Tanzania Draft 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE SEMBCORP PROPOSES VOLUNTARY TENDER OFFER TO ACQUIRE SHARES IN CASCAL, A LEADING PROVIDER OF WATER AND WASTEWATER SERVICES - Irrevocable undertaking by majority shareholder, Biwater to tender its 58.4% shareholding - Offer price of US$6.75 per share, if at least 80% of the outstanding common shares have been validly tendered and not withdrawn or US$6.40 per share, if at least 17,868,543, but less than 80% of the outstanding common shares have been validly tendered and not withdrawn - Major milestone for Sembcorp in the fast-growing water sector SINGAPORE, April 26, 2010 – Sembcorp Industries Ltd (Sembcorp) today announces that its wholly owned subsidiary, Sembcorp Utilities Pte Ltd (Sembcorp Utilities) has entered into a tender offer and stockholder support agreement with Biwater Investments Limited (Biwater), to acquire Biwater’s 17,868,543 shares of Cascal N.V. (Cascal) (representing approximately 58.4% of the outstanding common shares of Cascal), a New York Stock Exchange-listed company and leading provider of water and wastewater services, and to launch a tender offer to acquire all of the outstanding common shares of Cascal. Tang Kin Fei, Group President & CEO of Sembcorp Industries said, “This acquisition will transform Sembcorp into a global water service provider and provide the platform for the Group to accelerate our growth in the future. We will have water and wastewater facilities in 31 operating locations in 11 countries around the world, and our water capacity in operation and 1 under development globally will increase by 50% from four million to close to six million cubic metres per day. -

International Investment Agreements (Iias): Frequently Asked Questions

International Investment Agreements (IIAs): Frequently Asked Questions Updated May 15, 2015 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44015 International Investment Agreements (IIAs): Frequently Asked Questions Summary In recent decades, the United States has entered into binding investment agreements with foreign countries to facilitate investment flows, reduce restrictions on foreign investment and expand market access, and enhance investor protections, while balancing other policy interests. Some World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements address investment issues in a limited manner. In the absence of a comprehensive multilateral agreement, bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and investment chapters in free trade agreements (FTAs), known as international investment agreements (IIAs), have been the primary tools for promoting and protecting international investment. This report answers frequently asked questions about U.S. IIAs including provisions for investor- state dispute settlement. Congressional Research Service International Investment Agreements (IIAs): Frequently Asked Questions Contents Background and Context ................................................................................................................. 1 What is foreign direct investment (FDI)? ................................................................................. 1 What is the composition and size of FDI? ................................................................................ 1 What is the relationship between -

Assessment Maine Citizen's Trade Policy Commission, 2009

Assessment Maine Citizen’s Trade Policy Commission, 2009 William Waren1 January 27, 2010 Outline & Table of Contents Page Summary of Analysis 3 Preface: Vague Standards, Unpredictable Tribunals, Missing Data 8 Assessing the Impacts of International Trade Agreements on State and Municipal Laws in Maine 9 International Investment Agreements 11 Introduction General Analysis of International Investment Agreements 12 Coverage: Definition of Investment Rules: Expropriation Rules: Minimum Standard of Treatment Exceptions Case Study: Maine Water Policy 14 Recent Developments 16 2008 Campaign Promise by Barack Obama U.S. House Ways and Means Committee Hearing U.S. State Department BIT Review Committee Report Ruling in Glamis Gold Pending Agreements: Colombia, Panama, Korea, Trans-Pacific Partnership, China Bilateral Investment Treaty International Services Agreements 21 Introduction General Analysis 21 Case Study: Maine Water Policy 22 Recent Developments 25 March 2009 Report: Working Party on Domestic Regulation Maine Citizens Trade Policy Commission communications. Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (Notification Provisions) 27 Introduction General Analysis 27 Case Study: Chinese Objection to Proposed State 1 Policy Director, Forum on Democracy & Trade, (202) 662-4236, [email protected]. 1 Product Safety and Electronic Waste Legislation 28 Recent Developments 30 NCSL resolution Maine Commission communications International Subsidies Agreements 32 Introduction General Analysis 32 Case Study: The Foreign Sales Corporation Case 33 Recent -

BIWATER ANNUAL 2008 GAZZA.Qxd:BIWATER ANNUAL 2007

Annual Report & Accounts 2007 - 2008 www.biwater.com Biwater Plc Biwater Plc provides the full spectrum of water and wastewater treatment worldwide. Biwater’s expertise includes: • Water and Wastewater Treatment • Membrane Technology and Desalination • Consultancy and Water Asset Management • Infrastructure Ownership, Investment & Operation • Package Plants and Products • Leisure Established in 1968, Biwater currently operates as a group of companies in over 30 countries, sharing the specialist knowledge and international experience that provides millions of people around the world with clean, safe drinking water and wastewater services. Biwater’s mission statement is: To maintain a world class reputation “ in all our business activities, founded on “the highest standards of customer service, ethics and environmental care. 1 Biwater Plc Annual Report 2008 Contents Company Information 3 Chairman’s Statement 4-5 Business Review 6-14 Directors Report 15-16 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in Respect of the Annual Report and the Financial Statements 17 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Members of Biwater Plc 18-19 Group Profit and Loss Account Year ended 31 March 2008 20 Group Balance Sheet 31 March 2008 21 Company Balance Sheet 31 March 2008 22 Group Cash Flow Statement Year ended 31 March 2008 23 Statement of Total Recognised Gains & Losses Year ended 31 March 2008 24 Accounting Policies 25-28 Notes to the Financial Statements 29-53 Principal Group Undertakings 54 Biwater Plc Annual Report 2008 2 Company Information Board of Directors -

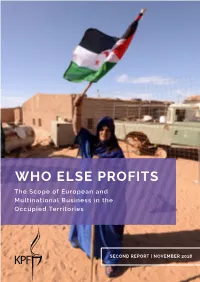

Who Else Profits the Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories

WHO ELSE PROFITS The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories SECOND RepORT | NOVEMBER 2018 A Saharawi woman waving a Polisario-Saharawi flag at the Smara Saharawi refugee camp, near Western Sahara’s border. Photo credit: FAROUK BATICHE/AFP/Getty Images WHO ELse PROFIts The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories This report is based on publicly available information, from news media, NGOs, national governments and corporate statements. Though we have taken efforts to verify the accuracy of the information, we are not responsible for, and cannot vouch, for the accuracy of the sources cited here. Nothing in this report should be construed as expressing a legal opinion about the actions of any company. Nor should it be construed as endorsing or opposing any of the corporate activities discussed herein. ISBN 978-965-7674-58-1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 WORLD MAp 7 WesteRN SAHARA 9 The Coca-Cola Company 13 Norges Bank 15 Priceline Group 18 TripAdvisor 19 Thyssenkrupp 21 Enel Group 23 INWI 25 Zain Group 26 Caterpillar 27 Biwater 28 Binter 29 Bombardier 31 Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. 33 Western Union 35 Transavia Airlines C.V. 37 Atlas Copco 39 Royal Dutch Shell 40 Italgen 41 Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica 43 NAgoRNO-KARABAKH 45 Caterpillar 48 Airbnb 49 FLSmidth 50 AraratBank 51 Ameriabank 53 ArmSwissBank CJSC 55 Artsakh HEK 57 Ardshinbank 58 Tashir Group 59 NoRTHERN CYPRUs 61 Priceline Group 65 Zurich Insurance 66 Danske Bank 67 TNT Express 68 Ford Motor Company 69 BNP Paribas SA 70 Adana Çimento 72 RE/MAX 73 Telia Company 75 Robert Bosch GmbH 77 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION On March 24, 2016, the UN General Assembly Human Rights Council (UNHRC), at its 31st session, adopted resolution 31/36, which instructed the High Commissioner for human rights to prepare a “database” of certain business enterprises1. -

Corporate Profile 01?Wd

Corporate Profile 01?wd Cascal (NYSE: HOO) At a glance: Cascal is a specialist investor and operator of water and wastewater Exchange: NYSE systems. Ticker: HOO Price (3/19/09): $3.32 Cascal was formed in April 2000, and at the time brought together all Market Cap: $101.4 mil of Biwater’s operational contracts in a single company. Cascal is a 52 Wk High: $15.19 subsidiary of the Biwater Group but since January 2008 has some of 52 Wk Low: $2.07 its shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). Shares Outstanding: 30.57 mil Cascal continues to build upon its global reputation for service, innovation and environmental responsibility and has an extensive Investment Considerations: knowledge of the international water market. • A global pure-play water and Cascal invests in and operates water and wastewater facilities wastewater asset owner. worldwide. The company has experience is currently working in seven • Ranked the second best UK Water countries across four continents where its mission is to deliver high Company in terms of overall quality water services. performance. • Solid international growth portfolio Whether it is the operation and development of existing utilities or the (40% of sales in high growth creation of new facilities, Cascal provides efficiency, innovation, international markets). performance and customer satisfaction. • Strong demand for private sector capital and expertise to meet higher water quality and environmental standards to achieve greater Services efficiency. • Water utility industry low risk due to Cascal: strict regulations, stable demand • Provides water services to over 4.3 million people drivers (population increase) and • Employs over 2,700 staff long-term contracts. -

State Dispute Settlement

UNCTAD/WEB/DIAE/IA/2009/6/Rev1 UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Geneva Latest Developments in Investor– State Dispute Settlement IIA MONITOR No. 1 (2009) International Investment Agreements UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 1 IIA MONITOR No. 1 (2009) Latest Developments in Investor–State Dispute Settlement∗ I. Recent trends In 2008, the number of known treaty-based investor–state dispute settlement cases filed under international investment agreements (IIAs) grew by at least 30, bringing the total number of known treaty-based cases to 317 by the end of 2008 (figure 1).1 Although this constitutes a slight decrease from 2007 (when 35 new cases were filed), it continues a trend that began in 2002, with between 28 and 48 new cases every year, indicating that international investment arbitration is no longer an exceptional phenomenon, but a part of the “normal” investment landscape. Since the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is the only arbitration facility to maintain a public registry of claims, the total number of actual treaty-based cases is likely to be higher.2 Of the total 317 known disputes, 201 were filed with ICSID (or the ICSID Additional Facility), 83 under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), 17 with the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, five with the International Chamber of Commerce and five were ad hoc. One further case was filed with the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration and one was administered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. In four cases, the applicable rules are unknown so far. -

APEC Training Workshop on Energy and Water Efficiency

APEC Training Workshop Energy and Water Efficiency in Water Supply: Practical Training on Proven Approaches Workshop Report Hanoi, Vietnam 9-10 March, 2010 APEC Energy Working Group May 2010 APEC Project EWG 12/2009A Produced by Alliance to Save Energy 1850 M Street, NW Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036 United States For Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat 35 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119616 Tel: (65) 68919 600 Fax: (65) 68919 690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.apec.org © 2010 APEC Secretariat APEC#210-RE-01.11 Workshop on Water and Energy Efficiency in Water Supply, March 9-10, 2010, Hanoi, Vietnam 2 Table of Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Workshop on Energy and Water Efficiency in Water Supply........................................................................ 4 Training Reference Materials ........................................................................................................................ 7 Feedback ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 Trainers’ Profiles .......................................................................................................................................... -

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes AWARD

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes ICSID CASE NO. ARB/05/22 BIWATER GAUFF (TANZANIA) LTD., CLAIMANT V. UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA, RESPONDENT AWARD RENDERED BY AN ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL COMPOSED OF GARY BORN, ARBITRATOR TOBY LANDAU QC, ARBITRATOR BERNARD HANOTIAU, PRESIDENT Date of dispatch to the parties: July 24, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER I. PARTIES AND GENERAL BACKGROUND TO THE DISPUTE .................... 1 CHAPTER II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................................................. 7 A. INSTITUTION OF THE PROCEEDINGS .......................................................................................... 7 B. FIRST SESSION OF THE TRIBUNAL AND PROCEDURAL ORDER NO. 1 ......................................... 9 C. FIRST REQUESTS FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS: PROCEDURAL ORDER NO. 2 ................ 13 D. CLAIMANT’S REQUEST FOR PROVISIONAL MEASURES ON CONFIDENTIALITY: PROCEDURAL ORDER NO. 3...................................................................................................... 13 E. CLAIMANT’S REQUEST FOR A SWORN STATEMENT FROM THE REPUBLIC: LETTER OF THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL DATED 22 NOVEMBER 2006.......................................................... 16 F. SECOND REQUESTS FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS: PROCEDURAL ORDER NO. 4 ............ 16 G. PETITION FOR AMICUS CURIAE STATUS: PROCEDURAL ORDER NO. 5 AND SUBSEQUENT PROCEDURE............................................................................................................................. 16 H. -

Privatisation of Water, Sanitation & Environment-Related Services In

PRIVATISATION OF WATER, SANITATION & ENVIRONMENT-RELATED SERVICES IN MALAYSIA Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Malaysia Office 1999 JICA...A Study of Privatisation in Malaysia TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................IX CHAPTER 1 A STUDY OF PRIVATISATION IN MALAYSIA: INTRODUCTION................... 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE OF WORK OF THE STUDY ........................................ 1-3 1.3 METHODOLOGY ADOPTED ........................................................................... 1-4 1.4 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................. 1-4 1.5 SCHEDULE OF WORK AND TASKS ................................................................ 1-8 CHAPTER 2 PRIVATISATION IN MALAYSIA: CONCEPT, POLICY AND PRACTISE ........ 2-1 2.1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................ 2-1 2.2 THE CONCEPT ............................................................................................ 2-2 2.3 THE RATIONALE .......................................................................................... 2-2 2.4 FUTURE DIRECTION..................................................................................... 2-3 2.5 PRIVATISATION POLICY AND PLAN ................................................................. 2-3 2.5.1 Privatisation -

Water Market Asia

Water Market Asia “In shallow waters, shrimps make fools of dragons.” Chinese Proverb (C) GWI 2006 - Reproduction Prohibited i Water Market Asia This report was researched, written and edited by Jensen & Blanc-Brude, Ltd. for Global Water Intelligence Jensen & Blanc-Brude, Ltd. Global Water Intelligence 22 Leathermarket Street, Unit 6 Published by Media Analytics, Ltd. London SE1 3HP The Jam Factory, 27 Park End Street United Kingdom Oxford OX1 1HU [email protected] United Kingdom www.jensenblancbrude.com [email protected] www.globalwaterintel.com While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, neither Global Water Intelligence, Jensen & Blanc-Brude Ltd or Media Analytics Ltd, nor any of the contributors accept liability for any errors or oversights. Unauthorised distribution or reproduction of the contents of this publication is strictly prohibited without the written permission of the publisher and authors. Contact Media Analytics Ltd or Jensen & Blanc-Brude Ltd for permission. Opportunities in the Water & Wastewater Sectors in Asia & the Pacifi c ii Water Market Asia Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following contributors to this report: Seungho Lee researched and wrote the South Korea profi le Michiko Iwanami researched and wrote the Japan profi le Marie Hélène Zerah researched and contributed to the India profi le Kathy Liu contributed to the China profi le The GWI team provided helpful comments and support. The authors also wish to thank the following practitioners -

Curriculum Vitae 履歷表

CURRICULUM VITAE 履歷表 Prepared in January 2017 Name 姓名 CHUA Hong 蔡宏 Current Appointment Dean, Faculty of Science and Technology, Technological and Higher Education Institute 現職 of Hong Kong, Vocational Training Council (2012 – date) 香港高等教育科技學院 科技學院院長 Senior Retained Consultant, Verde-Amazing Environmental Technology Group (1998 – date) 美倩環保科技有限公司 高級特聘顧問 Senior Retained Consultant, ETS-Testconsult Ltd. (2000 – date) 東業德勤測試顧問有限公司 高級特聘顧問 Recent Appointments Teaching Associate, Department of Chemical Engineering, National University of 近期工作經驗 Singapore (1988-1990) 新加坡國立大學 化學工程學系 教學助理 Research Fellow, Department of Biotechnology, Osaka University, Japan (1990-1992) 日本大阪大學 生物科技學系 研究員 Environmental Laboratories Officer, CSE Dept., Hong Kong Polytechnic University (1993-2000) 香港理工大學 土木及工程結構學系 環境實驗室 主任 Professor, Department of Civil and Structural Engineering, Hong Kong Polytechnic University (1992 – 2012) 香港理工大學 土木及工程結構學系 教授 Director, PolyU-HIT Joint Research Centre for Water and Wastewater Technology, Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2003 – 2012) 香港理工大學及哈爾濱工 業大學研究中心 主任 Director, Water and Waste Research and Development Centre, PolyU Shenzhen Technology Park, Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2010 – 2012) 香港理工大學 理大產學研究基地(深圳)有限公司 主任 Programme Co-ordinator for Academic Programme, B.Eng. (Hons.) in Civil and Environmental Engineering (successfully accredited by HKIE in October 2002), Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2001 – 2003) 香港理工大學 土木及環境工程學系 課程統籌 Programme Co-ordinator for Academic Programme, B.Eng. (Hons.) in Civil and Structural Engineering (successfully accredited by HKIE in April 2009), Hong Kong Polytechnic University (2007 – 2012) 香港理工大學 土木及工程結構學系 課程統籌 Tel : (852) 2176-1462 Fax : (852) 2176-1550 Email: [email protected] Content 目錄 1. Academic/Professional Qualifications/Scholarly Activities 學歷/專業資格/學術活動 2. Professional Experience 專業經驗 3. External Competitive R & D Grants 研發資助 4. Consultancy Projects 諮詢項目 5.