Dreams of Utopia in the Deserts of Egypt and Greater Cairo’S Chaotic Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2Nd Half FARA Report to Congress Ending December 31, 2007

U.S. Department of Justice . Washington, D.C. 20530 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the . Foreign Agents Registration Act . of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2007 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1-1 AFGHANISTAN......................................................1 ALBANIA..........................................................2 ALGERIA..........................................................3 ANGOLA...........................................................4 ARUBA............................................................5 AUSTRALIA........................................................6 AUSTRIA..........................................................8 AZERBAIJAN.......................................................9 BAHAMAS..........................................................11 BANGLADESH.......................................................12 BARBADOS.........................................................14 BELGIUM..........................................................15 BELIZE...........................................................16 BENIN............................................................17 BERMUDA..........................................................18 BOLIVIA..........................................................19 -

Dr. Amal Mahmoud Salem's CV

FACULTY FULL NAME AMAL MAHMOUD HUSSEIN SALEM POSITION Professor of Bioinformatics and Molecular Virology Personal Data Nationality |Egyptian Date of Birth |12/1/1968 Department |Biology Official Email | [email protected] Language Proficiency Language Read Write Speak Arabic Excellent Excellent Excellent English Excellent Excellent Excellent French Excellent Good Very good Academic Qualifications (Beginning with the most recent) Date Academic Degree Place of Issue Address 1990 BSc Cairo University Egypt 1994 MSc Cairo University-ORSTOM Egypt-France 2001 PhD Cairo University-CIRAD Egypt-France PhD, Master or Fellowship Research Title: (Academic Honors or Distinctions) PhD Biological and molecular characteristics of maize yellow stripe virus and its relationship with the leafhopper vector Master Characterization and serology of the leafhopper-borne maize yellow stripe tenuivirus in Egypt Fellowship Virus characterization and diagnosis, ORSTOM (Egypt-French project) Fellowship Molecular characterization and Bioinformatics analysis of MYSV (CIRAD Montpellier, France) Fellowship Bioinformatics analysis of CTV and its population structure (University of Davis-California, USA) Professional Record: (Beginning with the most recent) Job Rank Place and Address of Work Date Professor Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal Saudi Arabia 25-9-2019 Univ. Associate trainer certified by IBCT 19-9-2018 Associate professor Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal Saudi Arabia 3-1-2017 Univ. Head of Bioinformatics Dept. GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2015-2016 Director manger Alkhwarizmi Center for Egypt 2013 Bioinformatics, Egypt 1 Associate professor GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2012 Assistant professor GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2005 Lecturer GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2002 Post-Doc fellow UC-Davis USA 2001 Assistant lecturer Plant protection ins. Ministry of Egypt 1998 agric. -

Issue-8-21-2-2018.Pdf

www.meobserver.org 2 Home 21 Feb. 2018 EGYPS 2018 Egypt is moving into being a regional energy hub President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi inaugurated on Mon- day the second edition of Egypt Petroleum Show (EGYPS 2018) which took place from February 12 to 14, 2018 at Egypt International Exhibition Center (EIEC) in New Cairo City. The exhibition brought together the industry’s ma- jor companies and key players in the Region, provid- ing insights into the upcoming oil and gas opportuni- ties in Egypt and North Africa, from future licensing rounds, project requirements to short and long-term strategic plans and priorities. The conference tackled four main sectors Strategic, Technical, Women in En- ergy and the new Security in Energy, hosting over 150 expert speakers and attracting over 1,000 confer- ence delegates. Minister of Petroleum Tarek el-Molla said during his speech in the opening of EGYPS 2018 that EG- YPS 2018 is one of the ministry’s elements to show the world our successful stories and economic re- forms. Molla added that the EGYPS 2018 is an op- portunity to recognize current possibilities and in- crease co-operation with international companies and oil industry’s experts. Molla also referred to the economic reforms in Egypt such as the energy subsidies, Currency floata- tion and the development of investment legislation which aimed to increase the competitiveness of the national economy. The Ministry of Petroleum signed a coopera- tion agreement during the Conference, with Baker Hughes International Company to launch the opera- tions of Egypt Gate project to market the petroleum zones and oil discoveries, attracting international companies’ investments to these areas. -

A Revolution, a Change of Regime and 4 Rulers: Egypt’S Journey Through Washington’S Lobbies During the Decade of the Arab Spring

A revolution, a change of regime and 4 rulers: Egypt’s journey through Washington’s lobbies during the decade of the Arab Spring Part 1 SPECIAL REPORT Middle East Monitor is a not-for-profit media research institute that provides research, information and analyses of primarily the Palestine-Israel conflict. It also provides briefings on other Middle East issues. Its outputs are made available for use by journalists, academics and politicians with an interest in the Middle East and North Africa. MEMO aims to influence policy and the public agenda from the perspective of social justice, human rights and international law. This is essential to obtain equality, security and social justice across the region, especially in Palestine. MEMO wants to see a Middle East framed by principles of equality and justice. A revolution, a change It promotes the restoration of Palestinian rights, including the Right of Return, a Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital and with democratic rights upheld. It also advocates a nuclear-free Middle East. of regime and 4 rulers: By ensuring that policy-makers are better informed, MEMO seeks to have a Egypt’s journey through Washington’s lobbies greater impact on international players who make key decisions affecting the during the decade of the Arab Spring Middle East. MEMO wants fair and accurate media coverage of Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries. Translated from SasaPost Title: A revolution, a change of regime and 4 rulers Cover Image: Flags of Egypt and the US Published: March 2021 © MEMO Publishers 2021 [translation]. Original Arabic by Sasapost MEMO Publishers All rights reserved. -

Arab Contractors Mark

20 NEW VISION, Friday, November 23, 2018 ADVERTISER SUPPLEMENT Arab Contractors mark By Owen Wagabaza here is no corner of this country where the name Arab Contractors does not ring a bell. TThe construction company, which has a global footprint, has executed several projects in Uganda over the last 20 years. Arab Contractors Mahmoud Diaa Eldeen, is an Egyptian construction the technical manager of and contracting company Arab Contractors Uganda established in 1955 by Eng. Osman Ahmed Osman, an contractors in this technically Egyptian entrepreneur and challenging engineering politician who also served specialty and I can say his as Egypt’s housing minister dream came to fruition under the Anwar Sadat’s as currently Egyptian presidency. contractors are dominating Mahmoud Diaa Eldeen, the construction industry the technical manager of in Egypt, Middle East and Arab Contractors Uganda Africa,” he says. Ltd, says Osman foresaw the Diaa Eldeen adds that 7UXFNVWKDWDUHSDUWRI$UDE&RQWDFWRUVpHHW7KHoUPHQVXUHVWKDWLWVYHKLFOHVDUHLQVRXQGPHFKDQLFDOFRQGLWLRQ capabilities of the Egyptian their construction projects workforce by founding Arab in Egypt, Middle East and only way to pay tribute to nationalised after the high-profile projects. These International Airport, Borg Contractors and consequently Africa show the Egyptian his legacy is to go ahead Egyptian revolution of 1952 include Aswan High Dam, El Arab Stadium and Yasser Egyptian contractors have workforce’s capabilities and in our path of success by and is currently owned by the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Arafat International Airport. been able to undertake as a result, Osman’s name continuously adding value Egyptian government. Cairo Regional Ring Road, In Uganda, Arab Contractors many construction projects, has become a trademark for to our construction works And over the years, the Cairo-Alexandria desert road, have completed some of including bridges in many high quality, commitment and while at the same time company has participated Luxor International Airport, the most sophisticated yet parts of the world. -

The Political Economy of the New Egyptian Republic

ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻲ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ Hopkins The Political Economy of اﻹﻗﺘﺼﺎد اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻰ the New Egyptian Republic ﻟﻠﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﳉﺪﻳﺪة ﻓﻰ ﻣﺼﺮ The Political Economy of the New Egyptian of the New Republic Economy The Political Edited by ﲢﺮﻳﺮ Nicholas S. Hopkins ﻧﻴﻜﻮﻻس ﻫﻮﺑﻜﻨﺰ Contributors اﳌﺸﺎرﻛﻮن Deena Abdelmonem Zeinab Abul-Magd زﻳﻨﺐ أﺑﻮ اﻟﺪ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻋﺒﺪ اﳌﻨﻌﻢ Yasmine Ahmed Sandrine Gamblin ﺳﺎﻧﺪرﻳﻦ ﺟﺎﻣﺒﻼن ﻳﺎﺳﻤﲔ أﺣﻤﺪ Ellis Goldberg Clement M. Henry ﻛﻠﻴﻤﻨﺖ ﻫﻨﺮى إﻟﻴﺲ ﺟﻮﻟﺪﺑﻴﺮج SOCIAL SCIENCE IN CAIRO PAPERS Dina Makram-Ebeid Hans Christian Korsholm Nielsen ﻫﺎﻧﺰ ﻛﺮﻳﺴﺘﻴﺎن ﻛﻮرﺷﻠﻢ ﻧﻴﻠﺴﻦ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻣﻜﺮم ﻋﺒﻴﺪ David Sims دﻳﭭﻴﺪ ﺳﻴﻤﺰ Volume ﻣﺠﻠﺪ 33 ٣٣ Number ﻋﺪد 4 ٤ ﻟﻘﺪ اﺛﺒﺘﺖ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻰ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ أﻧﻬﺎ ﻣﻨﻬﻞ ﻻ ﻏﻨﻰ ﻋﻨﻪ ﻟﻜﻞ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺎرئ اﻟﻌﺎدى واﳌﺘﺨﺼﺺ ﻓﻰ ﺷﺌﻮن CAIRO PAPERS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE is a valuable resource for Middle East specialists اﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. وﺗﻌﺮض ﻫﺬه اﻟﻜﺘﻴﺒﺎت اﻟﺮﺑﻊ ﺳﻨﻮﻳﺔ - اﻟﺘﻰ ﺗﺼﺪر ﻣﻨﺬ ﻋﺎم ١٩٧٧ - ﻧﺘﺎﺋﺞ اﻟﺒﺤﻮث اﻟﺘﻰ ﻗﺎم ﺑﻬﺎ ﺑﺎﺣﺜﻮن and non-specialists. Published quarterly since 1977, these monographs present the results of ﻣﺤﻠﻴﻮن وزاﺋﺮون ﻓﻰ ﻣﺠﺎﻻت ﻣﺘﻨﻮﻋﺔ ﻣﻦ اﳌﻮﺿﻮﻋﺎت اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻴﺔ واﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎدﻳﺔ واﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ واﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺨﻴﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. ,current research on a wide range of social, economic, and political issues in the Middle East وﺗﺮﺣﺐ ﻫﻴﺌﺔ ﲢﺮﻳﺮ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﺑﺎﳌﻘﺎﻻت اﳌﺘﻌﻠﻘﺔ ﺑﻬﺬه اﻟﺎﻻت ﻟﻠﻨﻈﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻣﺪى ﺻﻼﺣﻴﺘﻬﺎ ﻟﻠﻨﺸﺮ. وﻳﺮاﻋﻰ ان ﻳﻜﻮن اﻟﺒﺤﺚ .and include historical perspectives ﻓﻰ ﺣﺪود ١٥٠ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ ﻣﻊ ﺗﺮك ﻣﺴﺎﻓﺘﲔ ﺑﲔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮر، وﺗﺴﻠﻢ ﻣﻨﻪ ﻧﺴﺨﺔ ﻣﻄﺒﻮﻋﺔ وأﺧﺮى ﻋﻠﻰ اﺳﻄﻮاﻧﺔ ﻛﻤﺒﻴﻮﺗﺮ (ﻣﺎﻛﻨﺘﻮش Submissions of studies relevant to these areas are invited. Manuscripts submitted should be أو ﻣﻴﻜﺮوﺳﻮﻓﺖ وورد). أﻣﺎ ﺑﺨﺼﻮص ﻛﺘﺎﺑﺔ اﳌﺮاﺟﻊ، ﻓﻴﺠﺐ ان ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ ﻛﺘﺎب ”اﻻﺳﻠﻮب ﳉﺎﻣﻌﺔ around 150 doublespaced typewritten pages in hard copy and on disk (Macintosh or Microsoft ﺷﻴﻜﺎﻏﻮ“ (The Chicago Manual of Style) ﺣﻴﺚ ﺗﻜﻮن اﻟﻬﻮاﻣﺶ ﻓﻰ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻛﻞ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ، أو اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ Word). -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events. -

Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report

Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities European Investment Bank L’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Construction Authority for Potable Water & Wastewater CAPW Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report Date of issue: May 2020 Consulting Engineering Office Prof. Dr.Moustafa Ashmawy Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project NTS ESIA Report Non - Technical Summary 1- Introduction In Egypt, the gap between water and sanitation coverage has grown, with access to drinking water reaching 96.6% based on CENSUS 2006 for Egypt overall (99.5% in Greater Cairo and 92.9% in rural areas) and access to sanitation reaching 50.5% (94.7% in Greater Cairo and 24.3% in rural areas) according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The main objective of the Project is to contribute to the improvement of the country's wastewater treatment services in one of the major treatment plants in Cairo that has already exceeded its design capacity and to improve the sanitation service level in South of Cairo at Helwan area. The Project for the ‘Expansion and Upgrade of the Arab Abo Sa’ed (Helwan) Wastewater Treatment Plant’ in South Cairo will be implemented in line with the objective of the Egyptian Government to improve the sanitation conditions of Southern Cairo, de-pollute the Al Saff Irrigation Canal and improve the water quality in the canal to suit the agriculture purposes. This project has been identified as a top priority by the Government of Egypt (GoE). The Project will promote efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in South Cairo and expand the reclaimed agriculture lands by upgrading Helwan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) from secondary treatment of 550,000 m3/day to advanced treatment as well as expanding the total capacity of the plant to 800,000 m3/day (additional capacity of 250,000 m3/day). -

Digital Transformation Table of 2019 Sustainability Highlights 04 CEO’S Note 06 Contents GB Auto Group at a Glance 08 Organisational Chart 14

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 Sustainability through Digital Transformation Table of 2019 Sustainability Highlights 04 CEO’s Note 06 Contents GB Auto Group at a Glance 08 Organisational Chart 14 Vision and Mission 16 Our Strategy for a Sustainable Business 18 Stakeholder Mapping 20 Management Approach 24 Alignment with International Standards 26 Excellence 28 Employee Engagement 30 Environmental Sustainability 36 Corporate Governance 40 Board of Directors 46 Social Contribution 50 3 Sustainability Highlights Sustainability Highlights GB Auto recognises the importance of technology and its capabilities as 1,483 video conference sessions as well as 91 automation completed processes were conducted in 2019. Digitising our Internal Processes GB Auto underwent changes in 2019 that heightened efficiency across operations and underlined the company’s commitment to sustainable development. The company saw through multiple initiatives in 2019 across key areas of sustainability, which it will continue capitalising on in the coming stage. GB Auto is in the process of initiating projects to replace diesel oil use with solar energy and natural gas across its operations, in an effort to reduce its carbon footprint and emissions. The project is expected to go live in September 2020 at the passenger cars assembly plant and bus Reducing Emissions manufacturing plant. In 2019, GB Auto began executing a new solar energy project at the pas- In 2019, the company began installing new ventilation systems at the senger cars assembly plant, with studies for further implementation held Badr City plant in the welding shop, and expects to finish the project by for Badr City, Sadat City and GB Polo. The project is expected to go live by October 2020. -

To Whom Do Minbars Belong Today?

Besieging Freedom of Thought: Defamation of religion cases in two years of the revolution The turbaned State An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt The report is issued by: Civil Liberties Unite August 2014 Designed by: Mohamed Gaber Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 Al Saraya Al Kobra St. First floor, flat number 4, Garden City, Cairo, Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Amr Ezzat: Researcher & Officer - Freedom of Religion and Belief Program Islam Barakat and Ibrahim al-Sharqawi helped to compile the material for this study. The Turbaned State: An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt Summary: Policies Regulating Mosques: Between the Assumption of Unity and the Reality of Diversity Along with the rapid political and social transformations which have taken place since January 2011, religion in Egypt has been a subject of much contention. This controversy has included questions of who should be allowed to administer mosques, speak in them, and use their space. This study observes the roots of the struggle over the right to administer mosques in Islamic jurisprudence and historical practice as well as their modern implications. The study then moves on to focus on the developments that have taken place in the last three years. The study describes the analytical framework of the policies of the Egyptian state regarding the administration of mosques, based on three assumptions which serve as the basis for these policies. -

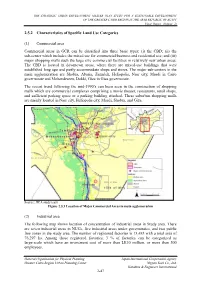

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

11. Egypt's Missing Millions

BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION RADIO 4 TRANSCRIPT OF “FILE ON 4” – “EGYPT’S MISSING MILLIONS” CURRENT AFFAIRS GROUP TRANSMISSION: Tuesday 15th March 2011 2000 - 2040 REPEAT: Sunday 20th March 2011 1700 - 1740 REPORTER: Fran Abrams PRODUCER: Ian Muir-Cochrane EDITOR: David Ross PROGRAMME NUMBER: 11VQ4873LHO 1 THE ATTACHED TRANSCRIPT WAS TYPED FROM A RECORDING AND NOT COPIED FROM AN ORIGINAL SCRIPT. BECAUSE OF THE RISK OF MISHEARING AND THE DIFFICULTY IN SOME CASES OF IDENTIFYING INDIVIDUAL SPEAKERS, THE BBC CANNOT VOUCH FOR ITS COMPLETE ACCURACY. “FILE ON 4” Transmission: Tuesday 15th March 2011 Repeat: Sunday 20th March 2011 Producer: Ian Muir-Cochrane Reporter: Fran Abrams Editor: David Ross ACTUALITY IN TAHRIR SQUARE ABRAMS: I’m standing in Tahrir Square, which was the focus for the protest which led to the fall of the President Hosni Mubarak here in Egypt last month. The atmosphere here today’s really quite cheerful. There’s a huge crowd, there’s a sea of flags, Egyptian flags everywhere and the people here really feel that they’ve got quite a lot to celebrate. But in tonight’s File on 4 I’m going to be investigating an issue which is still causing a rising sense of anger here is Egypt - corruption. ALBARDEI: Egypt was really unfortunately stolen, a lot of the wealth was stolen and this is a very poor country. I couldn’t see if a taxi driver that had a car accident should go to jail and somebody that stole a billion pounds should go scot free. ABRAMS: Since Hosni Mubarak was forced out, Cairo’s been awash with rumours about stolen money.