3. Invisible Renters As a Rule of Thumb, Both the Popular and Scholarly Literatures on Informal Housing Tend to Romanticize Squatters While Ignoring Renters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Settlements and Squatting in Romania: Socio-Spatial Patterns and Typologies

HUMAN GEOGRAPHIES – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography 7.2 (2013) 65–75. ISSN-print: 1843–6587/$–see back cover; ISSN-online: 2067–2284–open access www.humangeographies.org.ro (c) Human Geographies —Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography (c) The author INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS AND SQUATTING IN ROMANIA: SOCIO-SPATIAL PATTERNS AND TYPOLOGIES Bogdan Suditua*, Daniel-Gabriel Vâlceanub a Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest, Romania b National Institute for Research and Development in Constructions, Urbanism and Sustainable Spatial Development URBAN-INCERC, Bucharest, Romania Abstract: The emergence of informal settlements in Romania is the result of a mix of factors, including some social and urban planning policies from the communist and post-communist period. Squatting was initially a secondary effect of the relocation process and demolition of housing in communist urban renewal projects, and also a voluntary social and hous- ing policy for the poorest of the same period. Extension and multiple forms of informal settlements and squatting were performed in the post-communist era due to the inappropriate or absence of the legislative tools on urban planning, prop- erties' restitution and management, weak control of the construction sector. The study analyzes the characteristics and spatial typologies of the informal settlements and squatters in relationship with the political and social framework of these types of housing development. Key words: Informal settlements, Squatting, Forced sedentarization, Illegal building, Urban planning regulation. Article Info: Manuscript Received: October 5, 2013; Revised: October 20, 2013; Accepted: November 11, 2013; Online: November 20, 2013. Context child mortality rates and precarious urban conditions (UN-HABITAT, 2003). -

Slum Upgrading Strategies and Their Effects on Health and Socio-Economic Outcomes

Ruth Turley Slum upgrading strategies and Ruhi Saith their effects on health and Nandita Bhan Eva Rehfuess socio-economic outcomes Ben Carter A systematic review August 2013 Systematic Urban development and health Review 13 About 3ie The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) is an international grant-making NGO promoting evidence-informed development policies and programmes. We are the global leader in funding, producing and synthesising high-quality evidence of what works, for whom, why and at what cost. We believe that better and policy-relevant evidence will make development more effective and improve people’s lives. 3ie systematic reviews 3ie systematic reviews appraise and synthesise the available high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of social and economic development interventions in low- and middle-income countries. These reviews follow scientifically recognised review methods, and are peer- reviewed and quality assured according to internationally accepted standards. 3ie is providing leadership in demonstrating rigorous and innovative review methodologies, such as using theory-based approaches suited to inform policy and programming in the dynamic contexts and challenges of low- and middle-income countries. About this review Slum upgrading strategies and their effects on health and socio-economic outcomes: a systematic review, was submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of SR2.3 issued under Systematic Review Window 2. This review is available on the 3ie website. 3ie is publishing this report as received from the authors; it has been formatted to 3ie style. This review has also been published in the Cochrane Collaboration Library and is available here. 3ie is publishing this final version as received. -

Becoming Global and the New Poverty of Cities

USAID FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE BECOMING GLOBAL AND THE NEW POVER Comparative Urban Studies Project BECOMING GLOBAL AND THE NEW POVERTY OF CITIES TY OF CITIES This publication is made possible through support provided by the Urban Programs Team Edited by of the Office of Poverty Reduction in the Bureau of Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade, U.S. Agency for International Development under the terms of the Cooperative Lisa M. Hanley Agreement No. GEW-A-00-02-00023-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the Blair A. Ruble authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Woodrow Wilson Center. Joseph S. Tulchin Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars 1300 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, DC 20004 Tel. (202) 691-4000 Fax (202) 691-4001 www.wilsoncenter.org BECOMING GLOBAL AND THE NEW POVERTY OF CITIES Edited by Lisa M. Hanley, Blair A. Ruble, and Joseph S. Tulchin Comparative Urban Studies Project Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars ©2005 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC www.wilsoncenter.org Cover image: ©Howard Davies/Corbis Comparative Urban Studies Project BECOMING GLOBAL AND THE NEW POVERTY OF CITIES Edited by Lisa M. Hanley, Blair A. Ruble, and Joseph S. Tulchin WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, President and Director BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair; David A. Metzner, Vice Chair. Public Members: James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress; Bruce Cole, Chairman, National Endowment for the Humanities; Michael O. Leavitt, The Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Condoleezza Rice, The Secretary, U.S. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE SEMBCORP PROPOSES VOLUNTARY TENDER OFFER TO ACQUIRE SHARES IN CASCAL, A LEADING PROVIDER OF WATER AND WASTEWATER SERVICES - Irrevocable undertaking by majority shareholder, Biwater to tender its 58.4% shareholding - Offer price of US$6.75 per share, if at least 80% of the outstanding common shares have been validly tendered and not withdrawn or US$6.40 per share, if at least 17,868,543, but less than 80% of the outstanding common shares have been validly tendered and not withdrawn - Major milestone for Sembcorp in the fast-growing water sector SINGAPORE, April 26, 2010 – Sembcorp Industries Ltd (Sembcorp) today announces that its wholly owned subsidiary, Sembcorp Utilities Pte Ltd (Sembcorp Utilities) has entered into a tender offer and stockholder support agreement with Biwater Investments Limited (Biwater), to acquire Biwater’s 17,868,543 shares of Cascal N.V. (Cascal) (representing approximately 58.4% of the outstanding common shares of Cascal), a New York Stock Exchange-listed company and leading provider of water and wastewater services, and to launch a tender offer to acquire all of the outstanding common shares of Cascal. Tang Kin Fei, Group President & CEO of Sembcorp Industries said, “This acquisition will transform Sembcorp into a global water service provider and provide the platform for the Group to accelerate our growth in the future. We will have water and wastewater facilities in 31 operating locations in 11 countries around the world, and our water capacity in operation and 1 under development globally will increase by 50% from four million to close to six million cubic metres per day. -

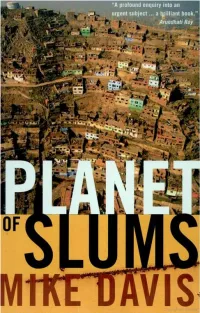

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

Homelessness in Developing Countries

The Nature and Extent of Homelessness in Developing Countries CARDO* University of Newcastle upon Tyne DFID Project No. R7905 * Now incorporated into the Global Urban Research Unit (GURU) Summary Highlights Homelessness in Developing Countries What is homelessness? The number of homeless people worldwide is estimated to be between 100 million and one billion, depending on how we count them and the definition used. However, little is known about the causes of homelessness or the characteristics of homeless people in developing countries. A study by CARDO* in the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, at the University if Newcastle upon Tyne, set out to explore the nature and extent of homelessness in nine developing countries. Most of the countries studied did not have had little or no reliable data on the numbers of homeless people. Several did not have any official definition of homelessness with which to conduct a census. In some countries, street sleepers are actually discounted for census purposes because they have no official house or address. The common perception of homeless people as unemployed, drunks, criminals, mentally ill or personally inadequate is inappropriate. In developing countries homelessness is largely a result of the failure of the housing supply system to address the needs of the rapidly growing urban population. The study found that homeless people: o Have often migrated to the city to escape rural poverty or to supplement rural livelihoods o Are generally employed in low paid, unskilled work o Often choose to sleep on the streets rather than pay for accommodation, preferring to send the money to their families o Are frequently harassed, evicted, abused or imprisoned o Suffer poor health with a range of respiratory and gastric illnesses o Are victims of crime, rather than perpetrators if it o Are predominantly lone males but increasingly couples and families with children Homeless women and children are most often the victims of family abuse. -

Riis's How the Other Half Lives

How the Other Half Lives http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES The Hypertext Edition STUDIES AMONG THE TENEMENTS OF NEW YORK BY JACOB A. RIIS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS CHIEFLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR Contents NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1890 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM Contents http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/contents.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES CONTENTS. About the Hypertext Edition XII. The Bohemians--Tenement-House Cigarmaking Title Page XIII. The Color Line in New York Preface XIV. The Common Herd List of Illustrations XV. The Problem of the Children Introduction XVI. Waifs of the City's Slums I. Genesis of the Tenements XVII. The Street Arab II. The Awakening XVIII. The Reign of Rum III. The Mixed Crowd XIX. The Harvest of Tare IV. The Down Town Back-Alleys XX. The Working Girls of New York V. The Italian in New York XXI. Pauperism in the Tenements VI. The Bend XXII. The Wrecks and the Waste VII. A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives XXIII. The Man with the Knife VIII.The Cheap Lodging-Houses XXIV. What Has Been Done IX. Chinatown XXV. How the Case Stands X. Jewtown Appendix XI. The Sweaters of Jewtown 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM List of Illustrations http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/illustrations.html LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Gotham Court A Black-and-Tan Dive in "Africa" Hell's Kitchen and Sebastopol The Open Door Tenement of 1863, for Twelve Families on Each Flat Bird's Eye View of an East Side Tenement Block Tenement of the Old Style. -

Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416

Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416 Prepared for: Submitted to: City of New York - Department of Parks and Recreation A.A.H. Construction Corporation Olmstead Center; Queens, New York 18-55 42nd Street Astoria, New York 11105-1025 and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Peebles Island, New York Prepared by: Alyssa Loorya, M.A., R.P.A., Principal Investigator and Christopher Ricciardi, Ph.D., R.P.A. for: Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, Incorporated October 2005 Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416 Prepared for: Submitted to: City of New York - Department of Parks and Recreation A.A.H. Construction Corporation Olmstead Center; Queens, New York 18-55 42nd Street Astoria, New York 11105-1025 and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Peebles Island, New York Prepared by: Alyssa Loorya, M.A., R.P.A., Principal Investigator and Christopher Ricciardi, Ph.D., R.P.A. for: Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, Incorporated October 2005 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Between September 2005 and October 2005, a Phase 1A Documentary Study and a partial Phase 1B Archaeological Monitoring was undertaken at Columbus Park, Block 165, Lot 1, New York, (New York County) New York. The project area is owned by the City of New York and managed through the Department of Parks and Recreation (Parks). The Parks’ Contract Number for the project is: M015-203MA. The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation’s (NYSOPRHP) File Number for the project is: 02PR03416. -

New York's Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian

FRUNZA, BOGDANA SIMINA., M.S. Streetscape and Ethnicity: New York’s Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian American Ethnic Identity. (2008) Directed by Prof. Jo R. Leimenstoll. 161 pp. The current research looked at ways in which the built environment of an ethnic enclave contributes to the definition and redefinition of the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. Assuming a dynamic component of the built environment, the study advanced the idea of the streetscape as an active agent of change in the definition and redefinition of ethnic identity. Throughout a century of existence, Little Italy – New York’s most prominent Italian enclave – changed its demographics, appearance and significance; these changes resonated with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. From its beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century until the present, Little Italy’s Mulberry Street has maintained its privileged status as the core of the enclave, but changed its symbolic role radically. Over three generations of Italian immigrants, Mulberry Street changed its role from a space of trade to a space of leisure, from a place of providing to a place of consuming, and from a social arena to a tourist tract. The photographic analysis employed in this study revealed that changes in the streetscape of Mulberry Street connected with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants, from regional Southern Italian to Italian American. Moreover, the photographic evidence demonstrates the active role of the street in the permanent redefinition of -

American Catholic Studies Ewslette

AMERICAN CATHOLIC STUDIES EWSLETTE CUSHWA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF AMERICAN CATHOLICISM Change ofHabit n 1993, Leslie Tentler criti tion of the women who supplied the excusable among historians of American cized the lack of historical unpaid labor for the parochial school women. In The Poor Belong to Us: attention paid to women system and a vast network of Catholic Catholic Charities and American Welfare religious. Considering the social service institutions. (1997), Dorothy Brown and Elizabeth vast numbers of educational, Several groundbreaking works have McKeown describe how Catholic charitable, and social service fostered an appreciation for the astonish women religious, while caring for institutions created and staffed ing achievements of Catholic women massive numbers of Catholic immi by American Catholic nuns, Tender religious in an age when society pre grants, contributed mightily to the observed, "Had women under secular or scribed narrowly limited roles for development of the American welfare Protestant auspices compiled this record women. In the 19th century, the con system. of achievement, they would today be a vent provided women with unequalled In Say Little, Do Much: Nurses, thoroughly researched population. But opportunities for education and au Nuns and Hospitals in the Nineteenth Catholic sisters are not much studied, tonomy; in fact, these studies are occa Century (2001), Sioban Nelson lifts what certainly not by women's historians or sionally tinged with wistfulness for a she calls the "veil of invisibility" on even, to any great extent, by historians time when Catholic women had more nursing nuns. Although women reli of American Catholicism." opportunities within the Church than gious founded and operated more than Nearly a decade has passed since outside of it. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Manhattan's Oldest Street: Part 3

November 10, 2014 Manhattan's Oldest Street: Part 3 As the Bowery continues to morph (most recently, the sale of a strip of lighting stores from 134-142 Bowery, above, portends redevelopment), Eastern Consolidated's Adelaide Polsinelli advises: Don't cry for old New York. The Bowery has been reinventing itself since Native Americans used it as a foot path to Canada. These lighting stores started as Federal-style rowhouses, and now, perhaps, the site is fated to become residential again. The inevitability of change is apparent in northern Chinatown's previous role as an entertainment district for monied Manhattanites and then the middle class, says New York Historical Tours' Kevin Draper. Take 104 and 106 Bowery, above. The area was a precedent to Lincoln Center until the Gilded Age chased the rich folk into their parlors and ballrooms. Then, the middle class took over. A theater in the basement of 104 and 106 has in its history hosted the first performance of Uncle Tom's Cabin and the first Yiddish theater in the US (which led to vaudeville, which spawned Broadway). Now, the buildings are a spa and a mobile phone store. A below-grade theater at the Crystal Hotel at 165 and 167 Bowery hosted the first-ever amateur night. Fifty years before the Apollo opened, a stagehand here would pull people off the stage with a cane, giving birth to the phrase “give him the hook.” Now, retail on the street is elevating, says Eastern Consolidated's Carlos Olson. SoHo- level rents are crossing Houston southward, like Anthropologie's more than $200/SF lease in 250 Bowery, a record south of Houston.