Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Policy— Unfinished Business

37th Annual Spring Symposium and State-Local Tax Program Tax Policy— Unfinished Business Tangle of Taxes Health Policy Tax Policy and Retirement Issues in Corporate Taxation Tax Compliance Thoughts for the New Congress The Role of Federal and State Federal Impact on State Spending May 17–18, 2007 Holiday Inn Capitol Washington DC REGISTRATION — Columbia Foyer President Thursday, May 17, 8:00 AM - 4:00 PM Robert Tannenwald Friday, May 18, 8:00 AM - 12:30 PM Program Chair All sessions will meet in the COLUMBIA BALLROOM Thomas Woodward Executive Director J. Fred Giertz Thursday, May 17 8:45–9:00 AM WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION 9:00–10:30 AM ROUNDTABLE: RICHARD MUSGRAVE REMEMBERED Organizer: Diane Lim Rogers, Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives Moderator: Henry Aaron, The Brookings Institution Discussants: Helen Ladd, Duke University; Wallace Oates, University of Maryland ; Joel Slemrod, University of Michigan 10:30–10:45 AM BREAK 10:45–12:15 PM TANGLES OF TAXES: PROBLEMS IN THE TAX CODE Organizer/Moderator: Roberton Williams Jr., Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Alex Brill, American Enterprise Institute — The Individual Income Tax After 2010: Post-Permanencism Ellen Harrison, Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP — Estate Planning Under the Bush Tax Cuts Leonard Burman, William Gale, Gregory Leiserson, and Jeffery Rohaly, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center — The AMT: What’s Wrong and How to Fix It Discussants: Roberta Mann, Widener University School of Law; David Weiner, Congressional Budget Office 12:30–1:45 PM LUNCHEON - DISCOVERY BALLROOM Speaker: Peter Orszag, Director, Congressional Budget Office Presentation of Davie-Davis Award for Public Service 2:00–3:30 PM HEALTH POLICY: THE ROLE FOR TAXES Organizer: Timothy Dowd, Joint Committee on Taxation Moderator: Alexandra Minicozzi, Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. -

Brief of Amici Curiae Bipartisan Economic Scholars

No. 19-840 In the Supreme Court of the United States _________ CALIFORNIA, ET AL., Petitioners, v. TEXAS, ET AL., Respondents. _________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit _________ BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR BIPARTISAN ECONOMIC SCHOLARS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS _________ SHANNA H. RIFKIN MATTHEW S. HELLMAN JENNER & BLOCK LLP Counsel of Record 353 N. Clark Street JENNER & BLOCK LLP Chicago, IL 60654 1099 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 (202) 639-6000 May 13, 2020 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .................................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 3 ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 5 I. The Fifth Circuit’s Severability Analysis Lacks Any Economic Foundation And Would Cause Egregious Harm To Those Currently Enrolled In Medicaid And Private Individual Market Insurance As Well As Health Care Providers. ....................................................................... 5 A. Economic Data Establish That The ACA Markets Can Operate Without The Mandate. ................................................................... 5 B. There Is No Economic Reason Why Congress Would Have Wanted The Myriad Other Provisions In The ACA To Be Invalidated. ....................................................... 10 II. Because The ACA Can Operate Effectively Without -

HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy Strategy Paper JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H

THE HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy STRATEGY PAPER JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H. Summers, and Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by making economic growth broad-based, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy—strikingly different from the theories driving economic policy in recent years—calls for fiscal discipline and for increased public investment in key growth- enhancing areas. The Project will put forward innovative policy ideas from leading economic thinkers throughout the United States—ideas based on experience and evidence, not ideology and doctrine—to introduce new, sometimes controversial, policy options into the national debate with the goal of improving our country’s economic policy. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT Printed on recycled paper. THE HAMILTON PROJECT Achieving Progressive Tax Reform in an Increasingly Global Economy Jason Furman Lawrence H. Summers Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution JUNE 2007 The views expressed in this strategy paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of The Hamilton Project Advisory Council or the trustees, officers, or staff members of the Brookings Institution. -

Tax Stimulus Options in the Aftermath of the Terrorist Attack

TAX STIMULUS OPTIONS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE TERRORIST ATTACK By William Gale, Peter Orszag, and Gene Sperling William Gale is the Joseph A. Pechman Senior outlook thus suggests the need for policies that Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institu- stimulate the economy in the short run. The budget tion. Peter Orszag is Senior Fellow in Economic outlook suggests that the long-run revenue impact Studies at the Brookings Institution. Gene Sperling is of stimulus policies should be limited, so as to avoid Visiting Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings exacerbating the nation’s long-term fiscal challen- Institution, and served as chief economic adviser to ges, which would raise interest rates and undermine President Clinton. The authors thank Henry Aaron, the effectiveness of the stimulus. Michael Armacost, Alan Auerbach, Leonard Burman, In short, say the authors, the most effective Christopher Carroll, Robert Cumby, Al Davis, Eric stimulus package would be temporary and maxi- Engen, Joel Friedman, Jane Gravelle, Robert mize its “bang for the buck.” It would direct the Greenstein, Richard Kogan, Iris Lav, Alice Rivlin, Joel largest share of its tax cuts toward spurring new Slemrod, and Jonathan Talisman for helpful discus- economic activity, and it would minimize long-term sions. The opinions expressed represent those of the revenue losses. This reasoning suggests five prin- authors and should not be attributed to the staff, of- ciples for designing the most effective tax stimulus ficers, or trustees of the Brookings Institution. package: (1) Allow only temporary, not permanent, In the aftermath of the recent terrorist attacks, the items. -

Notes for Tax Policy Course

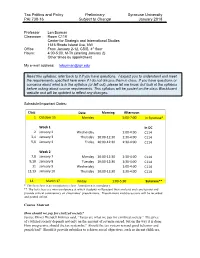

Tax Politics and Policy Preliminary Syracuse University PAI 730-16 Subject to Change January 2018 Professor Len Burman Classroom Room C119 Center for Strategic and International Studies 1616 Rhode Island Ave, NW Office From January 2-12, CSIS, 4th floor Hours: 4:00-5:00, M-Th (starting January 2) Other times by appointment My e-mail address: [email protected] Read this syllabus; refer back to it if you have questions. I expect you to understand and meet the requirements specified here even if I do not discuss them in class. If you have questions or concerns about what is in the syllabus (or left out), please let me know, but look at the syllabus before asking about course requirements. This syllabus will be posted on the class Blackboard website and will be updated to reflect any changes. Schedule/Important Dates: Class Date Morning Afternoon 1 October 15 Monday 5:00-7:00 In Syracuse* Week 1 In DC 2 January 2 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 3,4 January 3 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 5,6 January 4 Friday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 Week 2 7,8 January 7 Monday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 9,10 January 8 Tuesday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 11 January 9 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 12,13 January 10 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 14 March 1? Friday 1:00-5:30 Syracuse** * The first class is an introductory class. -

The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2007 Annual Report

Cover-TPC-2007.indd 1 23.12.2007 21:00:23 The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2007 Annual Report The Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20037 The Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org LETTER FROM THE DIRECTORS When we wrote our first proposals for the Tax Policy Center, we felt the compelling need for timely, high-quality, and comprehensible analysis of tax issues. Fortunately, we were able to convince a small group of generous foundations and individuals, but all of us— funders and researchers alike—wondered if the public would agree. It did. In five years, the Tax Policy Center has become an authority on tax issues. Hardly a day goes by when we’re not called by reporters, policy staffers (and sometimes policymakers themselves), or researchers at other think tanks or universities with tax policy questions. And with an enormous quantity of estimates and analysis on our web site, many others are able to find what they need by themselves. One indication that we’d arrived came in September when Senator Obama’s campaign asked if the Tax Policy Center would host a major speech on tax policy. This request by a major presidential candidate acknowledged our preeminence in taxes and validated everything we’d worked so hard to accomplish. (Of course, TPC is politically neutral and welcomes any major candidate who wishes to address our nation’s tax policy challenges.) From the beginning, we have worked hard to produce timely analysis of tax policy topics. -

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale March 2019 Contact Information Address Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Telephone (202) 797-6148 Fax (202) 797-6181 E-mail [email protected] Current Positions at Brookings 2007- Director, Retirement Security Project 2002- Co-Director and Co-Founder, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2001- Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy 1994- Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Program Prior Employment 1992-present Brookings Institution 2006-2009 Vice President and Director, Economic Studies Program 2001-2006 Deputy Director, Economic Studies Program 1994-2001 Senior Fellow and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1992-1994 Research Associate and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1991-1992 Council of Economic Advisers, Senior Economist 1987-1991 UCLA, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Education 1982-1987 Ph. D., Economics, Stanford University 1977-1981 A. B., Economics, Duke University. Magna Cum Laude 1979-1980 General Course Student, London School of Economics Professional Appointments and Honors (current, except where noted) 2018 Member, Advisory Board, EconoFact 2018 Second Vice President, National Tax Association 2017 Consultant to MSL Group 2017 Panelist, Center for Strategic Development, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Economic Reforms Workshop 2017 2017 Ellen Bellet Goldberg Tax Policy Lecture, University of Florida 2016 Member, Macroeconomic Advisers Board of Advisors 1 2016 2016 Referee of the Year, National Tax Journal 2014-16 Commissioner, Retirement Security and Personal Savings Commission, Bipartisan Policy Center 2013-15 Consultant to Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw LLP 2011-12 Chair, Davie-Davies Committee, National Tax Association 2010-14 Member, Global Agenda Council on Fiscal Crises, World Economic Forum 2009-11 Co-Editor, The Economists’ Voice 2009 Chair, Spring Symposium, National Tax Association 2007 TIAA-CREF Paul A. -

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale April 2015 Contact Information Address Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Telephone (202) 797-6148 Fax (202) 797-6181 E-mail [email protected] Current Positions at Brookings 2007- Director, Retirement Security Project 2002- Co-Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2001- Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy 1994- Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Program Prior Employment 1992-present Brookings Institution 2006-2009 Vice President and Director, Economic Studies Program 2001-2006 Deputy Director, Economic Studies Program 1994-2001 Senior Fellow and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1992-1994 Research Associate and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1991-1992 Council of Economic Advisers, Senior Economist 1987-1991 UCLA, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Education 1982-1987 Ph. D., Economics, Stanford University 1977-1981 A. B., Economics, Duke University. Magna Cum Laude 1979-1980 General Course Student, London School of Economics Professional Appointments (current, except where noted) 2014- Commissioner, Retirement Security and Personal Savings Commission, Bipartisan Policy Center 2013- Consultant to Mayer Brown 2011-12 Chair, Davie-Davies Committee, National Tax Association 2010- Member, Global Agenda Council on Fiscal Crises, World Economic Forum 1 2009-11 Co-Editor, The Economists’ Voice 2009 Chair, Spring Symposium, National Tax Association 2007 TIAA-CREF Paul A. Samuelson Award Certificate of Excellence 2005-6 Consultant to Enterprise Rent-A-Car 2004-6 Consultant to Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw LLP 2004- Board of Directors, Center on Federal Financial Institutions 2004 Adviser, Tax Reform Project, Committee for Economic Development 2003- Research Advisory Council, SEED 2002 Advisory Panel on Dynamic Scoring, Joint Committee on Taxation. -

2005 Annual Report

The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2005 Annual Report Independent, timely, and accessible analyses of current and emerging tax policy issues The Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, NW, Washington, DC 20037 The Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org CONTENTS OVERVIEW................................................................................................... 2 2005 HIGHLIGHTS ...................................................................................... 3 NEW PROGRAM ON STATE AND LOCAL TAXATION ....................... 5 MODEL ENHANCEMENTS........................................................................ 5 OUTREACH .................................................................................................. 6 FUNDRAISING............................................................................................. 8 KEY TPC PERSONNEL.............................................................................. 9 PUBLICATIONS, REPORTS, AND COMMENTARIES ....................... 14 TESTIMONIES ........................................................................................... 19 PUBLIC FORUMS...................................................................................... 20 REVENUE AND DISTRIBUTION TABLES............................................ 20 MEDIA PLACEMENT ................................................................................ 20 1 The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2005 Annual Report OVERVIEW The Urban Institute–Brookings -

Law, Politics, and the Media LAW 839/PSC 700/NEW 500 Wednesday, 2:30P.M.-5:15P.M

Law, Politics, and the Media LAW 839/PSC 700/NEW 500 Wednesday, 2:30p.m.-5:15p.m. Room 204 Syracuse University College of Law Spring 2012 Faculty Keith J. Bybee Lisa A. Dolak Roy S. Gutterman 321 Eggers Hall 244F White Hall Newhouse III, Rm 426 Law and Maxwell Law Newhouse Tully Center Office Hours: Office Hours: Office Hours: Wednesday 10:00-12:00 Monday 12:00-2:00 Monday 10:00-12:00 (and by appointment) (and by appointment) Thursday 10:00-12:00 443-9743 (w) 443-9581 (w) (and by appointment) [email protected] [email protected] 443-3523 (w) 908-337-4534 (cell) [email protected] Graduate Assistant Nicholas Everett Law [email protected] Course Description The American judicial system today operates in a complex environment of legal principle, political pressure, and media coverage. The separate elements of this complex environment are typically studied by different groups of individuals working from different perspectives. Law faculty tend to focus on legal principle; political scientists examine the influence of politics; and scholars of public communication assess the media. The goal of this course is to introduce students to the court system and its environment as a single, integrated subject of study. To this end, the course is taught by a team of faculty instructors drawn from law, journalism, and political science. Academic discussions are complemented by lectures from prominent practitioners from the bench, the bar, the media, and the world of policymaking. Topics to be covered in the course include: public perceptions of the courts; the politics of judicial selection; the relationship between democracy and media; judicial legitimacy; the dynamics of political reporting; the constitutional limits of media coverage; judicial recusals; law and popular culture; courts and the politics of healthcare reform; Wiki-Leaks and confidential information; whistleblowers and good government; taxes and the limits of the policymaking process. -

A UNIVERSAL EITC: SHARING the GAINS from ECONOMIC GROWTH, ENCOURAGING WORK, and SUPPORTING FAMILIES Leonard E

A UNIVERSAL EITC: SHARING THE GAINS FROM ECONOMIC GROWTH, ENCOURAGING WORK, AND SUPPORTING FAMILIES Leonard E. Burman May 20, 2019 ABSTRACT This report analyzes a straightforward mechanism to mitigate middle-class wage stagnation: a wage tax credit of 100 percent of earnings up to a maximum credit of $10,000, called a universal earned income tax credit. The child tax credit would increase from $2,000 to $2,500 and be made fully refundable. A broad-based, value- added tax of 11 percent would finance the new credit. The proposal is highly progressive and would nearly end poverty for families headed by a full-time worker. This report compares the proposal with current law, analyzes its economic effects, compares it to alternative reform options, and considers some complementary policy options. ABOUT THE TAX POLICY CENTER The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center aims to provide independent analyses of current and longer-term tax issues and to communicate its analyses to the public and to policymakers in a timely and accessible manner. The Center combines top national experts in tax, expenditure, budget policy, and microsimulation modeling to concentrate on overarching areas of tax policy that are critical to future debate. Copyright © 2019. Tax Policy Center. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban- Brookings Tax Policy Center. TAX POLICY CENTER | URBAN INSTITUTE & BR OOKINGS INSTITUTION ii CONTENTS ABSTRACT II CONTENTS III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IV INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1 MOTIVATION 4 Economic Inequality -

An IRS-TPC Research Conference Bios of Session Participants

Tax Administration at the Centennial: An IRS-TPC Research Conference Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, N.W., Washington, DC • June 20, 2013 Bios of Session Participants 9:15 – 10:45 Session 1: Individual Income Tax Dynamics Elaine Maag is a Senior Research Associate at the Urban Institute / Tax Policy Center. Her most recent work focuses on understanding the interactions of state and federal income tax systems for low-income families. She has published several articles relating to the simplification of the federal income tax system, particularly with respect to low- and middle-income families as well as articles on tax benefits for families with children. Ms. Maag co-directs the Urban Institute’s Net Income Calculator project which focuses on understanding the interactions of state tax and transfer systems. Prior to joining the Urban Institute, Ms. Maag was a Presidential Management Fellow at the Internal Revenue Service and the General Accountability Office. Leonard Burman is the Director of the Tax Policy Center, a Professor of Public Administration and International Affairs at the Maxwell School of Syracuse University, and research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research and senior research associate at Syracuse University’s Center for Policy Research. He co-founded the Tax Policy Center, a joint project of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution, in 2002. He has held high-level positions in both the executive and legislative branches, serving as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Tax Analysis at the Treasury from 1998 to 2000, and as Senior Analyst at the Congressional Budget Office. He is past-president of the National Tax Association.