Alfonso V, El Magnánimo and the Hungarian Throne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING of ARAGON

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING OF ARAGON By Robert Greene Written c. 1588-1591 Earliest Extant Edition: 1599 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2021. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. The COMICAL HISTORY of ALPHONSUS, KING OF ARAGON by ROBERT GREENE Written c. 1588-1591 Earliest Extant Edition: 1599 DRAMATIS PERSONAE: European Characters: Carinus, the rightful heir to the crown of Aragon. Alphonsus, his son. Flaminius, King of Aragon. INTRODUCTION to the PLAY. Albinius, a Lord of Aragon Laelius, a Lord of Aragon There is no point in denying that Alphonsus, King of Miles, a Lord of Aragon Aragon, Robert Greene's first effort as a dramatist, is Belinus, King of Naples. clearly inferior to Christopher Marlowe's Tamburlaine, the Fabius, a Lord of Naples. play (or plays, really) that inspired it. Having said that, a Duke of Millain (Milan). modern reader can still enjoy Greene's tale of his own un- conquerable hero, and will appreciate the fact that, unlike Eastern Characters: the works of other lesser playwrights, Alphonsus does move briskly along, with armies swooping breathlessly on Amurack, the Great Turk. and off the stage. Throw in Elizabethan drama's first talking Fausta, wife to Amurack. brass head, and a lot of revenge and murder, and the reader Iphigina, their daughter. will be amply rewarded. Arcastus, King of the Moors. The language of Alphonsus is also comparatively easy Claramont, King of Barbary. to follow, making it an excellent starter-play for those who Crocon, King of Arabia. -

The Latinist Poet-Viceroy of Peru and His Magnum Opus

Faventia 21/1 119-137 16/3/99 12:52 Página 119 Faventia 21/1, 1999119-137 The latinist poet-viceroy of Peru and his magnum opus Bengt Löfstedt W. Michael Mathes University of California-Los Angeles Data de recepció: 30/11/1997 Summary Diego de Benavides A descendent of one of the sons of King Alfonso VII of Castile and León, Juan Alonso de Benavides, who took his family name from the Leonese city granted to him by his father, Diego de Benavides de la Cueva y Bazán was born in 1582 in Santisteban del Puerto (Jaén). Son of the count of Santisteban del Puerto, a title granted by King Enrique IV to Díaz Sánchez in Jaén in 1473, he studied in the Colegio Mayor of San Bartolomé in the University of Salamanca, and followed both careers in letters and arms. He was the eighth count of Santisteban del Puerto, commander of Monreal in the Order of Santiago, count of Cocentina, title granted to Ximén Pérez de Corella by King Alfonso V of Aragón in 1448; count of El Risco, title granted to Pedro Dávila y Bracamonte by the Catholic Monarchs in 1475; and marquis of Las Navas, title granted to Pedro Dávila y Zúñiga, count of El Risco in 1533. As a result of his heroic actions in the Italian wars, on 11 August 1637 Benavides was granted the title of marquis of Solera by Philip IV, and he was subsequently appointed governor of Galicia and viceroy of Navarra. A royal coun- selor of war, he was a minister plenipotentiary at the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659, and arranged the marriage of Louis XIV with the Princess María Teresa of Austria as part of the terms of the teatry1. -

Constructing 'Race': the Catholic Church and the Evolution of Racial Categories and Gender in Colonial Mexico, 1521-1700

CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 i CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of the Catholic Church in defining racial categories and construction of the social order during and after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, then New Spain. The Catholic Church, at both the institutional and local levels, was vital to Spanish colonization and exercised power equal to the colonial state within the Americas. Therefore, its interests, specifically in connection to internal and external “threats,” effected New Spain society considerably. The growth of Protestantism, the Crown’s attempts to suppress Church influence in the colonies, and the power struggle between the secular and regular orders put the Spanish Catholic Church on the defensive. Its traditional roles and influence in Spanish society not only needed protecting, but reinforcing. As per tradition, the Church acted as cultural center once established in New Spain. However, the complex demographic challenged traditional parameters of social inclusion and exclusion which caused clergymen to revisit and refine conceptions of race and gender. -

Relations Between Portugal and Castile in the Late Middle Ages – 16Th Centuries

Palenzuela Relations between Portugal and Castile Relations between Portugal and Castile in the Late Middle Ages – 16th centuries Vicente Ángel Álvarez Palenzuela Relations between the Portuguese monarchy and the monarchies of Leon or Castile (the Kingdom of Castile was the historical continuation of the Kingdom of Leon) after the unification of the latter two kingdoms show a profundity, intensity and continuity not to be found among any of the other peninsular kingdoms during the Middle Ages, even though these were also very close. The bond between the two went far beyond merely diplomatic relations. The matrimonial unions between the two were so strong and frequent that it is possible to claim that both kingdoms were ruled by a single dynasty during the entire Middle Ages.1 Despite this, any attempt by one or the other to unify both kingdoms was destined to failure, and more often than not, to harsh confrontation leading to prolonged resentment and suspicions which were difficult to overcome.2 The very close relations are, in my opinion, the result of a common historical, cultural, and mental 1 This claim may seem to be exaggerated. However, I think it is fully endorsed by the frequent matrimonial alliances between the two ruling families. Five of the nine kings of the first Portuguese dynasty had Castilian wives: Alfonso II, Sancho II, Alfonso III, Alfonso IV, and Pedro I (and to some degree the same could be said of Fernando I). Leonor, wife of Duarte, was also Castilian, even if she was considered to be “Aragonese”, and so were the three successive wives of Manuel I. -

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity

The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Dandelet, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Ignacio E. Navarrete Summer 2015 The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance, and Morisco Identity © 2015 by Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry All Rights Reserved The Granada Venegas Family, 1431-1643: Nobility, Renaissance and Morisco Identity By Elizabeth Ashcroft Terry Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California-Berkeley Thomas Dandelet, Chair Abstract In the Spanish city of Granada, beginning with its conquest by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, Christian aesthetics, briefly Gothic, and then classical were imposed on the landscape. There, the revival of classical Roman culture took place against the backdrop of Islamic civilization. The Renaissance was brought to the city by its conquerors along with Christianity and Castilian law. When Granada fell, many Muslim leaders fled to North Africa. Other elite families stayed, collaborated with the new rulers and began to promote this new classical culture. The Granada Venegas were one of the families that stayed, and participated in the Renaissance in Granada by sponsoring a group of writers and poets, and they served the crown in various military capacities. They were royal, having descended from a Sultan who had ruled Granada in 1431. Cidi Yahya Al Nayar, the heir to this family, converted to Christianity prior to the conquest. Thus he was one of the Morisco elites most respected by the conquerors. -

COAT of ARMS of KING FERDINAND the CATHOLIC Kingdom of Naples(?), 1504-1512 Coat of Arms of King Ferdinand the Catholic Kingdom of Naples(?), 1504-1512

COAT OF ARMS OF KING FERDINAND THE CATHOLIC Kingdom of Naples(?), 1504-1512 Coat of Arms of King Ferdinand the Catholic Kingdom of Naples(?), 1504-1512 Marble 113 x 73.5 cm Carved out of marble, this coat of arms of King Ferdinand the Catholic represents both his lineage and his sovereignties. It is rectangular, with rounded inferior angles, ending in a point at the base and three points at the chief, a common shape in early sixteenth-century Spain. It is a quartered coat of arms, with its first and fourth quarters counterquartered with the arms of Castile-Leon, and its second and third quarters tierced per pale with the arms of Aragon, counterquartered per saltire with Sicily and counter-tierced with the arms of Hungary, Anjou and Jerusalem referring to Naples, besides the enté en point for Granada. It is crested by an open royal crown that has lost its rosette cresting, and it was originally supported by an eagle, as shown by the claws on the third and fourth quarters and the springing of the wings and the neck above the crown. Ferdinand the Catholic and the arms of Castile-Leon The counterquartered for Castile-Leon features, in the first and fourth quarters, a crenelated castle with three merlons, an emblem for the Castilian monarchs adopted by Alfonso VIII shortly before 1176 and, in the second and third quarters, the crowned lion rampant of the monarchs of Leon, of pre-heraldic origins, around the mid-eleventh century. The combination emerged as a symbol for the union of the kingdoms of Castile and Leon in 1230 effected by Ferdinand III the Saint. -

INTRODUCTION Thomas James Dandelet and John A. Marino

INTRODUCTION Thomas James Dandelet and John A. Marino On December 28–29, 1503, “the Great Captain,” Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, scored a definitive military victory for Ferdinand the Catholic against the French in the battle for the Kingdom of Naples at the Garigliano River. He had developed the strategic advantage of the Spanish tercios—light cavalry, infantry pikemen, and arquebus- armed infantry in a combined force—with his victory at Cerignola in the Tavoliere di Puglia eight months earlier on April 28. From there his Spanish forces marched to Naples, entered the city in tri- umph on May 16 to the jubilant reception of its noble citizenry, and departed again on June 18 for Gaeta and the final assault against the French at Garigliano. In Naples news of that victory touched off three days of continuous celebration, fireworks, and religious cer- emonies of thanksgiving with Gonzalo de Córdoba returning quietly on January 14, 1504, to become the first Spanish viceroy of the newly conquered Kingdom of Naples.1 With the Spanish conquest of southern Italy complete, together with the long-standing rule of Sicily from 1282 and Sardinia from 1297 through his Aragonese kingdom, Ferdinand the Catholic had taken a major step towards the eventual Spanish pacification and domination of much of Italy. Five aspects of the Spanish domination of Italy that changed the political landscape had been established before 1504. First, Italy had become an integral part of Aragonese ambitions for Catalan mercantile expansion and a Western Mediterranean “empire.” Sicily, Sardinia, and Naples were essential pieces of Aragon’s European puzzle, and partnering with Genoese financiers was common prac- tice for all three of the Iberian powers—Aragon, Castile, and Por- tugal—in their designs on North and West Africa, and beyond. -

Goya: a Portrait of the Artist

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. c ontents Color plates follow page 180 Main and Supporting Characters ix Acknowledgments xvii Introduction xxi PArt i. An Artist from ZArAGoZA 1 Early Years 3 2 First Trials 9 3 Italy 16 4 Triumphs of a Native Son 24 5 Settings for the Court of Carlos III 32 6 “Of my invention” 37 7 Goya Meets Velázquez 44 8 The Zaragoza Affair 54 PArt II. the PAth of A coUrt PAinter 9 Floridablanca 63 10 Don Luis 72 11 “The happiest man” 81 12 “God has distinguished us” 90 13 A Coronation under Darkening Skies 97 14 Changing Times 107 15 The Best of Times, the Worst of Times 117 For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. PArt III. Witness of A siLent WorLd 16 “There are no rules in painting” 129 17 Goya and the Duchess 141 18 Dreaming, Enlightened 152 19 Subir y bajar 161 20 “The king and queen are crazy about your friend” 170 21 The French Connection 180 22 Absences 188 23 Society High and Low 198 24 A Monarchy at Twilight 205 PArt IV. WAr And restorAtion 25 The Old Order Falls 213 26 In the Shadow of a New Regime 223 27 On the Home Front 236 28 The Spoils of War 244 29 Portraits of a New Order 254 PArt v. -

Intereses Políticos Y Religiosos En La Canonización De Vicente Ferrer

ANUARIO DE ESTUDIOS MEDIEVALES 49/1, enero-junio de 2019, pp. 261-286 ISSN 0066-5061 https://doi.org/10.3989/aem.2019.49.1.10 POWER AND THE HOLY: POLITICAL AND RELIGIOUS INTERESTS IN THE CANONIZATION OF VINCENT FERRER EL PODER Y LO SAGRADO: INTERESES POLÍTICOS Y RELIGIOSOS EN LA CANONIZACIÓN DE VICENTE FERRER LAURA ACKERMAN SMOLLER University of Rochester, USA http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4728-6002 Abstract: This article explores some of the political and religious considerations in the canonization of St. Vincent Ferrer through a close and sometimes against the grain reading of canonization ma- terials, letters, and early hagiography. The most aggressive promoters of Vincent’s canonization were the Montfort dukes of Brittany, where the saint is buried, and who used their association with the holy friar to assert sacred legitimacy for their dynasty, which had come to power as the result of a bloody civil war and which adopted a quasi-royal image along the lines of the French monarchy. In Vincent’s native Aragon, the situation was more complicated. The friar had helped bring the Trastámara dynasty to power there in 1412, but Vincent’s role in announcing the crown of Aragon’s 1416 withdrawal of obedience from the Aragonese pope Benedict XIII would diminish his symbolic value in his homeland. Only after Alfonso V’s conquest of the kingdom of Naples did the Trastámaras begin to push in earnest for the opening of a canonization process as part of a strategy to show divine favor for the new Aragonese regime in Naples. -

A Critical Study of Lope Do Vega's, Don Lope Do Cardona

A critical study of Lope de Vega's Don Lope de Cardona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bork, Albert William Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:15:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553382 A Critical study of Lope do Vega’s, Don Lope do Cardona - ' ' t>y Albert william Bork A th esis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Spanish in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1938 Approved: 7 Major professor rDat5 l - i & r r ■ ' JLlBRkVX <£979/ /93$>. S’ e - ^ . Z - TABLE OF GGMmiTS page Preface.............................................. ..1-111 Introduction Principal editions and criticisms.....................1 Historical Background 1# Cast, general historical backgroundand argument of tLe play...............................4 2. Alfonso IV, in history and In this drama..........1 3 3. Pedro IV, In history and in this drama............2 0 4; Tres Pedros oomos Reyes en un tiempo. as a - dramatic idea............ .......; ................... ...2 3 5. Don Lop® de Cardona:hia identity.................4 8 a. The ballad on Don Lope as a possible source..54 -b. The various crSnlcas as source®..............5 7 Don Lope de Cardona: A Defense of the Duke deSessa.......7 6 Versification and Date of Composition..•..............,.,,9 5 Influence on Other Literatures ; ^ 1. -

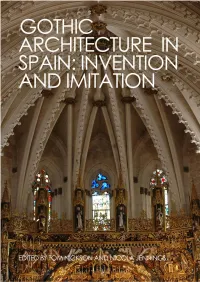

Gothic Architecture in Spain: Invention and Imitation

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN SPAIN: INVENTION AND IMITATION Edited by: Tom Nickson Nicola Jennings COURTAULD Acknowledgements BOOKS Publication of this e-book was generously Gothic Architecture in Spain: Invention and Imitation ONLINE supported by Sackler Research Forum of The Edited by Tom Nickson and Nicola Jennings Courtauld Institute of Art and by the Office of Scientific and Cultural Affairs of the Spanish With contributions by: Embassy in London. Further funds came from the Colnaghi Foundation, which also sponsored the Tom Nickson conference from which these papers derive. The Henrik Karge editors are especially grateful to Dr Steven Brindle Javier Martínez de Aguirre and to the second anonymous reader (from Spain) Encarna Montero for their careful reviews of all the essays in this Amadeo Serra Desfilis collection. We also thank Andrew Cummings, Nicola Jennings who carefully copyedited all the texts, as well as Diana Olivares Alixe Bovey, Maria Mileeva and Grace Williams, Costanza Beltrami who supported this e-book at different stages of its Nicolás Menéndez González production. Begoña Alonso Ruiz ISBN 978-1-907485-12-1 Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Managing Editor: Maria Mileeva Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Vernon Square, Penton Rise, King’s Cross, London, WC1X 9EW © 2020, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. -

Legal Status of Jewish Converts to Christianity in Southern Italy and Provence

Legal Status of Jewish Converts to Christianity in Southern Italy and Provence Nadia Zeldes A comprehensive approach to the history of the Mediterranean European Jewish communities that emphasizes common factors is relatively recent. 1 Among the first to draw attention to these common factors was Maurice Kriegel in his Les Juifs à la fin du Moyen Age dans l’Europe méditerranéenne .2 Kriegel’s study focuses on social, cultural, and economic aspects of Jewish-Christian interrelations, tracing the decline in the status of the Jews in the Iberian lands and Southern France from the thirteenth century to the age of the expulsions (1492- 1501). According to Kriegel, the increasing segregation of the Jews contributed to the deterioration of their image and the weakening of their position in Christian society, which in turn led to expulsion and conversion. The thirteenth century saw a general decline in the status of the Jews in Christian Europe. The reasons for the deterioration of the status of the Jews in this period are manifold, and probably cannot be attributed to a specific factor or event. Most scholars now agree that changes such as increased urbanization, the attempts to create a cohesive Christian community, the rise of the universities, and new intellectual trends, as well as the founding of the Mendicant orders and their increasing influence in the later Middle Ages, played an important role in the worsening image of the Jew and the marginalization of the Jews. Urbanization meant that Jewish merchants and craftsmen became economic rivals instead of much needed suppliers of unique services, as was the case in the early Middle Ages.