The Cracked Colonial Foundations of a Neo-Colonial Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

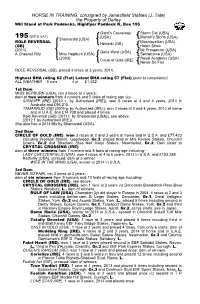

J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195 Giant's Causeway Storm Cat (USA) 195 (WITH VAT) (USA) Mariah's Storm (USA) Shamardal (USA) ROLE REVERSA L Machiavellian (USA) Helsinki (GB) (GB) Helen Street (2011) Mr Prospector (USA) Gone West (USA) A Chesnut Filly Miss Hepburn (USA) Secrettame (USA) (2003) Royal Academy (USA) Circle of Gold (IRE) Never So Fair ROLE REVERSAL (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 62 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 57 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 5 runs 4 pl £1,532 1st Dam MISS HEPBURN (USA), ran 3 times at 2 years; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SIGNOFF (IRE) (2010 c. by Authorized (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years, 2014 in Australia and £96,215. TAMARRUD (GB) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2013 at home and in U.A.E. and £14,738 and placed 4 times. Role Reversal (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), see above. (2012 f. by Authorized (IRE)). She also has a 2013 filly by Shamardal (USA). 2nd Dam CIRCLE OF GOLD (IRE) , won 3 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £77,423 including Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 , placed third in Mrs Revere Stakes, Churchill Downs, Gr.2 and Shadwell Stud Nell Gwyn Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3 ; Own sister to CRYSTAL CROSSING (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- LADY CHESTERFIELD (USA) , won 4 races at 4 to 6 years, 2013 in U.S.A. -

Robotic Grasping and Manipulation

Chapter 1 Robotic Grasping and Manipulation In this chapter, we consider problems that arise in designing, building, planning, and controlling operations of robotic hands and end–effectors. The purpose of such devices is often manifold, and it typically includes grasping and fine manipulation of ojects in an accurate, delicate yet firm way. We survey the state-of-the-art reached by scientific research and literature about the problems engendered by these often conflicting requirements, and the work that has been done in this area over the last two decades. Because of space limitations, the chapter does not attempt at providing a survey of the technology of robot hands, but rather it is oriented towards covering the theoretical framework, analytical results, and open problems in robotic manipulation. 1.1 Introduction In many roboticists, the admiration for what nature accomplishes in everiday’s functions of human beings and animals is the original stimulus for their research in emulating these capabilities in artificial life. Among the many awesome realizations of nature, few of the human abilities distinguish man from animals as deeply as manipulation and speech. Indeed, there are animals that can see, hear, walk, swim, etc. more effcicently than men - but language and manipulation skills are peculiar of our race, and constitute a continuing source of amazement for scientists. In this chapter, we will consider in detail the implementation of artificial systems to replicate in part the manipulating ability of the human hand. The three most important functions of the human hand are to explore, to restrain, and to precisely move objects. -

International Law Enforcement Cooperation in the Fisheries Sector: a Guide for Law Enforcement Practitioners

International Law Enforcement Cooperation in the Fisheries Sector: A Guide for Law Enforcement Practitioners FOREWORD Fisheries around the world have been suffering increasingly from illegal exploitation, which undermines the sustainability of marine living resources and threatens food security, as well as the economic, social and political stability of coastal states. The illegal exploitation of marine living resources includes not only fisheries crime, but also connected crimes to the fisheries sector, such as corruption, money laundering, fraud, human or drug trafficking. These crimes have been identified by INTERPOL and its partners as transnational in nature and involving organized criminal networks. Given the complexity of these crimes and the fact that they occur across the supply chains of several countries, international police cooperation and coordination between countries and agencies is absolutely essential to effectively tackle such illegal activities. As the world’s largest police organization, INTERPOL’s role is to foster international police cooperation and coordination, as well as to ensure that police around the world have access to the tools and services to effectively tackle these transnational crimes. More specifically, INTERPOL’s Environmental Security Programme (ENS) is dedicated to addressing environmental crime, such as fisheries crimes and associated crimes. Its mission is to assist our member countries in the effective enforcement of national, regional and international environmental law and treaties, creating coherent international law enforcement collaboration and enhancing investigative support of environmental crime cases. It is in this context, that ENS – Global Fisheries Enforcement team identified the need to develop a Guide to assist in the understanding of international law enforcement cooperation in the fisheries sector, especially following several transnational fisheries enforcement cases in which INTERPOL was involved. -

Fundamentals of Remote Sensing

Fundamentals of Remote Sensing A Canada Centre for Remote Sensing Remote Sensing Tutorial Natural Resources Ressources naturelles Canada Canada Fundamentals of Remote Sensing - Table of Contents Page 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 What is Remote Sensing? 5 1.2 Electromagnetic Radiation 7 1.3 Electromagnetic Spectrum 9 1.4 Interactions with the Atmosphere 12 1.5 Radiation - Target 16 1.6 Passive vs. Active Sensing 19 1.7 Characteristics of Images 20 1.8 Endnotes 22 Did You Know 23 Whiz Quiz and Answers 27 2. Sensors 2.1 On the Ground, In the Air, In Space 34 2.2 Satellite Characteristics 36 2.3 Pixel Size, and Scale 39 2.4 Spectral Resolution 41 2.5 Radiometric Resolution 43 2.6 Temporal Resolution 44 2.7 Cameras and Aerial Photography 45 2.8 Multispectral Scanning 48 2.9 Thermal Imaging 50 2.10 Geometric Distortion 52 2.11 Weather Satellites 54 2.12 Land Observation Satellites 60 2.13 Marine Observation Satellites 67 2.14 Other Sensors 70 2.15 Data Reception 72 2.16 Endnotes 74 Did You Know 75 Whiz Quiz and Answers 83 Canada Centre for Remote Sensing Fundamentals of Remote Sensing - Table of Contents Page 3 3. Microwaves 3.1 Introduction 92 3.2 Radar Basic 96 3.3 Viewing Geometry & Spatial Resolution 99 3.4 Image distortion 102 3.5 Target interaction 106 3.6 Image Properties 110 3.7 Advanced Applications 114 3.8 Polarimetry 117 3.9 Airborne vs Spaceborne 123 3.10 Airborne & Spaceborne Systems 125 3.11 Endnotes 129 Did You Know 131 Whiz Quiz and Answers 135 4. -

Defining Music As an Emotional Catalyst Through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2011 All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Therapy Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Trier-Bieniek, Adrienne M., "All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture" (2011). Dissertations. 328. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/328 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE. by Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Advisor: Angela M. Moe, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2011 "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation, '"All I Am': Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture", is based in the sociology of emotions, gender and culture and guided by symbolic interactionist and feminist standpoint theory. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8 5 9 5 10

NAKAYAMA SUNDAY,OCTOBER 4TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1200m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:6Dec.09 1:10.2 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Tomoyuki Nakamura 770,000 S 20002 Life40004M 20002 1 1 B 55.0 Yuichiro Nishida(0.8%,1−2−4−121,133rd) Turf40004 I 00000 Maradona(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 .Pelusa(0.05) .Kane Hekili C2,ch. Takaki Iwato(4.9%,11−20−10−183,113rd) Course00000E 00000 Wht. /Maradona Spin /Bambina Coco 23Feb.18 Bamboo Stud Wet 00000 2Aug.20 NIIGATA MDN T1200Fi 11 13 1:11.8 18th/18 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468' Nishino Adjust 1:10.1 <3/4> Tosen Gaia <1/2> Meiner Amistad 19Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1200Fi 7 6 1:11.3 4th/11 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468% Seiun Deimos 1:10.2 <2 1/2> Longing Birth <4> High Priestess 5Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1800Yi 45310 1:54.0 11th/11 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466' Cosmo Ashura 1:50.2 <NK> Magical Stage <NK> Seiun Gold 20Jun.20 TOKYO NWC T1400Go 4 4 1:24.9 7th/16 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466* Cool Cat 1:23.4 <2> Songline <1 1/4> Bisboccia Ow. Toshio Isobe 0 S 20002 Life20002M 00000 1 2 53.0 Akira Sugawara(4.5%,18−25−31−324,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 Isoei Hikari(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 .A Shin Hikari(0.54) .South Vigorous C2,b. -

The Ethical Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness

Marquette Law Review Volume 99 Article 4 Issue 2 Winter 2015 The thicE al Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness: How Modern Ethics Rules Fail to Prevent Truthful Witnesses from Being Discredited Through Unethical Means Todd A. Berger Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Courts Commons, and the Evidence Commons Repository Citation Todd A. Berger, The Ethical Limits of Discrediting the Truthful Witness: How Modern Ethics Rules Fail to Prevent Truthful Witnesses from Being Discredited Through Unethical Means, 99 Marq. L. Rev. 283 (2015). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol99/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETHICAL LIMITS OF DISCREDITING THE TRUTHFUL WITNESS: HOW MODERN ETHICS RULES FAIL TO PREVENT TRUTHFUL WITNESSES FROM BEING DISCREDITED THROUGH UNETHICAL MEANS TODD A. BERGER* Whether the criminal defense attorney may ethically discredit the truthful witness on cross-examination and later during closing argument has long been an area of controversy in legal ethics. The vast majority of scholarly discussion on this important ethical dilemma has examined it in the abstract, focusing on the defense attorney’s dual roles in a criminal justice system that is dedicated to searching for the truth while simultaneously requiring zealous advocacy even for the guiltiest of defendants. Unlike these previous works, this particular Article explores this dilemma from the perspective of the techniques that criminal defense attorney’s use on cross-examination and closing argument to cast doubt on the testimony of a credible witness. -

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., Ph.D. – C.V

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., PH.D. (203) 809-8500 • ZACHARY . KAUFMAN @ AYA . YALE. EDU • WEBSITE • SSRN ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS SCHOOL OF LAW (Jan. – May 2022) Visiting Associate Professor of Law UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LAW CENTER (July 2019 – present) Associate Professor of Law and Political Science (July 2019 – present) Co-Director, Criminal Justice Institute (Aug. 2021 – present) Affiliated Faculty Member: • University of Houston Law Center – Initiative on Global Law and Policy for the Americas • University of Houston Department of Political Science • University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs • University of Houston Elizabeth D. Rockwell Center on Ethics and Leadership STANFORD LAW SCHOOL (Sept. 2017 – June 2019) Lecturer in Law and Fellow EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD – D.Phil. (Ph.D.), 2012; M.Phil., 2004 – International Relations • Marshall Scholar • Doctoral Dissertation: From Nuremberg to The Hague: United States Policy on Transitional Justice o Passed “Without Revisions”: highest possible evaluation awarded o Examiners: Professors William Schabas and Yuen Foong Khong o Supervisors: Professors Jennifer Welsh (primary) and Henry Shue (secondary) o Adaptation published (under revised title) by Oxford University Press • Master’s Thesis: Explaining the United States Policy to Prosecute Rwandan Génocidaires YALE LAW SCHOOL – J.D., 2009 • Editor-in-Chief, Yale Law & Policy Review • Managing Editor, Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal • Articles Editor, Yale Journal of International Law -

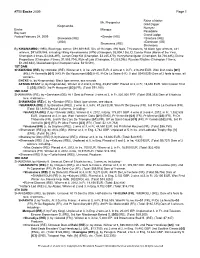

750 Encke 2009 Page 1

#750 Encke 2009 Page 1 Raise a Native Mr. Prospector Gold Digger Kingmambo Nureyev Encke Miesque Pasadoble Bay Colt Grand Lodge Foaled February 24, 2009 =Sinndar (IRE) Shawanda (IRE) =Sinntara (IRE) (2002) =Darshaan (GB) Shamawna (IRE) Shamsana By KINGMAMBO (1990), Black type winner, $91,608,945. Sire of 16 crops. 892 foals, 718 starters, 84 black type winners, 441 winners, $91,608,945, including =King Kamehameha (JPN) (Champion, $3,904,136), El Condor Pasa (Horse of the Year, Champion 3 times, $3,468,397), Lemon Drop Kid (Champion, $3,245,370), Henrythenavigator (Champion, $2,746,485), Divine Proportions (Champion 3 times, $1,553,704), Rule of Law (Champion, $1,323,096), Russian Rhythm (Champion 3 times, $1,260,634), Walzerkoenigin (Champion twice, $410,591). 1ST DAM SHAWANDA (IRE), by =Sinndar (IRE). Winner at 3, in Ire, 225,200 EUR. 4 wins at 3, in Fr, 216,450 EUR. Won Irish Oaks [G1] (IRE), Pr Vermeille [G1] (FR), Pr De Royaumont [G3] (FR), Pr De La Seine (FR). (Total: $540,029) Dam of 2 foals to race, all winners-- ENCKE (c, by Kingmambo). Black type winner, see records. GENIUS BEAST (c, by Kingmambo). Winner at 2 and 3, in Eng, 43,857 GBP. Placed at 3, in Fr, 13,650 EUR. Won Classic Trial S. [G3] (ENG). 3rd Pr Hocquart [G2] (FR). (Total: $91,160) 2ND DAM SHAMAWNA (IRE), by =Darshaan (GB). At 1 Sent to France. 2 wins at 3, in Fr, 220,000 FRF. (Total: $39,393) Dam of 6 foals to race, 4 winners-- SHAWANDA (IRE) (f, by =Sinndar (IRE)). -

FIVE DIAMONDS Barn 2 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Three Chimneys Sales, Agent Barn Hip No. 2 FIVE DIAMONDS 1 Dark Bay or Brown Mare; foaled 2006 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy............................ Weekend Surprise Flatter................................ Mr. Prospector Praise................................ Wild Applause FIVE DIAMONDS Cyane Smarten ............................ Smartaire Smart Jane........................ (1993) *Vaguely Noble Synclinal........................... Hippodamia By FLATTER (1999). Black-type-placed winner of $148,815, 3rd Washington Park H. [G2] (AP, $44,000). Sire of 4 crops of racing age, 243 foals, 178 starters, 11 black-type winners, 130 winners of 382 races and earning $8,482,994, including Tar Heel Mom ($472,192, Distaff H. [G2] (AQU, $90,000), etc.), Apart ($469,878, Super Derby [G2] (LAD, $300,000), etc.), Mad Flatter ($231,488, Spend a Buck H. [G3] (CRC, $59,520), etc.), Single Solution [G3] (4 wins, $185,039), Jack o' Lantern [G3] ($83,240). 1st dam SMART JANE, by Smarten. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $61,656. Dam of 7 registered foals, 7 of racing age, 7 to race, 5 winners, including-- FIVE DIAMONDS (f. by Flatter). Black-type winner, see record. Smart Tori (f. by Tenpins). 5 wins at 2 and 3, 2010, $109,321, 3rd Tri-State Futurity-R (CT, $7,159). 2nd dam SYNCLINAL, by *Vaguely Noble. Unraced. Half-sister to GLOBE, HOYA, Foamflower, Balance. Dam of 6 foals to race, 5 winners, including-- Taroz. Winner at 3 and 4, $26,640. Sent to Argentina. Dam of 2 winners, incl.-- TAP (f. by Mari's Book). 10 wins, 2 to 6, 172,990 pesos, in Argentina, Ocurrencia [G2], Venezuela [G2], Condesa [G3], General Lavalle [G3], Guillermo Paats [G3], Mexico [G3], General Francisco B. -

Legacy-Project-Full.Pdf

ÉTHE MUSIC WORLD IS STILL THE MOST INNOVATIVE, ENERGIZING, AND ECLECTIC SLICE OF THE AMERICAN- POP-CULTURE PIE. BUT WHAT ARTISTS SHOULD A MAN ACTUALLY BE LISTENING TO RIGHT NOW? AND WHO WILL WE STILL BE LISTENING TO TEN, TWENTY, AND EVEN FIFTY YEARS FROM NOW? AS THE 2015 GRAMMYS APPROACH, WE TAKE A LOOK AT THE MUSIC MAKERS WHO, THIS YEAR, LEFT SOMETHING LASTING BEHIND THE LEGACY PROJECT PORTFOLIO PARI DUKOVIC 02.15 GQ. COM 51 PHARRELL WILLIAMS THE MAN WHO NEVER SLEEPS Photographed at Mr. C hotel in Beverly Hills. Thirteen Hours Inside Pharrell Williams’s Relentless Pop- Culture Machine BY DEVIN FRIEDMAN 10:57 a.m. Uniqlo, West Hollywood WHEN PHARRELL arrives, it’s as if in a bubble. Like Glenda, the Good Witch of the North. Starbucks in one hand, two Asian-American women assistants trailing in his wake, a Chanel scarf waving from his back pocket. Uniqlo has closed this store, in the Beverly Center, for an event: About thirty homeless kids have been given a shopping spree. Pharrell Williams, who of course collaborates on a clothing line with Uniqlo, is the surprise guest. He takes a picture with a girl in a her royal smurfness T-shirt and checks out jeans with a kid in a Lakers jersey. Truth be told, a lot of these kids don’t seem to know who he is. Most 7-year-olds don’t even know what a celebrity is. They don’t know that this is the man who, not long ago, was responsible for 43 percent of songs played on the radio in a single month; they probably don’t watch The Voice, where Pharrell is a celebrity “coach”; they don’t listen to “Blurred Lines” and know, hey, the genius behind that song wasn’t Robin Thicke, it was longtime super-producer and current pop star Pharrell Williams; and they don’t know that his 2014 album, Girl, is up for an album- of-the-year Grammy.