YANBU, SAUDI ARABIA by Khalils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Logistics-Related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport

Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport THE STUDY ON MULTIMODAL TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS SYSTEM OF THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN REGION AND MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport 4.1 Introduction This chapter explores the current conditions of land transportation modes and facilities. Transport modes including roads, railways, and inland waterways in Egypt are assessed, focusing on their roles in the logistics system. Inland transport facilities including dry ports (facilities adopted primarily to decongest sea ports from containers) and to less extent, border crossing ports, are also investigated based on the data available. In order to enhance the logistics system, the role of private stakeholders and the main governmental organizations whose functions have impact on logistics are considered. Finally, the bottlenecks are identified and countermeasures are recommended to realize an efficient logistics system. 4.1.1 Current Trend of Different Transport Modes Sharing The trends and developments shaping the freight transport industry have great impact on the assigned freight volumes carried on the different inland transport modes. A trend that can be commonly observed in several countries around the world is the continuous increase in the share of road freight transport rather than other modes. Such a trend creates tremendous pressure on the road network. Japan for instance faces a situation where road freight’s share is increasing while the share of the other -

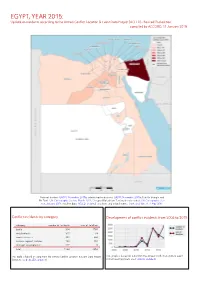

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

Urbanization and Agricultural Policy in Egypt

/.~C~~£82_1 09 034 FAER-169 URBAN'IZATIONAND A,G,RICULTURAL 'POLICY IN E,GYPT.CFOREIGN A~,' 'I RICULTURAL ECONOMIC REPT.) I JOHN B. PARKER, ET ALECONOMIC RESEA'R , ,CH SERVICE, WASHINGTON, DC' INTERNATION'AL ECONOMICS DIV. SEP 81 5' I ' 3P IljL IIIIIWIIII/I.A 11~lt6 . PS82-109.034 Oi"b.ni~ati'on and Agricultural Policy in Egypt (u.s.) .Economic Research Service Washington, DC Sep 81 . , y Z&t' i I U.s. .......[11111 I . PID NltiOhlLTeclMlifal. - . ·.Jli lillIS._ '..m.18' ' ...,. aacuMINTATION IL........... .' .'...... ,',.. :_ .... ,' ..,;> •. .:. ,1&. ' '... .. .111........ '1111 I.R .... .... , ..• _.MQI , .... '" FAE;R-169,.__"-____--...L__,._"__~.-1'1I8Z.J 0'_911''1 Ii~";";" .. 'rille............. .. ...... ~ Urbanization and Agricultural Policy In Egypy September 1981 . ...... ..,. 7.~ 8; ~ .,........I0Il IIept. No. John B. Parker and James R. Coyle FAER-169 .. ~.... 0 ........................ ~ In'ternatior~al Economics Division Economic Research Service II. ContnIct(C) or Gf!2nt(Q) No• . U.S. Department of Agriculture (C) ! Washington ~ D. C. 20250 (Q) ',. I'~ (Urnlt: 200 __) . '\.../ Policies related to agricultural production procurement in Egypt have pushed people out of rural areas while food subsidies have attracted them into cities. Urban growth in turn has caused substantial cropland loss, increased food imports, . - -.' ._"-_.- - --1 - ~ and led to political and economic/destabilization. Thi.s study eJ~amit:les the relatign ship between agricultural policy and the tremendous growth of urban areas, and pro poses changes in Egypt's agricultural pricing, food subsidy, and land use programs. 17. Document AlllllysIs I. Descriptors Agricultural production Policies Growth Procurement l.and use Urbanization It. -

Zone 25 Egypt H2

Cand # Name & Surname School Town R L U Total 830192 LAYAN MAHMOUD MOHAMED MOUSSA Nile Egyptian Schools - Minya Minya 33 27 28,5 88,5 832483 Judy Ayman Abdullah El Nasr Girls College Alexandria 32 22 30 84 817444 HAMZA MAHMOUD ABDEL-BAQY Nile Egyptian Schools - Minya Minya 33 22 28,5 83,5 817831 Abdullah Nasser Ali Mohamed Nile Egyptian Schools - Minya Minya 33 22 28,5 83,5 818974 Hosam Mohamed Gaber Hassan Nile Egyptian Schools - Qena Qena 33 22 28,5 83,5 820783 Eyad Elzab Nile Egyptian Schools - Port Said Port Said 33 22 28,5 83,5 820784 Eyad Elghazoly Nile Egyptian Schools - Port Said Port Said 33 22 28,5 83,5 820790 Yahya Mahmoud Nile Egyptian Schools - Port Said Port Said 33 22 28,5 83,5 820943 Mirna Samy Abdel-raouf Fahim Nile Egyptian Schools - Qena Qena 33 22 28,5 83,5 821525 Moaaz ibrahim abd el magid al nagar Tech. Center for Training, Consulting and InformationKafr El Sheikh 33 22 28,5 83,5 821853 Daniella Peter Adel Zakhary Nile Egyptian Schools - Qena Qena 33 22 28,5 83,5 821890 Solafa Moataz Wageh Mohamed Nile Egyptian Schools - Obour Qalubia 33 22 28,5 83,5 821894 Hana Ahmed Kamal Ahmed Ali Selim Nile Egyptian Schools - Obour Qalubia 33 22 28,5 83,5 821897 Malak Mohamed Abdel Azim Mohamed IbrahimNile Egyptian Schools - Obour Qalubia 33 22 28,5 83,5 826717 Malak Ahmed Mokhtar Futures - Othman Ibn Affan EL-Rehab 33 22 28,5 83,5 826724 Jana Ahmed Hassan Futures – Alshorouk Alshorouk 33 22 28,5 83,5 826726 Malak Abaas Makdid Futures – Alshorouk Alshorouk 33 22 28,5 83,5 826971 Nour Amr Saeed Shalaby Khodair Menofia 33 22 28,5 -

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2 Metlife Clinic - Cairo Medical Center 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Metlife Clinic 02 24509800 02 22580672 Hospital Heliopolis Emergency- 39 Cleopatra St. Salah El Din Sq., Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Cleopatra Hospital Gold Outpatient- 19668 Heliopolis Inpatient ( Except Emergency- 21 El Andalus St., Behind Cairo Heliopolis Hospital International Eye Hospital Gold 19650 Outpatient-Inpatient Mereland , Roxy, Heliopolis Emergency- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital San Peter Hospital Green 3 A. Rahman El Rafie St., Hegaz St. 02 21804039 02 21804483-84 Outpatient-Inpatient Emergency- 16 El Nasr st., 4th., floor, El Nozha Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Ein El Hayat Hospital Green 02 26214024 02 26214025 Outpatient-Inpatient El Gedida Cairo Medical Center - Cairo Heart Emergency- 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Silver 02 24509800 02 22580672 Center Outpatient-Inpatient Heliopolis Inpatient Only for 15 Khaled Ibn El Walid St. Off 02 22670702 (10 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital American Hospital Silver Gynecology and Abdel Hamid Badawy St., Lines) Obstetrics Sheraton Bldgs., Heliopolis 9 El-Safa St., Behind EL Seddik Emergency - Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Nozha International Hospital Silver Mosque, Behind Sheraton 02 22660555 02 22664248 Inpatient Only Heliopolis, Heliopolis 91 Mohamed Farid St. El Hegaz Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Al Dorrah Heart Care Hospital Orange Outpatient-Inpatient 02 22411110 Sq., Heliopolis 19 Tag El Din El Sobky st., from El 02 2275557-02 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Nozha st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 22738232 2 Samir Mokhtar st., from Nabil El 02 22681360- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Wakad st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 01225320736 Dr. -

THE EIGHT SITE and SERVICES / CORE HOUSE DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS of the ’70S� Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas Scoppa

A ROUNDTABLE WORKSHOP THE EIGHT SITE AND SERVICES / CORE HOUSE DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS OF THE ’70s" Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas Scoppa Reinhard Goethert Mar<n Scoppa GATHERING DATA WHEN ACCESS IS DIFFICULT – EXPERIMENTING WITH GOOGLE EARTH AS Goethert – SURROGATE! 1 1 A Seminar at Cairo University in 1979 documented eight demonstraon projects tesng new housing strategies WHAT HAPPENED TO THE Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas PROJECTS 35+ YEARS AFTER? Scoppa WHAT LESSONS CAN THEY TEACH US? Goethert – 2 Which project started like this? Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas Scoppa Goethert – 3 And what can we learn from this? HOW CAN WE FIND OUT? • Standard surveys with detailed family interviews and house to house assessment ideal BUT • Not a good <me considering the situaon • Substan<al preparaon, trained survey team, financial resources necessary to be credible Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas NEEDS CONSIDERABLE LEAD TIME Scoppa BUT STILL…. CAN WE FIND SOMETHING USEFUL QUICKLY? Goethert – Populaon con<nues to explode and cannot wait!!!! 4 Introduc<on to the Eight Projects • Ismailia • Suez City • Assiut Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas • Sadat City New Town • 10th of Ramadan New Town Scoppa • Helwan Housing Project Goethert – • Port Said 5 ISMAILIA DEMONSTRATION PROJECT/ ABU ATWA 6 Goethert – Scoppa Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas ISMAILIA DEMONSTRATION PROJECT/ EL HEKR 7 Goethert – Scoppa Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas Hai Al- Salam during the 1980s" Responsive Urbanism in Informal Areas Scoppa Goethert -

148041948.Pdf

' ' Seroprevalence of Babesia bovis, B-bigemina, Title Trypanosoma evansi, and Anaplasma marginale antibodies in cattle in southern Egypt Fereig, Ragab M., Mohamed, Samy G. A., Mahmoud, Hassan Y. A. H., AbouLaila, Mahmoud Rezk, Author(s) Guswanto, Azirwan, Thu-Thuy Nguyen, Mohamed, Adel Elsayed Ahmed, Inoue, Noboru, Igarashi, Ikuo, Nishikawa, Yoshifumi Citation Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases, 8(1): 125-131 Issue Date 2017 URL http://ir.obihiro.ac.jp/dspace/handle/10322/4579 This accepted manuscript is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non- Rights Commercial No Derivatives (by-nc-nd) License. <http://creativecommons.org/lisenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/> 帯広畜産大学学術情報リポジトリOAK:Obihiro university Archives of Knowledge Title Seroprevalence of Babesia bovis, B. bigemina, Trypanosoma evansi, and Anaplasma marginale antibodies in cattle in southern Egypt • Authors 1 2 3 • Ragab M. Fereig , Samy G. A. Mohamed , Hassan Y. A. H. Mahmoud , Mahmoud Rezk AbouLaila4, Azirwan Guswanto5, Thu-Thuy Nguyen6, Adel Elsayed Ahmed Mohamed7, Noboru Inoue8, Ikuo Igarashi9, Yoshifumi Nishikawa10* Addresses 1National Research Center for Protozoan Diseases, Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Inada-cho, Obihiro, Hokkaido 080-8555, Japan. Department of Animal Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, South Valley University, Qena City, Qena 83523, Egypt. Electronic address: [email protected]. 2Department of Animal Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, South Valley University, Qena City, Qena 83523, Egypt. Electronic address: [email protected]. 3Department of Animal Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, South Valley University, Qena City, Qena 83523, Egypt. Electronic address: [email protected]. 4Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Sadat City, 32511Sadat City, Minoufiya, Egypt. -

Striking Back

STRIKING BACK EGYPT’S ATTACK ON LABOUR RIGHTS DEFENDERS Cover Photo: Mai Shaheen Thousands of workers at Egypt's biggest textile company strike for minimum wage, payment of delayed bonuses, and a change in company leadership, Mahalla, February 2014. Table of Contents Executive Summary 5-9 I. Egyptian Labour: Resistance & Repression 10-13 II. Militarism & Poverty Under Sisi 14-15 III. Restrictive Legislation 16-18 IV. Case Study: French Naval Group and the Alexandria Shipyard Military Trial 19-27 V. Arrest, Detention, Imprisonment 28-30 VI. Threats to Lawyers & Lack of Representation 31-32 VII. Firing 33-34 VIII. Gendered Attacks 35-36 IX. Weaponizing Poverty 37 - 39 X. Assembly & Association 40-42 XI. Recommendations 43-45 “The government message right now is that striking does not get you rights, it gets you fired and on military trial.” - WHRD and labour leader “Workers are offered freedom for resigning from their jobs. But whether you’re in prison or free without a job, either way, your family has no money for food.” - Labour rights defender January 2019 Executive Summary Labour rights defenders in Egypt are facing more risks than they have in decades, according to interviews with human rights defenders (HRDs) conducted by Front Line Defenders. As increasing numbers of working class Egyptians on the side of the road outside Cairo, his body smeared descend into poverty in a struggling economy, labour with blood. rights activism demanding safe working conditions, a minimum wage and freedom of assembly is critical. Now one of the most dangerous topics in the country, However, the regime of President Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi labour rights was for decades Egypt’s most powerful has punished labour rights defenders with arrests, social mobiliser. -

Medhat M. Reda

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Ahmed Mohamed Nasr Mourad NATIONALITY: Egyptian ADDRESS: 3084 Zahraa Nasr City - Nasr City - Cairo DATE OF BIRTH: 13/01/1982 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] , [email protected] TELEPHONE: +201225736316 LANGUAGES: Arabic and English (Good) EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS . M.Sc., urban Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt, 2014. B.Sc., urban Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt, 2005. Member of Egyptian engineering Syndicate. KEY QUALIFICATION Almost eleven years of experience in regional planning field in preparing strategic national & regional plans for urban development (regions – governorates – regional corridors) planning, in urban planning field in implementing strategic master plan for existing cities and new urban community cities ,as well as in urban design field preparing subdivision planning for the residential, services and touristic areas, also preparing urban design planning for affordable and middle class housing projects, and in slums & unsafe areas development field performing actions plans to develop this areas .and working on Spatial &attributes analysis for the current situation using geographic information system programs (Arc GIS); preparing SWOT analysis and scenarios development using Microsoft office applications; preparing master & detailed plans using AutoCAD; drawings presentation using PSD; coordinating with other disciplines for various projects. EXPERIENCE . 2005–Date, SCALE Group for Communities -

Prof. Dr. Mahsoub Abdul Qadir Al Dawi

Curriculum Vitae Identification: Name: Mahsoub Abdel Qader Al Dhowey Hasan Birth Date and Place: May 15, 1972, Qena, Egypt. Faculty / Department: Faculty of Education / Educational Psychology dept. Position: Professor (2016) Address: - South Valley University, Faculty of Education, Qena, Egypt - Mobile: 01153622565 - E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Education: Ph.D., Educational Psychology (Educational & Psychological Statistics Major), South Valley University, Qena, Egypt (2004). M. A., Educational Psychology (Psychological Measurement Major), South Valley University, Qena, Egypt (2001). Special Diploma in Education, Qena Faculty of Education, South Valley University (1998). Bachelor of Science and Education, Mathematics Major, Assiut University (Qena Branch) (1994). Professional Experience: Professor of Educational Psychology: Qena Faculty of Education, South Valley University (2016). Assistant Professor of Educational Psychology: Qena Faculty of Education, South Valley University (2011). Accreditation Specialist: Education Reform Program (ERP), Academy for Educational Development, Head quarters, Cairo, Egypt, (2007-2009) with the following Responsibilities: 1. Initiate and maintain relations with Faculties of Specific Education, Faculties of Kindergarten and Faculty of Art Education Helwan University. 2. Conduct appropriate studies to analyze current situations and provide background documents for future planning. 3. Develop and implement annual work plans for introducing systems and policy changes in the area of education. 4. Prepare annual budgets and oversee expenditure. 5. Develop training packages on strategic planning and assessing academic programs in higher education. 6. Heading 4-day workshop on strategic planning. 7. Heading 3-day workshop on gap analysis for the academic programs. Professional and Organizational Development Advisor (POD): Education Reform Program, Academy for Educational Development, Egypt, Qena Office, (2006- 2007) with the following Responsibilities: 1. -

Adelhegazycv

CURRICULUM VITAE Name Adel El-Sayed Ahmed Hegazy Sex Male Date of birth 10 th of April, 1960 Place of birth Cairo, Egypt Nationality Egyptian Military service Finished military service 1983 Marital status Married Work address Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Research Institute (GEBRI), Sadat City University, Egypt. Profession Professor Job Description Director of Plant Tissue Culture and Genetic Engineering Center, Sadat City University, Egypt, 2004-2009. Director of the Central laboratory since, 2011. Consultant to JICA/Japan study team since, 2011. Agriculture Advisor and representative to JDI/JBEDC1/Japan since, 2011. Home address 25st Salah Salem. Ard El.Genenah, El.Zawia El.Hamra, Cairo, Egypt. 25st Ibrahim sakr. El-Akad, El- Mataria, Cairo, Egypt. Tel. Home 002-02- 24226670. Mobil 002- 1223996271. Work 002- 048- 2601264 (140). Fax 002- 048- 2601266/68 P.O. Box 79 Sadat City, Egypt. E-mail [email protected] Link http://gebrisadat.usc.edu.eg/Adel-Hegazy.htm http://jditokyo.com/en/index.html https://ag.purdue.edu/hla/Pages/Profile.aspx?strAlias=ahegazy QUALIFICATIONS: Ph. D. Plant Physiology, 2003. Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. Title Some Physiological Studies on Date Palm Micropropagation Through Direct Somatic Embryogenesis. M. Sc. Ornamental & Medicinal plants, 1992. Faculty of Agriculture, Al- Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. Title Tissue Culture Propagation of Strelitzia reginae Ait. Plant B. Sc. Horticulture, 1986. Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. TEACHING COURSES ( M. Sc. & Ph. D. Students): Plant Physiology. Advanced Plant Physiology. Plant Tissue Culture Methodology. Biochemistry of Plant Growth Regulators. Physiology of Plant Hormones. Modern Methods in Biotechnology of Pomology.