T Want There to Be Anything Mysterious About the Way That I Work,' She Says

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridget Riley's Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Artsy Cohen, Alina: Bridget Riley‘s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On November 2019 Bridget Riley’s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On Alina Cohen Nov 1, 2019 11:47am Bridget Riley, 1963. Photo by Ida Kar. © National Portrait Gallery, Bridget Riley Blue Dominance, 1977 London. ARCHEUS/POST- MODERN British artist Bridget Riley, who is known for bold, blocky, and striped canvases of brilliant hues and contrasts, got her Drst taste of international celebrity back in 1965. Curator William Seitz included two of her paintings, Current (1964) and Hesitate (1964), in his groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, titled “The Responsive Eye.” The eye-popping black-and-white squiggles of Riley’s Current adorned the catalogue cover, asserting Riley’s prominent position within the show. The exhibition situated her among an impressive roster of global artists whose artwork reconsidered ideas about perception. The group included American painters ranging from Morris Louis to Agnes Martin, along with Brazilian artist Almir da Silva Mavignier and a Spanish collective called Equipo 57. Along with Mavignier, Riley was considered part of a new wave of “Op artists” who exploited visual principles to make work that seemed to vibrate with new energy. Josef Albers, Salvador Dalí, and the museum-going public all swooned at Riley’s work. maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London While Op art has gone in and out of style, Riley herself is still working and is beloved on both sides of the pond. London’s Hayward Gallery is displaying a major Riley retrospective through January 26th, celebrating over six decades of the artist’s bold geometric abstratractions. -

52 Brook's Mews. Mayfair, W1K 4ED T: 02074953101 E: [email protected]

Press Release Not So Original: Carlos Cruz-Diez, León Ferrari, Terry Frost, Cipriano Martinez, Bridget Riley, Jesus Soto and Emilia Sunyer 8th November – 25th January 2014 This November Maddox Arts will be staging ‘Not So Original’ an exhibition that delves into the symbiotic relationship between the print and the original. Though printmaking is often assumed to be an afterthought in an artist’s practice ‘Not So Original’ demonstrates the variety of roles it may play, spurring the artist’s imagination and engaging in a dialogue with their primary practices. Taking Walter Benjamin’s seminal ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ as it's starting point, ‘Not So Original’ features the work of five, celebrated 20th century printmakers: Bridget Riley, Carlos Cruz-Diaz, Leon Ferrari, Terry Frost and Jesus Soto, alongside the emerging talents of Cipriano Martinez and Emilia Sunyer. From the Middle Ages to the advent of the digital era, technology has allowed artists to disseminate their images in the form of reproductions to a wider audience than a single canvas would ever be able to reach. In facing the prospect of engaging a wider audience artists are often compelled to formalize their style so that a singular print may surmise an artist’s catalogue. Likewise such technologies have enabled art lovers to acquire a ‘piece’ of an original via a process in which the artist may have had no hand. The rise of e-editions and 3D printing ask further questions as to how we distinguish the original from the reproduction, when an infinite number of copies can be instantly and flawlessly reproduced indefinitely. -

Viewership and How These Binaries Function and Appear Within Abstract Painting

Contextualizing Epiphanies and Theories on a Surface of a Painting THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Maija Helena Miettinen-Harris Graduate Program in Art The Ohio State University 2015 Master’s Examination Committee: Laura Lisbon, Advisor George Rush Amanda Gluibizzi Copyright by Maija Helena Miettinen-Harris 2015 Abstract In this thesis I intend to explore the complex, confusing and often paradoxical nature of my painting practice and the way I see it being influenced by historical, socio-political and ideological underpinnings of my reality. During the course of my thesis, I hope to establish a conceptual and contextual basis for my usage of allover pattern-like configurations, rejection of linear perspective, and the manipulation of competing forms and colors in my abstract paintings. I will focus on to the often-elliptical nature of my paintings through variety of ideas and theories and I hope to demonstrate how cultural theory has helped me to contextualize the essential features of my practice. I will first map out the mostly intuitive epiphanies that are rooted in the observations of my reality, which in turn informs the constructions and orientations of my paintings. I will study these in relation to the notions of artist Bridget Riley. I find her writing especially useful in terms of articulating the dichotomy and paradox between active and passive viewership and how these binaries function and appear within abstract painting. I will then examine the circular and expanding theory of liminality by cultural anthropologist Victor Turner, and centers and margins as well as cultural dirt by anthropologist Mary Douglas. -

Bridget Riley Born 1931 in London

This document was updated March 3, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Bridget Riley Born 1931 in London. Live and works in London. EDUCATION 1949-1952 Goldsmiths College, University of London 1952-1956 Royal College of Art, London SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Bridget Riley, Gallery One, London, April–May 1963 Bridget Riley, Gallery One, London, September 9–28 Bridget Riley, University Art Gallery, Nottingham 1965 Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York Bridget Riley, Feigen/Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles 1966 Bridget Riley, Preparatory Drawings and Studies, Robert Fraser Gallery, London, June 8–July 9 Bridget Riley: Drawings, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York 1967 Bridget Riley: Drawings, The Museum of Modern Art (Department of Circulating Exhibitions, USA): Wilmington College, Wilmington, February 12–March 5; and Talladega College, Talladega, March 24–April 16 Bridget Riley, Robert Fraser Gallery, London Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York 1968 Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York British Pavilion (with Phillip King), XXXIV Venice Biennale, 1968; Städtische Kunstgalerie, Bochum, November 23–December 30, 1968; and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 1969 1969 Bridget Riley, Rowan Gallery, London Bridget Riley: Drawings, Bear Lane Gallery, Oxford [itinerary: Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol; Midland Group Gallery, Nottingham] 1970 Bridget Riley: Prints, Kunststudio, Westfalen-Blatt, Bielefeld Bridget Riley: Paintings and Drawings 1951–71, Arts -

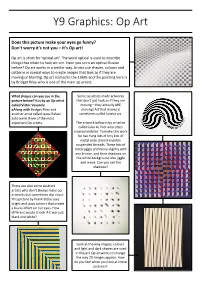

Y9 Graphics: Op Art

Y9 Graphics: Op Art Does this picture make your eyes go funny? Don't worry it's not you – it's Op art! Op art is short for 'optical art'. The word optical is used to describe things that relate to how we see. Have you seen an optical Illusion before? Op art works in a similar way. Artists use shapes, colours and patterns in special ways to create images that look as if they are moving or blurring. Op art started in the 1960s and the painting here is by Bridget Riley who is one of the main op artists. What shapes can you see in the Some op artists made artworks picture below? It is by an Op artist that don't just look as if they are called Victor Vasarely. moving – they actually ARE aAlong with Bridget Riley and moving! Art that moves is another artist called Jesus Rafael sometimes called kinetic art. Soto were three of the most important Op artists. The artwork below is by an artist called Julio Le Parc who often created mobiles. To make this work he has hung lots of tiny bits of metal onto almost invisible suspended threads. These bits of metal jiggle and move slightly with any breeze, and their shadows on the white background also jiggle and move. Can you see the shadows? There are also some abstract artists who don't always make op artworks but sometimes slip into it. This picture by Frank Stella uses bright and jazzy colours that create a buzzy effect on our eyes. -

The Responsive Eye by William C

The responsive eye By William C. Seitz. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in collaboration with the City Art Museum of St. Louis [and others Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1965 Publisher [publisher not identified] Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2914 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art MoMA 757 c.2 r//////////i LIBRARY Museumof ModernArt ARCHIVE wHgeugft. TheResponsive Eye BY WILLIAM C. SEITZ THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CITY ART MUSEUM OF ST. LOUIS, THE CONTEMPORARY ART COUNCIL OF THE SEATTLE ART MUSEUM, THE PASADENA ART MUSEUM AND THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART /4/t z /w^- V TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART David Rockefeller, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, Vice-Chairman;William S. Paley, Vice-Chairman; Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, Vice-Chairman;William A. M. Burden, President; James Thrall Soby, Vice-President;Ralph F. Colin, Vice-President;Gardner Cowles, Vice-President;Wa l ter Bareiss, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., *Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Willard C. Butcher, *Mrs. W. Murray Crane, John de Menil, Rene d'Harnoncourt, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon, Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, *Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Wallace K. Harrison, Mrs. Walter Hochschild, "James W. Husted, Philip Johnson, Mrs. Albert D. Lasker,John L. Loeb, Ranald H. Macdonald, Porter A. McCray, *Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller, Mrs. Charles S. -

The Jeremy Lancaster Collection to Highlight Christie’S Frieze Week

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 29 JULY 2 0 1 9 THE JEREMY LANCASTER COLLECTION TO HIGHLIGHT CHRISTIE’S FRIEZE WEEK DEDICATED EVENING AUCTION ON 1 OCTOBER 2019 Philip Guston, Language I, 1973, estimate: £1,500,000-2,000,000 London – Christie’s Frieze Week programme will be launched with a dedicated auction of the remarkable private collection of Jeremy Lancaster on 1 October 2019. A chorus of vivid colour, radical form and brilliant innovation, the collection showcases some of the greatest achievements in post-war British painting, complemented by a stellar selection of European and American works. Many of the works were acquired through the gallery of Leslie Waddington, and a number have passed through notable collections such as Herbert Read, E. J. Power and Charles Saatchi. Such distinguished provenance is testament not only to a shared championship of the post-war British art scene, but also to the exchange with the European and American avant-gardes in which Waddington and his clients played such a vital role. Several of the works have been on long-term loan to museum collections and Jeremy Lancaster was a trustee at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery of contemporary art and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts. A frequent traveller with a keen appetite for art and knowledge, Jeremy Lancaster was in part influenced by the seminal exhibition ‘A New Spirit in Painting’. Undoubtedly a profound moment in the landscape of contemporary art it was staged by London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1981. The direction of his collecting taste follows a similar dedication to transatlantic discourse in paintings from Frank Auerbach and Howard Hodgkin to Philip Guston, Robert Ryman and Josef Albers. -

Experiencing Landscape Introduction

Teachers’ Resource EXPERIENCING LANDSCAPE INTRODUCTION The Courtauld Gallery’s world-renowned collections The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an extensive include Old Masters, Impressionist and Post- programme of learning activities for young people, Impressionist paintings, an outstanding prints and schools, colleges and teachers. From gallery tours and drawings collection and significant holdings of medieval, workshops to teachers’ events there are many ways for Renaissance and modern arts. The gallery is at the heart schools and students to engage with our collection, of the Courtauld institute of Art, a specialist college exhibitions and the Institute’s expertise. of the University of London and is housed in Somerset House. The Experiencing the Landscape resource is for teachers to learn about the history of Western Our teachers’ resources are based on The Courtauld’s Landscape painting looking at different historical art collection, exhibitions and displays. We are able to and social contexts across time. The resource is use the expertise of our students and scholars in our divided into chapters covering a range of themes. The learning resources to contribute to the understanding, accompanying CD can be used in class or shared with knowledge and enjoyment of art history. The your students and we hope the resource will help bring resources are intended as a way to share research and the subject of Landscape Art, and the artists’ experience understanding about art, architecture and art history. We of landscape, alive for you and your students. The hope that the articles and images will serve as a source resource ends with a glossary of art historical terms to of ideas and inspiration which can enrich lesson content aid your understanding. -

Sotheby's to Offer Art from the British Airways

SOTHEBY’S TO OFFER ART FROM THE BRITISH AIRWAYS COLLECTION Led by Bridget Riley’s Cool Edge Across Auctions in July 2020 LONDON, TUESDAY 14 JULY: Sotheby’s will offer seventeen paintings, prints and works on paper from the British Airways Collection across two auctions in London later this month, including works by some of the very best talent to emerge from Britain in the second half of the last century. The offering will be led by pioneering British female artist, and subject of a recent critically acclaimed retrospective at London’s Hayward Gallery, Bridget Riley. Cool Edge from 1982 (est. £800,000-1.2 million), is one of the finest examples of the artist’s stripe paintings from the 1980s and will be a highlight of Sotheby’s London cross-category Evening Sale, “Rembrandt to Richter”, on July 28th. The painting belongs to the “Egyptian Series” which was celebrated in the artist’s aforementioned Hayward Gallery retrospective exhibition earlier this year. A trip to Egypt in 1979 led to a fascination with the dynamic use of colour in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings, and Cool Edge bears all the hallmark hues of her celebrated ‘Egyptian palette’ - violet, aquamarine, coral and yellow. Many examples reside in the permanent collections of international institutions. Achæan (1981), a work with a remarkably similar colour palette, is a highlight of the Tate Collection, London, and Blue About (1983/2002) is in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Sotheby’s online auction of Modern & Post War British Art (20-30 July) will offer seven further screen prints by Riley from The British Airways Collection, including five works from her Elongated Triangles series of 1971. -

Seriell Formations Introduction Wiehager Engl

Serielle Formationen. 1967/2017 First thematic exhibition on Minimalist trends in Germany at the time Curator 2017: Renate Wiehager. Curators 1967: Paul Maenz and Peter Roehr. Daimler Contemporary Berlin June 3 – November 5, 2017 Opening: June 3, 2017, 11 a.m. – 6 p.m., guided tours all day The exhibition ‘Serielle Formationen’ [ Serial Formations ], jointly curated by Peter Roehr and Paul Maenz for the studio gallery of the University in Frankfurt in 1967, can be seen as the first thematic exhibition on Minimalist trends in Germany. In the context of its exhibition series ‘Minimalism in Germany’, which started in 2005, the Daimler Art Collection is making a first attempt to re-stage the historical presentation. ‘Serielle Formationen’ was an outstanding exhibition that brought together the contemporary trends of the period. In particular, it showed artwork by artists from Germany and elsewhere side by side. A total of 62 artworks by 48 artists were selected because they were pictures and objects with ‘serial order’ as a visual feature—although the concepts behind them were highly diverse and sometimes downright contradictory. The European Zero movement was represented, alongside manifestations of Nouveau Réalisme, Pop and Op Art and American Minimal and Conceptual Art. The exhibition was accompanied by an ambitious catalogue containing six original graphical works and extensive artwork documentation and artist statements. “The ambition of ‘Serielle Formationen’ was to inform and to identify the differences between seemingly similar art phenomena.” (Maenz) The show at Daimler Contemporary Berlin features artworks from the Daimler Art Collection as well as loans from German and International collections. -

Museum Tv - Sotheby’S

Monday, 5 October 2020 Press release MUSEUM TV - SOTHEBY’S WEDNESDAY, 21 OCTOBER 2020 MUSEUM TV TO LIVESTREAM SOTHEBY’S MODERNITÉS-CONTEMPORARY AUCTIONS IN PARIS AND LONDON In a ground-breaking move, on Wednesday, 21 October, Museum TV will Press contact broadcast Sotheby’s auctions of “Modernités” in Paris at 6pm (CEST) and Agence Communic’Art the Contemporary Art Evening sale in London at 8pm (CEST) direct from the Lindsey Williams saleroom. [email protected] Both segments of the auction will be live-streamed, enhanced with dynamic and +33 (0) 7 69 98 73 96 informative on-screen visuals for each of the works offered – an insight into the bidding and buying process on an elevated scale. The two prestigious sales are dedicated to the major artistic periods of the 20th and 21st centuries and will present artworks of the great masters working across Europe and beyond. “MODERNITÉS”, PARIS, 6PM (CEST). Picasso, Soulages, Picabia, Kandinsky... exceptional lots for an extraordinary evening. In Paris, the “Modernités” sale will be taken by Helena Newman, Chairman for Sotheby’s Europe & Worldwide Head of Impressionist and Modern Art. It will offer TELEVISION HISTORY a panorama of artistic creation from 1900 to the Post-war period with works by FOR PARIS Pablo Picasso, Pierre Soulages, Francis Picabia and Wassily Kandinsky and will include a private collection of 25 rarely-seen works, with a total value of more The broadcast will take than 10 million euros / 12 million US Dollars. place live on Museum TV France and Museum Newman will take to the rostrum in the London ‘control centre’ studio, fielding TV International. -

Op Art Spinners

Copyright © 2017 Dick Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com Op Art Spinners Why settle for a manufactured spinner when you can take a one-of-a kind piece of art for a spin? “Fidget spinners” became wildly popular because of their reputation as a concentration aid or a means of releasing stress and anxiety. In the same manner as a stress ball, they give the hands something to keep them busy. Op Art (short for Optical Art) is a movement that rose to popularity in the 1960s as a means of keeping the eyes busy. Optical illusions were not invented by scientists or optometrists but by GRADES 3-12 Note: Instructions artists who understand the workings and materials are based upon a class of the human brain and eyes and size of 24 students. Adjust as needed. how to trick them into believing they see Preparation something they don't actually see. A design that is completely stationery can appear to have movement 1. View mind-boggling examples of Op Art from artists as a result of carefully placed color and pattern. such as Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, Richard Allen and Richard Anuszkiewicz. Art that is designed to incorporate motion is known 2. Use a paper trimmer to cut heavyweight Dura-Lar into as Kinetic Art, and Op Art is considered kinetic even if 5" squares. A 25" x 40" sheet will produce 40 pieces. the motion is only illusionary. You'll need one per student. In this lesson plan, students create their own hand- 3.