Ce1999116.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

July 26, 2020

JULY 26, 2020 HOME OF THE $3 MILLION ALL AMERICAN FUTURITY RaceRuidoso.com 2002 Sudderth Dr., Ruidoso NM 88345 RHONDA ROMACK-BURNS 575-937-3000 [email protected] OFFICE 575-257-3000 31ST DAY OF RACING • SUNDAY, JULY 26, 2020 • POST TIME 1:00PM Weekend Preview It’s time for the Zia Festival at Ruidoso Downs Race Track, and the race card features a great line-up of trials and stakes races all weekend that celebrate New Mexico-bred Quarter Horses and Thoroughbreds. F RI DAY SUNDAY RIO GRANDE SENORITA FUTURITY TRIALS ZIA FUTURITY (GI) 5 ½ Furlongs | 2-year-old fillies Purse = $392,547 | 400 Yards | 2-year-olds RIO GRANDE SENOR FUTURITY TRIALS ZIA QH JUVENILE 5 ½ Furlongs | 2-year-old colts & geldings Purse = $50,000 | 400 Yards | 2-year-olds SATURDAY ZIA 870 CHAMPIONSHIP SIERRA STARLET Purse = $50,000 | 870 Yards | 3-year-old & up Purse = $50,000 | 5 ½ Furlongs | 3-year-old & up fillies ROAD RUNNER HANDICAP ZIA HANDICAP (RG2) Purse = $50,000 | 5 ½ Furlongs | 3-year-old fillies Purse = $50,000 | 400 Yards | 3-year-old & up LINCOLN HANDICAP ZIA QH DERBY (GII) Purse = $50,000 | 6 Furlongs | 3-year-old fillies & mares Purse = $183,073 | 400 Yards | 3-year-olds LAND OF ENCHANTMENT STAKES Purse = $50,000 | 7 ½ Furlongs | 3-year-old & up SIERRA BLANCA HANDICAP Purse = $50,000 | 5 ½ Furlongs | 3-year-old & up Remember while you are here with us, we kindly ask that everyone do their part to adhere to the COVID-Safe Practices (CSPs) that have been put into place as part of our plan that allows us to have fans here in attendance. -

Monthly Performance Reports

* All Financial Data is Preliminary and Unaudited * MonthlyMonthly PerformancePerformance ReportReport forfor SeptemberSeptember 20112011 November 2, 2011 Table of Contents Page # A. Financial Results 1. Summary Performance Report versus Budget Operating Results - Month A-1.1 Operating Results - Year to Date A-1.2 Capital Spend Summary - Month A-1.3 Capital Spend Summary - Year to Date A-1.4 ARRA Capital Program Summary A-1.5 2. Metrics Metrics A-2.1 Inventory Turns / Balance A-2.9 3. Ridership and Revenue Ticket Revenue and Ridership Summary A-3.1 Ridership and Ticket Revenue by Route Current Month A-3.4 Year to Date A-3.5 Ridership and Revenue - Sleeper Class A-3.6 4. Actual and Forecast Results Income Statement by Business Lines Month, YTD vs. Budget and Prior Year A-4.1 Capital Project Overview Regular Projects A-4.8 ARRA Projects A-4.10 Mechanical Production Report A-4.13 Engineering Production Report A-4.15 5. Actual Analysis to Prior Year Consolidated Income Statement A-5.1 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows A-5.4 Balance Sheet A-5.5 B. Legislative Report Legislative Updates B-1 C. Route Performance Report – Fully Allocated Summary YTD Route Results C-1 D. Workforce Statistics Headcount Data D-1 Other Employee Costs D-3 E. Performance Indicators Delay Minutes Summary Report E-1 Host Railroad Delay Minutes Report E-2 On-Time Performance E-7 i IINNAANNCCIIAALL EESSUULLTTSS Operating Results for the Month of September 2011 ($ millions) September September Fav/(Unfav) FY11 Budget to Budget Comments Revenues: Adjusted Ticket Revenue $150.7 $147.0 $3.7 Acela and Corridor routes partially offset by effects of weather and host railroad track work. -

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................2 2 A HISTORY..............................................................................................3 3 ROLLING STOCK......................................................................................4 3.1 EMD AEM-7 Electric Locomotive .......................................................................................4 3.2 Amtrak Amfleet Coaches .................................................................................................5 4 SCENARIOS.............................................................................................6 4.1 Go Newark....................................................................................................................6 4.2 New Jersey Trenton .......................................................................................................6 4.3 Spirit or Transportation ..................................................................................................6 4.4 The Big Apple................................................................................................................6 4.5 Early Clocker.................................................................................................................7 4.6 Evening Clocker.............................................................................................................7 4.7 Northeast Regional ........................................................................................................7 -

Transportation Planning for the Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad Corridor

VOLUME I Executive Summary and Main Report Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad Corridor Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation March 2004 Disclaimer: This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation solely in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof, nor does it express any opinion whatsoever on the merit or desirability of the project(s) described herein. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Any trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. Note: In an effort to better inform the public, this document contains references to a number of Internet web sites. Web site locations change rapidly and, while every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of these references, they may prove to be invalid in the future. Should an FRA document prove difficult to find, readers should access the FRA web site (www.fra.dot.gov) and search by the document’s title or subject. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FRA/RDV-04/05.I 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the March 2004 Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad 6. Performing Organization Code Corridor⎯Volume I: Executive Summary and Main Report 7. Authors: 8. Performing Organization Report No. For the engineering contractor: Michael C. Holowaty, Project Manager For the sponsoring agency: Richard U. Cogswell and Neil E. Moyer 9. -

Evaluation of Options for Improving Amtrak's

U.S. Department EVALUATION OF OPTIONS FOR of Transportation Federal Railroad IMPROVING AMTRAK’S PASSENGER Administration ACCOUNTABILITY SYSTEM Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-05/06 Final Report This document is available to the public through the National December 2005 Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161. This document is also available on the FRA Web site at www.fra.dot.gov. Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Notice The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2005 Final Report December 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Evaluation of Options for Improving Amtrak’s Passenger Accountability System RR93/CB043 6. -

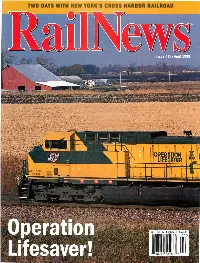

TWO DAYS with NEW YORK's CROSS HARBOR RAILROAD Belt Lines: EJ&E

TWO DAYS WITH NEW YORK'S CROSS HARBOR RAILROAD Belt Lines: EJ&E .. IHB .. B&OCT • Mainline action on the Elgin Joliet & Eastern, Indiana Harbor Belt, and the former Baltimore & Ohio Chica go Terminal (now CSX). • See over 70 trains from: EJ&E, IHB, CSX, Up, C&NW, CP Rail, Conrail, Wisconsin Central, BN, ATSF, CN, look at the mainline action on some of the GTW, Sp, Norfolk Southern, Chicago Chicago area and northwest Indiana belt lines. Short Line, Amtrak, and more. This program focuses on some of the mainline action on the Elgin Joliet & Eastern (EJ&E), Indiana Har • Locations include Rondout cross Abor Belt (IHB) and CSX's former Baltimore & Ohio Chi ing, Leithton, Hawthorne Hills, ca-go Terminal (B&OCT). The EJ&E is the outermost Belt West Chicago crossing, Eola cross line around the Chicago area and crosses every major railroad coming into Chicago! The IHB and former ing, Aurora, Walker Junction, B&OCT intersect with most of the major railroads closer Plainfield, Des Plaines River to and in Chicago. The EJ&E and IHB are heavy steel crossing, Joliet, Griffith crossing, haulers as well as providers of transfer service among Van Loon crossing, Gary, Whiting, the other railroads. Many of the major roads run road Hammond crossing, State Line trains and transfers on these belt lines and we capture the action. In addition we capture several crossing (lUIN), Blue Island Junction, EJ&E and IHB trains with their well-maintained classic EMD power and cabooses! There are seven ac tive tower junctions shown in this program! Video captured from 1995 through late 1997. -

Northeast Corridor Through-Ticketing Study

Northeast Corridor Through-Ticketing Study November 2018 Prepared by the Northeast Corridor Commission with support from: Foursquare ITP High Street Consulting Mathew Coogan RSG WSP Northeast Corridor Commission 1 CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Models for Through-Ticketing .................................................................................................................................... 2 Market Demand for Through-Ticketing .................................................................................................................... 2 Technical Challenges Associated with Through-Ticketing ..................................................................................... 3 Results and Recommendations .................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 What is Through-Ticketing? ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Study Background............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Study Methodology and Organization ......................................................................................................... -

Analysis of Cost Savings on Amtrak's Long-Distance

ANALYSIS OF COST SAVINGS ON AMTRAK’S LONG-DISTANCE SERVICES Report Number: CR-2005-068 Date Issued: July 22, 2005 Memorandum U.S. Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary of Transportation Office of Inspector General Subject: ACTION: Report on Date: July 22, 2005 Analysis of Cost Savings on Amtrak’s Long-Distance Services Report No. CR-2005-068 From: Kenneth M. Mead Reply to Attn. of: JA-50 Inspector General To: The Secretary Deputy Secretary General Counsel National Railroad Passenger Corporation Board of Directors Long-distance intercity passenger rail service in the United States has sparked widespread controversy, in large part because of its heavy subsidies. In fact, Congress directed Amtrak to be operationally self-sufficient by 2002 and currently there is no authorization for the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak). Meanwhile the subsidy has grown. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2004, long- distance trains (those with routes over 500 miles) cumulatively incurred operating losses of more than $600 million.1 There is no sign that this trend of large losses from long-distance service can be reversed by engaging in business as usual. Although one approach to reducing the losses posted by Amtrak is to simply eliminate long-distance service, this report considers a less drastic measure, namely to selectively reduce costs while continuing to provide basic long-distance service to meet the mobility needs of rural communities that may not have access to other transportation alternatives. Many of those who advocate retaining Amtrak’s long-distance routes argue that Amtrak service along those routes is needed to meet basic transportation needs of communities that are far from major metropolitan areas. -

SMART Transportation Division News

SHEET METAL | A I R | R A I L | T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Transportation Division News International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers Volume 49 • Number 7/8 • July/August 2017 National negotiations update: Unions say contract negotiations take a step backward As part of our ongoing effort to conclude dations that could come from a Presidential https://static.smart-union.org/worksite/Contract - national contract negotiations, the Coordinat - Emergency Board appointed by President Neg/NCCC_2017-06-29_Synopsis_and_Pro - ed Bargaining Group (CBG) met with the Trump, and ultimately be imposed on the posal.pdf or by visiting www.smart-union.org/td. nation’s freight rail Carriers (NCCC) for three employees by a Congress that already has More information will be forthcoming after the days during the week of June 26. These enacted or is pushing for changes in longstand - next mediation sessions in July and August. efforts were part of our ongoing mediation ing labor laws that protect employee rights. We appreciate your continuing support. process, mandated by the Railway Labor Act We of course are frustrated by the Carriers’ when the parties have been unable to reach hard-line attitude. But we will not let this FEMA appoints SMART TD’s a voluntary agreement, and managed by the stand in our way. In spite of this latest turn of National Mediation Board. events, the CBG will not give up its efforts to Hayes as rail labor rep. Despite the CBG’s best efforts to achieve a voluntary settlement reach a fair agreement with the that is fair and protects our NCCC, the mediation process members’ best interests. -

Monthly Performance Report for September 2013

Monthly Performance Report For September 2013 * All Financial Data is preliminary and unaudited * November 8, 2013 Table of Contents Page # A. Financial Results 1. Summary Performance Report versus Budget Executive Summary A-1.1 Operating Results – YTD A-1.3 Capital Spend Summary – YTD A-1.4 2. Metrics Metrics A-2.1 3. Ridership and Revenue Ticket Revenue and Ridership Summary A-3.1 Ridership and Ticket Revenue by Route Current Month A-3.4 Year to Date A-3.5 Ridership and Revenue - Sleeper Class A-3.6 4. Actual and Forecast Results Income Statement by Business Lines Month, YTD & Forecast vs. Budget and Prior Year A-4.1 Capital Project Overview Regular Projects A-4.6 Mechanical Production Report A-4.8 Engineering Production Report A-4.10 5. Actual Analysis to Prior Year Consolidated Income Statement A-5.1 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows A-5.4 Balance Sheet A-5.5 B. Legislative Report Legislative Updates B-1 C. Route Performance Report – Fully Allocated Summary YTD Route Results C-1 D. Workforce Statistics Headcount Data D-1 Other Employee Costs D-3 E. Performance Indicators Delay Minutes Summary Report E-1 Host Railroad Delay Minutes Report E-2 On-Time Performance E-7 i IINNAANNCCIIAALL EESSUULLTTSS Performance Summary for the Year to Date Period Ending September 2013 Executive Summary: The preliminary and unaudited results for September year to date are favorable to the budget due to lower benefits, train operations and materials. Reimbursable revenues are substantially favorable, but they are offset by increased Reimbursable expenses. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS January 22, 1985 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS a TRIBUTE to the IMMACU the Modern Edifice, Which Occupies the Permanent Church

830 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS January 22, 1985 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A TRIBUTE TO THE IMMACU The modern edifice, which occupies the permanent church. In this Golden Jubliee LATE CONCEPTION CHURCH southeast corner of 44th and California Year of Immaculate Conception B.V.M. ON THEIR lOOTH ANNIVERSA Ave., was designed by the architectural firm Parish the dream of the courageous pio RY of Belli & Belli. According to "The New neers will become a reality as old and young World" the theme of the ch., from the cir will enter the new church to give thanks to cular baptistry in front, to the graceful God for His many and great blessings. HON. WILLIAM 0. LIPINSKI sweep of the nave towards the main altar is A HISTORY OF OUR PARISH-1964 TO 1984 to emphasize the Liturgy, and the public OF ILLINOIS Within the Church there have been IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES and social nature of the Mass. The national parish of I.C. now includes changes. The Liturgy has changed. Mass is Tuesday, January 22, 1985 second and third generation Lithuanians as now celebrated in the language of the well as several hundred Lithuanian families people. The laity now takes a more active e Mr. LIPINSKI. Mr. Speaker, it is part in the celebration of the Mass; we are with great pride that I call attention who came to Chicago from Germany in 1949 and 1950. Families of Polish, Irish, Italian, no longer spectators, we are participants. to a significant event which just German, Mexican, Slovak, English, French, The sacraments have been altered to allow passed in Illinois' Fifth Congressional and Bohemian descent also belong to the us a fuller understanding of them as well a District, which I am privileged to rep congregation.