Los Angeles a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guru: by Various Authors

Divya Darshan Contributors; Publisher Pt Narayan Bhatt Guru Purnima: Hindu Heritage Society ABN 60486249887 Smt Lalita Singh Sanskriti Divas Medley Avenue Liverpool NSW 2170 Issue Pt Jagdish Maharaj Na tu mam shakyase drashtumanenaiv svachakshusha I Divyam dadami te chakshu pashay me yogameshwaram Your external eyes will not be able to comprehend my Divine form. I grant you the Divine Eye to enable you to This issue includes; behold Me in my Divine Yoga. Gita Chapter 11. Guru Mahima Guru Purnima or Sanskriti Diwas Krishnam Vande Jagad Gurum The Guru: by various Authors Message of the Guru Teaching of Raman Maharshi Guru and Disciple Hindu Sects Non Hindu Sects The Greatness of the Guru Prayer of Guru Next Issue Sri Krishna – The Guru of All Gurus VASUDEV SUTAM DEVAM KANSA CHANUR MARDAMAN DEVKI PARAMAANANDAM KRISHANAM VANDE JAGADGURUM I do vandana (glorification) of Lord Krishna, the resplendent son of Vasudev, who killed the great tormentors like Kamsa and Chanoora, who is a source of greatest joy to Devaki, and who is indeed a Jagad Guru (world teacher). 1 | P a g e Guru Mahima Sab Dharti Kagaz Karu, Lekhan Ban Raye Sath Samundra Ki Mas Karu Guru Gun Likha Na Jaye ~ Kabir This beautiful doha (couplet) is by the great saint Kabir. The meaning of this doha is “Even if the whole earth is transformed into paper with all the big trees made into pens and if the entire water in the seven oceans are transformed into writing ink, even then the glories of the Guru cannot be written. So much is the greatness of the Guru.” Guru means a teacher, master, mentor etc. -

Mentors – Katha

Mentors – Katha about our work act now 300m storyshop .ST0{DISPLAY:NONE;} .ST1{DISPLAY:INLINE;} KATHA UTSAV MENTORS ARUNIMA MAZUMDAR, WRITER & JOURNALIST Arunima works with Roli Books, one of the foremost Indian publishing houses of India. She has worked as a journalist in the past and ABOUTcontinues to US write on arts, culturePROGRAMMES and travel for various publicationsQUICKLINKS such as The Hindu Business Line, Scroll, Femina, and Mumbai Mirror. Books are her best friend and she has keen interest in travel literature, written especially by Who we are 300M Donate Indian authors. Katha Books Katha Lab School Donate Books Storystop ILR Communities Volunteer ANKIT CHADHA – WRITER & STORYTELLER KATHA, A3, Sarvodaya Katha in the News ILR Government Schools Who we are Enclave, Sri AurobindoAnkit ChadhaWhat’s isour a writer-storytellerType whoKatha brings Utsav together performance, literatureWork With and Us history. He specializes in Dastangoi – the Marg, New Delhi - 110017art of Urdu storytelling, and has written, translated, compiled and performed stories under the direction of Mahmood Padho Pyar Se Contact Us Farooqui. His first book for children, the national award-winning My Gandhi Story was published by Tulika in 2013. © Copyright 2017. All Rights Reserved ARVIND GAUR Arvind Gaur, Indian director, is known for his work in innovative, socially and politically relevant theatre.Gaur’s plays are contemporary and thought-provoking, connecting intimate personal spheres of existence to larger social political issues. His work deals with Internet censorship, communalism, caste issues, feudalism, domestic violence, crimes of state, politics of power, violence, injustice, social discrimination, marginalization, and racism. Arvind is the leader of Asmita, Delhi‘s “most prolific theatre group”, and is an actor trainer, social activist, street theatre worker and story teller. -

EWS 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri

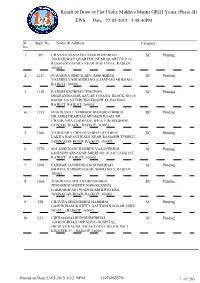

Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri GRIH Yojna (Phase-II) EWS Date : 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category No. 1 99 CHAVDA SANJAYKUMAR PITHABHAI SC Pending 560 RAILWAY QUARTER, NEAR QUARTER P 14, RUKHADIYAPARA NEAR MAFATIYA, RAJKOT, 360002 2 1117 PURABIYA SIMPALBEN ASHOKBHAI SC Pending VALMIKI VADI SHERI NO 4, JAMNAGAR ROAD, , RAJKOT, 360001 3 1119 RAJESH NAJIBHAI CHAUHAN SC Pending DHARAMNAGAR AAVAS YOJANA, BLOCK NO 10 ROOM 286 SATERLING HOSPITAL PACHAD, RAJKOT, RAJKOT, 360001 4 1155 MAKWANA LAXMIBEN BHAGIRATHBHAI SC Pending DR AMBEDKARNAGAR MAIN ROAD, NR CHAMUNDA GARRAGE, B\H S T WORKSHOP, GONDAL ROAD, , RAJKOT, 360001 5 1160 VADODARA CHHAGANBHAI JIVABHAI SC Pending LAKHA BAPANI WADI, NEAR RAMAPIR TEMPLE, JAMNAGAR ROAD, RAJKOT, 360002 6 1279 SOLANKI KANCHANBEN VASANTBHAI SC Pending KHOADIYARNAGAR SHERI NO 18 AJI VASAHAT, RAJKOT, , RAJKOT, 360003 7 1309 PARMAR JAGDISHBHAI SOMABHAI SC Pending BH RTO, NARSHINAGAR, SHERI NO 5, RAJKOT, 360001 8 1364 MAKWANA MILAN BHANUBHAI SC Pending JUMABHAI MISTRY NAMAKANMA, LAKHABAPANI WADI SLAM KWATERS, JAMNAGAR ROAD, RAJKOT, 360001 9 528 CHAVDA SHAMJIBHAI HAJIBHAI SC Pending GADHIGRAM SOCIETY GAUTAM NAGAAR SARY NO 02, , , RAJKOT, 360001 10 531 CHUDASMA DILIP BHIMJIBHAI SC Pending 150 RINGROAD OPP SLING HOSPITAL, DHARAMNAGAR AWAS YOJNA BLOCK NO 1 KWATER-17, , RAJKOT, 360001 Printed on Date 22-05-2015 6:12:19PM 139769655791 1 of 203 Result of Draw of Flat Under Mukhya Mantri GRIH Yojna (Phase-II) EWS Date : 22-05-2015 5:48:40PM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category No. 11 532 -

Kabir: Towards a Culture of Religious Pluralism

198 Dr.ISSN Dharam 0972-1169 Singh Oct., 2003–Jan. 2003, Vol. 3/II-III KABIR: TOWARDS A CULTURE OF RELIGIOUS PLURALISM Dr. Dharam Singh Though globalization of religion and pluralistic culture are more recent terms, the human desire for an inter-faith culture of co- existence and the phenomenon of inter-faith encounters and dialogues are not entirely new. In the medieval Indian scenario we come across many such encounters taking place between holy men of different and sometimes mutually opposite religious traditions. Man being a social creature by nature cannot remain aloof from or indifferent to what others around him believe in, think and do. In fact, to bring about mutual understanding among people of diverse faiths, it becomes necessary that we learn to develop appreciation and sympathy for the faith of the others. The medieval Indian socio-religious scene was dominated by Hinduism and Islam. Hinduism has been one of the oldest religions of Indian origin and its adherents in India then, as even today, constituted the largest majority. On the other hand, Islam being of Semitic origin was alien to India until the first half of the 7th century when the “first contacts between India and the Muslim world were established in the South because of the age- old trade between Arabia and India.”1 However, soon these traders tuned invaders when Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni led a long chain of invasions on India and molestation of Indian populace. To begin with, they came as invaders, plundered the country-side and went back, but soon they settled as rulers. -

Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition

All glory to Śrī Guru and Śrī Gaurāṅga Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh All glory to Śrī Guru and Śrī Gaurāṅga Kīrtan Guide Pocket Edition Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh ©&'() Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math All rights reserved by The Current President-Acharya of Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math Published by Sri Chaitanya Saraswat Math Kolerganj, Nabadwip, Nadia Pin *+()'&, W.B., India Compiled by Sripad Bhakti Kamal Tyagi Maharaj Senior Editor Sripad Mahananda Das Bhakti Ranjan Editor Sri Vishakha Devi Dasi Brahmacharini Proofreading by Sriman Sudarshan Das Adhikari Sriman Krishna Prema Das Adhikari Sri Asha Purna Devi Dasi Cover by Sri Mahamantra Das Printed by CDC Printers +, Radhanath Chowdury Road Kolkata-*'' '(, First printing: +,''' copies Contents Jay Dhvani . , Ārati . Parikramā . &/ Vandanā . ). Morning . +, Evening . ,+ Vaiṣṇava . ,. Nitāi . 2, Gaurāṅga . *& Kṛṣṇa . .* Prayers . (', Advice . ((/ Śrī Śrī Prabhupāda-padma Stavakaḥ . ()& Śrī Śrī Prema-dhāma-deva Stotram . ()2 Holy Days . (+/ Style . (2* Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh . (*. Index . (*/ Dedication This abridged, pocket size edition of Śrī Chaitanya Sāraswat Maṭh’s Kīrtan Guide was offered to the lotus hands of Śrīla Bhakti Nirmal Āchārya Mahārāj on the Adhivās of the Śrī Nabadwīp Dhām Parikramā Festival, && March &'(). , Jay Dhvani Jay Saparikar Śrī Śrī Guru Gaurāṅga Gāndharvā Govindasundar Jīu kī jay! $%&"'( Jay Om Viṣṇupād Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakāchārya-varya Aṣṭottara-śata-śrī Śrīmad Bhakti Nirmal Āchārya Mahārāj !"# kī jay! Jay Om Viṣṇupād Paramahaṁsa -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 9, Issue 12 December, 2015

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 9, Issue 12 December, 2015 HARI OM In Month of November, many activities were performed in temple and many devotees attended various programs. Sri Balaji Guru Vandana was celebrated grandly with 108 kalasha Ganapathi abhishekam, 108 kalasha Balaji abhishekam, Mahalakshmi abhishekam and Sathya Narayana Pooja. On Friday 20th November, 108 kalasha sthapana (presenting to God) for Balaji abhishekam was done. Families sat individually and invoked almighty lord doing sankalpa (resolution) and performed Ganapthi, Navagraha Poojas and Mahalakshmi abhishekam. Pitathipathi Sri Narayananada Swamiji initiated and led all the devotees in reciting mantras. Later, everyone was enchanted with the Mahalakshi abhishekam. Vittal Nithyananda Swami spoke about the meaning of Guru (Teacher). He talked about how the temple has grown today since the 2006 Charasthapatha of Balaji into a spacious place where devotees can come to feel one with God anytime and also how the Balaji Guru Vandana has become such a grand event every year. He Sri Balaji Guru Vandana, Swamiji talked of how Swamiji had a vision of Lord Balaji and how that vision has Praying to lord Sri Satyanarayana for devotes turned into a reality by which devotees are all able to come here to see and and world peace. pray to all the gods and goddesses. By performing Guru Vandana, devotees can feel closer to God and through performing the poojas, all their doshas (problems) are removed. Later, Mahaprasadam sponsored by Peacock sreyo hi jnanam abhyasaj jnanad dhyanam visisyate | Cupertino (Sri Ram Gopal) was served to everyone. dhyanat karma-phala-tyagas tyagac chantir anantaram || On Saturday 21st November, 108 kalasha abhisheka was performed to invoke Lord Balaji and Swamiji performed this abhisheka with help from other priest’s and devotees. -

Govt Revives Hubballi-Ankola Rail Project, Greens See Red Over Loss of 1,500 Acres of Forest

DELHCI i ty 3B3an°gCalore EMngulmishbai | DEeplahpier |HGydadegraebtsaNdow Kolkata Chennai AgartalaClaiAmg ryaourA 1j mpoerint AmSaIGraNva ItNi CITY NEWS / CITY NEWS / BANGALORE NEWS / CIVIC ISSUES / GOVT REVIVES HUBBALLI-ANKOLA RAIL PROJECT, GREENS SEE RED OVER LOSS OF 1,500 ACRES OF FOREST TOP SEARCHES: Bellandur lake Bangalore metro Bangalore weather Floods in Bangalore Bangalore rains Govt revives Hubballi-Ankola rail project, greens see red over loss of 1,500 acres of forest Rohith BR | TNN | Sep 7, 2018, 07:46 IST BENGALURU: Even as experts raise concerns over deforestation in the Western Ghats, the Karnataka government has revived the controversial Hubballi-Ankola railway line project, for which close to 1,500 acres of forest with 2lakh trees have to be cleared. (Picture used for representational purpose) Though the State Wildlife Board has rejected the proposal for the line that passes through Karwar, Yellapur and Dharwad forest divisions, the government has now appealed to the National Board for Wildlife (NBW), which will hear the matter shortly. Environmentalists have also approached NBW, pointing out that a major part of the line alignment passes through Uttara Kannada district, which has the highest forest cover in the state. “The area through which the proposed railway alignment passes is one of the habitats for species like tiger, great Indian hornbill, king cobra and Asiatic elephant. The Biodiversity Impact Assessment Report stated that the project will have negative impacts like changes in land cover, loss of trees and habitat of wild animals, risks due to landslides, mudslides, smuggling of timber and forest goods, contamGinoavt iroenvi voefs land and water Heatvce, ”a ns acidre Gofiridhar KulkarnFi,i rast wcrimldinliaf le c aascetivist. -

Journalism Is the Craft of Conveying News, Descriptive Material and Comment Via a Widening Spectrum of Media

Journalism is the craft of conveying news, descriptive material and comment via a widening spectrum of media. These include newspapers, magazines, radio and television, the internet and even, more recently, the cellphone. Journalists—be they writers, editors or photographers; broadcast presenters or producers—serve as the chief purveyors of information and opinion in contemporary mass society According to BBC journalist, Andrew Marr, "News is what the consensus of journalists determines it to be." From informal beginnings in the Europe of the 18th century, stimulated by the arrival of mechanized printing—in due course by mass production and in the 20th century by electronic communications technology— today's engines of journalistic enterprise include large corporations with global reach. The formal status of journalism has varied historically and, still varies vastly, from country to country. The modern state and hierarchical power structures in general have tended to see the unrestricted flow of information as a potential threat, and inimical to their own proper function. Hitler described the Press as a "machine for mass instruction," ideally, a "kind of school for adults." Journalism at its most vigorous, by contrast, tends to be propelled by the implications at least of the attitude epitomized by the Australian journalist John Pilger: "Secretive power loathes journalists who do their job, who push back screens, peer behind façades, lift rocks. Opprobrium from on high is their badge of honour." New journalism New Journalism was the name given to a style of 1960s and 1970s news writing and journalism which used literary techniques deemed unconventional at the time. The term was codified with its current meaning by Tom Wolfe in a 1973 collection of journalism articles. -

Arts a LIVING TEMPLE - (PHAD PAINTING in RAJASTHAN)

[Mahawar *, Vol.6 (Iss.3): March, 2018] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- c2394-3629(P) (Received: Feb 01, 2018 - Accepted: Mar 22, 2018) DOI: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v6.i3.2018.1521 Arts A LIVING TEMPLE - (PHAD PAINTING IN RAJASTHAN) Dr. Krishna Mahawar *1 *1 Assistance Professor (Painting), Rajasthan University, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Abstract I consider Phad Painting as a valuable pilgrimage of Rajasthan. Phad painting (Mewar Style of painting) or Phad is a stye religious scroll painting and folk painting, practiced in Rajasthan state of India. This is a unique scroll making folk art; this style of painting is traditionally done on a long piece of cloth or canvas, known as phad. It is synonymous with the Bhopa community of the state. These are beautiful specimen of the Rajasthani cloth paintings. The narratives of the folk deities of Rajasthan, mostly of Pabuji and Devnarayan- who are worshipped as the incarnation of lord Vishnu & Laxman. Each hero-god has a different performer-priest or Bhopa. The repertoire of the bhopas consists of epics of some of the popular local hero-gods such as Pabuji, Devji, Tejaji, Gogaji, Ramdevji.The Phad also depict the lives of Ramdev Ji, Rama, Krishna, Budhha & Mahaveera. The iconography of these forms has evolved in a distinctive way. Shahpura in Bhilwara district of Rajasthan are widely known as the traditional artists of this folk art-form for the last two centuries. Presently, Shree Lal Joshi, Nand Kishor Joshi, Prakash Joshi and Shanti Lal Joshi are the most noted artists of the phad painting, who are known for their innovations and creativity. -

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

Falun Gong in the United States: an Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-18-2003 Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Porter, Noah, "Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study" (2003). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALUN GONG IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY by NOAH PORTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: S. Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Michael Angrosino, Ph.D. Kevin Yelvington, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 18, 2003 Keywords: falungong, human rights, media, religion, China © Copyright 2003, Noah Porter TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................... -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ