The Responsive Eye by William C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

T Want There to Be Anything Mysterious About the Way That I Work,' She Says

NG BR text pp1-78 270x230mm v8_AJ / text / pp1-64 / 5 21/10/2010 16:23 Page 14 NG BR text pp1-78 270x230mm v8_AJ / text / pp1-64 / 5 21/10/2010 16:23 Page 15 Fig. 7 Bridget Riley Red with Red 1, 2007 Oil on linen, 177.5 ¥ 255 cm Private collection Fig. 8 Raphael (1483–1520) Saint Catherine of Alexandria, about 1507 (detail) Oil on poplar, 72.2 ¥ 55.7 cm The National Gallery, London (ng 168) and she is happy for them to be seen. ‘I don’t want there to be anything mysterious about the way that I work,’ she says. ‘I mean there is doubt and uncertainty, and the very act of enquiry means that things go wrong and have to be changed and revised. But to me this is part of the pleasure of working.’4 These are just three of the many surviving studies that Seurat used to gather the visual information with which he built his final composition. One study selected by Riley, A River Bank (The Seine at Asnières), about 1883 (plate 20), establishes the location, where he pins down the diagonal division between water and river bank. Seurat makes special use of the striped tidal-measuring post, which helps to carefully balance the compositional components of horizontal, diagonal and vertical. In Study for ‘Bathers at Asnières’, 1883–4 (plate 19), he makes notations of some of the figures that will eventually relate to this location. Lastly, in The Rainbow: Study for ‘Bathers at Asnières’, 1883 (plate 21), he begins to integrate the figures into the space. -

Bridget Riley's Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Artsy Cohen, Alina: Bridget Riley‘s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On November 2019 Bridget Riley’s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On Alina Cohen Nov 1, 2019 11:47am Bridget Riley, 1963. Photo by Ida Kar. © National Portrait Gallery, Bridget Riley Blue Dominance, 1977 London. ARCHEUS/POST- MODERN British artist Bridget Riley, who is known for bold, blocky, and striped canvases of brilliant hues and contrasts, got her Drst taste of international celebrity back in 1965. Curator William Seitz included two of her paintings, Current (1964) and Hesitate (1964), in his groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, titled “The Responsive Eye.” The eye-popping black-and-white squiggles of Riley’s Current adorned the catalogue cover, asserting Riley’s prominent position within the show. The exhibition situated her among an impressive roster of global artists whose artwork reconsidered ideas about perception. The group included American painters ranging from Morris Louis to Agnes Martin, along with Brazilian artist Almir da Silva Mavignier and a Spanish collective called Equipo 57. Along with Mavignier, Riley was considered part of a new wave of “Op artists” who exploited visual principles to make work that seemed to vibrate with new energy. Josef Albers, Salvador Dalí, and the museum-going public all swooned at Riley’s work. maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London While Op art has gone in and out of style, Riley herself is still working and is beloved on both sides of the pond. London’s Hayward Gallery is displaying a major Riley retrospective through January 26th, celebrating over six decades of the artist’s bold geometric abstratractions. -

The Late Richard Anuszkiewicz's Work Is a Rigorous Yet Joyous Exploration

THE MIND’S EYE EYE S ’ MIND THE The late Richard Anuszkiewicz’s work is a rigorous yet The term “Op Art” was invented by a critic, not an artist, the way color affects the human eye, mind, and spirit. joyous exploration of the realm of pure color and form. and the movement to which it was applied—if movement it Anuszkiewicz’s paintings and prints are instantly recognizable was—came and went within a span of about five years in the for their bold contrasts between complementary colors, their geo- By John Dorfman mid- to late 1960s. But the work of Richard Anuszkiewicz, who metrically rigorous organization, and their intricate use of fine was hailed as one of Op’s two greatest practitioners, lives on, a lines. To 21st-century eyes, they look as if they could have been This page: Richard Anuszkiewicz, Dynamic Blue Eclipse, acrylic on wood panel, 18 x 18 in. Opposite: Soft Orange, 1972, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in. COURTESY OF THE OF ESTATE RICHARD ANUSZKIEWICZ © 2021 THE OF ESTATE RICHARD ANUSZKIEWICZ.RIGHTS SOCIETY, ALL NEW RIGHTS YORK, RESERVED. NY AT ARSNY.COM; GIFT LICENSED OF THE MINT BY ARTISTS MUSEUM AUXILIARY. 1974.12.© 2021 THE COURTESY OF ESTATE RICHARD THE ANUSZKIEWICZ. MINT MUSEUM OF ART, CHARLOTTE, ALL RIGHTS NC RESERVED. LICENSED BY ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY, NEW YORK, NY AT ARSNY.COM unique contribution to abstract art and to our understanding of made with computer software, but in fact they are hand-made, 62 ART&ANTIQUES FEBRUARY 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 ART&ANTIQUES 63 THE MIND S EYE EYE S MIND THE HOOD MUSEUM OF ART, DARTMOUTH: GIFT OF THE ARTIST © 2021 THE OF ESTATE RICHARD ANUSZKIEWICZ. -

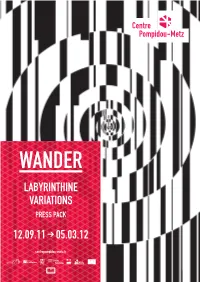

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Seduced Copies of Measured Drawings Written

m Mo. DC-671 .-£• lshlH^d)lj 1 •——h,— • ULU-S-S( f^nO District of Columbia arj^j r£Ti .T5- SEDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Building Survey National Park Service Department of the Interior" Washington, D.C 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DUMBARTON OAKS PARK HABS No. DC-571 Location: 32nd and R Sts., NW, Washington, District of Columbia. The estate is on the high ridge that forms the northern edge of Georgetown. Dumbarton Oaks Park, which was separated from the formal gardens when it was given to the National Park Service, consists of 27.04 acres designed as the "naturalistic" component of a total composition which included the mansion and the formal gardens. The park is located north of and below the mansion and the terraced formal gardens and focuses on a stream valley sometimes called "The Branch" (i.e., of Rock Creek) nearly 100' below the mansion. North of the stream the park rises again in a northerly and westerly direction toward the U.S. Naval Observatory. The primary access to the park is from R Street between the Dumbarton Oaks estate and Montrose Park along a small lane presently called Lovers' Lane. Present Owner; Dumbarton Oaks Park is a Federal park, owned and maintained by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. Dates of Construction: Dumbarton Oaks estate was acquired by Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss in 1920. At their request, Beatrix Jones Farrand, a well- known American landscape architect, agreed to undertake the design and oversee the maintenance of the grounds. -

52 Brook's Mews. Mayfair, W1K 4ED T: 02074953101 E: [email protected]

Press Release Not So Original: Carlos Cruz-Diez, León Ferrari, Terry Frost, Cipriano Martinez, Bridget Riley, Jesus Soto and Emilia Sunyer 8th November – 25th January 2014 This November Maddox Arts will be staging ‘Not So Original’ an exhibition that delves into the symbiotic relationship between the print and the original. Though printmaking is often assumed to be an afterthought in an artist’s practice ‘Not So Original’ demonstrates the variety of roles it may play, spurring the artist’s imagination and engaging in a dialogue with their primary practices. Taking Walter Benjamin’s seminal ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ as it's starting point, ‘Not So Original’ features the work of five, celebrated 20th century printmakers: Bridget Riley, Carlos Cruz-Diaz, Leon Ferrari, Terry Frost and Jesus Soto, alongside the emerging talents of Cipriano Martinez and Emilia Sunyer. From the Middle Ages to the advent of the digital era, technology has allowed artists to disseminate their images in the form of reproductions to a wider audience than a single canvas would ever be able to reach. In facing the prospect of engaging a wider audience artists are often compelled to formalize their style so that a singular print may surmise an artist’s catalogue. Likewise such technologies have enabled art lovers to acquire a ‘piece’ of an original via a process in which the artist may have had no hand. The rise of e-editions and 3D printing ask further questions as to how we distinguish the original from the reproduction, when an infinite number of copies can be instantly and flawlessly reproduced indefinitely. -

Minerva Auctions

MINERVA AUCTIONS ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 MINERVA AUCTIONS Palazzo Odescalchi Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 - 00187 Roma Tel: +39 06 679 1107 - Fax: +39 06 699 23 077 [email protected] www.minervaauctions.com FOLLOW US ON: Facebook Twitter Instagram LIBRI, AUTOGRAFI E STAMPE GIOIELLI, OROLOGI E ARGENTI Fabio Massimo Bertolo Andrea de Miglio Auction Manager & Capo Reparto Capo Reparto Silvia Ferrini Beatrice Pagani, Claudia Pozzati Office Manager & Esperto Amministratori DIPINTI E DISEGNI ANTICHI FOTOGRAFIA Valentina Ciancio Marica Rossetti Capo Reparto Specialist Adele Coggiola Junior Specialist & Amministratore Public Relations Muriel Marinuzzi Ronconi Amministrazione Viola Marzoli ARTE DEL XIX SECOLO Magazzino e spedizioni Claudio Vennarini Luca Santori Capo Reparto ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA Georgia Bava Capo Reparto Photo Stefano Compagnucci Silvia Possanza Layout Giovanni Morelli Amministratore Print CTS Grafica srl MINERVA AUCTIONS ROMA 111 ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 ROMA, PALAZZO ODESCALCHI Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 PRIMA TORNATA - ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) SECONDA TORNATA - ORE 16 (LOTTI 170 - 349) ESPERTO / SPECIALIST Georgia Bava [email protected] REPARTO / DEPARTMENT Silvia Possanza [email protected] Per partecipare a questa asta online: www.liveauctioneers.com www.invaluable.com ESPOSIZIONE / VIEWING ROMA Da venerdì 24 a lunedì 27 aprile, ore 10.00 - 18.00 PREVIEW Per visionare i nostri cataloghi visitate il sito: ROMA www.minervaauctions.com Giovedì 23 aprile, ore 18.00 PRIMA TORNATA ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) Lotto 1 α 1 Jannis Kounellis (Pireo 1936) ROSA cartoncino sagomato e carta Japon nacrè, es.1/12, cm 76,5 x 57 Firma a matita in basso a sinistra Una piega al margine inferiore e tracce di umidità ai margini ed al verso. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 the Continent That the EU Does Not Know

Art in Europe 1945 Art in — 1968 The Continent EU Does that the Not Know 1968 The The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 Supplement to the exhibition catalogue Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Phase 1: Phase 2: Phase 3: Trauma and Remembrance Abstraction The Crisis of Easel Painting Trauma and Remembrance Art Informel and Tachism – Material Painting – 33 Gestures of Abstraction The Painting as an Object 43 49 The Cold War 39 Arte Povera as an Artistic Guerilla Tactic 53 Phase 6: Phase 7: Phase 8: New Visions and Tendencies New Forms of Interactivity Action Art Kinetic, Optical, and Light Art – The Audience as Performer The Artist as Performer The Reality of Movement, 101 105 the Viewer, and Light 73 New Visions 81 Neo-Constructivism 85 New Tendencies 89 Cybernetics and Computer Art – From Design to Programming 94 Visionary Architecture 97 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Introduction Praga Magica PETER WEIBEL MICHAEL BIELICKY 5 29 Phase 4: Phase 5: The Destruction of the From Representation Means of Representation to Reality The Destruction of the Means Nouveau Réalisme – of Representation A Dialog with the Real Things 57 61 Pop Art in the East and West 68 Phase 9: Phase 10: Conceptual Art Media Art The Concept of Image as From Space-based Concept Script to Time-based Imagery 115 121 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know ZKM_Atria 1+2 October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017 4 At the initiative of the State Museum Exhibition Introduction Center ROSIZO and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, the institutions of the Center for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR), the Pushkin Museum, and ROSIZIO planned and organized the major exhibition Art in Europe 1945–1968 in collaboration with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. -

Rome – Milan: Space and Colour, Rhythm and Matter 1 October

Press Release Rome – Milan: Space and Colour, Rhythm and Matter 1 October – 28 November 2020 Private View: 1 October 2020, 12-8pm by appointment Mazzoleni is delighted to announce the launch of the new exhibition season in its London gallery on 1 October 2020, with the group show Rome – Milan: Space and Colour, Rhythm and Matter. The show brings together a number of the leading figures of the Italian art scene that were operating in these two major Italian cities with works realised mainly between the 1950s and 1960s. Acclaimed for their artistic revolutions, pioneers Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) and Alberto Burri (1915-1995) were the points of departure and reference for the experimentation later conducted by the artists born in the 1930s such as Agostino Bonalumi (1935-2013), Enrico Castellani (1930-2017), Dadamaino (1930-2004), Jannis Kounellis (1936-2017), Piero Manzoni (1933-1963) and Mario Schifano (1934-1998). They were to explore new and further strands of research as their artistic careers evolved. Fontana’s innovative reflections on space and Burri’s in-depth experimentation with materials were to be the driving forces behind the development of new artistic idioms. In parallel, predominantly through painting, Giulio Turcato (1912-1995), Piero Dorazio (1927-2005) and Carla Accardi (1924 -2014) (already members of the group Forma 1) combined a skilled use of shapes and colours with new “painterly” materials such as, foam rubber, enamels and casein. Meanwhile Giuseppe Capogrossi (1900-1972), the founder with Burri of the Origine group, developed a personal sign alphabet. In sculpture, from his debut alongside Lucio Fontana, Fausto Melotti (1901-1986) developed a lyrical and poetic dimension that led him to a truly unique artistic path of the Italian art scene. -

Gego Solo Exhibition

GEGO SOLO EXHIBITION 2020 Gego, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico 2019 Gego, Museo de Arte de São Paulo, São Paul, Brazil 2017 Between the lines. Gego as a printmaker, Amon Carter Museum,Texas, United States Gego. A fascination for line, Kunstmuseum Sttutgart, Sttutgart, Germany Gego en 1969 with “Reticulárea” in Caracas, Venezuela Hamburg, Germany, 1912 - Caracas, Venezuela, 1994 Gego: La poetique de la Ligne, Colección 2014 Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt) studied architecture and Mercantil, La Maison de la Amerique Latine, engineering at the Stuttgart Technical School Paris, France (Germany), where she was tutored by architect Paul Bonatz, following the models of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism. In 1939, due to persecution Gego: Line as Object, Kunstmuseum from the Nazi regime, she migrated to Venezuela, Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany making Caracas her home. Once there, Gego dedicated to design, particularly of Gego: Line as Object, Henry Moore furniture, and the development of architectural Institute, Leeds, England projects. Additionally, she began a long teaching career that would lead her to be one of the founders and subsequent professors of the Institute of Design 2013 Gego: El trazo transparente, Museo de la from the Neumann Foundation (Caracas) in 1964. It was during the 1950s that she deepened her artistic Estampa y el Diseño Carlos CruzDiez, practice, which was at first of a figurative, expressionist Caracas, Venezuela type, and then, already in dialogue with kinetic artists like Alejandro Otero and Jesús Soto, of a sculptural type, grounded upon spectator participation, action, Gego: Tejeduras, Bichitos y Libros, Periférico and movement as key principles of production. de Caracas / Arte Contemporáneo/Centro de Arte Los Galpones, Caracas, Venezuela Her work is characterized by the experimentation with lines upon space, conceived as the most elemental unit of drawing, as well as for the innovative use of the Gego: Line as Object, Hamburger Kunsthalle, reticule, a form intimately related to abstraction in Hamburg, Germany modern art.