The Shaping of the Personal Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are Your Best Computer Options for Teleworking?

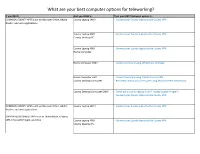

What are your best computer options for teleworking? If you NEED… And you HAVE a… Then your BEST telework option is… COMMON COUNTY APPS such as Microsoft Office, Adobe County Laptop ONLY - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Reader, and web applications County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN County Desktop PC County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Home Computer Home Computer ONLY - Connect remotely using VDI (Virtual Desktop) Home Computer AND - Connect remotely using Dakota County VPN County Desktop Computer - Remotely control your computer using Windows Remote Desktop County Desktop Computer ONLY - Check out a County laptop from IT Laptop Loaner Program - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN COMMON COUNTY APPS such as Microsoft Office, Adobe County Laptop ONLY - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Reader, and web applications SUPPORTED BUSINESS APPS such as OneSolution, OnBase, SIRE, Microsoft Project, and Visio County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN County Desktop PC If you NEED… And you HAVE a… Then your BEST telework option is… County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Home Computer Home Computer ONLY - Contact the County IT Help Desk at 651/438-4346 Home Computer AND - Connect remotely using Dakota County VPN County Desktop Computer - Remotely control your computer using Windows Remote Desktop County Desktop Computer ONLY - Check out a County laptop from IT Laptop Loaner Program - Connect your County laptop -

Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement

Scaling the Digital Divide Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement J a c o b V i g d o r a n d H e l e n l a d d w o r k i n g p a p e r 4 8 • j u n e 2 0 1 0 Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement Jacob L. Vigdor [email protected] Duke University Helen F. Ladd Duke University Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 Basic Evidence on Home Computer Use by North Carolina Public School Students 5 Access to home computers 5 Access to broadband internet service 7 How Home Computer Technology Might Influence Academic Achievement 10 An Adolescent's time allocation problem 10 Adapting the rational model to ten-year-olds 13 Estimation strategy 14 The Impact of Home Computer Technology on Test Scores 16 Comparing across- and within-student estimates 16 Extensions and robustness checks 22 Testing for effect heterogeneity 25 Examining the mechanism: broadband access and homework effort 29 Conclusions 34 References 36 Appendix Table 1 39 i Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the William T. Grant Foundation and the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), supported through Grant R305A060018 to the Urban Institute from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education for research support. They wish to thank Jon Guryan, Jesse Shapiro, Tim Smeeding, Andrew Leigh, and seminar participants at the University of Michigan, the University of Florida, Cornell University, the University of Missouri‐ Columbia, the University of Toronto, Georgetown University, Harvard University, the University of Chicago, Syracuse University, the Australian National University, the University of South Australia, and Deakin University for helpful comments on earlier drafts. -

Basic Electronics.COM -- Internet Guide to Electronics

BASIC ELECTRONICS.CD INFO Best Viewed at 800X600 Last Updated: January 10, 2003 Previously Internet Guide to Electronics Site. Welcome! This website allows you to NEW & NEWS: browse the subject of ELECTRONICS. If you are just starting the learning journey, I hope Your Projects you'll make use of the simple nature and graphical content of this site. Feel free to look Basic Electronics around. Don't worry -- there are no tests at the FAQ end of the day. If you would like to contact me regarding this site, email me at [email protected] John Adams - Author ( Place mouse over symbol to see selection in LCD screen then view explanation in the Email Me browser's status window. Non-Javascript browsers, scroll down for link explanations.) THEORY|APPLY IT!|COMPONENTS|MESSAGE BOARD|REF/DATA/TOOLS BOOKS/MAGs|LECTRIC LINKS|BASIC ELECTRONICS.CD INFO ABOUT|EMAIL|WHATS NEW! THEORY Gain the basic understanding of electronic principles that you will be making use of later. This includes Ohm's Law, Circuit Theory, etc. APPLY IT! Putting the theory to work. This includes sections on how to solder, multimeters, and of course, PROJECTS! COMPONENTS Learn about various electronics components. MESSAGE BOARD Post your basic electronics related questions here for others to answer and read. REFERENCE, DATA AND COOL TOOLS! Resistor color code info, plenty of calculators, chart, electronics data and other cool tools! VERY POPULAR PAGE BOOKS/MAGs A list of books and magazines relating to the subject of electronics. Includes direct links to amazon.com for ordering online. LECTRIC LINKS A list of top-rated Electronics-related sites on the Web. -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

Setup Outlook on Your Home Computer

Setup Outlook on your Home Computer Office 2010: 1. Run Microsoft Outlook 2010 2. When the startup wizard opens click Next. 3. When prompted to configure an E-mail Account select Yes and then click Next. 4. The Auto Account Setup will display next, select E-mail Account and fill in the information. Your password is your network password, the same one you use to log into computers on campus. After you fill the information in click Next. 5. Outlook will begin to setup your account; it may take a few minutes before the next window pops up. 6. You will be prompted with some sort of login screen. The one shown here offers 3 choices (Select the middle one if this is the case), but others may only offer 1. Type in the same username you use to login to campus computers but precede it with sdsmt\ Your password will be the same one you use to login on campus. Click OK to continue. 7. Outlook will finish setting up your account; this may take a few minutes. When it is done press the Finish button. 8. Outlook will start up and will begin to download your emails, contacts, and calendar from the server. This may take several minutes; there will be a green loading bar at the bottom of the window. Office 2007: 1. Run Microsoft Outlook 2007 2. When the startup wizard opens click Next. 3. When prompted to configure an E-mail Account select Yes and then click Next. 4. The Auto Account Setup will display next, select E-mail Account and fill in the information. -

VMS CRA Y Station Now Available It Is Now Possible to Submit Jobs Functions Closely

VMS CRA Y Station Now Available It is now possible to submit jobs Functions closely. It is implemented as a to the CRAY-1 from UCC's VAX/VMS The VMS station provides these series of commands entered in system. functions: response to the system's $ A CRAY-1 running the cos oper prompt. The commands look like ating system requires another -It submits jobs to the CRAY-1, VMS commands: they have pa computer to act as a "front-end" and returns output as a file un rameters and /qualifiers; they fol system. You prepare jobs and der the user's VMS directory. low much the same syntax and data on the front-end system, us -It transfers files between the interpretation rules (for example, ing whatever tools that system machines using the cos AC wild cards are handled correctly); provides, then submit the files as QUIRE and DISPOSE commands. and they prompt for required a batch job to the CRAY for proc The source of an ACQUIREd file parameters not present on the essing. Output is returned to the can be disk or tape; the desti command line. You can always front-end system for viewing. nation of a DISPOSEd file can recognize a station command, The software that runs on the be disk, tape, printer, or the though, because it always begins front-end machine to provide this VMS batch input queue. with the letter C. For example, communication is called a -At your option, it sends bulle the station command to submit a "station." tins to the terminal chronicling job to the CRAY is CSUBMIT. -

Personal Computing

Recent History of Computers: Machines for Mass Communication Waseda University, SILS, Science, Technology and Society (LE202) The communication revolution ‚ In the first period of the history of computers, we see that almost all development is driven by the needs and the financial backing of large organizations: government, military, space R&D, large corporations. ‚ In the second period, we will notice that the focus is now shifting to small companies, individual programers, hobbyists and mass consumers. ‚ The focus in the first period was on computation and control. In the second period, it is on usability and communication. ‚ A mass market for computers was created, through the development of a user-friendly personal computer. Four generations of computers 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Period 1940s–1955 1956–1963 1964–1967 1971–present ? Tech- vacuum transistors integrated micro- ? nology tubes circuits processors Size full room large desk sized desk-top, ? (huge) machine hand-held Software machine assembly operating GUI ? language language systems interface The microprocessor ‚ In 1968, the “traitorous seven” left Fairchild Semiconductor to found Intel. ‚ In 1969, Busicom, a Japanese firm, commissioned Intel to make a microprocessor for a handheld calculator. ‚ This lead to the Intel 4004. Intel bought the rights to sell the chip to other companies. ‚ Intel immediately began the process of designing more and more powerful microchips. Schematic: The Intel 4004 ‚ This has lead to computers small enough to fit in our hands. Consumer electronics ‚ The microprocessor made it possible to create more affordable consumer electronics. ‚ The Walkman came out in 1979. Through the 1980s video players, recorders and stereos were marketed. -

Do-It-Yourself Devices: Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products

Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis SB Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 2003 MA Interaction Design Interaction Design Institute Ivrea, June 2006 SM Media Arts and Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 2011 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2015 © 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All right reserved. Author: David A. Mellis Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 7, 2015 Certified by: Mitchel Resnick LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research Program in Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by: Pattie Maes Academic Head Program in Media Arts and Sciences Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning on August 7, 2015 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Many domains of DIY (do-it-yourself) activity, like knitting and woodworking, offer two kinds of value: the making process itself and using the resulting products in one’s life. With electronics, the sophistication of modern devices makes it difficult to combine these values. Instead, when people make electronics today, they generally use toolkits and other prototyping processes that aren’t well suited to extended use. This dissertation investigates digital fabrication (of both electronic circuit boards and enclosures) as an alternative approach to DIY electronics, one that can support individuals in both making devices and using them in their daily lives. -

The Cost of Using Computers

Summary: Students calculate and compare electrical costs of computers in various modes. Cost of Computers Grade Level: 5-8 Subject Areas: English Objectives puters, lights, and monitors when they’re not (Media and Technology, Research By the end of this activity, students will be in use reduces the number of comfort com- and Inquiry), Mathematics, able to plaints and air conditioning costs. Science (Physical) • explain that different types of computers use different amounts of electricity; There are many computer myths that have been dispelled over the years. One myth is Setting: Classroom • compare and contrast computer mode settings and their electricity use; and that screen-savers save energy. In fact, it Time: • identify ways to conserve electricity when takes the same amount of electricity to move that fish around your screen as it does to do Preparation: 1 hour using computers. any word processing. Activity: two 50-minute periods Rationale Vocabulary: Another myth is that it takes more energy to Calculating the cost of computers will help turn off and restart your computer than it Blended rate, CPU, Electric rate, students realize potential energy savings both does to just leave it on all the time. It is more Kilowatt-hour, Sleep mode, at school and at home. likely that your computer will be outdated Standby consumption, Watt, Watt before it is worn out by turning it off and on. meter Materials There are some school districts that require • Copies of Calculating Computer Costs Major Concept Areas: computers to be left on at night for software Activity Sheet upgrades and network maintenance; these • Quality of life • Calculator (optional) units are often automatically shut down after • Management of energy the upgrades are complete. -

Uni International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Inside the Computer Microcomputer Minicomputer Mainframe

Inside the computer Microcomputer Classification of Systems: • Personal Computer / Workstation. – Microcomputer • Desktop machine, including portables. – Minicomputer • Used for small, individual tasks - such as – Mainframe simple desktop publishing, small business – Supercomputer accounting, etc.... • Typical cost : £500 to £5000. • Chapters 1-5 in Capron • Example : The PCs in the labs are microcomputers. Minicomputer Mainframe • Medium sized server • Large server / Large Business applications • Desk to fridge sized machine. • Large machines in purpose built rooms. • Used for distributed data processing and • Used as large servers and for intensive multi-user server support. business applications. • Typical cost : £5,000 to £500,000. • Typical cost : £500,000 to £10,000,000. • Example : Scarlet is a minicomputer. • Example : IBM ES/9000, IBM 370, IBM 390. Supercomputer • Scientific applications • Large machines. • Typically employ parallel architecture (multiple processors running together). • Used for VERY numerically intensive jobs. • Typical cost : £5,000,000 to £25,000,000. • Example : Cray supercomputer 1 What's in a Computer System? Software • The Onion Model - layers. • Divided into two main areas • Hardware • Operating system • BIOS • Used to control the hardware and to provide an interface between the user and the hardware. • Software • Manages resources in the machine, like • Where does the operating system come in? • Memory • Disk drives • Applications • includes games, word-processors, databases, etc.... Interfaces Hardware • The chunky stuff! •CUI • If you can touch it... it's probably hardware! • Command Line Interface • The mother board. •GUI • If we have motherboards... surely there must be • Graphical User Interface fatherboards? right? •WIMP • What about sonboards, or daughterboards?! • Windows, Icons, Mouse, Pulldown menus • Hard disk drives • Monitors • Keyboards BIOS Basics • Basic Input Output System • Directly controls hardware devices like UARTS (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) - Used in COM ports. -

Ascii, Baudot, and the Radio Amateur

ASCII, BAUDOT AND THE RADIO AMATEUR George W. Henry, Jr. K9GWT Copyright © 1980by Hal Communications Corp., Urbana, Illinois HAL COMMUNICATIONS CORP. BOX365 ASCII, BAUDOT, AND THE RADIO AMATEUR The 1970's have brought a revolution to amateur radio RTTY equipment separate wire to and from the terminal device. Such codes are found in com and techniques, the latest being the addition of the ASCII computer code. mon use with computer and line printer devices. Radio amateurs in the Effective March 17, 1980, radio amateurs in the United States have been United States are currently authorized to use either the Baudot or ASCII authorized by the FCC to use the American Standard Code for Information serial asynchronous TTY codes. Interchange(ASCII) as well as the older "Baudot" code for RTTY com munications. This paper discusses the differences between the two codes, The Baudot TTY Code provides some definitions for RTTY terms, and examines the various inter facing standards used with ASCII and Baudot terminals. One of the first data codes used with mechanical printing machines uses a total of five data pulses to represent the alphabet, numerals, and symbols. Constructio11 of RTTY Codes This code is commonly called the Baudot or Murray telegraph code after the work done by these two pioneers. Although commonly called the Baudot Mark Ull s,.ce: code in the United States, a similar code is usually called the Murray code in other parts of the world and is formally defined as the International Newcomers to amateur radio RTTY soon discover a whole new set of terms, Telegraphic Alphabet No.