Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Sveshnikov-Mental Imagery in Prayer

Mental Imagery in Eastern Orthodox Private Devotion by Father Sergei Sveshnikov Just as there can be a properly trained voice, there can be a properly trained soul.[1] —Fr. Alexander Yelchaninov This presentation is based on the research that I undertook for a book titled Imagine That… : Mental Imagery in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Private Devotion, published in paperback in February of 2009 with the blessing of His Eminence Archbishop Kyrill of San Francisco. The work is an analytical comparison of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox attitudes toward mental imagery. In this presentation, I wish to focus specifically on the Orthodox tradition of prayer. * * * Eastern Orthodoxy displays a great degree of uniformity in following a path of stillness of thought and silence of mind to achieve the prayer of heart in private devotion. Saint John Climacus writes in The Ladder (28:19) that “the beginning of prayer consists in chasing away invading thoughts…” (285) The mind is to be freed from all thoughts and images and focused on the words of prayer. Further in the chapter on prayer (28), St. John instructs not to accept any sensual images during prayer, lest the mind falls into insanity (42; 289); and not to gaze upon even necessary and spiritual things (59; 292). Unlike some forms of Roman Catholic spirituality, the Orthodox Tradition does not encourage the use of mental imagery. In fact, it almost appears to forbid sensory imagination during prayer altogether. In the words of one of the contemporary Orthodox elders, Abbot Nikon (Vorobyev) (1894-1963), “that, which sternly, decisively, with threats and imploring is forbidden by the Eastern Fathers—Western ascetics strive to acquire through all efforts and means” (424). -

GLIMPSES INTO the KNOWLEDGE, ROLE, and USE of CHURCH FATHERS in RUS' and RUSSIAN MONASTICISM, LATE 11T H to EARLY 16 T H CENTURIES

ROUND UP THE USUALS AND A FEW OTHERS: GLIMPSES INTO THE KNOWLEDGE, ROLE, AND USE OF CHURCH FATHERS IN RUS' AND RUSSIAN MONASTICISM, LATE 11t h TO EARLY 16 t h CENTURIES David M. Goldfrank This essay originated at the time that ASEC was in its early stages and in response to a requestthat I write something aboutthe church Fathers in medieval Rus'. I already knew finding the patrology concerning just the original Greek and Syriac texts is nothing short of a researcher’s black hole. Given all the complexities in volved in the manuscript traditions associated with such superstar names as Basil of Caesarea, Ephrem the Syrian, John Chrysostom, and Macarius of wherever (no kidding), to name a few1 and all of The author would like to thank the staffs of the Hilandar Research Library at The Ohio State University and, of course, the monks of Hilandar Monastery for encouraging the microfilming of the Hilandar Slavic manuscripts by Ohio State. I thank the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; and Georgetown University’s Woodstock Theological Library as well as its Lauinger Library Reference Room for their kind help. Georgetown University’s Office of the Provost and Center for Eurasian, East European and Russian Studies provided summer research support. Thanks also to Jennifer Spock and Donald Ostrowski for their wise suggestions. 1 An excellent example of this is Plested, Macarian Legacy. For the spe cific problem of Pseudo-Macarius/Pseudo-Pseudo-Macarius as it relates to this essay, see NSAW, 78-79. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

Bulgakov Handbook

October 21 G.† Our Ven. Father Hilarion the Great He was born in Palestine, near Gaza City, studied the sciences and was baptized in Alexandria. When he was 15 years old, Hilarion heard about Ven. Anthony the Great and admiring "Anthony's spiritually divine, virtuous way of life" went to him. Having returned home with a blessing from Ven. Anthony, Hilarion found that his parents died and, "despising all worldly pleasures", distributed all his remaining inherited estate to the poor and in a certain deserted place was devoted entirely to prayer and abstinence. St. Hilarion struggled a lot with unclean thoughts, who confused his mind and inflamed his body; but he exhausted his body with work and drove away these thoughts by prayer and meditation on God. The holy hermit suffered much from demons and more than once while standing in prayer heard the crying of children, sobbing of women, roaring of lions and other wild animals, awful noises and confusion presented by the demons. But he did not fear the "demonic traps" and through fervent prayer conquered the "gloomy enemy powers". Once, robbers set upon the holy ascetic, but he by the power of his word convinced them to leave their vice and to lead a good life. Soon all of Palestine heard about the holy hermit's life and many began to come to him for healing of body and soul, but others wished to save their soul under his direction. With his blessing many monasteries were built in Palestine, and going from one monastery to another, he established a strict ascetic paradigm of life in them, having become the same kind of trainer for those seeking salvation in Palestine as Ven. -

The Image of Justinianic Orthopraxy in Eastern Monastic Literature

The Image of Justinianic Orthopraxy in Eastern Monastic Literature 2 From 535 to 546, the emperor Justinian issued a series of imperial constitutions which sought to regulate the activities of monks and monasteries. Unprecedented in its scope, this legislative programme marked an attempt by the emperor to bring ascetics firmly under the purview of his government. Taken together, its rulings legislated on virtually every aspect of the ascetic life, prescribing a detailed model of ‘orthopraxy,’ or correct behaviour, to which the emperor demanded monks adhere. However, whilst it is clichéd to evoke Justinian’s status as a reformer of the law, scholars continue to view these orthopraxic rulings with some uncertainty. This is a reflection, in part, of the difficulties faced when attempting to judge the extent to which they were ever adopted or enforced. Studies of the emperor’s divisive religious policies have tended to focus instead upon matters of doctrine and, in particular, Justinian’s efforts to enforce his view of orthodoxy upon anti-Chalcedonian, monastic dissidents. This paper builds upon recent work to argue that the effects of Justinian’s monastic legislation were, in fact, widely felt.1 It will argue that accounts of the mid-sixth century by Eastern monastic authors reveal widespread familiarity with the rulings on ascetic practice contained in the emperor’s Novels. Their reception reveals the extent of imperial power over ascetics during this period, frequently presented as one in which the ‘holy man’ exercised almost boundless social and spiritual authority. I will concentrate on three main examples to illustrate this point, chosen to represent a suitable cross-section of the contemporary monastic movement: Cyril of Scythopolis’ Life of Sabas, the Life of Z‘ura in the Lives of the Eastern Saints by John of Ephesus, and the Coptic texts which detail the career of the Egyptian monastic leader, Abraham of Farshut.2 ORTHOPRAXY IN JUSTINIAN’S MONASTIC LEGISLATION Firstly, however, we must discuss Justinian’s monastic laws in greater detail. -

The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St

HOLY PSALMODY OF Kiahk According to the orders of the Coptic Orthodox Church First Edition }"almwdi8a Ecouab 8nte pi8abot ak <oi 8M8vrh+ 8etaucass 8nje nenio+ 8n+ek8klhsi8a 8nrem8n<hmi M St. George & St. Joseph Coptic Orthodox Church K The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St. George and St Joseph Church Montreal, Canada Kiahk 1724 A. M., December 2007 A. D. St George & St Joseph Church 17400 Boul. Pierrefonds Pierrefonds, QC. CANADA H9J 2V6 Tel.: (514) 626‐6614, Fax.: (514) 624‐8755 http://www.stgeorgestjoseph.ca Behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is His Name. Luke 1: 48 - 49 Hhppe gar isjen +nou senaermakarizin 8mmoi 8nje nigene8a throu@ je afiri nhi 8nxanmecnis+ 8nje vh etjor ouox 8fouab 8nje pefran. His Holiness Pope Shenouda III Pope of Alexandria, and Patriarch of the see of saint Mark Peniwt ettahout 8nar,hepiskopos Papa abba 0enou+ nimax somt Preface We thank the Lord, our God and Saviour, for helping us to start this project. In this first edition, our goal was to gather pre‐translated hymns, and combine them with Midnight Praises in one book. God willing, our final goal is to have one book where the congregation can follow all the proceedings without having to refer to numerous other sources. We ask and pray to our Lord to help us complete this project in the near future. The translated material in this book was collected from numerous sources: Coptichymns.net web site Kiahk Praises, by St George & St Shenouda Church The Psalmody of Advent, by William A. -

Shenoute Paper Draft

Mimetic Devotion and Dress in Some Monastic Portraits from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit* Thelma K. Thomas For the monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit in Middle Egypt there is good archaeological documentation, a wealth of primary written sources mainly in the form of inscriptions, and a long history of scholarship illuminating both the site and the paintings at the center of this study.1 The archaeological site (figure 1) is extensive, and densely built. The many paintings, usually dated to the sixth and seventh centuries, survive in varying states of preservation from a range of functional contexts, however in this discussion I focus on * I am grateful to Hany Takla for inviting me to present a version of this article at the Twelfth St. Shenouda-UCLA Conference of Coptic Studies in July 2010. I owe thanks as well to Jenn Ball, Betsy Bolman, Jennifer Buoncuore, Mariachiara Giorda, Tom Mathews, and Maged Mikhail. Many of the issues considered here will be addressed more extensively in a book-length study, Dressing Souls, Making Monks: Monastic Habits of the Desert Fathers. 1 The main archaeological publications include: Jean Clédat, Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouit, Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. 12 (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, 1904); Jean Clédat, Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouit, Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. 39 (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1916); Jean Maspéro, “Fouilles executées à Baouit, Notes mises en ordre et éditées par Etienne Drioton,” Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. -

Asceticism: a Missing Dimension in Climate Change Responses Ann R

Asceticism: a Missing Dimension in Climate Change Responses Ann R. Woods For the Pacific Coast Theological Society, Fall 2016 Meeting [A]ll of us are deeply frustrated with the stubborn resistance and reluctant advancement of earth-friendly politics and practices. Permit us to propose that the reason for this hesitation and hindrance may lie in the fact that we are unwilling to accept personal responsibility and demonstrate personal sacrifice. In the Orthodox Christian tradition we refer to this “missing dimension” as ascesis, which could be translated as abstinence and moderation, or – better still – simplicity and frugality…. This may be a fundamental religious and spiritual value. Yet it is also a fundamental ethical and existential principle. -- Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I 1 In the face of an ever-worsening climate change crisis, one significant concern is the need for lifestyle changes that reduce human impact on the natural world.2 Environmentalists have been advocating for these changes to become more substantial in several ways – for more people to embrace change, for the changes to be more significant, and for change to happen more rapidly. However, distractions, temptations, competing values, discouragement, and denial combine to minimize change just when maximization is needed. As Pope Francis says in Laudato Si’, “Regrettably, many efforts to seek concrete solutions to the environmental crisis have proved ineffective, not only because of powerful opposition but also because of a more general lack of interest. Obstructionist attitudes, even on the part of believers, can range from denial of the problem to indifference, nonchalant resignation or blind confidence in technical solutions. -

The Forerunner

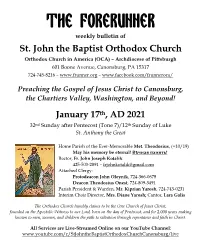

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

ABSTRACT the Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories Of

ABSTRACT The Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret Scott A. Rushing, Ph.D. Mentor: Daniel H. Williams, Ph.D. This dissertation analyzes the transposition of the apostolic tradition in the fifth-century ecclesiastical histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. In the early patristic era, the apostolic tradition was defined as the transmission of the apostles’ teachings through the forms of Scripture, the rule of faith, and episcopal succession. Early Christians, e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen, believed that these channels preserved the original apostolic doctrines, and that the Church had faithfully handed them to successive generations. The Greek historians located the quintessence of the apostolic tradition through these traditional channels. However, the content of the tradition became transposed as a result of three historical movements during the fourth century: (1) Constantine inaugurated an era of Christian emperors, (2) the Council of Nicaea promulgated a creed in 325 A.D., and (3) monasticism emerged as a counter-cultural movement. Due to the confluence of these sweeping historical developments, the historians assumed the Nicene creed, the monastics, and Christian emperors into their taxonomy of the apostolic tradition. For reasons that crystallize long after Nicaea, the historians concluded that pro-Nicene theology epitomized the apostolic message. They accepted the introduction of new vocabulary, e.g. homoousios, as the standard of orthodoxy. In addition, the historians commended the pro- Nicene monastics and emperors as orthodox exemplars responsible for defending the apostolic tradition against the attacks of heretical enemies. The second chapter of this dissertation surveys the development of the apostolic tradition.