263-264 Contents Copia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dueling, Honor and Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Spanish Sentimental Comedies

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES Kristie Bulleit Niemeier University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Niemeier, Kristie Bulleit, "DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 12. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kristie Bulleit Niemeier The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the University of Kentucky By Kristie Bulleit Niemeier Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Spanish Literature Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kristie Bulleit Niemeier 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION DUELING, HONOR AND -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Saraband for Dead Lovers

Saraband for Dead Lovers By Helen de Guerry Simpson Saraband for Dead Lovers I - DUCHESS SOPHIA "I send with all speed," wrote Elizabeth-Charlotte, Duchesse d'Orléans, tucked away in her little room surrounded by portraits of ancestors, "to wish you, my dearest aunt and Serene Highness, joy of the recent betrothal. It will redound to the happiness of Hanover and Zelle. It links two dominions which have long possessed for each other the affection natural to neighbours, but which now may justly embrace as allies. It appears to me that no arrangement could well be more suitable, and I offer to the high contracting parties my sincerest wishes for a continuance of their happiness." The Duchess smiled grimly, dashed her quill into the ink, and proceeded in a more homely manner. "Civilities apart, What in heaven's name is the Duke of Hanover about? This little Sophie-Dorothée will never do; she is not even legitimate, and as for her mother, you know as well as I do that Eléonore d'Olbreuse is nothing better than a French she-poodle to whom uncle George William of Zelle treated himself when he was younger, I will not say more foolish, and has never been able to get rid of since. What, with all respect, was your husband thinking of to bring French blood into a decent German family, and connected with the English throne, too! In brief, my dearest aunt, all this is a mystery to me. I can only presume that it was concluded over your head, and that money played the chief role. -

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

À Beira Do Tempo E Do Espaço: Tradição E Tradução Da Espanha Em Murilo Mendes

Patrícia Riberto Lopes À BEIRA DO TEMPO E DO ESPAÇO: TRADIÇÃO E TRADUÇÃO DA ESPANHA EM MURILO MENDES Belo Horizonte Faculdade de Letras da UFMG 2008 Patrícia Riberto Lopes À BEIRA DO TEMPO E DO ESPAÇO: TRADIÇÃO E TRADUÇÃO DA ESPANHA EM MURILO MENDES. Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Letras, Estudos Literários. Área de concentração: Literatura Comparada. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Graciela Inés Ravetti de Gómez. Belo Horizonte Faculdade de Letras da UFMG 2008 Exame de tese LOPES, Patrícia Riberto. À beira do tempo e do espaço; tradição e tradução da Espanha em Murilo Mendes. Tese de Doutorado em Letras, Estudos Literários, apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2º. semestre de 2007. Banca examinadora Drª Graciela Inés Ravetti de Gómez – Orientadora (UFMG) Exame em ____ / ____ / ____ Conceito: ________________ Aos discípulos AGRADECIMENTOS À minha família, pela compreensão e apoio constantes, em especial ao Jander, pelo imenso amor. À professora Graciela Ravetti, pela orientação na medida certa e pelo visionarismo. Por sempre enxergar o humano, para além das circunstâncias. Aos membros da banca, pela gentileza de aceitarem o convite e por colaborarem no aperfeiçoamento deste trabalho. Aos professores do programa, pela generosidade em compartilhar conhecimentos e aos funcionários da FALE, pela colaboração. À equipe do Centro de Estudos Murilo Mendes, da UFJF, pela presteza no compartilhamento de informações. A flecha O motor do mundo avança: Tenso espírito do mundo, Vai destruir e construir Até retornar ao princípio. -

Media Matters: Reflections of a Former War Crimes Prosecutor Covering the Iraqi Tribunal Simone Monasebian

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 39 Issue 1 2006-2007 2007 Media Matters: Reflections of a Former War Crimes Prosecutor Covering the Iraqi Tribunal Simone Monasebian Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Recommended Citation Simone Monasebian, Media Matters: Reflections of a Former War Crimes Prosecutor Covering the Iraqi Tribunal, 39 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 305 (2007) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol39/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. MEDIA MATTERS: REFLECTIONS OF A FORMER WAR CRIMES PROSECUTOR COVERING THE IRAQI TRIBUNAL Simone Monasebian* Publicity is the very soul ofjustice. It is the keenest spur to exertion, and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself, while trying, under trial. Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. Gil Scott Heron, Flying Dutchmen Records (1974) I. THE ROAD TO SADDAM After some four years prosecuting genocidaires in East Africa, and almost a year of working on fair trial rights for those accused of war crimes in West Africa, I was getting homesick. Longing for New York, but not yet over my love jones with the world of international criminal courts and tri- bunals, I drafted a reality television series proposal on the life and work of war crimes prosecutors and defence attorneys. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Surrealist Masculinities

UC-Lyford.qxd 3/21/07 12:44 PM Page 15 CHAPTER ONE Anxiety and Perversion in Postwar Paris ans Bellmer’s photographs of distorted and deformed dolls from the early 1930s seem to be quintessential examples of surrealist misogyny (see Fig. 4). Their violently erotic Hreorganization of female body parts into awkward wholes typifies the way in which surrealist artists and writers manipulated and objectified femininity in their work. Bellmer’s manipulation and reconstruction of the female form also encourage comparison with the mutilation and reconstruction that prevailed across Europe during World War I. By viewing the dolls in this context, we might see their distorted forms as a displacement of male anxiety onto the bodies of women. Thus, Bellmer’s work—and the work of other male surrealists who de- picted fragmented female bodies—might reflect not only misogyny but also the disavowal of emasculation through symbolic transference. The fabrication of these dolls also expresses a link to consumer society. The dolls look as if they could be surrealist mannequins made by the prosthetic industry; their deformed yet interlocking parts reflect a chilling combination of mass-market eroticism and wartime bodily trauma. These connections between misogyny and emasculation anxiety, between eroticism and the horror of war trauma, and between consump- tion and desire are not specific to Bellmer’s idiosyncratic visual rhetoric, however. The practice of joining contradictory approaches and blurring boundaries between objects, identities, and media was more prevalent among the male surrealists than is usually acknowledged. If we open our eyes to consider these contrasts as part of a broader surrealist agenda, we can see how the surrealists aimed to destabilize their viewers’ assumptions about the boundaries 15 Copyrighted Material UC-Lyford.qxd 3/21/07 12:44 PM Page 16 FIGURE 4 Hans Bellmer, Poupée, 1935. -

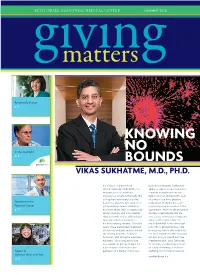

Knowing No Bounds Vikas Sukhatme, M.D., Ph.D

BETH ISRAEL DEACONESS MEDICAL CENTER SUMMER 2010 Renewable Energy p. 5 KNOWING NO In the Spotlight p. 9 BOUNDS VIKAS SUKHATME, M.D., PH.D. It’s diffi cult to pigeon-hole Most would disagree. Sukhatme’s Vikas P. Sukhatme, M.D., Ph.D., into ability to almost seamlessly usher any particular occupational scientifi c knowledge from one category—a situation that suits this fi eld to another and bring it to bear soft-spoken individualist just fi ne. on some of the most pressing Preeminence in A doctoral physicist who went on to problems in medicine has led to Prostate Cancer get his medical degree, Sukhatme groundbreaking discoveries in the p. 10 has since added chief of nephrology, vasculature of tumors; the pregnancy cancer scientist, and, most recently, disorder, preeclampsia; and the chief academic offi cer at Beth Israel side effects of cholesterol-lowering Deaconess Medical Center to drugs, just to name a few. “I’d his wide-ranging resume. “Over the like to think that some of the best years, I have always been interested solutions to problems have come in how cells multiply and spread and from people who traditionally have the general problem of cancer,” not been educated in that discipline he muses. “But along the way there but who bring in something from has been, I would say, more than somewhere else,” says Sukhatme. one signifi cant detour, making me “It could be a technology, it could a bit of a jack of all trades and be a way of thinking, it could be Repair of perhaps not a master of any one.” anything, but it’s that crossing of Genetic Wear and Tear CONTINUED ON P. -

A Crítica De Murilo Mendes Em Cartas Para Guilhermino Cesar

RODOLFO, Luciano e REBELLO, Lúcia Sá. A crítica de Murilo Mendes em Cartas para Guilhermino Cesar. Revista FronteiraZ, São Paulo, n. 8, julho de 2012. A CRÍTICA DE MURILO MENDES EM CARTAS PARA GUILHERMINO CESAR Luciano Rodolfo Doutorando UFRGS Lúcia Sá Rebello Prof.a Dra. do PPG Letras UFRGS RESUMO: Neste artigo analisamos alguns trechos da correspondência inédita de Murilo Mendes (1901 – 1975) enviada a Guilhermino Cesar (1908 – 1993) no final dos anos 1920. São postos em relevo alguns temas recorrentes nas missivas, sobretudo aqueles que tratam do cotidiano do poeta mineiro no estado do Rio de Janeiro, bem como as críticas substantivas, incipientes e quase que despretensiosas que Murilo propunha em suas cartas seja sobre os textos que Guilhermino Cesar lhe enviava, seja sobre a obra de coetâneos seus como, por exemplo, Mário de Andrade (1893 – 1945). PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Murilo Mendes, cartas, crítica ABSTRACT: In this article we analyze fragments from some Murilo Mendes (1901 – 1975)’ unpublished letters, which were sent to Guilhermino Cesar (1908 – 1993) in the late 1920s. Some recurring themes are pointed out in those letters, especially those dealing with the daily routine of that poet from Minas Gerais in the State of Rio de Janeiro. We expose, as well, the substantial, incipient and almost unpretentious criticism proposed by Murilo in his letters, either about the texts sent by Guilhermino Cesar to him, or about the work of his countrymen, for instance, Mario de Andrade’s (1893 – 1945) work. KEY WORDS: Murilo Mendes, letters, criticism 1 RODOLFO, Luciano e REBELLO, Lúcia Sá. A crítica de Murilo Mendes em Cartas para Guilhermino Cesar. -

MUJERES INTELECTUALES Feminismos Y Liberación En América Latina Y El Caribe

Pensamientos silenciados Colección Antologías del Pensamiento Social Latinoamericano y Caribeño MUJERES INTELECTUALES Feminismos y liberación en América Latina y el Caribe Alejandra de Santiago Guzmán Edith Caballero Borja Gabriela González Ortuño AA.VV. MUJERES INTELECTUALES Mujeres intelectuales : feminismos y liberación en América Latina y el Caribe / Mirna Paiz Cárcamo ... [et al.] ; compilado por Alejandra de Santiago Guzmán ; Edith Caballero ; Gabriela González Ortuño. - 1a ed . - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : CLACSO, 2017. Libro digital, PDF - (Antologías del pensamiento social latinoamericano y caribeño / Gentili, Pablo) Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-722-247-0 1. Mujeres. 2. Intelectuales. 3. Feminismo. I. Paiz Cárcamo, Mirna II. de San- tiago Guzmán, Alejandra, comp. III. Caballero, Edith, comp. IV. González Ortuño, Gabriela, comp. CDD 305.42 Otros descriptores asignados por CLACSO: Feminismo / Mujeres Negras / Mujeres Indígenas / Mujeres Intelectuales / Derechos Humanos / Discriminación / Cultura / Pensamiento Decolonial / Pensamiento Crítico / América Latina Colección Antologías del Pensamiento Social Latinoamericano y Caribeño Serie Pensamientos Silenciados MUJERES INTELECTUALES FEMINISMOS Y LIBERACIÓN EN AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE Alejandra de Santiago Guzmán Edith Caballero Borja Gabriela González Ortuño (Editoras) Mirna Paiz Cárcamo Madres de Plaza de Mayo Violet Eudine Barriteau Betty Ruth Lozano Lerma Julieta Paredes Moira Millán Ochy Curiel Martha Teresita de Barbieri Natalia Quiroga Díaz Ivone