Introduction of Foreign Pollinators, Prospects and Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Maryland Entomologist

THE MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST Insect and related-arthropod studies in the Mid-Atlantic region Volume 7, Number 2 September 2018 September 2018 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 7, Number 2 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.mdentsoc.org Executive Committee: President Frederick Paras Vice President Philip J. Kean Secretary Janet A. Lydon Treasurer Edgar A. Cohen, Jr. Historian (vacant) Journal Editor Eugene J. Scarpulla E-newsletter Editors Aditi Dubey The Maryland Entomological Society (MES) was founded in November 1971, to promote the science of entomology in all its sub-disciplines; to provide a common meeting venue for professional and amateur entomologists residing in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and nearby areas; to issue a periodical and other publications dealing with entomology; and to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information through its meetings and publications. The MES was incorporated in April 1982 and is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, scientific organization. The MES logo features an illustration of Euphydryas phaëton (Drury) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), the Baltimore Checkerspot, with its generic name above and its specific epithet below (both in capital letters), all on a pale green field; all these are within a yellow ring double-bordered by red, bearing the message “● Maryland Entomological Society ● 1971 ●”. All of this is positioned above the Shield of the State of Maryland. In 1973, the Baltimore Checkerspot was named the official insect of the State of Maryland through the efforts of many MES members. Membership in the MES is open to all persons interested in the study of entomology. All members receive the annual journal, The Maryland Entomologist, and the monthly e-newsletter, Phaëton. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8z91q49s Author Ward, Laura True Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program By Laura T Ward A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nicholas J. Mills, Chair Professor Erica Bree Rosenblum Professor Eileen A. Lacey Fall 2020 Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program © 2020 by Laura T Ward Abstract Bees and belonging: Pesticide detection for wild bees in California agriculture and sense of belonging for undergraduates in a mentorship program By Laura T Ward Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Nicholas J. Mills, Chair This dissertation combines two disparate subjects: bees and belonging. The first two chapters explore pesticide exposure for wild bees and honey bees visiting crop and non-crop plants in northern California agriculture. The final chapter utilizes surveys from a mentorship program as a case study to analyze sense of belonging among undergraduates. The first chapter of this dissertation explores pesticide exposure for wild bees and honey bees visiting sunflower crops. -

Irrigation Method Does Not Affect Wild Bee Pollinators of Hybrid Sunflower by Hillary Sardiñas, Collette Yee and Claire Kremen

Research Article Irrigation method does not affect wild bee pollinators of hybrid sunflower by Hillary Sardiñas, Collette Yee and Claire Kremen Irrigation method has the potential to directly or indirectly influence populations of factors that determine crop success, such wild bee crop pollinators nesting and foraging in irrigated crop fields. The majority of as pollination. Wild bees are the most effective and wild bee species nest in the ground, and their nests may be susceptible to flooding. In abundant crop pollinators (Garibaldi addition, their pollination of crops can be influenced by nectar quality and quantity, et al. 2013). The majority of wild bees which are related to water availability. To determine whether different irrigation excavate nests beneath the soil (known methods affect crop pollinators, we compared the number of ground-nesting bees as ground nesters). Irrigation has the po- tential to saturate nests, possibly drown- nesting and foraging in drip- and furrow-irrigated hybrid sunflower fields in the ing bee larvae and adults. It could also Sacramento Valley. We found that irrigation method did not impact wild bee nesting indirectly impact crop pollinators by rates or foraging bee abundance or bee species richness. These findings suggest that affecting their foraging choices. Bee for- changing from furrow irrigation to drip irrigation to conserve water likely will not alter aging decisions are often related to floral reward, namely nectar quantity and hybrid sunflower crop pollination. quality (Roubik and Buchmann 1984; Stone 1994). Nectar production is related to water availability; increased water rrigation practices and water use ef- 1969, delivers water directly to the plant leads to higher nectar volume expressed ficiency are increasingly scrutinized root zone, thus improving water effi- (e.g., Petanidou et al. -

Wild Bee Declines and Changes in Plant-Pollinator Networks Over 125 Years Revealed Through Museum Collections

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2018 WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS Minna Mathiasson University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Mathiasson, Minna, "WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS" (2018). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1192. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILD BEE DECLINES AND CHANGES IN PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS OVER 125 YEARS REVEALED THROUGH MUSEUM COLLECTIONS BY MINNA ELIZABETH MATHIASSON BS Botany, University of Maine, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology May, 2018 This thesis has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences: Integrative and Organismal Biology by: Dr. Sandra M. Rehan, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Carrie Hall, Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Janet Sullivan, Adjunct Associate Professor of Biology On April 18, 2018 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Programs Open-File Report 2020–1037 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey A B C D E F G H I Cover. A, Bumble bee (Bombus sp.) visiting a locowood flower. Photograph by Stacy Simanonok, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). B, Honey bee (Apis mellifera) foraging on yellow sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis). Photograph by Sarah Scott, USGS. C, Two researchers working on honey bee colonies in a North Dakota apiary. Photograph by Elyssa McCulloch, USGS. D, Purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea) against a backdrop of grass. Photograph by Stacy Simanonok, USGS. E, Conservation Reserve Program pollinator habitat in bloom. Photograph by Clint Otto, USGS. F, Prairie onion (Allium stellatum) along the slope of a North Dakota hillside. Photograph by Mary Powley, USGS. G, A researcher assesses a honey bee colony in North Dakota. Photograph by Katie Lee, University of Minnesota. H, Honey bee foraging on alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Photograph by Savannah Adams, USGS. I, Bee resting on woolly paperflower (Psilostrophe tagetina). Photograph by Angela Begosh, Oklahoma State University. Front cover background and back cover, A USGS research transect on a North Dakota Conservation Reserve Program field in full bloom. Photograph by Mary Powley, USGS. Forage and Habitat for Pollinators in the Northern Great Plains—Implications for U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Programs By Clint R.V. Otto, Autumn Smart, Robert S. Cornman, Michael Simanonok, and Deborah D. Iwanowicz Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. -

FORTY YEARS of CHANGE in SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES Catherine Cumberland University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 7-15-2019 FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES Catherine Cumberland University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cumberland, Catherine. "FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/321 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catherine Cumberland Candidate Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Kenneth Whitney, Ph.D., Chairperson Scott Collins, Ph.D. Paula Klientjes-Neff, Ph.D. Diane Marshall, Ph.D. Kelly Miller, Ph.D. i FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES by CATHERINE CUMBERLAND B.A., Biology, Sonoma State University 2005 B.A., Environmental Studies, Sonoma State University 2005 M.S., Ecology, Colorado State University 2014 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy BIOLOGY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2019 ii FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES by CATHERINE CUMBERLAND B.A., Biology B.A., Environmental Studies M.S., Ecology Ph.D., Biology ABSTRACT Changes in a regional bee assemblage were investigated by repeating a 1970s study from the U.S. -

EFFECTS of LAND USE on NATIVE BEE DIVERSITY Byron

THE BEES OF THE AMERICAN AND COSUMNES RIVERS IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA: EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON NATIVE BEE DIVERSITY Byron Love B.S., California State University, Humboldt, 2003 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES (Biological Conservation) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SUMMER 2010 © 2010 Byron Love ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE BEES OF THE AMERICAN AND COSUMNES RIVERS IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA: EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON NATIVE BEE DIVERSITY A Thesis by Byron Love Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Shannon Datwyler __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Patrick Foley __________________________________, Third Reader Dr. Jamie Kneitel __________________________________, Fourth Reader Dr. James W. Baxter Date:____________________ iii Student: Byron Love I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. ______________________,Graduate Coordinator _________________ Dr. James W. Baxter Date Department of Biological Sciences iv Abstract of THE BEES OF THE AMERICAN AND COSUMNES RIVERS IN SACRAMENTO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA: EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON NATIVE BEE DIVERSITY by Byron Love A survey of the bees in semi-natural habitat along the American and Cosumnes rivers in Sacramento County, California, was conducted during the flower season of 2007. Although the highly modified landscapes surrounding the two rivers is distinctly different, with urban and suburban development dominant along the American River, and agriculture along the Cosumnes River, there is no difference in the proportion of modified landscape between the two rivers. -

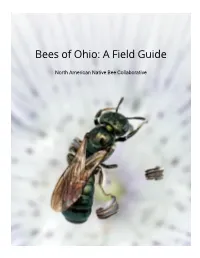

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

Changes in the Summer Wild Bee Community Following a Bark Beetle Outbreak in a Douglas-Fir Forest

Environmental Entomology, XX(XX), 2020, 1–12 doi: 10.1093/ee/nvaa119 Pollinator Ecology and Management Research Changes in the Summer Wild Bee Community Following a Bark Beetle Outbreak in a Douglas-fir Forest Gabriel G. Foote,1,6,7 Nathaniel E. Foote,2 Justin B. Runyon,3 Darrell W. Ross,1,4 and Christopher J. Fettig5 1Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, 2Forest and Rangeland Stewardship, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, 3Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1648 South 7th Street, Bozeman, MT 59717, 4Present address: Department of Entomology, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58108, 5Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 1731 Research Park Drive, Davis, CA 95618, 6Present address: Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616, and 7Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Subject Editor: Theresa Pitts-Singer Received 23 March 2020; Editorial decision 28 August 2020 Abstract AADate The status of wild bees has received increased interest following recent estimates of large-scale declines in their abundances across the United States. However, basic information is limited regarding the factors affecting wild bee communities in temperate coniferous forest ecosystems. To assess the early responses of bees to bark beetle AAMonth disturbance, we sampled the bee community of a Douglas-fir,Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.), forest in western Idaho, United States during a Douglas-fir beetle,Dendroctonus pseudotsugae Hopkins (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), AAYear outbreak beginning in summer 2016. We resampled the area in summer 2018 following reductions in forest canopy cover resulting from mortality of dominant and codominant Douglas-fir. -

The Best Wildflowers for Wild Bees

Journal of Insect Conservation (2019) 23:819–830 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-019-00180-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The best wildfowers for wild bees Rachel N. Nichols1 · Dave Goulson1 · John M. Holland2 Received: 31 January 2019 / Accepted: 23 September 2019 / Published online: 28 September 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Governmental agri-environment schemes (AES) aim to improve pollinator abundance and diversity on farmland by sowing wildfower seed mixes. These often contain high proportions of Fabaceae, particularly Trifolium (clovers), which are attrac- tive to some bumblebee species, but not to most of the ~ 240 solitary bee species in the UK. Here we identify wildfowers that are attractive to a greater range of wild bee species. Forty-fve wildfower species being farmed for commercial seed production on a single farm were surveyed for native bees. Bee walks were conducted through discrete wildfower areas from April until August in 2018. The results indicate that including a range of Apiaceae, Asteraceae, and Geraniaceae in seed mixes would cater for a wide diversity of bee species. A total of 14 wildfower species across nine families attracted 37 out of the 40 bee species recorded on the farm, and accounted for 99.7% of all visitations. Only two of these 14 species are included in current AES pollinator mixes. Unexpectedly, few visits were made by bumblebees to Trifolium spp. (0.5%), despite their being considered an important food source for bumblebees, while Anthyllis vulneraria and Geranium pratense were highly attractive. For solitary bees, Crepis capillaris, Sinapsis arvensis, Convolvulus arvensis and Chaerophyllum temulum were amongst the best performing species, none of which are usually included in sown fower mixes. -

Community Patterns and Plant Attractiveness to Pollinators in the Texas High Plains

Scale-Dependent Bee (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) Community Patterns and Plant Attractiveness to Pollinators in the Texas High Plains by Samuel Discua, B.Sc., M.Sc. A Dissertation In Plant and Soil Science Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Scott Longing Chair of the Committee Nancy McIntyre Robin Verble Cynthia McKenney Joseph Young Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Samuel Discua Texas Tech University, Samuel Discua, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many who helped me along the way on this long and difficult journey. I want to take a moment to thank them. First, I wish to thank my dissertation committee. Without their guidance, I would not have made it. Dr. McIntytre, Dr. McKenney, Dr. Young and Dr. Verble served as wise committee members, and Dr. Longing, my committee chair, for sticking with me and helping me reach my goal. To the Longing Lab members, Roberto Miranda, Wilber Gutierrez, Torie Wisenant, Shelby Chandler, Bryan Guevara, Bianca Rendon, Christopher Jewett, thank you for all the hard work. To my family, my parents, my sisters, and Balentina and Bruno: you put up with me being distracted and missing many events. Finally, and most important, to my wife, Baleshka, your love and understanding helped me through the most difficult times. Without you believing in me, I never would have made it. It is time to celebrate; you earned this degree right along with me. I am forever grateful for your patience and understanding. -

The Best Wildflowers for Wild Bees

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online The best wildflowers for wild bees Article (Published Version) Nichols, Rachel N, Goulson, Dave and Holland, John M (2019) The best wildflowers for wild bees. Journal of Insect Conservation. ISSN 1366-638X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/86615/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Journal of Insect Conservation https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-019-00180-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The best wildfowers for wild bees Rachel N.