Modern Abstraction in Latin America Cecilia Fajardo-Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark's Therapeutic

Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Eleanor R. Harper June 2010 © 2010 Eleanor R. Harper. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice by ELEANOR R. HARPER has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jaleh Mansoor Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT HARPER, ELEANOR R., M.A., June 2010, Art History Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice (125 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jaleh Mansoor This thesis examines the oeuvre of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920-1988) with respect to her progressive interest in and inclusion of the viewing subject within the work of art. Responding to the legacy of Portuguese occupation in her home of Brazil, Clark sought out an art that embraced the viewing subject and contributed to their sense of subjectivity. Challenging traditional models of perception, participation, and objecthood, Clark created objects that exceeded the bounds of the autonomous transcendental picture plane. By fracturing the surfaces of her paintings, creating objects that possess an interior and exterior, and by requiring her participants to physically manipulate her work, Clark demonstrated an alternative model of the art object and experience. These experiments took her into the realm of therapy under the influence of psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s work. -

Sicardi Gallery 1506 W Alabama St H Ouston, TX 77006 Tel. 713 529

Sicardi Gallery Magdalena Fernández Flexible Structures , 2017. 2i000.017 Iron spheres with black elastic cord, variable dimensions variable with black elastic cord, spheres Iron Molick © Peter 1506 W Alabama St Houston, TX 77006 Tel. 713 529 1313 sicardigallery.com A white line traverses the dark wall in Magdalena ple networks and transnational interconnections. January 12 to Fernández’s video 10dm004. Ambiguous as to Moreover, modernization, the third term in the whether it is a connection between two points, a triad—modernity-modernism-modernization— March 11, 2017 slice cutting two spaces, or the trace of a vibra- assumes a universal model of development also tion, the line gently undulates from right to left, established by the West that divides the globe occasionally resting flat during a fifteen minute into developed and underdeveloped nations.4 loop. The 2004 video was created through the Houston and Caracas’s shared growth as a result simplest of means by reflecting light on a pool of international markets contradicts this world- of water then recording agitations on the sur- view and insists on a more complex account than face.1 What at first appears as a beautiful formal a strict center-periphery connection. exercise thus implies a connective metaphor for water, one that is particularly appropriate for Fernández’s videos, drawings, and sculptures Fernández’s debut solo exhibition in Houston. point toward a nimble version of modernism, and by implication modernity and modernization. Al- The Texas metropolis lies across the sea from the luding to the strict geometries of mid-century artist’s home in Caracas, and the two cities are artists such as Piet Mondrian and Sol LeWitt as united not only by an expanse of water but also well as Gego and Carlos Cruz-Diez, she opens their shared history of modernization as a result their fixed forms to movement, chance, and inter- of the extraction and processing of fossil fuels. -

©2010, Hilton Andrade De Mello Todos Os Direitos Reservados

©2010, Hilton Andrade de Mello Todos os direitos reservados Ao Leonardo, Rafael, Ana Clara e Dominique, cuja alegria e criatividade me inspiraram na realização da presente obra. E à memória da Paula, o espírito iluminado e extraordinário que abriu e alegrou os nossos caminhos. HAM (Hamello) Não deixem ninguém sem conhecimento de geometria cruzar a minha porta Em 387 a.C. Platão fundou a sua academia de filosofia em Atenas, que funcionou até o ano 529 d.C., quando foi fechada pelo Imperador Justiniano. Os dizeres acima estavam na entrada da Academia. iv Sumário Agradecimentos vii Sobre o autor viii Introdução ix Capítulo: 1 Abstração e Geometria 1 2 As formas geométricas planas 10 2.1 Euclides de Alexandria 11 2.2 O Método axiomático de Aristóteles 11 2.3 Conceitos primitivos da Geometria Euclidiana 12 2.4 Polígonos 14 2.4.1 Definição 14 2.4.2 Tipos de polígonos 15 2.4.3 Nomes dos polígonos 17 2.4.4 Triângulos 17 2.4.5 Quadriláteros 18 2.4.5.1 Paralelogramos 18 2.4.5.2 Trapézios 21 2.5 Circunferência e círculo 21 2.6 Polígono inscrito e circunscrito 22 2.7 Estrelas 23 2.8 Rosáceas 26 2.9 Espirais 29 2.9.1 Espiral de Arquimedes 29 2.9.2 Espiral de Bernoulli 30 2.9.2 As espirais na nossa vida 30 3 Poliedros 33 3.1 Introdução 34 3.2 Poliedros convexos e côncavos 35 3.3 Famílias interessantes de poliedros 35 3.3.1 Os Sólidos Platônicos 35 3.3.2 Os Sólidos Arquimedianos 36 3.3.3 Sólidos estrelados 36 3.4. -

Jcmac.Art W: Jcmac.Art Hours: T-F 10:30AM-5PM S 11AM-4PM

THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Above: Carmelo Arden Quin, Móvil, 1949. 30 x 87 x 95 in. Cover: Alejandro Otero, Coloritmo 75, 1960. 59.06 x 15.75 x 1.94 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection 3 Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection was founded in 2005 out of a passion for art and a commitment to deepen our understanding of the abstract-geometric style as a significant part of Latin America’s cultural legacy. The fascinating revolutionary visual statements put forth by artists like Jesús Soto, Lygia Clark, Joaquín Torres-García and Tomás Maldonado directed our investigations not only into Latin American regions but throughout Europe and the United States as well, enriching our survey by revealing complex interconnections that assert the geometric genre's wide relevance. It is with great pleasure that we present The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection celebrating the recent opening of Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection’s new home among the thriving community of cultural organizations based in Miami. We look forward to bringing about meaningful dialogues and connections by contributing our own survey of the intricate histories of Latin American art. Juan Carlos Maldonado Founding President Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Left: Juan Melé, Invención No.58, 1953. 22.06 x 25.81 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection explores how artists across different geographical and periodical contexts evaluated the nature of art and its place in the world through the pictorial language of geometric abstraction. -

Oral History Interview with Regina Vater, 2004 February 23-25

Oral history interview with Regina Vater, 2004 February 23-25 This interview is part of the series "Recuerdos Orales: Interviews of the Latino Art Community in Texas," supported by Federal funds for Latino programming, administered by the Smithsonian Center for Latino Initiatives. The digital preservation of this interview received Federal support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Regina Vater on February 23 and 25, 2004. The interview took place in Austin, Texas and was conducted by Cary Cordova for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Recuerdos Orales: Interviews of the Latino Art Community in Texas. Regina Vater and Cary Cordova have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview CARY CORDOVA: This is Cary Cordova for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This is an oral history interview of Regina Vater on February 23, 2004, at her home at 4901 Caswell Avenue in Austin, Texas. And this is session one and disc one. And as I mentioned, Regina, I’m just going to ask if you could tell us a little bit about where you were born and where your family is from originally, and when you were born. REGINA VATER: Okay. -

Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy (Exhibition Catalogue)

KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY OCTOBER 3, 2019 - JANUARY 11, 2020 CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. We are grateful to María Inés Sicardi and the Sicardi-Ayers-Bacino Gallery team for their collaboration and assistance in realizing this exhibition. We sincerely thank the lenders who understood our desire to present work of the highest quality, and special thanks to our colleague Debbie Frydman whose suggestion to further explore kineticism resulted in Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy. LE MOUVEMENT - KINETIC ART INTO THE 21ST CENTURY In 1950s France, there was an active interaction and artistic exchange between the country’s capital and South America. Vasarely and many Alexander Calder put it so beautifully when he said: “Just as one composes colors, or forms, of the Grupo Madí artists had an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires in 1957 so one can compose motions.” that was extremely influential upon younger generation avant-garde artists. Many South Americans, such as the triumvirate of Venezuelan Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy is comprised of a selection of works created by South American artists ranging from the 1950s to the present day. In showing contemporary cinetismo–Jesús Rafael Soto, Carlos Cruz-Diez, pieces alongside mid-century modern work, our exhibition provides an account of and Alejandro Otero—settled in Paris, amongst the trajectory of varied techniques, theoretical approaches, and materials that have a number of other artists from Argentina, Brazil, evolved across the legacy of the field of Kinetic Art. Venezuela, and Uruguay, who exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. -

Carmen Herrera 52-54 Bell Street 1 February – 3 March 2012

Carmen Herrera 52-54 Bell Street 1 February – 3 March 2012 Lisson Gallery is pleased to announce an extensive survey show of paintings by Carmen Herrera. Born in Cuba in 1915, Herrera has worked in Havana, Paris and New York. One of her most comprehensive exhibitions to date, this will include historic paintings from the 1940s through to the present day. Recognition came late for Herrera: a story not uncommon among women of her generation. After seven decades of painting, her work was finally revealed to a wider audience through shows in New York and in the UK at IKON Gallery, Birmingham in 2009. Herrera was instantly recognised as a pioneer of Geometric Abstraction and Latin American Modernism. Her compositions are striking in their formal simplicity and heavily influenced by her architectural studies at the University of Havana, Cuba from 1937 to 1938. Combining line, form and space, the geometric division of the canvas with shapes or lines, complemented by blocks of colour, form the structural basis of each work. Herrera’s early works dating from the mid-1940s anticipated the hard-edged Minimalism of the 1960s. Having moved to Paris from New York in 1948, Herrera found her work taking new direction, departing from her Abstract Expressionist approach to establish a more concrete style. Predominately composed of two contrasting colours punctuated with black, as seen in Untitled (1948-1956), Herrera’s intuitive compositions eliminate reference to the external world, employing the simplicity inherent in their geometric arrangements to imbue an acute physicality and structure. They comprise a harmonious balance of non-representational shapes whose reductive forms simultaneously lie adjacent to and on top of one another. -

ALEJANDRO OTERO B. 1921, El Manteco, Venezuela D. 1990

ALEJANDRO OTERO b. 1921, El Manteco, Venezuela d. 1990, Caracas, Venezuela SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2019 Alejandro Otero: Rhythm in Line and Space, Sicardi Ayers Bacino, Houston, TX, USA 2017 Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art, 1954–1969 - Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Spring, CA 2016 Kazuya Sakai - Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City MOLAA at twenty: 1996-2016 - Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), Long Beach, CA 2015 Moderno: Design for Living in Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, 1940–1978 - The Americas Society Art Gallery, New York City, NY 2014 Impulse, Reason, Sense, Conflict. - CIFO - Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, FL 2013 Donald Judd+Alejandro Otero - Galería Cayón, Madrid Obra en Papel - Universidad Metropolitana, Caracas Intersections - MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, CA Mixtape - MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, CA Concrete Inventions. Patricia Phelp de Cisneros Collection - Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. 2012 O Espaço Ressoante Os Coloritmos De Alejandro Otero - Instituto de Arte Contemporânea (IAC), São Paulo, Brazil Constellations: Constructivism, Internationalism, and the Inter-American Avant-Garde - AMA Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC Caribbean: Crossroads Of The World - El Museo del Barrio, the Queens Museum of Art & The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City, NY 2011 Arte latinoamericano 1910 - 2010 - MALBA Colección Costantini - Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires 2007 Abra Solar. Un camino hacia la luz. Centro de Arte La Estancia, Caracas, Venezuela 2006 The Rhythm of Color: Alejandro Otero and Willys de Castro: Two Modern Masters in the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection - Fundación Cisneros. The Aspen Institute, Colorado Exchange of glances: Visions on Latin America. -

Carlos Cruz-Díez

Todos nuestros catálogos de arte All our art catalogues desde/since 1973 Carlos Cruz-Diez Color Happens 2009 El uso de esta base de datos de catálogos de exposiciones de la Fundación Juan March comporta la aceptación de los derechos de los autores de los textos y de los titulares de copyrights. Los usuarios pueden descargar e imprimir gra- tuitamente los textos de los catálogos incluidos en esta base de datos exclusi- vamente para su uso en la investigación académica y la enseñanza y citando su procedencia y a sus autores. Use of the Fundación Juan March database of digitized exhibition catalogues signifies the user’s recognition of the rights of individual authors and/or other copyright holders. Users may download and/or print a free copy of any essay solely for academic research and teaching purposes, accompanied by the proper citation of sources and authors. www.march.es Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ COLOR HAPPENS Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March This catalogue accompanies the exhibition Carlos Cruz-Diez: Pompidou, Paris; Atelier Cruz-Diez, Paris; and MUBAG (Council Color Happens, the first solo exhibition devoted to the work of Alicante), for their generous help in arranging decisive loans. of Cruz-Diez at a Spanish museum or, to be more precise, two We are also grateful to the Atelier Cruz-Diez Documentation museums. Since the 60s, the works of Cruz-Diez have been Service, especially Catherine Seignouret, Connie Gutiérrez featured in major exhibitions dedicated to Kineticism and in Arena, Ana María Durán and Maïwenn Le Bouder, for their important group shows focusing on Latin American art and assistance in managing and gathering documentation and kinetic movements. -

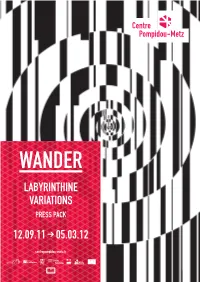

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Carmen Herrera Interviewed by Julia P

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 18, OCTOBER 2020 CARMEN HERRERA INTERVIEWED BY JULIA P. HERZBERG ON DECEMBER 15, 2005, AND JANUARY 10, 2006 Carmen Herrera is a Cuban American painter who lives and works in New York City. In 2017 her work was surveyed in Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight at the Whitney Museum of American Art; the exhibition traveled to the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, and Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, Germany. A selection of recent paintings was shown at New York City’s Lisson Gallery in May 2016. Other solo exhibitions have been at Museum Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany (2010); Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK (2009); and Museo del Barrio, New York City (1998). Her work has also been included in a number of group shows. Julia P. Herzberg is an art historian, independent curator, and writer. As a Fulbright scholar in 2007–11 and 2012–13, she taught at Pontifical Catholic University and Diego Portales University in Santiago, Chile, and curated the exhibition Kaarina Kaikkonen: Two Projects—Traces and Dialogues at the Museum of History and Human Rights and the National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago. Her most recent publications are “Carlos Alfonzo: Transformative Work from Cuba to Miami and the U.S.,” in Carlos Alfonzo: Witnessing Perpetuity (2020) and “A Conversation with María Elena González: A Trajectory of Sound,” in María Elena González: Tree Talk (2019). This interview was conducted as part of the A Ver: Revisioning Art History project. Preferred citation: Carmen Herrera, interview with Julia P. Herzberg, December 15, 2005, and January 6, 2006, New York, New York. -

Carmen Herrera CV

Carmen Herrera Lives and works in New York, NY, USA 1942-43 Arts Students League, New York, USA 1938-39 Architecture, Universidad de La Habana, Havana, Cuba 1933-36 Studied painting and sculpture with Isabel Chappotín Jiménez and María Teresa Gineréde de Villageliú Free study, Lyceum, Havana, Cuba 1929-31 Marymount College, Paris, France 1925-28 Studied drawing and painting with J.F. Edelmann, Havana, Cuba 1915 Born in Havana, Cuba Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 ‘Carmen Herrera in Paris: 1949-1953’, Dickinson Roundell, New York, NY, USA ‘Carmen Herrera: Structuring Surfaces’, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Houston, TX, USA ‘Carmen Herrera: Estructuras Monumentales’, Buffalo Bayou Park, Houston, TX, USA ‘Carmen Herrera: Colour Me In’, The Perimeter, London, UK ‘Carmen Herrera: Painting in Process’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2019 ‘Carmen Herrera: Estructuras Monumentales', Public Art Fund, City Hall Park, New York, NY, USA 2018 ‘Carmen Herrera: Estructuras’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2017 ‘Carmen Herrera’, Lisson Gallery, London, UK ‘Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight’, K20: Kunst Sammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, Westfalen, Germany ‘Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight’, Wexner Center for the Arts, the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA ‘Carmen Herrera: Paintings on Paper’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2016 ‘Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight’, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY, USA ‘Carmen Herrera: Recent Works’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2013 ‘Works on Paper 2010-2012’, Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy 2012 ‘Carmen