A New Vision for Saskatchewan's Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canwest Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies

Wednesday, September 30, 2009 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan TheStarPhoenix.com D1 New Top 100 list showcases Sask.’s diversification By Katie Boyce almost $3 billion since 2007. Viterra Inc., in its second year of his year’s Top 100 Saskatchewan operation, has also experienced significant Companies list is filled with sur- growth in revenue, jumping by almost T prises. $3 billion in the last year to claim third Besides a new company in the No. 1 spot, ranking. Long-standing leaders Canpotex 23 businesses are featured for the first time Limited and Cameco Corporation continue in the 2009 ranking, which is based on 2008 to make the top five, backed by the profit- gross revenues and sales. The additions able potash market. — headquartered in Carlyle, Davidson, Este- One major modification to this year’s list van, Lampman, Melfort, Regina, Rosetown, has been to exclude the province’s individual Saskatoon, Warman, and Yorkton — show retail co-operatives, instead allowing Feder- off the incredible economic growth that our ated Co-operatives Ltd. to represent these province has experienced during the last year. businesses. Another change has been in how 1 Covering a wide cross-section of industries SaskEnergy reports its revenue. Rather than in our province, newcomers to the list include providing gross revenue amounts, the crown PotashCorp Allan Construction, Kelsey Group of Compa- corporation started this fiscal year to report nies, Partner Technologies Incorporated and only net revenue, which accounts for the Reho Holding Ltd. (owner of several Warman significant drop in rankings. companies) in the manufacturing and con- The Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies is struction field, and Arch Transco Ltd. -

2015-2016 Annual Report

2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Association Profile………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 01 Our Vision………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 01 Our Mission………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 01 Strategic Priorities (2015-2016)…………………………………………………………………………………………..01 ACEC-SK Code of Consulting Practice……………………………………………………………………………….………….....02 2015-2016 ACEC-SK Board of Directors………………………………………………………………...…………….…………03 Chair’s Report…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 Executive Director’s Report……………………………………………………………………………...…………………………....06 2014 – 2015 ACEC-SK Annual General Meeting Minutes………………………………………………………………….08 Buildings (Regina & Saskatoon) Committee Report..………………………………………………………………………..14 Communications Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………...………………..15 Environment/Water Resources Committee Report…………………………………………………………………………..16 Human Resources Committee Report………………………………………………………………………………………………17 Industry/Resources Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………………19 Risk Mitigation Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………….…….…….21 Transportation Committee Report…………………………………………………………………..….……………………………22 ACEC-Canada Liaison Report……………………………………………………………………………………………………………23 Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists (APEGS) Liaison Report………………………………25 Women in Consulting Committee Report………………………………………………………………………………………….27 Young Professionals Group Liaison Report…………………………………………………….…………………….…………....28 Associate Member -

Saskatchewan Party Plan - Four Year Detailed Costing

Securing the Future NEW IDEAS FOR SASKATCHEWAN Brad Wall Authorized by the Chief Official Agent for the Saskatchewan Party Leader A Message from Brad Wall askatchewan is a great province with Stremendous potential for the future. But ask yourself this question: Are we really going to achieve our potential under this tired, old NDP government? OR, is it time for a new government with new ideas to grow our economy, keep our young people in Saskatchewan, fix our ailing health care system and make sure Saskatchewan takes its place as a leader in Canada? For too long, the NDP has squandered Saskatchewan’s tremendous potential and recorded the longest hospital waiting lists, crumbling highways, the highest crime rates, the largest population loss and the worst job creation record in the country. The Saskatchewan Party has a team of men and women with new ideas to help our province achieve its potential and secure a bright future for Saskatchewan and its people. Thank you for reading our platform and the Saskatchewan Party’s new ideas for securing Saskatchewan’s future. Securing the Future Table of Contents Click on chapter title to jump directly to each section. Page 3 New Ideas to Keep Young People in Saskatchewan Page 7 Writing a Prescription for Better Health Care Page 12 New Ideas for Families Page 16 New Ideas for Jobs and Economic Growth Page 23 Building Pride in Saskatchewan Page 28 Publicly Owned Crowns that Work for Saskatchewan Page 31 Making our Communities Safer Page 35 New Ideas to Help Saskatchewan Go Green Page 39 More Accountable Government Page 43 Four Year Fiscal Forecast Page 44 Saskatchewan Party Plan - Four Year Detailed Costing Page 45 Fiscal Sustainability - Opinion from the Centre for Spatial Economics 3 Securing the Future New Ideas to Keep Young People in Saskatchewan Rebating up to $20,000 in post-secondary tuition for graduates who stay in Saskatchewan for seven years. -

Saskatchewan Provincial Budget 2012-13 Budget Summary

The Honourable Ken Krawetz Deputy Premier Minister of Finance SASKATCHEWAN PROVINCIAL BUDGET 12-13 KEEPING THE SASKATCHEWAN ADVANTAGE BUDGET SUMMARY MiniSter’S MeSSage I’m pleased to table the 2012-13 Budget and supporting documents for public discussion and review. Over the past few years, Saskatchewan people have helped to create the “Saskatchewan Advantage,” a combination of balanced budgets, reduced debt and lower taxes, a strong and growing economy and the tremendous quality of life we all enjoy. Our province is now the best place in Canada to live, work, start a business, receive an education, raise a family and build a life. Saskatchewan has become a magnet for people across the country and around the world, recording the largest population growth in any census period since Statistics Canada started doing the census every five years in 1956. People are coming here because they recognize that Saskatchewan is now a place of opportunity. Keeping the SaSKatchewan advantage The 2012-13 Budget is all about “Keeping the Saskatchewan Advantage.” While other jurisdictions post deficits, Saskatchewan will once again balance its budget. While other provinces struggle with sluggish growth, Saskatchewan is projected to lead the nation in economic growth. Even in a time of global uncertainty, our government’s focus will remain squarely on enhancing and preserving Saskatchewan’s quality of life through prudent fiscal management. This year’s budget also strives to make life more affordable and provide better access to health care. This budget provides for enhancements to the Active Families Benefit, as well as for the introduction of a Saskatchewan Advantage scholarship and a Saskatchewan Advantage grant for education savings. -

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report Unit 1E Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change Project H. Diaz, M. Hurlbert, J. Warren and D. R. Corkal October 2009 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations ………………………………………………………. 3 I Introduction ………………………………………………………… 5 II Methodology .……………………………………………………….. 5 III Integrative Discussion ……………………………………………… 9 IV Conclusions .………………………………………………………… 54 V References ………………………………………………………….. 60 VI Appendices …………………………………………………………. Appendix 1 - Organizational Overviews ..………………………… 62 Introduction ……………………………………………………… 62 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ...……..………………….… 63 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment …..………………….… 76 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .………………………… 85 SaskWater …………………………………….…………………. 94 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration……………………… 103 Appendix 2 - Interview Summaries ……………………….……… 115 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ……………………….……. 116 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment ….…………………….. 154 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .…………………….…… 182 SaskWater ………………………………………………….……. 194 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration …………………….. 210 Irrigation Proponents ……………………………………………. 239 Watershed Advisory Groups ……………………………………. 258 Environment Canada …………………………………………….. 291 SRC ..…………………………………………………………… 298 PPWB …………………………………………………………… 305 Focus Group …………………………………………………….. 308 Appendix 3 - Field Work Guide …………………………………. 318 2 Abbreviations AAFC – Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ADD Boards – Agriculture Development and Diversification Boards AEGP - Agri-Environmental -

Saskatchewan's Growth Plan

VISION 2020 AND BEYOND Opening Message Too often enterprise-oriented governments appear to seek growth for the sake of growth. This is a mistake – one that can cause governments to lose focus and discipline. The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth is about that focus and discipline. It sets out the Government of Saskatchewan’s vision for a province of 1.2 million people by 2020. It is a plan for economic growth that builds on the strength of Saskatchewan’s people, resources and innovation to sustain Saskatchewan’s place among Canada’s economic leaders. Growth will be a result of continued investments in a competitive economy, infrastructure and a skilled workforce. Building on our agricultural and natural resource advantage, Saskatchewan will be a global leader in export and trade by 2020 and will invest in knowledge and innovation in the development of Saskatchewan’s future economy. Capital investments in new projects and expansions will grow our economy, and Saskatchewan will continue to welcome newcomers from across Canada and throughout the world to live and work in our province. An expanding economy is the foundation for a growing and prosperous province. The purpose of growth is to build a better quality of life for all Saskatchewan residents. To this end, the Saskatchewan Plan for Growth outlines the government’s direction to improve health care and education outcomes, while building growing and safe communities and improving the lives of persons with disabilities in Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth reaffirms the provincial government’s commitment to fiscal responsibility through balanced budgets and further reduction in government debt. -

Budget and Performance Plan Summary Minister of Finance Minister’S Message

2004 –2005 Saskatchewan Provincial Budget The Hon. Harry Van Mulligen Budget and Performance Plan Summary Minister of Finance Minister’s Message I am pleased to table the 2004-05 Budget and supporting documents for public review and discussion. This document provides more than just budget numbers. It includes comprehensive reports on both our fiscal and economic outlook, which forms the context and foundation for the 2004-05 Budget. I would like to point out two sections that are particularly relevant in this year’s Budget. First, a technical paper that discusses federal transfers, one of our most challenging issues. Secondly, a section that examines health care funding. Health care represents our most rapidly growing expenditure area. This section of the report outlines how this money is being spent and the ongoing funding needs required to maintain the current health system. I also encourage you to review the government-wide performance plan summary that sets out the broad vision and goals for government departments. Individual plans, with detailed goals and objectives, are also available on each department’s website. These performance plans are one further step in our ongoing commitment to improving accountability of this Government to the people of Saskatchewan. It is my hope that the material found in these documents will help create a solid understanding of our economy, our finances, and Saskatchewan’s future. Harry Van Mulligen Minister of Finance Table of Contents INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Performance Plan Summary . 4 TECHNICAL PAPERS Health Care Spending in Saskatchewan . 20 Equalization . 26 Saskatchewan’s Economic Outlook . 32 Saskatchewan’s GRF Financial Outlook . -

Hansard: April 01, 2005

FIRST SESSION - TWENTY-FIFTH LEGISLATURE of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan ____________ DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS ____________ (HANSARD) Published under the authority of The Honourable P. Myron Kowalsky Speaker N.S. VOL. XLVII NO. 83A FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 2005, 10 a.m. MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN Speaker — Hon. P. Myron Kowalsky Premier — Hon. Lorne Calvert Leader of the Opposition — Brad Wall Name of Member Political Affiliation Constituency Addley, Graham NDP Saskatoon Sutherland Allchurch, Denis SP Rosthern-Shellbrook Atkinson, Hon. Pat NDP Saskatoon Nutana Bakken, Brenda SP Weyburn-Big Muddy Beatty, Hon. Joan NDP Cumberland Belanger, Hon. Buckley NDP Athabasca Bjornerud, Bob SP Melville-Saltcoats Borgerson, Lon NDP Saskatchewan Rivers Brkich, Greg SP Arm River-Watrous Calvert, Hon. Lorne NDP Saskatoon Riversdale Cheveldayoff, Ken SP Saskatoon Silver Springs Chisholm, Michael SP Cut Knife-Turtleford Cline, Hon. Eric NDP Saskatoon Massey Place Crofford, Hon. Joanne NDP Regina Rosemont D’Autremont, Dan SP Cannington Dearborn, Jason SP Kindersley Draude, June SP Kelvington-Wadena Eagles, Doreen SP Estevan Elhard, Wayne SP Cypress Hills Forbes, Hon. David NDP Saskatoon Centre Gantefoer, Rod SP Melfort Hagel, Glenn NDP Moose Jaw North Hamilton, Doreen NDP Regina Wascana Plains Harpauer, Donna SP Humboldt Harper, Ron NDP Regina Northeast Hart, Glen SP Last Mountain-Touchwood Heppner, Ben SP Martensville Hermanson, Elwin SP Rosetown-Elrose Higgins, Hon. Deb NDP Moose Jaw Wakamow Huyghebaert, Yogi SP Wood River Iwanchuk, Andy NDP Saskatoon Fairview Junor, Judy NDP Saskatoon Eastview Kerpan, Allan SP Carrot River Valley Kirsch, Delbert SP Batoche Kowalsky, Hon. P. Myron NDP Prince Albert Carlton Krawetz, Ken SP Canora-Pelly Lautermilch, Eldon NDP Prince Albert Northcote McCall, Warren NDP Regina Elphinstone-Centre McMorris, Don SP Indian Head-Milestone Merriman, Ted SP Saskatoon Northwest Morgan, Don SP Saskatoon Southeast Morin, Sandra NDP Regina Walsh Acres Nilson, Hon. -

Hansard April 20, 2000

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN 837 April 20, 2000 The Assembly met at 10 a.m. government. Prayers The people that have signed this petition are from Naicam and ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS Lintlaw. PRESENTING PETITIONS Mr. Gantefoer: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. I too rise on behalf of citizens concerned about the high price of fuel. The Mr. Elhard: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. I rise this morning to prayer reads as follows: present a petition opposed to the private sales exemption of $3,000 on the purchase of used vehicles. And the prayer reads as follows: Wherefore your petitioners humbly pray that your Hon. Assembly may be pleased to cause the federal and Wherefore your petitioners humbly pray that your Hon. provincial governments to immediately reduce fuel taxes Assembly may be pleased to cause the government to provide by 10 cents a litre, cost shared by both levels of a $3,000 exemption for dealers in addition to private sales, government. therefore providing a fair tax break to the consumers of this province wherever they choose to purchase a vehicle. Signatures on this petition, Mr. Speaker, are mostly from the community of Melfort, but also from Brooksby and Kinistino. And as in duty bound, your petitioners will ever pray. I so present. And this petition is signed by citizens in such diverse communities as Esterhazy, Melville, Yorkton, Moosomin, Kelvington, and Mr. Toth: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. As well I rise to present Ebenezer. a petition. This one deals with the tax on used vehicles. Reading the prayer: Mr. Heppner: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. -

Moving Saskatchewan Forward

Growth and Opportunity Brad Wall and the Brad Wall Moving Saskatchewan Forward 2 Table of Contents Message from Premier Brad Wall 3 New Ideas to Keep Saskatchewan Moving Forward 4 Growth and Opportunity 6 Today and Tomorrow in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Party Plan: Moving Forward Through Growth and Opportunity Saskatchewan Party Record: A Strong Economy, A Growing Province Affordability 16 Today and Tomorrow in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Party Plan: Moving Forward on Affordability Saskatchewan Party Record: Lowering Taxes to Make Life More Affordable Quality of Life 22 Today and Tomorrow in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Party Plan: Improving Quality of Life Moving Forward Saskatchewan Party Record: Improved Services, A Better Quality of Life Responsive and Responsible Government 36 Today and Tomorrow in Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Party Plan: Moving Forward With Responsive and Responsible Government Saskatchewan Party Record: Responsive, Trustworthy, Accountable Platform Costing 46 1 Message from Premier Brad Wall Saskatchewan is Moving Forward Over the past four years, your Saskatchewan Party government has pursued a growth agenda – but growth is not the end goal. Our goal is to ensure that all Saskatchewan people share in the benefits of growth, to secure our province’s future, and to improve the quality of life of everyone in our province. Today in Saskatchewan, more people than ever are calling our province home, and we have the lowest unemployment rate in the country. Today in Saskatchewan, our economy is leading the nation, and is predicted to lead the nation again next year. Over the last four years, 24,500 new jobs have been created. Today in Saskatchewan, surgical wait lists are getting shorter. -

Ccall Regina Elphinstone-Centre

STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES Hansard Verbatim Report No. 25 – October 6, 2005 Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Twenty-fifth Legislature STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES 2005 Mr. Graham Addley, Chair Saskatoon Sutherland Mr. Dan D’Autremont, Deputy Chair Cannington Ms. Doreen Eagles Estevan Mr. Andy Iwanchuk Saskatoon Fairview Mr. Allan Kerpan Carrot River Valley Mr. Warren McCall Regina Elphinstone-Centre Hon. Mark Wartman Regina Qu’Appelle Valley Published under the authority of The Honourable P. Myron Kowalsky, Speaker STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES 493 October 6, 2005 [The committee met at 10:00.] with legislation governing its activities related to financial reporting, safeguarding public resources, revenue raising, The Chair: — Good morning and I’ll call to order the Standing spending, borrowing, and investing. Therefore we have no Committee on Crown and Central Agencies. Some recommendations on these matters that require the attention of administrative issues, just to remind members that the this committee. committee meeting is being webcast and is available for in-house TV viewing. Following today’s meeting, the full In carrying out our work we worked together with the appointed meeting will be video streamed on the Internet and will be on auditors, Meyers Norris Penny, and we received excellent the Legislative Assembly committee website. And the co-operation from both Meyers Norris Penny and also the television rebroadcast for the public will occur in November, management of SaskWater. and I’m sure we’ll all be waiting for that. Mr. Drayton: — Thank you, Mr. Chair. My comments would Today’s agenda is reviewing the SaskWater 2004 annual report also be brief. -

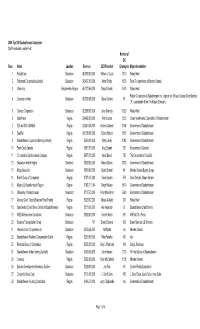

2009 Top 100 List

2009 Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies StarPhoenix and Leader-Post Number of SK Rank Name Location Revenue CEO/President Employees Major shareholders 1 PotashCorp Saskatoon $9,898,000,000 William J. Doyle 1810 Widely Held 2 Federated Co-operatives Limited Saskatoon $8,400,368,000 Arthur Postle 1500 Retail Co-operatives in Western Canada 3 Viterra Inc. Registered in Regina $6,777,566,000 Mayo Schmidt 1600 Widely Held Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc., Agrium Inc., Mosaic Canada Crop Nutrition, 4Canpotex Limited Saskatoon $5,200,000,000 Steve Dechka 63 LP., a subsidiary of the The Mosaic Company 5 Cameco Corporation Saskatoon $2,859,000,000 Jerry Grandey 1820 Widely Held 6 SaskPower Regina $1,489,000,000 Pat Youzwa 2500 Crown Investments Corporation of Saskatchewan 7 SGI and SGI CANADA Regina $1,241,684,000 Andrew Cartmell 1894 Government of Saskatchewan 8 SaskTel Regina $1,138,000,000 Robert Watson 5063 Government of Saskatchewan 9 Saskatchewan Liquor and Gaming Authority Regina $960,980,000 Barry Lacey 1085 Government of Saskatchewan 10 Farm Credit Canada Regina $951,700,000 Greg Stewart 760 Government of Canada 11 Co-operators Life Insurance Company Regina $857,700,000 Kevin Daniel 720 The Co-operators Group Ltd. 12 Saskatoon Health Region Saskatoon $808,000,000 Maura Davies 12000 Government of Saskatchewan 13 Mega Group Inc. Saskatoon $800,000,000 Benoit Simard 48 Member Owned Buying Group 14 Brandt Group of Companies Regina $797,467,000 Gavin Semple 575 Gavin Semple, Shaun Semple 15 Regina Qu'Appelle Health Region Regina $742,717,194 Dwight Nelson 9500 Government of Saskatchewan 16 University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon $710,572,000 Peter MacKinnon 6923 Government of Saskatchewan 17 Alliance Grain Traders/Saskcan Pulse Trading Regina $328,672,293 Murad Al-Katib 240 Widely Held 18 SaskCentral (Credit Union Central of Saskatchewan) Regina $317,860,000 Ken Anderson 97 Saskatchewan Credit Unions 19 AREVA Resources Canada Inc.