Downloaded At: Surveillance-DATAPSST-DCSS-Nov2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy

Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Cm 8715 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty October 2013 Cm 8715 £21.25 © Crown copyright 2013 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www. nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us [email protected] You can download this publication from our website at https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications ISBN: 9780101871525 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2593608 10/13 33233 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Contents Home Secretary Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 13 Our Strategic Response 25 PURSUE: Prosecuting and disrupting serious and 27 organised crime PREVENT: Preventing people from engaging 45 in serious and organised crime PROTECT: Increasing protection against 53 serious and organised crime PREPARE: Reducing the impact of serious and 65 organised crime Annex A: Accountability, governance and funding 71 Annex B: Departmental roles and responsibilities for 73 tackling serious and organised crime 4 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy Home Secretary Foreword 5 Home Secretary Foreword The Relentless Disruption of Organised Criminals Serious and organised crime is a threat to our national security and costs the UK more than £24 billion a year. -

Can Parliamentary Oversight of Security and Intelligence Be Considered More Open Government Than Accountability?

CAN PARLIAMENTARY OVERSIGHT OF SECURITY AND INTELLIGENCE BE CONSIDERED MORE OPEN GOVERNMENT THAN ACCOUNTABILITY? Stephen Barber ABSTRACT The nature of openness in government continues to be explored by academics and pub- lic managers alike while accountability is a fact of life for all public services. One of the last bastions of ‘closed government’ relates to the ‘secret’ security and intelligence ser- vices. But even here there have been significant steps towards openness over more than two decades. In Britain the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) of Parliament is the statutory body charged with scrutinising the agencies and since 2013 is more ac- countable itself to Westminster. This was highlighted by the first open evidence sessions involving the heads of the agencies which coincided with the unofficial disclosure of secret information by way of the so-called ‘WikiLeaks world’. This article examines scrutiny as a route to openness. It makes the distinction between accountability and open government and argues that the ‘trusted’ status of the ISC in comparison to the more independent Parliamentary Select Committees weakens its ability to hold govern- ment to account but, combined with the claim to privileged information and the acqui- escence of the agencies, makes its existence much more aligned to the idea of open gov- ernment Keywords - Westminster Select Committees, Intelligence and Security Committee, MI5 and MI6, scrutiny of public agencies. INTRODUCTION When the three heads of Britain’s security and intelligence services, Sir Iain Lobban (Director of GCHQ), Andrew Parker (Director General of MI5) and Sir John Sawers (Chief of MI6), appeared in Westminster on 7 November 2013, a new marker was set for open government. -

'Whitehall and the War on Terror: Lessons from the UK's Year

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Warwick Research Archives Portal Repository University of Warwick institutional repository This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Richard J. Aldrich. Article Title: Whitehall and the Iraq War: the UK's four Intelligence Enquiries. Year of publication: 2005 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.3318/ISIA.2005.16.1.73 Publisher statement: None Irish Studies in International Affairs, Vol.16, (2005) Whitehall and the Iraq War: The UK's Four Intelligence Enquiries Richard J. Aldrich* During a period of twelve months, lasting between July 2003 and July 2004, Whitehall and Westminster produced no less than four different intelligence enquiries. Each examined matters related to the Iraq War and the ‘War on Terror’. Although the term ‘unprecedented’ is perhaps over-used, we can safely say that such an intensive period of enquiry has not occurred before in the history of the UK intelligence community. The immediate parallels seemed to be in other countries, since similar investigations into ‘intelligence failure’ have been in train in the United States, Israel, Australia and even Denmark. These various national enquiries have proceeded locally and largely unconscious of each other existence. However, the number of different enquiries in the UK and the extent of the media interest recalls the ‘season of enquiry’ that descended upon the American intelligence community in 1975 and 1976.1 Although the intensity of the debate about connections between intelligence and the core executive was considerable, the overall results were less than impressive. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

Prism Vol. 9, No. 2 Prism About Vol

2 021 PRISMVOL. 9, NO. 2 | 2021 PRISM VOL. 9, NO. 2 NO. 9, VOL. THE JOURNAL OF COMPLEX OPER ATIONS PRISM ABOUT VOL. 9, NO. 2, 2021 PRISM, the quarterly journal of complex operations published at National Defense University (NDU), aims to illuminate and provoke debate on whole-of-government EDITOR IN CHIEF efforts to conduct reconstruction, stabilization, counterinsurgency, and irregular Mr. Michael Miklaucic warfare operations. Since the inaugural issue of PRISM in 2010, our readership has expanded to include more than 10,000 officials, servicemen and women, and practi- tioners from across the diplomatic, defense, and development communities in more COPYEDITOR than 80 countries. Ms. Andrea L. Connell PRISM is published with support from NDU’s Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS). In 1984, Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger established INSS EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS within NDU as a focal point for analysis of critical national security policy and Ms. Taylor Buck defense strategy issues. Today INSS conducts research in support of academic and Ms. Amanda Dawkins leadership programs at NDU; provides strategic support to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, combatant commands, and armed services; Ms. Alexandra Fabre de la Grange and engages with the broader national and international security communities. Ms. Julia Humphrey COMMUNICATIONS INTERNET PUBLICATIONS PRISM welcomes unsolicited manuscripts from policymakers, practitioners, and EDITOR scholars, particularly those that present emerging thought, best practices, or train- Ms. Joanna E. Seich ing and education innovations. Publication threshold for articles and critiques varies but is largely determined by topical relevance, continuing education for national and DESIGN international security professionals, scholarly standards of argumentation, quality of Mr. -

Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher Covert Operations in British Politics 1974-1978 Foreword

• Forward by Kevin McNamara MP • An Outline of the Contents • Preparing the ground • Military manoeuvres • Rumours of coups • The 'private armies' of 1974 re-examined • The National Association for Freedom • Destabilising the Wilson government 1974-76 • Marketing the dirt • Psy ops in Northern Ireland • The central role of MI5 • Conclusions • Appendix 1: ISC, FWF, IRD • Appendix 2: the Pinay Circle • Appendix 3: FARI & INTERDOC • Appendix 4: the Conflict Between MI5 and MI6 in Northern Ireland • Appendix 5: TARA • Appendix 6: Examples of political psy ops targets 1973/4 - non Army origin • Appendix 7 John Colin Wallace 1968-76 • Appendix 8: Biographies • Bibliography Introduction This is issue 11 of The Lobster, a magazine about parapolitics and intelligence activities. Details of subscription rates and previous issues are at the back. This is an atypical issue consisting of just one essay and various appendices which has been researched, written, typed, printed etc by the two of us in less than four months. Its shortcomings should be seen in that light. Brutally summarised, our thesis is this. Mrs Thatcher (and 'Thatcherism') grew out of a right-wing network in this country with extensive links to the military-intelligence establishment. Her rise to power was the climax of a long campaign by this network which included a protracted destabilisation campaign against the Liberal and Labour Parties - chiefly the Labour Party - during 1974-6. We are not offering a conspiracy theory about the rise of Mrs Thatcher, but we do think that the outlines of a concerted campaign to discredit the other parties, to engineer a right-wing leader of the Tory Party, and then a right-wing government, is visible. -

Read the Full PDF

Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism Gary J. Schmitt, Editor The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmitt, Gary James, 1952– Safety, liberty, and Islamist terrorism : American and European approaches to domestic counterterrorism / Gary J. Schmitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4333-2 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4333-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4349-3 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4349-6 (pbk.) [etc.] 1. United States—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations— United States. 3. National security—International cooperation. 4. Security, International. I. Title. JZ1480.A54S38 2010 363.325'16094—dc22 2010018324 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cover photographs: Double Decker Bus © Stockbyte/Getty Images; Freight Yard © Chris Jongkind/ Getty Images; Manhattan Skyline © Alessandro Busà/ Flickr/Getty Images; and New York, NY, September 13, 2001—The sun streams through the dust cloud over the wreckage of the World Trade Center. Photo © Andrea Booher/ FEMA Photo News © 2010 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

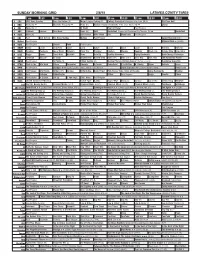

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Download Chapman Pincher: Dangerous to Know Free Ebook

CHAPMAN PINCHER: DANGEROUS TO KNOW DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Harry Chapman Pincher | 400 pages | 14 Feb 2014 | Biteback Publishing | 9781849546515 | English | London, United Kingdom Chapman Pincher - obituary Aitken, using information from retired CIA counterespionage chief James Jesus Angletonwrote a highly confidential letter in early to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcheroutlining Angleton's suspicions of Hollis acting as a double agent. A reprint of the first edition in He won awards as Journalist of the Year inand Reporter of the Decade in Henry Chapman Pincher British journalist. His father's family was from north Yorkshire and his father was serving in the Northumberland Fusiliers Chapman Pincher: Dangerous to Know Chapman was born. Because he didn't want her to know. Sign up here to see what happened On This Dayevery day in Chapman Pincher: Dangerous to Know inbox! His most cherished professional compliment came from his political opposite, the left-wing historian E. He died with his family by his side, talking about his time in espionage and the power it gave him in his career. BBC News. Inbunden Engelska, In this he was as assiduous as he was ruthless in exploiting and careful in protecting them. Enlarge cover. Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. During a stint in the army in the Second Chapman Pincher: Dangerous to Know War, Pincher developed an interest in weapons and how they worked — an interest which opened the door to an unexpected and exciting career. A good lunch". It was only the start of a career in which his name became synonymous with high-level exclusives from the most secret corners of government. -

Al-Qaeda's “Single Narrative” and Attempts to Develop Counter

Al-Qaeda’s “Single Narrative” and Attempts to Develop Counter- Narratives: The State of Knowledge Alex P. Schmid ICCT Research Paper January 2014 This Research Paper seeks to map efforts to counter the attraction of al Qaeda’s ideology. The aim is to bring together and synthesise current insights in an effort to make existing knowledge more cumulative. It is, however, beyond the scope of this paper to test existing counter-narratives on their impact and effectiveness or elaborate in detail a new model that could improve present efforts. However, it provides some promising conceptual elements for a new road map on how to move forward, based on a broad review and analysis of open source literature. About the Author Alex P. Schmid is a Visiting Research Fellow at the International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague, and Director of the Terrorism Research Initiative (TRI), an international network of scholars who seek to enhance human security through collaborative research. He was co-editor of the journal Terrorism and Political Violence and is currently editor-in-chief of Perspectives on Terrorism, the online journal of TRI. Dr. Schmid held a chair in International Relations at the University of St. Andrews (Scotland) where he was, until 2009, also Director of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV). From 1999 to 2005 he was Officer-in-Charge of the Terrorism Prevention Branch at the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in the rank of a Senior Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Officer. From 1994 to 1999, Dr. Schmid was an elected member of the Executive Board of ISPAC (International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council) of the United Nations' Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme. -

Defence and Security After Brexit Understanding the Possible Implications of the UK’S Decision to Leave the EU Compendium Report

Defence and security after Brexit Understanding the possible implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU Compendium report James Black, Alex Hall, Kate Cox, Marta Kepe, Erik Silfversten For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1786 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: HMS Vanguard (MoD/Crown copyright 2014); Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4, A Chinook Helicopter of 18 Squadron, HMS Defender (MoD/Crown copyright 2016); Cyber Security at MoD (Crown copyright); Brexit (donfiore/fotolia); Heavily armed Police in London (davidf/iStock) RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Defence and security after Brexit Preface This RAND study examines the potential defence and security implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision to leave the European Union (‘Brexit’). -

RAGHIDA DERGHAM With: HE Sir John Sawer HE Brett Mcgurk HR Rania Al Mashat HE Ambassador Yue Xiao Yong

TRANSCRIPT OF e-POLICY CIRCLE 10 July 8th, 2020 RAGHIDA DERGHAM With: HE Sir John Sawer HE Brett McGurk HR Rania Al Mashat HE Ambassador Yue Xiao Yong Youtube Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQvByHy92Ho&t=921s Raghida Dergham: Good morning San Francisco, very good morning and early morning, good afternoon London, Croatia and Cairo. I am in Beirut, and welcome to Beirut Institute Summit e-Policy Circle number 10, and we have a great cast with us today, of course. Sir John Sawer, former Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), former Permanent Representative of the UK at the UN where I got the pleasure of knowing you. Of course, right now you are the independent non-Executive Director of BP Global and Executive Chairman of Newbridge Advisory. Brett McGurk, who joined us last year at Beirut Institute Summit in Abu Dhabi, welcome to the e-Policy Circle. He is former Special Assistant to President George W. Bush and Senior Director of Iraq and Afghanistan, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Iraq and Iran, Special Presidential Envoy for the United States campaign against ISIS under President Barack Obama. He is now a Payne distinguished lecturer at Stanford University. Her excellency Rania Al Mashat is Egypt's Minister of International Cooperation, Former Minister of Tourism and previously Adviser to the chief economist of the IMF. And we have Ambassador Yue Xiao Yong, I hope I didn't butcher that, he's a China foreign expert, former Ambassador to Qatar, Jordan, and Ireland, he's Director and Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Studies at Redmond University of China, and he is now in Croatia, he's joining us from Croatia.