELAUNAY (89 – 90) 260 HEINRICH CAMPENDONK (91–92) 266 ALEXEI JAWLENSKY (93 –106) 272 MARIANNE VON WEREFKIN (107–109) 302 ALBERT BLOCH (110) 310 VLADIMIR BURLIUK (111) 314 ADRIAAN KORTEWEG (112 –113) 318 ALFRED KUBIN (114 –118) 324 PAUL KLEE (119 –132) 336 Bibliography 368 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 5 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 6 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 PREFACE 7 The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), the artists’ group formed by such important fi gures as Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Alexei Jawlensky, and Paul Klee, had a momentous and far-reaching impact on the art of the twentieth century not only in the art city Munich, but internationally as well. Their very particular kind of intensely colorful, expressive paint- ing, using a dense formal idiom that was moving toward abstraction, was based on a unique spiritual approach that opened up completely new possibilities for expression, ranging in style from a height- ened realism to abstraction. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Katie Ziglar Deb Spears (202) 842-6353 ** Press preview: Wednesday, November 15, 1989 EXPRESSIONIST AND OTHER MODERN GERMAN PAINTINGS AT NATIONAL GAT.T.KRY Washington, D.C., September 18, 1989 Thirty-four outstanding German paintings from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection begin an American tour at the National Gallery of Art, November 19, 1989 through January 14, 1990. Expressionism and Modern German Painting from the Thyssen- Bornemisza Collection contains important examples by artists whose major paintings are extremely rare in this country. The nineteen artists represented in the show include Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Otto Dix, Johannes Itten, Franz Marc, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The intense and colorful works in this exhibition are among the modern paintings Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza has added, along with old master paintings, to the collection he inherited from his father> Baron Heinrich (1875-1947). Expressionism and Modern German Painting, to be seen at three American museums, is selected from the large collection on view at the Baron's home, Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland, through October 29, 1989. It is the first exhibition devoted entirely to the modern German paintings in the collection. -more- expressionism and modern german painting . page two "Comprehensive groupings of expressionism and modern German paintings are extremely rare in American museums and we are pleased to offer a show of this extraordinary caliber here this fall," said J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery. The American show has been selected by Andrew Robison, senior curator at the National Gallery. -

13 Galley-CORRECTIONS.Wps

1 Ginosko Literary Journal, #13 Summer 2013 PO Box 246 Fairfax, CA 94978 Robert Paul Cesaretti, Editor GinoskoLiteraryJournal.com est 2002 Writers retain copyrights Cover art: Delisa Sage “Sacred Geometry” Mixed media collage San Rafael Ca. delisasage.com 2 ginosko A word meaning to perceive, understand, realize, come to know; knowledge that has an inception, a progress, an attainment. The recognition of truth from experience. 3 CCC OOO NNN TTT EEE NNN TTT SSS Another Kind of Secret 10 The Night-Blooming Cactus 11 The Fire 12 Michael Hettich RITUAL 14 BONE LANGUAGE 15 UNDER THE FULL MOON 16 DOVES FLY IN MY HEART 17 Marie Olofsdotter WHEN MOTHER FLEW KITES 18 Stephen Poleskie A Drowning 22 Making Taralli 23 Vanessa Young Promising Nothing 25 Ian Sherman PROPORTIONATE WISHES 27 SKIN DEEP 27 TERRIBLY WE LAUGH 28 Diane Webster Mountains 29 Joe Sullivan A WOMAN PHOTOGRAPHING A RIVER 30 NIGHT RECONNAISSANCE 31 David Wagoner ETYMOLOGY 32 Edward Butscher Water Marks 33 Margaret Elysia Garcia THE GIRL IN THE CLOSET 35 Ed Thompson 4 Concession 38 Gale Acuff It Makes Your Ears Ring 40 Seller’s Market 40 Kirby Wright IN MY HEAD 41 THE CLOCK 41 THE TURN 42 WATCHING 42 J.R. Solonche The House Next Door 43 To End it All 47 Thomas Sanfilip Lesson 49 Mojácar 50 #5 Bus 51 Body Remembers 52 Black Bass Inn 53 Art of Fire 54 Clougmore to Minaun 56 Dubliner 57 Staying the Same 58 Madeleine Beckman UNDER THE MINISCUS 59 Sam Frankl Pulmonary 60 Full Moon Fever 61 July 3rd 1971 62 Kory Ferbet Paradox 63 Hush 63 Retrospective 64 Phebe Davidson 5 eau de vie 65 -

< Paul Cézanne >

Still Life: Plate of Peaches, 1879-80. Oil on canvas, 59.7 x 73.3 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser 78.2514.4 < PAUL CÉZANNE > Paul Cézanne’s (b. 1839, Aix-en-Provence, France; d. 1906, Aix-en-Provence) complex still lifes are an important part of his quest for empirical truth in painting. Because these THE GREAT U inanimate objects did not move, like human “I will astonish Paris with an apple,” he subjects might, during the painting sessions, once said.3 and they were available any time of day or PAUL CÉZANNE night, they were an ideal subject for a slow- Cézanne set up his still lifes with great care. working, analytical artist like Cézanne. A testimony by an acquaintance describes his Sometimes the fruit or flowers he used method of preparing a still life: “No sooner P HEAVAL would wither and die before the painting was the cloth draped on the table with innate was completed and would need to be taste than Cézanne set out the peaches in replaced by paper flowers and artificial fruit. such a way as to make the complementary colors vibrate, grays next to reds, yellows to His work was motivated by a desire to give blues, leaning, tilting, balancing the fruit at the sculptural weight and volume to everyday angles he wanted, sometimes pushing a one- objects. In Cézanne’s still lifes ambiguities sous or two-sous piece [French coins] under abound. As if by magic, the tablecloth we them. You could see from the care he took see in Still Life: Plate of Peaches is able to how much it delighted his eye.”4 But when levitate several pieces of fruit without any he began to paint, the picture might change visible means of support. -

Wassily Kandinsky Papers, 1911-1940 (Bulk 1921-1937)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1r29n4zp Online items available Finding aid for the Wassily Kandinsky papers, 1911-1940 (bulk 1921-1937) Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Wassily Kandinsky 850910 1 papers, 1911-1940 (bulk 1921-1937) Descriptive Summary Title: Wassily Kandinsky papers Date (inclusive): 1911-1940 (bulk 1921-1937) Number: 850910 Creator/Collector: Kandinsky, Wassily Physical Description: 2 Linear Feet(3 boxes, 1 flat file folder) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Russian-born artist considered to be one of the creators of abstract painting. Papers document Kandinsky's teachings at the Bauhaus, his writings, his involvement with the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences (RAKhN) in Moscow, and his professional contacts with art dealers, artists, collectors, and publishers. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German and Russian with some English and French. Biographical / Historical Note Wasily Kandinsky [Vasilii Vasil'evich Kandinskii] was born in 1866 in Moscow, Russia and died in 1944 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. He is considered one of the first creators of purely abstract painting. In 1896, after academic studies and initial career in law and social sciences, Kandinsky turned down an offer of professorship in jurisprudence, and together with his first wife Anja Shemiakina, left Russia for Munich with the intention of becoming a painter.