The Experience of Occupation in the Nord, 1914–18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Implodes and Workers Explode in Flanders, 1789-1914

................................................................. CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 . --------- ---- --------------- --- ....................... - ---------- CRSO Working Paper [I296 Copies available through: Center for Research on Social Organization University of Michigan 330 Packard Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 Flanders in 1789 In Lille, on 23 July 1789, the Marechaussee of Flanders interrogated Charles Louis Monique. Monique, a threadmaker and native of Tournai, lived in the lodging house kept by M. Paul. Asked what he had done on the night of 21-22 July, Monique replied that he had spent the night in his lodging house and I' . around 4:30 A.M. he got up and left his room to go to work. Going through the rue des Malades . he saw a lot of tumult around the house of Mr. Martel. People were throwing all the furniture and goods out the window." . Asked where he got the eleven gold -louis, the other money, and the elegant walking stick he was carrying when arrested, he claimed to have found them all on the street, among M. Martel's effects. The police didn't believe his claims. They had him tried immediately, and hanged him the same day (A.M. Lille 14336, 18040). According to the account of that tumultuous night authorized by the Magistracy (city council) of Lille on 8 August, anonymous letters had warned that there would be trouble on 22 July. On the 21st, two members of the Magistracy went to see the comte de Boistelle, provincial military commander; they proposed to form a civic militia. -

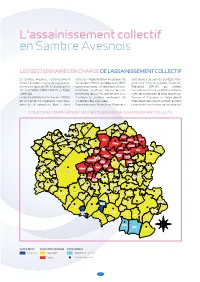

L'assainissement Collectif En Sambre Avesnois

L'assainissement collectif en Sambre Avesnois Les gestionnaires en charge de L’assainissement coLLectif En Sambre Avesnois, l’assainissement partie de l’Agglomération Maubeuge Val sont réunies au sein du Syndicat Inter- collectif est pour une grande majorité des de Sambre (AMVS), qui délègue au SMVS communal d’Assainissement Fourmies- communes (près de 80 %) assuré par le cette compétence. Un règlement d’assai- Wignehies (SIAFW), qui délègue Syndicat Mixte SIDEN-SIAN et sa Régie nissement spécifique s’impose dans les l’assainissement à la société Eau et Force. NOREADE. communes de l’AMVS, permettant ainsi Enfin, les communes de Beaurepaire-sur- SCOTLe Sambre-AvesnoisSyndicat Mixte Val de Sambre (SMVS) d’assurer un meilleur rendement du Sambre et Boulogne sur Helpe gèrent est chargé de la compétence assainisse- traitement des eaux usées. directement leur assainissement en régie Structuresment de compétentes 28 communes, dont et ( 22ou font ) gestionnaires Deux communes, de Fourmies l’assainissement et Wignehies, collectifcommunale, sans passer par un syndicat. structures compétentes et (ou) gestionnaires de L’assainissement coLLectif Houdain- Villers-Sire- lez- Nicole Gussignies Bavay Bettignies Hon- Hergies Gognies- Eth Chaussée Bersillies Vieux-Reng Bettrechies Taisnières- Bellignies sur-Hon Mairieux Bry Jenlain Elesmes Wargnies- La Flamengrie le-Grand Saint-Waast Feignies Jeumont Wargnies- (communeSaint-Waast isolée) Boussois le-Petit Maresches Bavay Assevent Marpent La LonguevilleLa Longueville Maubeuge Villers-Pol Preux-au-Sart (commune -

Prefecture Du Nord Republique Francaise

PREFECTURE DU NORD REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE ---------------------------------- ------------------------------------- DIRECTION DES MOYENS ET DE LA COORDINATION Bureau de la coordination et des affaires immobilières de l'Etat Arrêté portant sur le classement des infrastructures de transports terrestres et l’isolement acoustique des bâtiments d’habitation dans les secteurs affectés par le bruit - Communes de l'arrondissement de Valenciennes - Le Préfet de la Région Nord/Pas-de-Calais Préfet du Nord Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur Vu le code de la construction et de l’habitation, et notamment son article R 111-4-1, Vu le code de l’urbanisme, et notamment ses articles R 123-13 et R 123-14, Vu le code de l’environnement, et notamment son article L 571-10, Vu la loi n°92-1444 du 31 décembre 1992 relative à la lutte contre le bruit, et notamment son article 14, Vu le décret n° 95.20 du 9 janvier 1995 pris pour l’application de l’article L 111-11-1 du code de la construction et de l’habitation et relatif aux caractéristiques acoustiques de certains bâtiments autres que d’habitation et de leurs équipements, Vu le décret n° 95-21 du 9 janvier 1995 relatif au classement des infrastructures de transports terrestres et modifiant le code de l’urbanisme et le code de la construction et de l’habitation, Vu l’arrêté du 9 janvier 1995 relatif à la limitation du bruit dans les établissements d’enseignement, Vu l’arrêté du 30 mai 1996 relatif aux modalités de classement des infrastructures de transports terrestres et à l’isolement acoustique des bâtiments d’habitation dans les secteurs affectés par le bruit, Vu la consultation des communes en date du 27 octobre 1999, A R R E T E : ARTICLE 1 - OBJET Les dispositions de l’arrêté du 30 mai 1996 susvisé sont applicables aux abords du tracé des infrastructures de transports terrestres des communes de l’arrondissement de Valenciennes mentionnées à l’article 2 du présent arrêté. -

Comité De Séquestre Pour La Gestion Des Biens Du Clergé Français Supprimé, Situé Aux Pays-Bas / P

BE-A0510_000433_002911_FRE Inventaire des archives du Comité de Séquestre pour la gestion des biens du clergé français supprimé, situé aux Pays-Bas / P. Lefèvre Het Rijksarchief in België Archives de l'État en Belgique Das Staatsarchiv in Belgien State Archives in Belgium This finding aid is written in French. 2 Comité de Séquestre pour la gestion des biens du clergé français DESCRIPTION DU FONDS D'ARCHIVES:............................................................................5 Consultation et utilisation..............................................................................................6 Recommandations pour l'utilisation................................................................................6 Histoire du producteur et des archives..........................................................................7 Producteur d'archives.......................................................................................................7 Histoire institutionelle/Biographie/Histoire de la famille...........................................7 Compétences et activités.............................................................................................8 Contenu et structure......................................................................................................9 Contenu.............................................................................................................................9 Mode de classement.........................................................................................................9 -

Voirie Départementale Viabilité Hivernale

Voirie Départementale BAISIEUX Viabilité Hivernale Agence Routière de PEVELE-HAINAUT CAMPHIN-EN-PEVELE Barrières de Dégel HIVER COURANT GRUSON WANNEHAIN SAINGHIN-EN-MELANTOIS R D0 093 VENDEVILLE BOUVINES WAVRIN RD0094A HOUPLIN-ANCOISNE R D BOURGHELLES 0 CYSOING 0 6 2 TEMPLEMARS PERONNE-EN-MELANTOIS R D 0 LOUVIL 0 1 A FRETIN 0 9 3 9 SECLIN 9 0 4 0 5 0 0 0 0 D D D R HERRIN R R R GONDECOURT D 3B 0 D009 9 R RD0039 1 7 BACHY 4 R 9 D 0 0 0 R 9 D D AVELIN 1 0 R 06 7 ENNEVELIN RD 2 R 03 COBRIEUX D 45 0 R 1 D 2 0 8 9 ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 5 RD 5 7 0 TEMPLEUVE-EN-PEVELE 4 CHEMY 54 1 9 0 R D D 0 GENECH R R 1 R R D 2 D0 D2 0 8 14 549 5 5 CARNIN 49 5 RD 92 R 009 0 D 3 D 0 R 0 6 PONT-A-MARCQ 2 B R R D D RD 0 0 C 0 549 0 D0054 A ATTICHES R 9 MOUCHIN R 6 D0 62 1 955 0 2 7 R 0 B D D 01 R PHALEMPIN 28 FLINES-LES-MORTAGNE 8 R 0 D 0 CAMPHIN-EN-CAREMBAULT 8 0 0 0 3 R 6 D D 2A 9 R 0 R R 0 D 0 R 4 D MERIGNIES D 0 1 1 D 0 R 6 0 0 6 9 2 1 TOURMIGNIES 0 R 2 NOMAIN D 4 0 5 9 0 CAPPELLE-EN-PEVELE 5 MORTAGNE-DU-NORD 0 0 5 D 2 R 1 0 AIX D 6 2 LA NEUVILLE R 1 7 R 0 032 MAULDE D R D D 0 7 R RD R 2 D 2 127 012 6 01 RD0 7 A 8 0 D RUMEGIES 68 0 R 02 0 A D 8 7 012 R WAHAGNIES 8 D R 3 R D 9 CHATEAU-L'ABBAYE 0 5 0 A 5 D 3 5 4 R 9 9 THUN-SAINT-AMAND 7 0 0 R 0 D A D 6 R D R 4 2 0 95 0954 1 D 0 R D0 MONS-EN-PEVELE RD 0 RUMEGIES 0 HERGNIES 8 R R AUCHY-LEZ-ORCHIES D R 3 2 D 4 BERSEE R R R 6 5 D01 D 8 0 D 58 0 R 0 0 4 LECELLES 2 0 1 27 D 5 5 0 D 8D 0 4 8 6 R SAMEON 6 6 8 6 4 0 0 LECELLES 0 A VIEUX-CONDE D 2 0 D 0 R THUMERIES 2 R R R 1 1 LANDAS 0 D D 9 D R 0 NIVELLE 0 D0 0 008 6 R -

Racines Et Patrimoine En Avesnois Http: Bulletin N°1 Janvier 2011

Bulletin N° 3 de juin 2011 Racines et Patrimoine En Avesnois http:www.rp59.fr Bulletin n°1 Janvier 2011 Le mot du président Notre sixième exposition du jeudi de Tout comme notre week-end portes l’Ascension a attiré, comme tous les ouvertes d’Avril, l’exposition a été l’oc- ans, de nombreux visiteurs. casion de rencontrer de nombreuses personnes intéressées par nos travaux Le beau temps aidant, les abords de d’histoire locale et de généalogie, sim- Rousies étaient occupés par les voitu- ples visiteurs sur les traces de leur res des « bradeux » très tôt le matin. D a n s c e passé, ou passionnés. n u m é r o : Il était donc difficile de trouver un stationnement. Merci à tous les mem- 1 Le mot du bres de l’association qui sont venus président malgré les difficultés. Les outils 1 Les mariages 2 cantonaux Une triste dé- 3 Jean-Pierre BOULEAU et Bernard MARCHAND, lors localisation de l’installation de l’expo Alliance Riche- 4 Potvin La préparation de ces expositions est François Jo- 6 un travail très long; j’en profite pour Photo parue dans « La Voix du Nord » seph Boussus remercier tous ceux qui œuvrent à Les registres 8 Mercredi soir, l’inauguration de l’ex- leurs réalisations. paroissiaux position s’était clôturée par un vin Alain Delfosse Un peintre 9 d’honneur offert par la municipalité. Maubeugeois: Robert Bataille Le bois de 10 Quelques outils à votre disposition Falise Actes curieux 11 Le forum internet Mort pour la 12 http://fr.groups.yahoo.com/group/avesnois/ France La base de données « actes en ligne » Le maquis des 12 Manises http://www.rp59.fr onglet « actes en ligne » Une singulière 14 La table des mariages redevance http://www.rp59.fr onglet « table des mariages » Les Provinces 16 La liste des communes numérisées du Nord http://www.rp59.fr onglet « numérisationse» 2 Les mariages cantonaux La loi du 13 fructidor an VI (jeudi 30 août 1798) décréta que les mariages devaient être célébrés au chef-lieu de district (transformé en chef-lieu de canton), et seulement les décadis. -

Ptuptu -- Principalesprincipales Ligneslignes Dudu Réseauréseau Légende Communes Du Ptu

GRUSON CAMPHIN-EN-PEVELE PTUPTU -- PRINCIPALESPRINCIPALES LIGNESLIGNES DUDU RÉSEAURÉSEAU LÉGENDE COMMUNES DU PTU WANNEHAIN LIGNE A DU TRAMWAY (10') TRANSVILLESTRANSVILLES ARRONDISSEMENTARRONDISSEMENT DEDE VALENCIENNESVALENCIENNES LIGNE DE BUS (20') CYSOING BOURGHELLES LIGNE DE BUS (30') ROYAUME DE BELGIQUE PÔLE D'ÉCHANGE BACHY COBRIEUX GENECH MOUCHIN FLINES-LES-MORTAGNE NOMAIN MORTAGNE 14 AIX MAULDE 14 RUMEGIES CHATEAU THUN -L'ABBAYE HERGNIES AUCHY-LEZ-ORCHIES SAMEON LANDAS LECELLES 64 VIEUX-CONDE NIVELLE ORCHIES BRUILLE-SAINT-AMAND CONDE-SUR-L'ESCAUT ROSULT 12 SAINT-AYBERT BEUVRY-LA-FORET ODOMEZ SARS-ET THIVENCELLE -ROSIERES SAINT-AMAND 14 SAINT-AMAND-LES-EAUX 64 DDTM59 - Direction Départementale des Territoires e Territoires des Départementale Direction - DDTM59 BRILLON BOUVIGNIES FRESNES-SUR-ESCAUT MILLONFOSSE BOUSIGNIES ESCAUTPONT 15 TILLOY-LEZ ESCAUTPONT CRESPIN -MARCHIENNES 16 CRESPIN VICQ HASNON MARCHIENNES WARLAING RAISMES 15 QUAROUBLE t de la Mer du Nord - Délégation Territoriale du Va du Territoriale Délégation - Nord Merdu la de t S2 S1 WANDIGNIES-HAMAGE 13 BRUAY-SUR-L'ESCAUT QUAROUBLE VRED QUIEVRECHAIN 15 RIEULAY BEUVRAGES QUIEVRECHAIN 12 ONNAING 12 16 AUBRY 13 WALLERS ONNAING ERRE -DU-HAINAUT 12 13 15 PECQUENCOURT PETITE-FORET ANZIN VALENCIENNES S2 SAINT-SAULVE ROMBIES 14 SAINT-SAULVE -ET-MARCHIPONT HORNAING FENAIN HORNAING HELESMES BELLAING 16 lenciennois - Prospective, Connaissance Territorial Connaissance Prospective, - lenciennois 15 16 16 SOMAIN HERIN BRUILLE-LEZ -MARCHIENNES HERIN VALENCIENNES ESTREUX HAVELUY OISY 2 -

ARC-EN-CIEL 2020 Schematique A2

vers vers Libercourt 203 206 vers Lille 201 vers Villeneuve d'Ascq vers Valenciennes BREBIERES CORBEHEM COURCHELETTES LAMBRES Lille LEZ DOUAI 207 vers Orchies RÉSEAU D’AUTOCARS DOUAI COROT DES HAUTS-DE-FRANCE 320 325 ABSCON Lycée SECTEUR NORD Polyvalent 6 MariannesEscaudainPlace StadeMarceauClg Félicien1/4 de CitéJoly6 heures HeurteauEgliseCambrésisMerrheimSalle (Forge) BaudinCheminCollège LatéralGare Bayard duErnestine NordDenain311 Hôpital Place Gare de Somain CAMBRÉSIS-SOLESMOIS Cité BonDéchetterie secoursLe ParcPlace Citédes hérosBrisseRésidenceSupermarché MolièreFaconSalle rue du desGrand pont SportsPlace CarréAxter StadeTennisMairieClémenceauSaint-AméLe Châtelier BoulevardRue Pasteur de ParisDe Gaulle Place Carnot Lycée Kästler CAUDRÉSIS-CATÉSIS Edmond Labbé Place ESCAUDAIN HORNAING DENAIN Pont de l'enclos septembre 2020 311 Les Baillons Saint-Pé Rue de Férin 4 Chemins Gare Place 4 Chemins Rond Point 1 Place Bocca Mairie FAMARS UNIVERSITÉ Gare de Douai Delforge Joliot Curie ANICHE 341 EMERCHICOURT SOMAIN Barbusse 303303E 303 333 420 RN vétérinaire Porte de Lycée Église 201 311 DENAIN Monsieur GayantRimbaud MONCHECOURT Collège E Litrée du Raquet FENAIN DOUCHY LES MINES ESPACE VILLARS FAMARS Marbrier VITRY Église BOUCHAIN PLACE ANICHE Mairie Annexe EN ARTOIS DECHY MARCQ EN 340 BOUCHAIN Parrain 311 334 Mineur Mairie COLLÈGE MONOD Maréchal Foch GOUY SOUS DOUAI OSTREVENT Centre Place 341 rue Pasteur NOYELLES SUR SELLE Rue de sailly BELLONNE SIN Église Wignolle LedieuPlace Moulin Cimetière Les 3 Bouleaux Rue Férin LE NOBLE Place Suzanne -

Proces Verbal De La Reunion Du Conseil Municipal Du 28 Septembre 2012

PROCES VERBAL DE LA REUNION DU CONSEIL MUNICIPAL DU 28 SEPTEMBRE 2012 Monsieur le Maire déclare la séance ouverte à 19h10 en présence d'auditeurs. Il souhaite la bienvenue à tous et excuse les absences de Mesdames Véronique PETIT, Christine PLUMECOCQ, Sylvie RATAJCZAK, Béatrice LEVECQUE, Patricia DURIEUX qui ont respectivement donné pouvoir à Madame Evelyne LEGRAND, Monsieur Francis BERKMANS, Monsieur Francis MARIAGE, Madame Sophie CARON et Monsieur Gérard DECHY. Madame Danièle MILLIEZ absente jusqu'à 20h avait donné pouvoir à Madame Claudine LORTHIORS. Le secrétariat de séance est assuré par Madame Francine HAYEZ, Adjointe au Maire. QUESTIONS PREALABLES Monsieur le Maire sollicite l'ajout de 4 points à l'ordre du jour : A. Schéma Départemental de la Coopération Intercommunal (S.D.C.I) – Avis sur le projet du périmètre du futur syndicat intercommunal issu de la fusion du SIARC (Syndicat Intercommunal d'Assainissement de la Région de CONDE-SUR-L'ESCAUT), du SIASEP (Syndicap Intercommunal d'Assainissement de SAULTAIN, ESTREUX et PRESEAU), du SOVIQUA (Syndicat Intercommunal d'Assainissement D'ONNAING, VICQ et QUAROUBLE) et su SIARB – Compétence « ASSAINISSEMENT » (Syndicat Intercommunal d'Aménagement de la Région d'ANZIN, RAISMES, BEUVRAGES, AUBRY DU HAINAUT, PETITE FORET) B. Nouveau projet Résidence « Seniors » - Groupe SIA C. Annulation de la délibération du 28 Janvier 2012 D. Nouveau projet Résidence « Séniors » - Groupe SIA – Acquisitions et cessions foncières Vote : Pour à l'unanimité Monsieur le Maire informe de 5 décisions qu'il a prises dans le cadre de l'article L 2122.22 du Code Général des Collectivités Territoriales. DÉCISION DU 23 JUIN 2012 Le marché « TRAVAUX DE REAMENAGEMENT DES ESPACES PUBLICS – RESIDENCE « LA PASTORALE » est attribué à la Société S.T.B.M 108 bis, Rue Victor Hugo Prolongée – 59860 BRUAY-SUR-ESCAUT. -

REDAC Saint Nord-2015-V2.Indd

DU N S O N R I D A S Le dynamisme au quotidien AGENDA 2015 EDITIONS BUCEREP Cet agenda vous est offert par votre Municipalité interdite même partielle strictement BUCEREP - Reproduction : Editions réalisation et Création Editorial En ces périodes difficiles pour tous, le choix du Conseil Municipal a été de baisser les taux de la Taxe d’Habitation et de la Taxe Foncière sur le Non Bâti. Cet effort est le premier d’une longue liste que le Conseil Municipal va s’imposer (économies à plusieurs niveaux de fonctionnement) sans pour autant diminuer les investissements annoncés. Leur programmation, qui a déjà commencé, s’étalera donc sur les 5 années à venir. Une charge en plus est néanmoins venue impacter de façon conséquente notre budget : c’est l’application de la réforme des rythmes scolaires et tant qu’à appliquer cette réforme, nous avons essayé de faire au mieux de nos possibilités. La volonté du Conseil Municipal a été aussi de pénaliser le moins possible les parents dans leur quotidien, tout en faisant des propositions attractives pour leurs enfants. Un bilan sera tiré de cette action. Vous en serez informés et des adaptations seront toujours possibles. Notre volonté à tous est de faire au mieux et d’être donc, toujours à votre écoute. 2015 Christine Basquin MAIRE DE SAINS DU NORD AGENDA VILLE DE SAINS DU NORD 1 L’équipe municipale Le maire Mme Christine BASQUIN a été réélue Maire. L’équipe muni- cipale se compose comme suit : Les adjoints au maire Jean-Pierre DESSAINT : 1er adjoint, chargé des relations avec les commerçants, les artisans, les entreprises et l’intercommunalité ; de l’organisation de la cérémonie des vœux du maire et des cérémonies patriotiques. -

LISTE-DES-ELECTEURS.Pdf

CIVILITE NOM PRENOM ADRESSE CP VILLE N° Ordinal MADAME ABBAR AMAL 830 A RUE JEAN JAURES 59156 LOURCHES 62678 MADAME ABDELMOUMEN INES 257 RUE PIERRE LEGRAND 59000 LILLE 106378 MADAME ABDELMOUMENE LOUISA 144 RUE D'ARRAS 59000 LILLE 110898 MONSIEUR ABU IBIEH LUTFI 11 RUE DES INGERS 07500 TOURNAI 119015 MONSIEUR ADAMIAK LUDOVIC 117 AVENUE DE DUNKERQUE 59000 LILLE 80384 MONSIEUR ADENIS NICOLAS 42 RUE DU BUISSON 59000 LILLE 101388 MONSIEUR ADIASSE RENE 3 RUE DE WALINCOURT 59830 WANNEHAIN 76027 MONSIEUR ADIGARD LUCAS 53 RUE DE LA STATION 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 116892 MONSIEUR ADONEL GREGORY 84 AVENUE DE LA LIBERATION 59300 AULNOY LEZ VALENCIENNES 12934 CRF L'ESPOIR DE LILLE HELLEMMES 25 BOULEVARD PAVE DU MONSIEUR ADURRIAGA XIMUN 59260 LILLE 119230 MOULIN BP 1 MADAME AELVOET LAURENCE CLINIQUE DU CROISE LAROCHE 199 RUE DE LA RIANDERIE 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 43822 MONSIEUR AFCHAIN JEAN-MARIE 43 RUE ALBERT SAMAIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35417 MADAME AFCHAIN JACQUELINE 267 ALLEE CHARDIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35416 MADAME AGAG ELODIE 137 RUE PASTEUR 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 71682 MADAME AGIL CELINE 39 RUE DU PREAVIN LA MOTTE AU BOIS 59190 MORBECQUE 89403 MADAME AGNELLO SYLVIE 77 RUE DU PEUPLE BELGE 07340 colfontaine 55083 MONSIEUR AGNELLO CATALDO Centre L'ADAPT 121 ROUTE DE SOLESMES BP 401 59407 CAMBRAI CEDEX 55082 MONSIEUR AGOSTINELLI TONI 63 RUE DE LA CHAUSSEE BRUNEHAUT 59750 FEIGNIES 115348 MONSIEUR AGUILAR BARTHELEMY 9 RUE LAMARTINE 59280 ARMENTIERES 111851 MONSIEUR AHODEGNON DODEME 2 RUELLE DEDALE 1348 LOUVAIN LA NEUVE - Belgique121345 MONSIEUR -

Rapport De Visite De L'hôtel De Police De Douai

Hôtel de police de Douai (Nord) Le 30 août 2011 RAPPORT DE VISITE: Hôtel de police de Douai (59) (59) Douai police de de Hôtel DEVISITE: RAPPORT Contrôleurs : - Jacques Gombert , chef de mission ; - Betty Brahmy, - Michel Jouannot. 2 1 CONDITIONS DE LA VISITE En application de la loi du 30 octobre 2007 qui a institué le Contrôleur général des lieux de privation de liberté, trois contrôleurs ont effectué une visite inopinée des locaux de garde à vue de l’hôtel de police de Douai (Nord). Les contrôleurs sont arrivés à l’hôtel de police, situé 150 rue Saint-Sulpice à Douai, le mardi 30 août 2011 à 9h20. Ils en sont repartis le jour même à 17h45. Ils ont été accueillis par le commissaire de police, commissaire central, chef de la circonscription de sécurité publique de Douai agglomération. Une présentation du service a été faite par le commissaire central et par le commandant à l’échelon fonctionnel, adjoint au chef de service de sécurité de proximité. La visite et les entretiens se sont déroulés dans un climat de confiance, avec une réelle volonté de transparence. La qualité de l’accueil doit être soulignée. Une réunion de fin de visite s’est tenue avec le commissaire central. Les contrôleurs ont visité l’ensemble des locaux de privation de liberté de l’hôtel de police : • neuf cellules de garde à vue, dont l’une est plus spécifiquement réservée aux mineurs ; • trois cellules de dégrisement ; • un local servant à la fois aux consultations des médecins et aux entretiens avec les avocats ; • un local de signalisation situé dans la zone des geôles; • les bureaux servant de locaux d’audition.