Perspectives on Pilgrimage to Folk Deities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Superintending Engineer (O&M) JODHPUR DISCOM

Office of the Superintending Engineer (O&M) JODHPUR DISCOM, JAISALMER-345001 Email ID:[email protected] Phone No: 02992-250466: Fax No:02992-250543 TENDER SPECIFICATION SPECIFICATION No.JdVVNL/ SE/ O&M/ JSM/TN-09 or Operation & Maintenance of 33/11 KV Sub-Stations identified, in respect of various sub-divisions/divisions of SE (O&M), Jodhpur Discom, Jaisalmer VOLUME - I Last date for submission of Bid Proposal is 21.03.2018 up to 02:00PM Cost of tender specification: Rs.2950/- Contact Details Contact Person Superintending Engineer (O&M), Jaisalmer Telephone: +91-2992-250466, +91-9413359847 :Fax +91-2992-250543 :Email [email protected], [email protected] GENERAL PARTICULARS ABOUT THE TENDER IN BRIEF 1 | P a g e JODHPUR VIDYUT VITARAN NIGAM LIMITED Office of the Superintending Engineer (O&M) Jodhpur Discom,Jaisalmer Email ID:- [email protected]. No.02992-250466/ Fax No.- 02992-250543 JDVVNL/SE/O&M/JSM/F/TN-09/2017-18 D………………..Dt………………………. SPECIFICATION No.JdVVNL/ SE/ O&M/ JSM/TN-09 for Operation & Maintenance of 33/11 KV Sub-Stations identified, in respect of Pokran,Nachana sub-divisions under Pokran Division of Jaisalmer circle under the domain of Jodhpur discom i.e. SE(O&M) JdVVNL, Jaisalmer Availability of tender documents on 19.02.2018 (tentative) website Start Date & Time for online 19.02.2018 submission of Tender bids Last Date & Time for down loading of Up to 20.03.2018; 12:00 PM Tender documents Last Date & Time for online 21.03.2018; 02:00 PM submission of Tender bids Date & Time for online opening of 21.03.2018; 04:00 PM Tender bids Re.1, 180/- (Rs. -

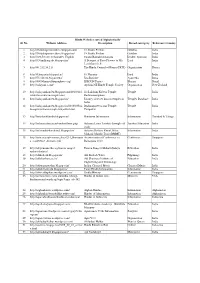

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Ancient Civilizations

1 Chapter – 1 Ancient Civilizations Introduction - The study of ancient history is very interesting. Through it we know how the origin and evolution of human civilization, which the cultures prevailed in different times, how different empires rose uplifted and declined how the social and economic system developed and what were their characteristics what was the nature and effect of religion, what literary, scientific and artistic achievements occrued and thease elements influenced human civilization. Since the initial presence of the human community, many civilizations have developed and declined in the world till date. The history of these civilizations is a history of humanity in a way, so the study of these ancient developed civilizations for an advanced social life. Objective - After teaching this lesson you will be able to: Get information about the ancient civilizations of the world. Know the causes of development along the bank of rivers of ancient civilizations. Describe the features of social and political life in ancient civilizations. Mention the achievements of the religious and cultural life of ancient civilizations. Know the reasons for the decline of various civilizations. Meaning of civilization The resources and art skills from which man fulfills all the necessities of his life, are called civilization. I.e. the various activities of the human being that provide opportunities for sustenance and safe living. The word 'civilization' literally means the rules of those discipline or discipline of those human behaviors which lead to collective life in human society. So civilization may be called a social discipline by which man fulfills all his human needs. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Lord in the Temple, Lord in the Tomb: The Hindu Temple and Its Relationship to the Samādhi Shrine Tradition of Jnāneśvar Mahārāj Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4650q3zk Author McLaughlin, Mark Joseph Publication Date 2014 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4650q3zk#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A L I F O R N I A SANTA BARBARA Lord in the Temple, Lord in the Tomb The Hindu Temple and Its Relationship to the Samādhi Shrine Tradition of Jñāneśvar Mahārāj A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Mark Joseph McLaughlin Committee in charge: Professor Barbara A. Holdrege, Chair Professor David Gordon White Professor Juan E. Campo December 2014 The dissertation of Mark Joseph McLaughlin is approved. _____________________________________________ David Gordon White _____________________________________________ Juan E. Campo _____________________________________________ Barbara A. Holdrege, Committee Chair September 2014 Lord in the Temple, Lord in the Tomb The Hindu Temple and Its Relationship to the Samādhi Shrine Tradition of Jñāneśvar Mahārāj Copyright © 2014 by Mark Joseph McLaughlin iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS hetve jgtamev s=sara%Rvsetve| p/wve svRiváana= xMwve gurve nm:£ HI gu; gIta 33 all my love and gratitude to Asha, Oliver, & Lucian iv I first visited the samādhi shrine of Jñāneśvar Mahārāj in the village of Āḷandī during the winter of 2001 at the end of a year-and-a-half stay in India. -

An Ethnographic Exploration of Islamic Revivalism in Pakistan

© 2021 Authors. Center for Study of Religion and Religious Tolerance, Belgrade, Serbia.This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Muhammad Bilal1 Original scientific paper Fatima Jinnah Women University UDC 28:141.336(549.1) Pakistan THE POLITICS OF POPULAR ISLAM: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION OF ISLAMIC REVIVALISM IN PAKISTAN Abstract In the post-9/11 scenario, the rise of the Taliban and their coalition with Al- Qaeda have engendered new discourses about Islam and Pakistan. In this paper, I present a multi-sited ethnography of Bari Imam, a popular Sufi shrine in Paki- stan while re-evaluating certain suppositions, claims and theories about popular Islam in the country. Have militarization, Shariatisation, and resurgence move- ments such as the Taliban been overzealously discussed and presented as the representative imageries of Islam? I also explore the Sufi dynamics of living Islam, which I will suggest continue to shape the lives and practices of the vast major- ity of Pakistani Muslims. The study suggests that general unfamiliarity of people outside the subcontinent with the Sufi attributes of living Islam, together with their lack of knowledge of the varieties of identification, observance and experi- ence of Islam among Pakistanis, limit not only their understanding of the land of Pakistan, but also their perception of its people and their faith (Islam). Keywords: popular Islam, Sufism, extremism, shrine, multi-sited ethnogra- phy, Pakistan Introduction The first decade of the 21st century witnessed a vitally important shift to- wards Islamic revitalization worldwide with Pakistan a flash point of the reforma- tion discourse. -

Integrated Natural and Human Resources Appraisal of Jaisalmer District

CAZRI Publication No. 39 INTEGRATED NATURAL AND HUMAN RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF JAISALMER DISTRICT Edited by P.C. CHATTERJI & AMAL KAR mw:JH9 ICAR CENTRAL ARID ZONE RESEARCH INSTITUTE JODHPUR-342 003 1992 March 1992 CAZRI Publication No. 39 PUBLICA nON COMMITTEE Dr. S. Kathju Chairman Dr. P.C. Pande Member Dr. M.S. Yadav Member Mr. R.K. Abichandani Member Dr. M.S. Khan Member Mr. A. Kar .Member Mr. Gyanchand Member Dr. D.L. Vyas Sr. A.D. Mr. H.C. Pathak Sr. F. & Ac.O. Published by the Director Central Arid 20he Research In.Hitute, Jodhpur-342 003 * Printed by MIs Cheenu Enterprises, Navrang, B-35 Shastri Nagar, Jodhpur-342 003 , at Rajasthan Law Weekly Press, High Court Road, Jodhpur-342 001 Ph. 23023 CONTENTS Page Foreword- iv Preface v A,cknowledgements vi Contributors vii Technical support viii Chapter I Introduction Chapter II Climatic features 5 Chapter III Geological framework 12 Chapter- IV Geomorphology 14 ChapterY Soils and land use capability 26 Chapter VI Vegetation 35 Chapter VII Surface water 42 Chapter Vill Hydrogeological conditions 50 Chapter IX Minetal resources 57 Chapter X Present land use 58 Chapter XI Socio-economic conditions 62 Chapter XII Status of livestock 67 Chapter X III Wild life and rodent pests 73 Chapter XLV Major Land Resources Units: Characteristics and asse%ment 76 Chapter XV Recommendations 87 Appendix I List of villages in Pokaran and laisalmer Tehsils, laisalmer district, alongwith Major Land Resources Units (MLRU) 105 Appendix II List of villages facing scarcity of drinking water in laisalmer district 119 Appendix III New site~ for development of Khadins in Iaisalmer district ]20 Appendix IV Sites for construction of earthen check dams, anicuts and gully control structures in laisalmer district 121 Appendix V Natural resources of Sam Panchayat Samiti 122 CAZRI Publications , . -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Muslim Saints and Hindu Rulers: the Development of Sufi

The Institute of Ismaili Studies “Muslim Saints and Hindu Rulers: The Development of Sufi and Ismaili Mysticism in the Non-Muslim States of India” Dominique-Sila Khan Key words: Sufism, Sufis, Mysticism, Mystics, spiritual authority, taqiyya, South India, religious pluralism, religious integration, patronage. Abstract: This article focuses on the phenomenon of religious acceptance, integration and pluralism in South India by various Hindu and Muslim leaders in the sixteenth century. It looks at examples of rulers of both religions protecting, maintaining and restoring temples, mosques and shrines which were important to the differing religion, instances include the renovation of Muslim shrines and mosques under Hindu leaders in Marwar under the Rathore dynasty. The author also explores the common occurrences of Ismailis having to live under the guise of Sufis or Hindus in order to escape persecution; this was a necessary precaution for the time. Forceful evidence of religious integration lies in the numerous examples of Hindu leaders becoming devotees of Sufi or Muslim saints and vice versa. Although admittedly the number of incidents of Muslim leaders accepting completely the teachings of Hindu saints are rather limited the reasoning for which Sila-Khan discusses. In varying countries and contexts, scholars have studied the historical links that have existed between political power, primarily embodied in kingship, and spiritual authority as represented by mystics and saints affiliated to various religious movements. The role of Sufism in South Asia and the relationships between Muslim rulers and saints has been widely explored1. It has been often remarked that, as a rule, Muslim kings patronised Sufis, regardless of the latter’s attitude towards political power. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Punishment? on the Depiction of Hell in Vīlhojī's Kathā Gyāncarī

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Hell as ”Eternal” Punishment? On the Depiction of Hell in Vīlhojī’s Kathā Gyāncarī Kempe-Weber, Susanne DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/asia-2018-0011 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-159632 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Kempe-Weber, Susanne (2018). Hell as ”Eternal” Punishment? On the Depiction of Hell in Vīlhojī’s Kathā Gyāncarī. Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques, 72(2):339-362. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/asia-2018-0011 ASIA 2018; 72(2): 339–362 Susanne Kempe-Weber* Hell as “Eternal” Punishment? On the Depiction of Hell in Vīlhojī’s Kathā Gyāncarī https://doi.org/10.1515/asia-2018-0011 Abstract: This paper engages with the literature of the Biśnoī Sampradāya, a religious tradition that emerged in the fifteenth century in Rajasthan and traces itself back to the Sant Jāmbhojī. The paper specifically examines a composition of the sixteenth-seventeenth century poet-saint and head of the tradition Vīlhojī.His Kathā Gyāncarī is a unique composition among the corpus of Biśnoi literature with regard to its genre, style and content. The text revolves around the consequences of one’s actions after death, particularly punishment in hell. This paper aims to illustrate that the Kathā Gyāncarī depicts suffering in hell as the eternal conse- quence of committing sins or crimes, which is unique not only for Biśnoī literature, but for Sant literature in general. -

Los Angeles a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomu

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles FIND THE TRUE COUNTRY: DEVOTIONAL MUSIC AND THE SELF IN INDIA’S NATIONAL CULTURE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by VIVEK VIRANI 2016 © Copyright by Vivek Virani 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Find the True Country: Devotional Music and the Self in India’s National Culture by Vivek Virani Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Daniel M. Neuman, Chair For centuries, the songs of devotional poet-saints have been an integral part of Indian religious life. Countless regional traditions of bhajans (devotional songs) have been able to maintain their existence by adapting to serve the contemporary social needs of their participants. This dissertation draws on fieldwork conducted over 2014-2015 with contemporary bhajan performers from many different genres and styles throughout India. It highlights a specific tradition in the Central Indian region of Malwa based on poetry by Kabir and other Sants (anti- establishment poet-saints) performed by lower-caste singers. This tradition was largely unheard- of half a century ago, but is now a major part of Malwa’s cultural life that has facilitated the creation of lower-caste spiritual networks and created a space for those networks to engage in discourse about social issues. Malwa’s bhajan singers have also become part of India’s popular ii religious and musical life as certain performers have attained celebrity status and been recognized at the national level as living bearers of the Sant tradition. This dissertation follows performers and songs from Malwa into new contexts and explores the processes by which performers and audiences in diverse styles and contexts use Sant bhajans to construct understandings of the self.