Pasts, Presents, and a Possible Future.1 Martin Krygier the Rule of Law Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cracked Colonial Foundations of a Neo-Colonial Constitution

1 THE CRACKED COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS OF A NEO-COLONIAL CONSTITUTION Klearchos A. Kyriakides This working paper is based on a presentation delivered at an academic event held on 18 November 2020, organised by the School of Law of UCLan Cyprus and entitled ‘60 years on from 1960: A Symposium to mark the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus’. The contents of this working paper represent work in progress with a view to formal publication at a later date.1 A photograph of the Press and Information Office, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of Cyprus, as reproduced on the Official Twitter account of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus, 16 August 2018, https://twitter.com/cyprusmfa/status/1030018305426432000 ©️ Klearchos A. Kyriakides, Larnaca, 27 November 2020 1 This working paper reproduces or otherwise contains Crown Copyright materials and other public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0, details of which may be viewed on the website of the National Archives of the UK, Kew Gardens, Surrey, at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernment-licence/version/3/ This working paper also reproduces or otherwise contains British Parliamentary Copyright material and other Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence, details of which may be viewed on the website of the Parliament of the UK at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/ 2 Introduction This working paper has one aim. It is to advance a thesis which flows from a formidable body of evidence. At the moment when the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus (‘the 1960 Constitution’) came into force in the English language at around midnight on 16 August 1960, it stood on British colonial foundations, which were cracked and, thus, defective. -

Social Studies –American History: the Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course

Appendix A: American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics This appendix contains additions made to the North Carolina Essential Standards for Civics and Economics pursuant to the North Carolina General Assembly passage of The Founding Principles Act (SL 2011-273). This document is organized as follows: an introduction that describes the intent of the course and a set of standards that establishes the expectation of what students should understand, know, and be able to do upon successful completion of the course. There are ten essential standards for this course, each with more specific clarifying objectives. The name of the course has been changed to American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics and the last column has been added to show the alignment of the standards to the Founding Principles Act. 6 North Carolina Essential Standards Social Studies –American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics has been developed as a course that provides a framework for understanding the basic tenets of American democracy, practices of American government as established by the United States Constitution, basic concepts of American politics and citizenship and concepts in macro and micro economics and personal finance. The essential standards of this course are organized under three strands – Civics and Government, Personal Financial Literacy and Economics. The Civics and Government strand is framed to develop students’ increased understanding of the institutions of constitutional democracy and the fundamental principles and values upon which they are founded, the skills necessary to participate as effective and responsible citizens and the knowledge of how to use democratic procedures for making decisions and managing conflict. -

The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry 1

Running Head: THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 1 The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry Learning Strategies and Logical Thinking Ability towards Learning of Civics in Senior High School (SMA) 1Hernawaty Damanik 2I Nyoman S. Degeng 2Punaji Setyosari 2I Wayan Dasna 1Open University; State University of Malang 2State University of Malang Author Note Hernawaty Damanik is senior lecturer at Open University, Malang, and student of Graduate Program in Education Technology State University of Malang. I Nyoman S. Degeng and Punaji Setyosari are professors at Graduate Program State University of Malang. I Wayan Dasna is senior lecturer at Graduate Program State University of Malang Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to [email protected] THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 2 THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY LEARNING STRATEGIES AND LOGICAL THINKING ABILITY TOWARDS LEARNING OF CIVICS SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL (SMA) Abstract Pancasila and Citizenship Education (Civics) is one of many other school subjects emphasizing on value and moral education in order to form multicultural Indonesian citizens who appreciate the culture of plural communities. The learning of PPKn (civics) should be designed and developed through a thorough strategy in accordance with its aims and materials to create students with critical, argumentative, and logical thinking ability. The learning of civics has not been totally carried out on the tract where teachers are dominantly active in the class while students just do memorizing and reading, less of joyfull learning, and become “text-bookish”. One of many other strategies to succeed innovative, constructive, and relevant learning in accordance with the thinking ability of Senior High School students is through jurisprudential inquiry. -

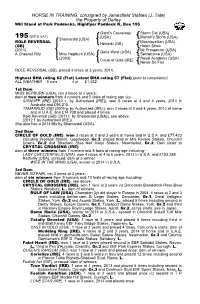

J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195 Giant's Causeway Storm Cat (USA) 195 (WITH VAT) (USA) Mariah's Storm (USA) Shamardal (USA) ROLE REVERSA L Machiavellian (USA) Helsinki (GB) (GB) Helen Street (2011) Mr Prospector (USA) Gone West (USA) A Chesnut Filly Miss Hepburn (USA) Secrettame (USA) (2003) Royal Academy (USA) Circle of Gold (IRE) Never So Fair ROLE REVERSAL (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 62 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 57 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 5 runs 4 pl £1,532 1st Dam MISS HEPBURN (USA), ran 3 times at 2 years; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SIGNOFF (IRE) (2010 c. by Authorized (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years, 2014 in Australia and £96,215. TAMARRUD (GB) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2013 at home and in U.A.E. and £14,738 and placed 4 times. Role Reversal (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), see above. (2012 f. by Authorized (IRE)). She also has a 2013 filly by Shamardal (USA). 2nd Dam CIRCLE OF GOLD (IRE) , won 3 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £77,423 including Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 , placed third in Mrs Revere Stakes, Churchill Downs, Gr.2 and Shadwell Stud Nell Gwyn Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3 ; Own sister to CRYSTAL CROSSING (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- LADY CHESTERFIELD (USA) , won 4 races at 4 to 6 years, 2013 in U.S.A. -

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test M-638 (rev. 02/19) Learn About the United States: Quick Civics Lessons Thank you for your interest in becoming a citizen of the United States of America. Your decision to apply for IMPORTANT NOTE: On the naturalization test, some U.S. citizenship is a very meaningful demonstration of answers may change because of elections or appointments. your commitment to this country. As you study for the test, make sure that you know the As you prepare for U.S. citizenship, Learn About the United most current answers to these questions. Answer these States: Quick Civics Lessons will help you study for the civics questions with the name of the official who is serving and English portions of the naturalization interview. at the time of your eligibility interview with USCIS. The USCIS Officer will not accept an incorrect answer. There are 100 civics (history and government) questions on the naturalization test. During your naturalization interview, you will be asked up to 10 questions from the list of 100 questions. You must answer correctly 6 of the 10 questions to pass the civics test. More Resources to Help You Study Applicants who are age 65 or older and have been a permanent resident for at least 20 years at the time of Visit the USCIS Citizenship Resource Center at filing the Form N-400, Application for Naturalization, uscis.gov/citizenship to find additional educational are only required to study 20 of the 100 civics test materials. Be sure to look for these helpful study questions for the naturalization test. -

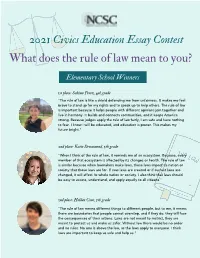

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

"Public Service Must Begin at Home": the Lawyer As Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 50 (2008-2009) Issue 4 The Citizen Lawyer Symposium Article 5 3-1-2009 "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice Bruce A. Green Russell G. Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Bruce A. Green and Russell G. Pearce, "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice, 50 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1207 (2009), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol50/iss4/5 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr "PUBLIC SERVICE MUST BEGIN AT HOME": THE LAWYER AS CIVICS TEACHER IN EVERYDAY PRACTICE BRUCE A. GREEN* & RUSSELL G. PEARCE** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1208 I. THE IDEA OF THE LAWYER AS Civics TEACHER ........... 1213 II. WHY LAWYERS SHOULD TEACH CIVICS WELL ........... 1219 A. Teaching Civics Well as a Public Service ............ 1220 B. Teaching Civics Well as Intrinsic to the Lawyer's Social Function ......................... 1223 1. The ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers' PedagogicRole as Derived from Their Social Function .......................... 1223 2. Antecedents to the ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ........................ 1227 3. The Perpetuationof the ABA/AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ................. 1231 III. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CONCEPT IN PROFESSIONAL AND ACADEMIC DISCOURSE ............. 1233 A. Serving the Public Good ......................... 1233 B. The Lawyer's Role in a Democracy ................ -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8 5 9 5 10

NAKAYAMA SUNDAY,OCTOBER 4TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1200m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:6Dec.09 1:10.2 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Tomoyuki Nakamura 770,000 S 20002 Life40004M 20002 1 1 B 55.0 Yuichiro Nishida(0.8%,1−2−4−121,133rd) Turf40004 I 00000 Maradona(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 .Pelusa(0.05) .Kane Hekili C2,ch. Takaki Iwato(4.9%,11−20−10−183,113rd) Course00000E 00000 Wht. /Maradona Spin /Bambina Coco 23Feb.18 Bamboo Stud Wet 00000 2Aug.20 NIIGATA MDN T1200Fi 11 13 1:11.8 18th/18 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468' Nishino Adjust 1:10.1 <3/4> Tosen Gaia <1/2> Meiner Amistad 19Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1200Fi 7 6 1:11.3 4th/11 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468% Seiun Deimos 1:10.2 <2 1/2> Longing Birth <4> High Priestess 5Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1800Yi 45310 1:54.0 11th/11 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466' Cosmo Ashura 1:50.2 <NK> Magical Stage <NK> Seiun Gold 20Jun.20 TOKYO NWC T1400Go 4 4 1:24.9 7th/16 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466* Cool Cat 1:23.4 <2> Songline <1 1/4> Bisboccia Ow. Toshio Isobe 0 S 20002 Life20002M 00000 1 2 53.0 Akira Sugawara(4.5%,18−25−31−324,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 Isoei Hikari(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 .A Shin Hikari(0.54) .South Vigorous C2,b. -

Civics and Economics CE.6 Study Guide

HISTORY AND SOCIAL SCIENCE STANDARDS OF LEARNING • Prepares the annual budget for congressional action CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK 2008 (NEW) Reformatted version created by SOLpass • Appoints cabinet officers, ambassadors, and federal judges www.solpass.org Civics and Economics • Administers the federal bureaucracy The judicial branch CE.6 Study Guide • Consists of the federal courts, including the Supreme Court, the highest court in the land • The Supreme Court exercises the power of judicial review. • The federal courts try cases involving federal law and questions involving interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. STANDARD CE.6A -- NATIONAL GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE The structure and powers of the national government. The Constitution of the United States defines the structure and powers of the national government. The powers held by government are divided between the national government in Washington, D.C., and the governments of the 50 states. What is the structure of the national government as set out in the United States Constitution? STANDARD CE.6B What are the powers of the national government? -- SEPARATION OF POWERS Legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the national government are distributed among three distinct and independent branches of government. The principle of separation of powers and the operation of checks and balances. The legislative branch • Consists of the Congress, a bicameral legislature The powers of the national government are separated consisting of the House of Representatives (435 among three -

Final Report of the Committee to Study the Scope And

STATE OF MAINE 121ST LEGISLATURE FIRST REGULAR SESSION Final Report of the Commission to Study the Scope and Quality of Citizenship Education February 2004 Members: Senator Neria R. Douglas, Chair Representative Glenn Cummings, Chair Senator Betty Lou Mitchell Representative Gerald M. Davis Joseph Burnham Gale Caddoo Amanda Coffin Staff: Christopher J. Hall Phillip D. McCarthy, Ed.D., Legislative Analyst Judith Harvey Nicole A. Dube, Legislative Analyst Kurt Hoffman Richard Marchi Office of Policy & Legal Analysis Denise O’Toole Maine Legislature Elizabeth McCabe Park (207) 287-1670 Patrick Phillips http://www.state.me.us/legis/opla/ Francine Rudoff Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i I. Introduction....................................................................................................... 1 II. Background ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Summary of Key Findings ................................................................................ 8 IV. Conclusions and Recommendations ............................................................... 15 Appendices A. Authorizing Legislation, Resolve 2003, Chapter 85 B. Membership List, Commission to Study the Scope and Quality of Citizenship Education C. Resource People and Presenters Providing Information to the Commission D. Definitions E. Bibliography of Citizenship Education Materials F. Citizenship -

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., Ph.D. – C.V

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., PH.D. (203) 809-8500 • ZACHARY . KAUFMAN @ AYA . YALE. EDU • WEBSITE • SSRN ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS SCHOOL OF LAW (Jan. – May 2022) Visiting Associate Professor of Law UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LAW CENTER (July 2019 – present) Associate Professor of Law and Political Science (July 2019 – present) Co-Director, Criminal Justice Institute (Aug. 2021 – present) Affiliated Faculty Member: • University of Houston Law Center – Initiative on Global Law and Policy for the Americas • University of Houston Department of Political Science • University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs • University of Houston Elizabeth D. Rockwell Center on Ethics and Leadership STANFORD LAW SCHOOL (Sept. 2017 – June 2019) Lecturer in Law and Fellow EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD – D.Phil. (Ph.D.), 2012; M.Phil., 2004 – International Relations • Marshall Scholar • Doctoral Dissertation: From Nuremberg to The Hague: United States Policy on Transitional Justice o Passed “Without Revisions”: highest possible evaluation awarded o Examiners: Professors William Schabas and Yuen Foong Khong o Supervisors: Professors Jennifer Welsh (primary) and Henry Shue (secondary) o Adaptation published (under revised title) by Oxford University Press • Master’s Thesis: Explaining the United States Policy to Prosecute Rwandan Génocidaires YALE LAW SCHOOL – J.D., 2009 • Editor-in-Chief, Yale Law & Policy Review • Managing Editor, Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal • Articles Editor, Yale Journal of International Law