An Experimental Investigation of the Movement Known As Op Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

T Want There to Be Anything Mysterious About the Way That I Work,' She Says

NG BR text pp1-78 270x230mm v8_AJ / text / pp1-64 / 5 21/10/2010 16:23 Page 14 NG BR text pp1-78 270x230mm v8_AJ / text / pp1-64 / 5 21/10/2010 16:23 Page 15 Fig. 7 Bridget Riley Red with Red 1, 2007 Oil on linen, 177.5 ¥ 255 cm Private collection Fig. 8 Raphael (1483–1520) Saint Catherine of Alexandria, about 1507 (detail) Oil on poplar, 72.2 ¥ 55.7 cm The National Gallery, London (ng 168) and she is happy for them to be seen. ‘I don’t want there to be anything mysterious about the way that I work,’ she says. ‘I mean there is doubt and uncertainty, and the very act of enquiry means that things go wrong and have to be changed and revised. But to me this is part of the pleasure of working.’4 These are just three of the many surviving studies that Seurat used to gather the visual information with which he built his final composition. One study selected by Riley, A River Bank (The Seine at Asnières), about 1883 (plate 20), establishes the location, where he pins down the diagonal division between water and river bank. Seurat makes special use of the striped tidal-measuring post, which helps to carefully balance the compositional components of horizontal, diagonal and vertical. In Study for ‘Bathers at Asnières’, 1883–4 (plate 19), he makes notations of some of the figures that will eventually relate to this location. Lastly, in The Rainbow: Study for ‘Bathers at Asnières’, 1883 (plate 21), he begins to integrate the figures into the space. -

Bridget Riley's Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Artsy Cohen, Alina: Bridget Riley‘s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On November 2019 Bridget Riley’s Paintings Continue to Mesmerize, Six Decades On Alina Cohen Nov 1, 2019 11:47am Bridget Riley, 1963. Photo by Ida Kar. © National Portrait Gallery, Bridget Riley Blue Dominance, 1977 London. ARCHEUS/POST- MODERN British artist Bridget Riley, who is known for bold, blocky, and striped canvases of brilliant hues and contrasts, got her Drst taste of international celebrity back in 1965. Curator William Seitz included two of her paintings, Current (1964) and Hesitate (1964), in his groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, titled “The Responsive Eye.” The eye-popping black-and-white squiggles of Riley’s Current adorned the catalogue cover, asserting Riley’s prominent position within the show. The exhibition situated her among an impressive roster of global artists whose artwork reconsidered ideas about perception. The group included American painters ranging from Morris Louis to Agnes Martin, along with Brazilian artist Almir da Silva Mavignier and a Spanish collective called Equipo 57. Along with Mavignier, Riley was considered part of a new wave of “Op artists” who exploited visual principles to make work that seemed to vibrate with new energy. Josef Albers, Salvador Dalí, and the museum-going public all swooned at Riley’s work. maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London While Op art has gone in and out of style, Riley herself is still working and is beloved on both sides of the pond. London’s Hayward Gallery is displaying a major Riley retrospective through January 26th, celebrating over six decades of the artist’s bold geometric abstratractions. -

Art Masterpiece: Pisa II, by Al Held Keywords

Art Masterpiece: Pisa II, by Al Held Keywords: Abstract Expressionism, Kinetic Art/Op-Art, Geometric Grade(s): Activity: Optical-Art 3-D hand drawing About the Artist: Al Held, born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 12, 1928. He was a high-school drop-out who joined the Navy and discovered an interest in art. He later became a Professor at Yale University. Held touched on several styles of art from Abstract Expressionism to Op- Art, Illusionism, Minimalism, and Hard Edge. Abstract Expressionism is a style of artwork that is focused on expressing a feeling through the use of color and shape. Held developed his geometric form of abstraction by blending the randomly dripped painting style of Jackson Pollack with the meticulously ordered canvases of Piet Mondrian. Held used straight edges, masking tape and multiple coats of evenly applied paint to create works with intersecting lines, overlapping circles, triangles and other geometric figures. With subtle splashes of color and illusions of Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece Program, Chandler, Arizona, USA three-dimensional depth, the paintings could, in the words of one critic, be "disorienting to the point of vertigo." Busy until the end, Held could command more than $1million for his monumental works. He felt proprietary about his paintings along after completed. He would oversee a team of artists whenever his murals needed touching up. About the Artwork: Pisa II is a work that exemplifies the intersection of math and art. The painting was created during a time when abstract art was gaining prominence all over the world, particularly in America. -

Gce History of Art Major Modern Art Movements

FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS Major Modern Art Movements Key words Overview New types of art; collage, assemblage, kinetic, The range of Major Modern Art Movements is photography, land art, earthworks, performance art. extensive. There are over 100 known art movements and information on a selected range of the better Use of new materials; found objects, ephemeral known art movements in modern times is provided materials, junk, readymades and everyday items. below. The influence of one art movement upon Expressive use of colour particularly in; another can be seen in the definitions as twentieth Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism, century art which became known as a time of ‘isms’. Cubism, Expressionism, and colour field painting. New Techniques; Pointilism, automatic drawing, frottage, action painting, Pop Art, Neo-Impressionism, Synthesism, Kinetic Art, Neo-Dada and Op Art. 1 FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART / MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS The Making of Modern Art The Nine most influential Art Movements to impact Cubism (fl. 1908–14) on Modern Art; Primarily practised in painting and originating (1) Impressionism; in Paris c.1907, Cubism saw artists employing (2) Fauvism; an analytic vision based on fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. It was like a deconstructing of (3) Cubism; the subject and came as a rejection of Renaissance- (4) Futurism; inspired linear perspective and rounded volumes. The two main artists practising Cubism were Pablo (5) Expressionism; Picasso and Georges Braque, in two variants (6) Dada; ‘Analytical Cubism’ and ‘Synthetic Cubism’. This movement was to influence abstract art for the (7) Surrealism; next 50 years with the emergence of the flat (8) Abstract Expressionism; picture plane and an alternative to conventional perspective. -

Bridget Riley Valentine Op Art Heart

Op Art: Lesson Bridget Riley 6 Valentine Op Art Heart • How do 2D geometric shapes invoke movement? • How can the manipulation of geometric shapes and patterns create dimension in 2D art? LESSON OVERVIEW/OBJECTIVES Students will learn about the artist Bridget Riley and her work in Optical Art (Op Art). Riley (1931-present) is a British artist known for bringing about the Op Art movement. Op Art is a style of visual art that uses precise patterns and color to create optical illusions. Op art works are abstract, with many better known pieces created in black and white. Typically, they give the viewer the impression of movement, hidden images, flashing and vibrating patterns, or of swelling or warping. After learning about Bridget Rily and the Op Art movement, students will create an Op Art heart and background for Valentine’s Day. KEY IDEAS THAT CONNECT TO VISUAL ARTS CORE CURRICULUM: Based on Utah State Visual Arts Core Curriculum Requirements (3rd Grade) Strand: CREATE (3.V.CR.) Students will generate artistic work by conceptualizing, organizing, and completing their artistic ideas. They will refine original work through persistence, reflection, and evaluation. Standard 3.V.CR.1: Elaborate on an imaginative idea and apply knowledge of available resources, tools, and technologies to investigate personal ideas through the art-making process. Standard 3.V.CR.2: Create a personally satisfying artwork using a variety of artistic processes and materials. Standard 3.V.CR.3: Demonstrate an understanding of the safe and proficient use of materials, tools and equipment for a variety of artistic processes. -

Op Art Learning Targets

Op Art Learning Targets Students will be able to develop and use criteria to evaluate craftsmanship in an artwork. Students will use elements and principles to organize the composition in his or her own artwork. How will hit these targets? Discuss craftsmanship Review Elements and Principles PowerPoint Presentation Practice drawing Project: Optical Illusion drawing So what is “craftsmanship”? “craftsmanship” skill in a particular craft the quality of design and work shown in something made by hand; artistry “craftsmanship” skill in a particular craft the quality of design and work shown in something made by hand; artistry. Elements and Principles Elements of art: Principles of • Line Design: • Color • Rhythm • Value • Movement • Shape • Pattern • Form • Balance • Texture • Contrast • Space • Emphasis • Unity Optical Illusions Back in 1915, a cartoonist named W.E. Hill first published this drawing. It's hard to see what it's supposed to be. Is it a drawing of a pretty young girl looking away from us? Or is it an older woman looking down at the floor? Optical Illusions Well, it's both. PERCEPTION: a The key is way of regarding, perception and understanding, or what you expect interpreting something; a to see. mental impression Optical Illusions This simple line drawing is titled, "Mother, Father, and daughter" (Fisher, 1968) because it contains the faces of all three people in the title. How many faces can you find? Optical Illusion: something that deceives/confuses the eye/brain by appearing to be other than it is Optical Illusions Optical Art is a mathematically- oriented form of (usually) Abstract art. It uses repetition of simple forms and colors to create vibrating effects, patterns, an exaggerated sense of depth, foreground- background confusion, and other visual effects. -

52 Brook's Mews. Mayfair, W1K 4ED T: 02074953101 E: [email protected]

Press Release Not So Original: Carlos Cruz-Diez, León Ferrari, Terry Frost, Cipriano Martinez, Bridget Riley, Jesus Soto and Emilia Sunyer 8th November – 25th January 2014 This November Maddox Arts will be staging ‘Not So Original’ an exhibition that delves into the symbiotic relationship between the print and the original. Though printmaking is often assumed to be an afterthought in an artist’s practice ‘Not So Original’ demonstrates the variety of roles it may play, spurring the artist’s imagination and engaging in a dialogue with their primary practices. Taking Walter Benjamin’s seminal ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ as it's starting point, ‘Not So Original’ features the work of five, celebrated 20th century printmakers: Bridget Riley, Carlos Cruz-Diaz, Leon Ferrari, Terry Frost and Jesus Soto, alongside the emerging talents of Cipriano Martinez and Emilia Sunyer. From the Middle Ages to the advent of the digital era, technology has allowed artists to disseminate their images in the form of reproductions to a wider audience than a single canvas would ever be able to reach. In facing the prospect of engaging a wider audience artists are often compelled to formalize their style so that a singular print may surmise an artist’s catalogue. Likewise such technologies have enabled art lovers to acquire a ‘piece’ of an original via a process in which the artist may have had no hand. The rise of e-editions and 3D printing ask further questions as to how we distinguish the original from the reproduction, when an infinite number of copies can be instantly and flawlessly reproduced indefinitely. -

Viewership and How These Binaries Function and Appear Within Abstract Painting

Contextualizing Epiphanies and Theories on a Surface of a Painting THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Maija Helena Miettinen-Harris Graduate Program in Art The Ohio State University 2015 Master’s Examination Committee: Laura Lisbon, Advisor George Rush Amanda Gluibizzi Copyright by Maija Helena Miettinen-Harris 2015 Abstract In this thesis I intend to explore the complex, confusing and often paradoxical nature of my painting practice and the way I see it being influenced by historical, socio-political and ideological underpinnings of my reality. During the course of my thesis, I hope to establish a conceptual and contextual basis for my usage of allover pattern-like configurations, rejection of linear perspective, and the manipulation of competing forms and colors in my abstract paintings. I will focus on to the often-elliptical nature of my paintings through variety of ideas and theories and I hope to demonstrate how cultural theory has helped me to contextualize the essential features of my practice. I will first map out the mostly intuitive epiphanies that are rooted in the observations of my reality, which in turn informs the constructions and orientations of my paintings. I will study these in relation to the notions of artist Bridget Riley. I find her writing especially useful in terms of articulating the dichotomy and paradox between active and passive viewership and how these binaries function and appear within abstract painting. I will then examine the circular and expanding theory of liminality by cultural anthropologist Victor Turner, and centers and margins as well as cultural dirt by anthropologist Mary Douglas. -

Bridget Riley Born 1931 in London

This document was updated March 3, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Bridget Riley Born 1931 in London. Live and works in London. EDUCATION 1949-1952 Goldsmiths College, University of London 1952-1956 Royal College of Art, London SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Bridget Riley, Gallery One, London, April–May 1963 Bridget Riley, Gallery One, London, September 9–28 Bridget Riley, University Art Gallery, Nottingham 1965 Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York Bridget Riley, Feigen/Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles 1966 Bridget Riley, Preparatory Drawings and Studies, Robert Fraser Gallery, London, June 8–July 9 Bridget Riley: Drawings, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York 1967 Bridget Riley: Drawings, The Museum of Modern Art (Department of Circulating Exhibitions, USA): Wilmington College, Wilmington, February 12–March 5; and Talladega College, Talladega, March 24–April 16 Bridget Riley, Robert Fraser Gallery, London Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York 1968 Bridget Riley, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York British Pavilion (with Phillip King), XXXIV Venice Biennale, 1968; Städtische Kunstgalerie, Bochum, November 23–December 30, 1968; and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 1969 1969 Bridget Riley, Rowan Gallery, London Bridget Riley: Drawings, Bear Lane Gallery, Oxford [itinerary: Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol; Midland Group Gallery, Nottingham] 1970 Bridget Riley: Prints, Kunststudio, Westfalen-Blatt, Bielefeld Bridget Riley: Paintings and Drawings 1951–71, Arts -

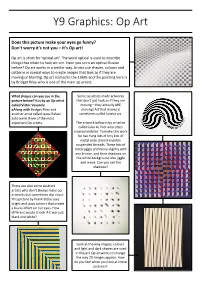

Y9 Graphics: Op Art

Y9 Graphics: Op Art Does this picture make your eyes go funny? Don't worry it's not you – it's Op art! Op art is short for 'optical art'. The word optical is used to describe things that relate to how we see. Have you seen an optical Illusion before? Op art works in a similar way. Artists use shapes, colours and patterns in special ways to create images that look as if they are moving or blurring. Op art started in the 1960s and the painting here is by Bridget Riley who is one of the main op artists. What shapes can you see in the Some op artists made artworks picture below? It is by an Op artist that don't just look as if they are called Victor Vasarely. moving – they actually ARE aAlong with Bridget Riley and moving! Art that moves is another artist called Jesus Rafael sometimes called kinetic art. Soto were three of the most important Op artists. The artwork below is by an artist called Julio Le Parc who often created mobiles. To make this work he has hung lots of tiny bits of metal onto almost invisible suspended threads. These bits of metal jiggle and move slightly with any breeze, and their shadows on the white background also jiggle and move. Can you see the shadows? There are also some abstract artists who don't always make op artworks but sometimes slip into it. This picture by Frank Stella uses bright and jazzy colours that create a buzzy effect on our eyes.