Uni International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Electronics.COM -- Internet Guide to Electronics

BASIC ELECTRONICS.CD INFO Best Viewed at 800X600 Last Updated: January 10, 2003 Previously Internet Guide to Electronics Site. Welcome! This website allows you to NEW & NEWS: browse the subject of ELECTRONICS. If you are just starting the learning journey, I hope Your Projects you'll make use of the simple nature and graphical content of this site. Feel free to look Basic Electronics around. Don't worry -- there are no tests at the FAQ end of the day. If you would like to contact me regarding this site, email me at [email protected] John Adams - Author ( Place mouse over symbol to see selection in LCD screen then view explanation in the Email Me browser's status window. Non-Javascript browsers, scroll down for link explanations.) THEORY|APPLY IT!|COMPONENTS|MESSAGE BOARD|REF/DATA/TOOLS BOOKS/MAGs|LECTRIC LINKS|BASIC ELECTRONICS.CD INFO ABOUT|EMAIL|WHATS NEW! THEORY Gain the basic understanding of electronic principles that you will be making use of later. This includes Ohm's Law, Circuit Theory, etc. APPLY IT! Putting the theory to work. This includes sections on how to solder, multimeters, and of course, PROJECTS! COMPONENTS Learn about various electronics components. MESSAGE BOARD Post your basic electronics related questions here for others to answer and read. REFERENCE, DATA AND COOL TOOLS! Resistor color code info, plenty of calculators, chart, electronics data and other cool tools! VERY POPULAR PAGE BOOKS/MAGs A list of books and magazines relating to the subject of electronics. Includes direct links to amazon.com for ordering online. LECTRIC LINKS A list of top-rated Electronics-related sites on the Web. -

Personal Computing

Recent History of Computers: Machines for Mass Communication Waseda University, SILS, Science, Technology and Society (LE202) The communication revolution ‚ In the first period of the history of computers, we see that almost all development is driven by the needs and the financial backing of large organizations: government, military, space R&D, large corporations. ‚ In the second period, we will notice that the focus is now shifting to small companies, individual programers, hobbyists and mass consumers. ‚ The focus in the first period was on computation and control. In the second period, it is on usability and communication. ‚ A mass market for computers was created, through the development of a user-friendly personal computer. Four generations of computers 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Period 1940s–1955 1956–1963 1964–1967 1971–present ? Tech- vacuum transistors integrated micro- ? nology tubes circuits processors Size full room large desk sized desk-top, ? (huge) machine hand-held Software machine assembly operating GUI ? language language systems interface The microprocessor ‚ In 1968, the “traitorous seven” left Fairchild Semiconductor to found Intel. ‚ In 1969, Busicom, a Japanese firm, commissioned Intel to make a microprocessor for a handheld calculator. ‚ This lead to the Intel 4004. Intel bought the rights to sell the chip to other companies. ‚ Intel immediately began the process of designing more and more powerful microchips. Schematic: The Intel 4004 ‚ This has lead to computers small enough to fit in our hands. Consumer electronics ‚ The microprocessor made it possible to create more affordable consumer electronics. ‚ The Walkman came out in 1979. Through the 1980s video players, recorders and stereos were marketed. -

Do-It-Yourself Devices: Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products

Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis SB Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 2003 MA Interaction Design Interaction Design Institute Ivrea, June 2006 SM Media Arts and Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 2011 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2015 © 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All right reserved. Author: David A. Mellis Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 7, 2015 Certified by: Mitchel Resnick LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research Program in Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by: Pattie Maes Academic Head Program in Media Arts and Sciences Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning on August 7, 2015 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Many domains of DIY (do-it-yourself) activity, like knitting and woodworking, offer two kinds of value: the making process itself and using the resulting products in one’s life. With electronics, the sophistication of modern devices makes it difficult to combine these values. Instead, when people make electronics today, they generally use toolkits and other prototyping processes that aren’t well suited to extended use. This dissertation investigates digital fabrication (of both electronic circuit boards and enclosures) as an alternative approach to DIY electronics, one that can support individuals in both making devices and using them in their daily lives. -

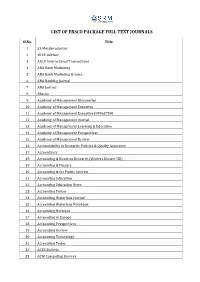

List of Ebsco Package Full Text Journals

LIST OF EBSCO PACKAGE FULL TEXT JOURNALS Sl.No. Title 1 33 Metalproducing 2 401K Advisor 3 AACE International Transactions 4 ABA Bank Marketing 5 ABA Bank Marketing & Sales 6 ABA Banking Journal 7 ABA Journal 8 Abacus 9 Academy of Management Discoveries 10 Academy of Management Executive 11 Academy of Management Executive (08963789) 12 Academy of Management Journal 13 Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 Academy of Management Perspectives 15 Academy of Management Review 16 Accountability in Research: Policies & Quality Assurance 17 Accountancy 18 Accounting & Business Research (Wolters Kluwer UK) 19 Accounting & Finance 20 Accounting & the Public Interest 21 Accounting Education 22 Accounting Education News 23 Accounting Forum 24 Accounting Historians Journal 25 Accounting Historians Notebook 26 Accounting Horizons 27 Accounting in Europe 28 Accounting Perspectives 29 Accounting Review 30 Accounting Technology 31 Accounting Today 32 ACES Bulletin 33 ACM Computing Surveys 34 ACM Transactions on Database Systems 35 Across the Board 36 Acta Sociologica (Taylor & Francis Ltd) 37 Active & Passive Electronic Components 38 Ad Age Global 39 Adhesives & Sealants Industry 40 AdMedia 41 Administrative Science Quarterly 42 Administrative Sciences (2076-3387) 43 Administrative Theory & Praxis (Administrative Theory & Praxis) 44 Administrative Theory & Praxis (M.E. Sharpe) 45 Advanced Composite Materials 46 Advanced Management Journal 47 Advanced Management Journal (03621863) 48 Advanced Packaging 49 Advances in Business-Related Scientific -

The Shaping of the Personal Computer

9780813345901-text_Westview Press 6 x 9 5/15/13 9:26 AM Page 229 10 THE SHAPING OF THE PERSONAL COMPUTER NO HISTORIAN HAS yet written a full account of the personal computer. Per- sonal computing was perhaps the most life-changing consumer phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century, and it continues to surprise in its ever-evolving applications and forms. If we consider an earlier invention, domestic radio, it took about fifty years for historians to start writing really satisfactory accounts. We should not expect to fully understand the personal computer in a lesser time scale. There has, of course, been no shortage of published accounts of the develop- ment of the personal computer by journalists. Much of this reportage is bad his- tory, though some of it makes for good reading. Perhaps its most serious distortion is its focus on a handful of individuals, portrayed as visionaries who saw the future and made it happen: Apple Computer’s Steve Jobs and Microsoft’s Bill Gates figure prominently in this genre. By contrast, IBM and the established computer firms are usually portrayed as dinosaurs: slow-moving, dim-witted, deservedly extinct. When historians write this history, it will be more complex than these journalistic ac- counts. The real history lies in the rich interplay of cultural forces and commercial interests. RADIO DAYS If the idea that the personal computer was shaped by an interplay of cultural forces and commercial interests appears nebulous, it is helpful to compare the develop- ment of the personal computer with the development of radio in the opening decades of the twentieth century, whose history is well understood. -

Phoenix PCUG Master August 2016 Master.Wps

Page 1 Phoenix PC Users Group, phoenixpcug.org/newsletters AUGUST` 2016 This website is gone: www.azacc.org The Arizona Alliance of Computer Clubs MAPS TO MEETINGS on Page 18 West Side…………. Tue, Aug 16, 2016 College America, 9801 North Metro Pkwy E8, Phoenix, AZ East Side………….. Wed, Aug 17, 2016 Univ. of Advancing Technology, 2625 W Baseline Road, Tempe (one block west of Fry’s Electronics) Fountain Hills….…. Thur, Aug 18, 2016 Fountain Hills Library, 12901 N La Montana Drive, Fountain Hills, Arizona. Starts at 5:30 PM ! Phoenix PC Users Group Presentation this month: Computer Officers topics, Windows 10, Smart Phones, etc . President: David Yamamoto Vice President: Richard Elardo, PhD For date and time changes: Secretary: Chuck Lewis www.phoenixpcug.org Treasurer: Paul Jamtgaard USE STRONG PASSWORDS! Do updates: Staff Members Membership Coordinator: Open Position Webmaster: Bill Aulepp INSIDE THIS ISSUE...........….............PAGE Fountain Hills Coordinator: Nancy Ogden East Side Coordinator: Open Position Aug 2016 Meetings Calendar ........…..…......3 West Side Coordinator: Bill Aulepp 1. Phoenix PCUG President’s Info …..……………4 Public Relations: Open Position 2. Still free Windows 10! ……………………………4 Newsletter Publisher: Bill Aulepp 3. 10 compelling reasons ..…………………………5 Newsletter Editor: David Yamamoto 4. Windows 10 Quick Reference ……………….…6 5. Opera wants you to ditch.…………………….…6 Contact Information 6. Chinese takeover of Opera ……………………..7 7. What is QuadRooter …………………………..…8 David Yamamoto: President (AT)PhoenixPCUG.org 8. Inside the NSA's War ..…….…….….….….…….8 Richard Elardo Vicepres(AT)PhoenixPCUG.org 9. Light Detection And Ranging LIDAR …….…..11 Chuck Lewis: Secretary(AT)PhoenixPCUG.org 10. EDUCATION, WOMEN……………...............…11 Paul Jamtgaard: Treasurer(AT)PhoenixPCUG.org 11. -

Popular Electronics

ROAD RALLY TIME-SIGNAL RECEIVER JULY POPULAR 1968 CENTS ELECTRONICS BEST WAY TO TUNE YOUR BASS REFLEX NEW APPROACH TO COLOR TV SERVICING TRANSISTOR TESTING WITH YOUR VTVM NOVEL CW MONITOR-$2 STEREO PHONES TEST POINTS FOR PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE Monitor Your Heart Action and Blood Flow (see page 27) 11111111111111111111 111111111111111111111Ba INTEt1SITY FOCU'r Ai 498000EINDISt 1 1E9 0/203 www.americanradiohistory.comAmericanRadioHistory.Com You get more for your money from NRI- America's oldest and largest Electronic, Radio -Television home -study school Compare. You'll find -as have so many Shown below is a dramatic, pictorial ex- thousands of others -NRI training can't ample of training materials in just one NRI be beat. From the delivery of your first les- Course. Everything you see below is in- sons in the remarkable, new Achievement cluded in low -cost NRI training. Other ma- Kit, to "bite size," easily -read texts and jor NRI courses are equally complete. Text carefully designed training equipment ... for text, kit for kit, dollar for dollar -your NRI gives you more value. best home -study buy is NRI. All this is yours -from Achieve- Approved under GI BILL ment Kit to the only Color TV If you served since Jan. 31, specifically designed for train- 1955, or are in service, check GI postage -free card. ing -when you enroll for N RI's line in TV -Radio Servicing course. Other courses are equally com- plete. But NRI training is more than kits and "bite- size" texts. It's also personal services which have made NRI a 50 year leader in the home -study field. -

Alan Milstein's History of Computers

Alan Milstein's History of Computers CYBERCHRONOLOGY INTRODUCTION This chronology reflects the vision that the history of computers is the history of humankind. Computing is not just calculating; it is thinking, learning, and communicating. This Cyberchronolgy is a history of two competing paths, the outcome of which may ultimately determine our fate. Computers either are simply machines to be controlled by the powerful, by governments and industrial giants, and by the Masters of War, or they are the tools that will allow every human being to achieve his or her potential and to unite for a common purpose. Day One Earliest humans use pebbles to calculate, a word derived from the Latin for “pebble” 17th century B.C. Wolf’s jawbone carved with 55 notches in groups of five, first evidence of tally system 8500 B.C. Bone carved with notches in groups of prime numbers 5th century B.C. Abacus invented, a digital computing device 415 B.C. Theaetetus creates solid geometry 293 B.C. Euclid writes the “Elements” 725 A Chinese engineer and Buddhist monk build first mechanical clock 1617 John Napier invents Napier’s Bones, multiplication tables on strips of wood or bones 1621 William Oughtred invents slide rule, an analog computing device 1623 Wilhelm Schickard of Germany invents calculating clock, a 6 digit machine, can add and subtract 1645 Blaise Pascal invents Pascaline, a 5 digit adding machine 1668 Samuel Morland of England invents nondecimal adding machine 1694 Gottfried Leibniz, who discovered both calculus and the binary system, develops the Leibniz Computer, a nonprogrammable multiplying machine 1714 Henry Mill patents the typewriter in England 1786 Mueller conceives Difference Engine, special purpose calculator for tabulating values of polynomial 1821 Michael Faraday, the Father of Electricity, builds first two electric motors 1832 Charles Babbage designs first Difference Engine 1835 Joseph Henry invents electrical relay 5/24/1844 Samuel B. -

Business Groups As Natural States

Department of Economics Working Paper Series Disintermediation: the Rise of the Personal Computer and the Internet in the Late Twentieth Century by Richard N. Langlois University of Connecticut Working Paper 2021-12 July 2021 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed in RePEc, http://repec.org Disintermediation: the Rise of the Personal Computer and the Internet in the Late Twentieth Century Richard N. Langlois [email protected] Department of Economics The University of Connecticut Storrs, CT 06269-1063 USA July 2021 ABSTRACT This paper is an excerpt from a larger book project called The Corporation and the Twentieth Century, which chronicles and interprets the institutional and economic history – the life and times, if you will – of American business in the twentieth century. This excerpt details the history of the personal computer industry and the Internet. It highlights the process of entrepreneurship and decentralized learning in these industries, and it considers the role of industrial and trade polices (in both the U. S. and Japan) in semiconductors and the development of the Internet. The excerpt ends with a consideration of U. S. v. Microsoft at the close of the century. JEL: D23, F14, K21, L26, L4, L52, L63, N62, N82, O3, P12, P 14, P16 Keywords: Innovation; technological change; entrepreneurship; industrial policy; antitrust. Comments solicited. Please do not cite without permission of the author. Long before the 1960s, what was to become Silicon Valley had been built by hobbyists, tinkerers, radicals, and utopians.1 Between the wars, the San Francisco area was a haven for amateur radio hobbyists, driven in part by the nearby naval and maritime facilities that called for and generated skills in radio. -

1 Introducing Basic Network Concepts

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen BaseTech / Networking Concepts / team / 223089-4 / Blind Folio 0 1 Introducing Basic Network Concepts “In the beginning, there were no networks. Life was bad.” —MIKE MEYERS In this chapter, you will learn etworks are everywhere—or so it seems. You can hardly do anything with how to: Ndata that does not involve a network. Like the human networks that we are ■ Identify human and computer all part of, computer networks let us share information and resources. In business, networks the reliance on networks is even more pervasive than in homes or schools. ■ Describe the benefits of networks Networks help individuals and businesses alike save money, but they also help ■ Distinguish between the different types of networks create income. Without a doubt, networking within the home will catch on over the next few years as it has in business. Soon, nearly all individuals in even moderately developed nations will have networked components throughout their homes. Those that don’t will be netologically disadvantaged because they will not be able to learn or to function at the same level as those who are networked. In this chapter, you’ll begin by relating networks to situations and concepts you already know. Once you have a basic understanding of what networks are and what they can do, it helps if you can actually begin working with them. In fact, it is so helpful to learn the ropes of networking through hands-on guided practice that that’s what is planned for you here. You will play the role of an employee in a fictional company, and you’ll have to learn on the job. -

Popular R I Jim Build a 0011110 Welcome Trick -Or- Treaters Greeter with Spooky Sights and Sounds This Halloween

A HALLOWEEN TREAT FOR TRICK-OR-TREATERS Oc tober 1996 Popular r i Jim Build a 0011110 Welcome trick -or- treaters greeter with spooky sights and sounds this Halloween Usiug Digital Panel Meters Learn how to make your next project more accurate and attractive Build a Have your oscilloscope perform like ^gil, i?}.: -,, one that costs hundreds mo 4 GÈF}tSBAC H lo> J PUBLCATIO-J f J F iJi JJdfl Find out what they do, and bow $3.50 U.S. 71896 48784 to join the ranks yourself $3.9E CAN. AmericanRadioHistory.Com Better Designs rnr t,z ,, ?imp siew - Faster .^wEt9j>np,.á410 .i:7.,ç','*] Guaranteed with * Electronics Workbench! # 4)" Just click and drag to create and edit 11`1Í. schematics. Mix analog and digital devices in any combination with full True Mixed -Mode Power control over values, models and Connect any analog or digital device to any other device without limit. Only Electronics Workbench offers this Try scenarios and behavior. 'what if' professional power for under $2,000. fine tune effortlessly. And on- screen waveforms always match actual circuit Real-World Digital Real -world TTL and CMOS, complete with propagation response. You'll create better designs delays and fanout. Unique at this price. faster -Guaranteed! 32 -Bit Speed Guaranteed Satisfaction Integrated SPICE analog and native -mode digital simulation Join over 70,000 customers and experience the in full 32 -bit. Unique at this price. power, flexibility and value that only Electronics Workbench offers. Receive unequaled service and Real-World Results free, unlimited technical support by phone, fax, Unlimited supply of over 200 components and ICs and 350 e -mail, WWW, CompuServe and BBS. -

1 Oral History Interview with Paul Ceruzzi November 24, 2020 Via

Oral History Interview with Paul Ceruzzi November 24, 2020 Via Zoom Conducted by William Aspray Charles Babbage Institute 1 Abstract Ceruzzi discusses his upbringing, education at Yale and Kansas, and work at Texas Tech, Clemson, and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. Topics include his books on Aiken, Stibitz, and Zuse; on flight in the computing era; and on Tyson’s Corner; as well as the several editions of his general history of computing. He discusses the computer history community – individuals, Annals of the History of Computing, and the Society for History of Technology special interest group on computer history. This interview is part of a collection of interviews on the early history of the history of computing. Keywords: Texas Tech, Clemson, Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum, Korad Zuse, Tyson’s Corner, Annals of the History of Computing, SHOT Special Interest Group in Computers, Information, and Society. 2 Aspray: All right. So, this is the 24th of November 2020 with an oral history with Paul Ceruzzi, who's in his home in Maryland. I'm in my home in Boulder, Colorado, and we're doing this interview over Zoom. I thought we should start, Paul, by asking you to tell me the year you were born, where you were born, something about your parents and about siblings. Ceruzzi: Well, I was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1949 and lived in a suburb of Bridgeport. My parents: my mom was a housekeeper. My father worked for an insurance company. Bridgeport at that time was one of the most industrially advanced cities in the country: machine tools, aircraft parts, automobile parts, lots of what was advanced technology at the time.