ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Preliminary Pages [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9128/preliminary-pages-pdf-199128.webp)

Preliminary Pages [PDF]

THE SUBSTANCE OF STYLE HOW SINGING CREATES SOUND IN LIEDER RECORDINGS, 1902-1939 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rebecca Mara Plack May 2008 © 2008 Rebecca Mara Plack THE SUBSTANCE OF STYLE HOW SINGING CREATES SOUND IN LIEDER RECORDINGS, 1902-1939 Rebecca Mara Plack, Ph. D. Cornell University 2008 In this dissertation, I examine the relationship between vocal technique and performance style through 165 audio clips of early Lieder recordings. I proceed from the starting point that many stylistic gestures are in fact grounded in a singer’s habitual vocalism. Vibrato, tempo and rubato are directly affected by a singer’s voice type and his physical condition, and portamento has long been a technical term as well as a stylistic one. If we consider these technical underpinnings of style, we are inevitably moved to ask: how do a singer’s vocal habits affect what we perceive to be his style? Does a singer’s habitual vocalism result in his being more likely to make certain style gestures, or even unable to make others? To address these questions, I begin by defining a vocabulary that draws on three sources: the language of vocal pedagogy, data derived from voice science, and evidence drawn from recordings themselves. In the process, I also consider how some Lieder singers distorted the word “technique,” using it to signify emotional detachment. Next, I examine the ways in which a recording represents the performer, addressing how singers are affected by both changing aesthetics and the aging process; both of these lead to a discussion of how consistently some performers make certain stylistic gestures throughout their recordings. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

Universität Mozarteum Salzburg – Wo Aus Begabung Exzellenz Wird

CONTENTS Mission Statement 5 The Mozarteum University 6 History 11 Conducting, Composition and Music Theory 14 Study Courses for Instruments, Keyboard Instruments 16 String and Plucked String Instruments, Wind Instruments and Percussion 18 Voice and Music-Theatre 20 Acting and Stage Directing 22 Stage and Costume Design, Film and Exhibition Architecture 23 Musicology 24 Music Educational Theory, INHALT Orff Institute for Elementary Music and Dance Pedagogy 26 2 · 05 Mission Statement 5 Visual Arts, Educational Theory of Art Die Universität Mozarteum Salzburg 6 and Craftwork 28 Die Geschichte 8 Studying at the Mozarteum University 31 Dirigieren, Komposition und Musiktheorie 14 Symphony Orchestra, Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg 32 Instrumentalstudium, Tasteninstrumente 16 Mozarteum International Summer Academy, Streich- und Zupfinstrumente, International Mozart Competition 34 Blas- und Schlaginstrumente 18 Leopold Mozart Institute for Encouraging Gesang und Musiktheater 20 Talent, History of the Reception of Music, Schauspiel und Regie, New Music, Early Music, Mozart Bühnen- und Kostümgestaltung, Interpretation, Game Research, Innsbruck Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur 22 Baroque, Sándor Végh Institute Musikwissenschaft 24 of Chamber Music 38 Musikpädagogik, Orff-Institut für Research Funding, Science and Art 40 Elementare Musik- und Tanzpädagogik 26 Institute of Equality and Gender Studies 41 Bildende Künste, Distinguished Persons and Kunst- und Werkpädagogik 28 Association of Friends 42 Studieren an der Universität Mozarteum 30 -

A Collection of Stan Ruttenberg's Reviews of Mahler Recordings From

A collection of Stan Ruttenberg’s Reviews of Mahler Recordings from the Archives Of the Colorado MahlerFest (Symphonies 3 through 7 and Kindertotenlieder) Colorado MahlerFest XIII Recordings of the Mahler Third Symphony Of the fifty recordings listed in Peter Fülöp’s monumental discography (up to 1955, and many more have been added since then), I review here fifteen at my disposal, leaving out two by Boulez and one by Scherchen as not as worthy as the others. All of these fifteen are recommendable, all with fine points, all with some or more weaknesses. I cannot rank them in any numerical order, but I can say that there are four which I would rather hear more than the others — my desert island choices. I am glad to have the others for their own particular merits. Getting ready for MFest XIII we discovered that the matter of score versions and parts is complex. I use the Dover score, no date but attributed to Universal Edition; my guess this is an early version. The Kalmus edition is copied from who knows which published version. Then there is the “Critical Edition,” prepared by the Mahler Gesellschaft, Vienna. I can find two major discrepancies between the Dover/Universal and the Critical (I) the lack of horns at RN25-5, doubling the string riff and (ii) only two harp glissandi at the middle of RN28, whereas the Critical has three. Our first horn found another. Both the Dover and Critical have the horn doublings, written ff at RN 67, but only a few conductors observe them. -

Richard Wagner in München

Richard Wagner in München Allitera Verlag MÜNCHNER VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN ZUR MUSIKGESCHICHTE Begründet von Thrasybulos G. Georgiades Fortgeführt von Theodor Göllner Herausgegeben von Hartmut Schick Band 76 Richard Wagner in München. Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 RICHARD WAGNER IN MÜNCHEN Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 Herausgegeben von Sebastian Bolz und Hartmut Schick Weitere Informationen über den Verlag und sein Programm unter: www.allitera.de Dezember 2015 Allitera Verlag Ein Verlag der Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 der Einzelbeiträge bei den AutorInnen Satz und Layout: Sebastian Bolz und Friedrich Wall Printed in Germany · ISBN 978-3-86906-790-2 Inhalt Vorwort ..................................................... 7 Abkürzungen ................................................ 9 Hartmut Schick Zwischen Skandal und Triumph: Richard Wagners Wirken in München ... 11 Ulrich Konrad Münchner G’schichten. Von Isolde, Parsifal und dem Messelesen ......... 37 Katharina Weigand König Ludwig II. – politische und biografische Wirklichkeiten jenseits von Wagner, Kunst und Oper .................................... 47 Jürgen Schläder Wagners Theater und Ludwigs Politik. Die Meistersinger als Instrument kultureller Identifikation ............... 63 Markus Kiesel »Was geht mich alle Baukunst der Welt an!« Wagners Münchener Festspielhausprojekte ......................... -

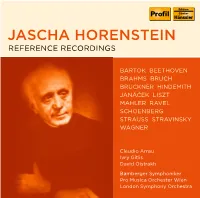

Jascha Horenstein Reference Recordings

JASCHA HORENSTEIN REFERENCE RECORDINGS BARTOK BEETHOVEN BRAHMS BRUCH BRUCKNER HINDEMITH JANÁČEK LISZT MAHLER RAVEL SCHOENBERG STRAUSS STRAVINSKY WAGNER Claudio Arrau Ivry Gitlis David Oistrakh Bamberger Symphoniker Pro Musica Orchester Wien London Symphony Orchestra JASCHA HORENSTEIN REFERENCE RECORDINGS CD 1 CD 2 CD 3 CD 4 Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) Paul Hindemith (1895 – 1963) SYMPHONY No. 3 IN D MINOR SYMPHONY No. 3 IN D MINOR SYMPHONY No. 8 IN C MINOR SYMPHONY „MATHIS DER MALER“ Sinfonie Nr. 3, d-Moll Sinfonie Nr. 3, d-Moll Sinfonie Nr. 8, c-Moll 1. I. Concert of Angels / Engelkonzert 9'25 1. I. Kräftig. Entschieden 30'29 1. VI. Adagio 21'14 (1890 Version) Ruhig bewegt. Ziemlich lebhafte Halbe 2. II. Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig 8'40 1. I. Allegro moderato 13'40 2. II. Entombment / Grablegung 4'57 SYMPHONY No. 1 IN D MAJOR („Titan“) 3. III. Comodo. Scherzando 16'09 2. II. Scherzo: Allegro moderato 14'59 Sehr langsam Sinfonie Nr. 1, D-Dur 4. IV. Sehr langsam. Misterioso 8'52 3. III. Adagio: Feierlich langsam, 3. III. The Temptation of St. Antony / 5. V. Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck 4'07 2. I. Langsam. Schleppend 16'47 doch nicht schleppend 25'26 Versuchung des Hl. Antonius 15'09 (cont. on disc 2) 3. II. Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell 8'13 4. IV. Finale: Feierlich, nicht schnell 22'35 Sehr langsam. Frei im Zeitmaß. Sehr lebhaft 4. III. Feierlich und gemessen, Helen Watts, contralto/Alt (4) ohne zu schleppen 11'35 Pro Musica Orchester, Wien Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) Highgate School Choir, Orpington Junior Singers (5) 5. -

ARSC Journal

RICHARD STRAUSS' S RECORDINGS: A COMPLETE DISCOGRAPHY by Peter Morse If Richard Strauss had never composed a bar of music, he would be known today as one of the great conductors of the century. We forget, in the shadow of his musical masterpieces, that he was at various times conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic and general music director of both the Berlin Opera and the Vienna Opera. He conducted the world premiers of such works as Humperdinck's "Hansel and Gretel" and Mahler's first and second symphonies. His conducting of Mozart was particularly praised. He cut away a great deal of romantic excess which had accum ulated during the nineteenth century and restored to Mozart's music the coolness and clarity of the original. In this he was, with Toscanini, one of the modern founders of the new orchestral style. (Strauss allowed more liberties to be taken with vocal works.) Because he was so highly qualified as a conductor, his interpre tations of his own music deserve even more attention than those of most composers. The same cool style may be heard in his treatment of his own works, ranging from "Don Juan" to the "Intermezzo" excerpts. Strauss the composer wrote in his scores all the directions that were needed by Strauss the conductor. He had little tolerance for further elaboration on his orchestral music. Today, every conductor who wishes to perform Strauss's music should study the composer's re cordings as well as the score. Even if one disagrees with Strauss's interpretations, it is inexcusable to ignore them. -

Building a Library

BUILDING A LIBRARY All selections were made from recordings available in the UK at the time of the broadcast and are full price unless otherwise stated. CD Review cannot guarantee that they have not subsequently been deleted. KEY: CD = compact disc c/w = coupled with SIS = a recording which is only available through EMI’s Special Import Service IMS = a recording which is only available through Universal Classics' Import Music Service CONTENTS September 1999 – July 2000 .................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 September 2000 – July 2001 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 24 September 2001 – July 2002 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 46 September 2002 – July 2003 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 74 September 2003 – July 2004 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 98 September 2004 – July 2005 ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Hans Pfitzner 1 Hans Pfitzner

Hans Pfitzner 1 Hans Pfitzner Hans Erich Pfitzner (* 5. Mai 1869 in Moskau; † 22. Mai 1949 in Salzburg) war ein deutscher Komponist und Dirigent. Leben Pfitzner war der Sohn eines Orchester-Violinisten und erhielt schon früh von seinem Vater Musikunterricht. Die Familie zog 1872 nach Frankfurt am Main um. Bereits mit elf Jahren komponierte der kleine Hans seine ersten Werke, 1884 entstanden die ersten überlieferten Lieder. Von 1886 bis 1890 studierte Pfitzner am Hoch’schen Konservatorium in Frankfurt Komposition bei Iwan Knorr und Klavier bei James Kwast. Er unterrichtete von 1892 bis 1893 am Koblenzer Konservatorium und wurde 1894 Kapellmeister-Volontär am Stadttheater in Mainz. 1895 kamen dort die ersten größeren Werke Pfitzners zur Hans Pfitzner, 1905 Uraufführung, die Oper Der arme Heinrich und die Schauspielmusik zu Das Fest auf Solhaug von Henrik Ibsen. 1897 übersiedelte er nach Berlin und wurde Lehrer am Stern’schen Konservatorium. Er heiratete 1898 Mimi Kwast, die Tochter seines ehemaligen Klavierlehrers. 1903 wurde Pfitzner erster Kapellmeister am Berliner Theater des Westens, sein erster Sohn Paul wurde geboren. An der Wiener Hofoper unter Gustav Mahler wurde 1905 Pfitzners zweite Oper Die Rose vom Liebesgarten aufgeführt. Sein zweiter Sohn Peter wurde 1906 geboren, seine Tochter Agnes 1908. Im gleichen Jahr zog die Familie nach Straßburg. Pfitzner leitete dort das Städtische Konservatorium und die Sinfoniekonzerte der Straßburger Philharmoniker. 1910 übernahm er zugleich die musikalische Leitung der Straßburger Oper, wo er auch als Regisseur wirkte. 1913 erfolgte seine Ernennung zum Professor. 1917 wurde im Münchner Prinzregententheater unter Bruno Walter die „Musikalische Legende“ Palestrina uraufgeführt, die als Pfitzners bedeutendstes Werk gilt. -

Rádió Világhíradó

íládiá VUà^Uwadâ s z w tÿ d s z t a Volaf» 66. M atou KÁLMÁN IMRE RÁDIÓVERSEI: er , ^ J a c / i n ^ Jsenes zsui Lili, szeretlek! szólt az ifjú, A rádió mellett eltűnődtem, A járda, melyen állsz is, szent! Csinálni kék egy zenés zsúrt itt . A nő ékszerbolt előtt állott Vettem hát egy fél műsort Brünnből S a vallomás fadinyba ment. É t hozzája egy fél frankfurtit. * * (ssenc/zende/el ^t)ízá ffá s- ie/eníés A csend körül folynak most viták Végre kaphatnánk egyszer m á s t is S hogy fogalmunk legyen a bajról. A déli műsorok helyében. Adjon helyszíni közvetítést Tekintve, hogy a vízállás m á r A rádió a pesti zajról. B ent van az emberek fejében. Rádióban p a d io n O V O fogalom Václ-a. 27-29. |Pi>rijl«-p4l«ía %jfi 1bMBIMBK.<a»^«Mca9æm!i!Eni iS -i-tk A külföldi műsorrészben a délelőtti órákat dűlt számokkal, a délutáni órákat kövér számokkal jelezzük augusztus 6 VASARNAP augusztus ( tile). Wagncr:^ria az tlstenek alko BUDAPEST I. nya» c. operából (Iv a r Andrcsen). Csajkovszkij: Melodie (Hnberman 8.23: Hírek. Bronislav). Mascagni: írisz — szere nád (Aureliane Pertile). Friedman: 8.1': Hírek a Jámbor eoról, a hely Tabatière à musique (ignaz Fried színről. man). Csajkovszkij: A templomban #.86: Egyházi zene és szentbeszéd a (Don Ko/ák-Kórns). R ubinstein— gödöllői IV. «Világjamboree»-ról. Az Popper: Melódia (W. IT. Sünire). Ca- ünnepi szentmisét a Hercegprímás purro—Di Capua: A ria (AurellaoO Pertile). tír őeminenciája mondja. A szentbe szédet dr. Tóth Tihamér mondja. -

Auktionskatalog 17

AUTOGRAPHEN-AUKTION 31. März 2007 Los 805 Johann Strauß (Sohn) Axel Schmolt Autographen-Auktionen 47807 Krefeld Steinrath 10 Telefon 02151-93 10 90 Telefax 02151-93 10 9 99 E-Mail: [email protected] AUTOGRAPHEN-AUKTION Inhaltsverzeichnis Los-Nr. Geschichte - Römisch-deutsche Kaiser 1 - 3 - Bayern - Haus Wittelsbach 4 - 10 - Preußen 11 - 34 - I. Weltkrieg 35 - 48 - Weimarer Republik 49 - 59 - Deutschland 1933-1945 60 - 184 - Deutsche Geschichte seit 1945 185 - 226 - Geschichte des Auslands bis 1945 227 - 258 - Geschichte des Auslands seit 1945 259 - 368 - Kirche-Religion 369 - 384 Literatur 385 - 522 Musik 523 - 846 - Oper-Operette (Sänger/- innen) 847 - 989 Bühne - Film - Tanz 990 - 1214 Bildende Kunst 1215 - 1335 Wissenschaft 1336 - 1394 - Forschungsreisende und Geographen 1395 - 1406 Luftfahrt 1407 - 1414 Weltraumfahrt 1415 - 1425 Sport 1426 - 1532 Widmungsexemplare - Signierte Bücher 1533 - 1583 Sammlungen - Konvolute 1584 - 1603 Autographen – Auktion am Samstag, den 31. März 2007 47807 Krefeld, Steinrath 10 Die Versteigerung beginnt um 11.00 Uhr. Pausen nach den Gebieten Literatur und Bühne-Film-Tanz Im Auktionssaal sind wir zu erreichen: Telefon (02151) 93 10 90 und Fax (02151) 93 10 999 Während der Auktion findet im Auktionssaal keine Besichtigung statt. Die Besichtigung in unseren Geschäftsräumen kann zu den nachfolgenden Terminen wahrgenommen werden oder nach vorheriger Vereinbarung. 24.03.2007 (Samstag) von 11.00 bis 16.00 Uhr 26.03.2007 – 30.03.2007 von 11.00 bis 17.00 Uhr Bei Überweisung der Katalogschutzgebühr von EUR 10,- senden wir Ihnen gerne die Ergebnisliste der Auktion zu. Autographen - Auktionen Axel Schmolt Steinrath 10, 47807 Krefeld Tel. 02151 – 93 10 90 / Fax 02151 – 93 10 999 Internet: http://www.schmolt.de Wichtiger Hinweis: Mit der Abgabe der Gebote für die Autographen, Dokumente und Bildpostkarten aus der NS-Zeit verpflich- tet sich der Bieter dazu, diese Ware lediglich für historisch-wissenschaftliche Sammelzwecke zu erwerben und in keiner Weise propagandistisch im Sinne des § 86 StGB zu benutzen. -

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books Are All in Good, Used Condition (No Damage Unless Described)

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). “As new” should be just that. “Excellent” would be similar to 2, light dust jacket or cover marks but no problems. “Good” would be similar to 3 (use wear). Any damage or marking is mentioned. DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket “THE RECORD COLLECTOR” MAGAZINE Given below is the featured artist(s) of each issue (D=discography, B-biographical sketch). All copies are in fine condition (with the possibility of an index mark or possible check marks, occasional underlinings, but no physical damage such as tears, loose seams, etc., unless otherwise indicated. MINIMUM BID $5.00 PER MAGAZINE 8002. II/1-6. (Jan.-June, 1947). Re-issue of first half of Volume II, originally in mimeographed format. 8006. III/3. Götterdämmerung on Records; The Victor News Letter; American Record Notes, etc. 8007. III/4. Rethberg Discography; more Götterdämmerung; Cloe Elmo; Russian Operatic Discs, etc. 8010. III/7. Dating Victor Records; A Brief Glance Back; More “Historical Record” Amendments, etc. 8011. III/8. Iris addenda; Russian Operatic Records; More on Affre; The Aldeburgh Festival, etc. 8012. III/9. Edison Disc Records; Celebrities at Birmingham; Puccini Operas; More on Götterdämmerung, etc. 8013. III/10. A Santley Curiosity; Matrix & Serial Numbers; My Most Inartistic Recording; etc. 8015. III/12. Bauer Amendments; Italian Vocal Issues Jan.-Aug. 1948; Philadelphia Record Society, etc. 8017. IV/2. Giovanni Zenatello (D); “Otello” discography, etc. 8018. IV/3. Medea Mei-Figner (D); Another Curiosity; Italian Vocal Issues, etc. 8019. IV/4 The DeReszke Mystery; Eugenia Mantelli (D and commentary), To Help the Junior Collector, etc.